Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

3 Theories, Approaches, and Frameworks in Community Work

Sama Bassidj, MSW, RSW and Dr. Mahbub Hasan MSW, Ph.D.

- Why Is Theory Important in Community Work?

- Systems Theory

- Anti-Oppressive Practice

- Cultural Humility and Cultural Safety

- Indigenous Worldviews

Introduction

This chapter focuses on theories and why theories are required in community development practice. There are many theories in social work; however, we will discuss four main theories that community workers should integrate into their practice. These theories are Systems Theory, Anti-Oppressive Practice, Cultural Humility and Safety, and Indigenous Worldviews.

1. Why Is Theory Important in Community Work?

Theories help us make sense of the world – and communities – around us. They allow us to explore problems and solutions with evidence and research to support our practice, instead of grasping at straws. This is particularly important as community workers need to be aware of personal assumptions and biases that may interfere with effective community practice.

Theories may also help us avoid doing harm , unintentionally . Good intentions are not enough for community development work. As social service professionals, it is critical for us to be aware of the ways that our work can perpetuate harm and oppression – and intentionally take steps to disrupt harmful systems and practices today. In order for us to avoid repeating harmful mistakes of the past, community work must be grounded in anti-oppressive, anti-racist, and decolonizing practices and relations.

In order for us to explore different theoretical frameworks for working with communities, we must first understand what exactly we mean by community . At the most fundamental level, a community is based on relationships, identity, and a sense of belonging.

How can theories support our practice with diverse communities? What can they offer to community development work?

We will be introducing the following theoretical frameworks for community work:

- Cultural Humility and Safety

- Anti Racism

Note: Keep in mind that this is not an exhaustive list. Continually evolving our practice, drawing on multiple theories from our toolbox, allows for deeper and broader understanding and engagement with diverse communities.

2. Systems Theory

Like every ecosystem , individuals require ongoing input (e.g. food, energy, relationships) in order to survive – and hopefully thrive. When a system’s needs are not met, we may feel out of balance, which prompts action. Preserving a state of balance (or equilibrium ) is critical for systems to survive.

According to systems theory (Healy, 2005) :

- Individuals do not live in silos (or isolation).

- We are constantly interacting with multiple systems (e.g. family, neighbourhood, city, globe) across different levels.

- Our interactions, whether big or small, have an inevitable ripple effect throughout the entire system.

- All systems operate in relationships with other systems.

This perspective allows us to develop a holistic view of individuals and communities in our practice.

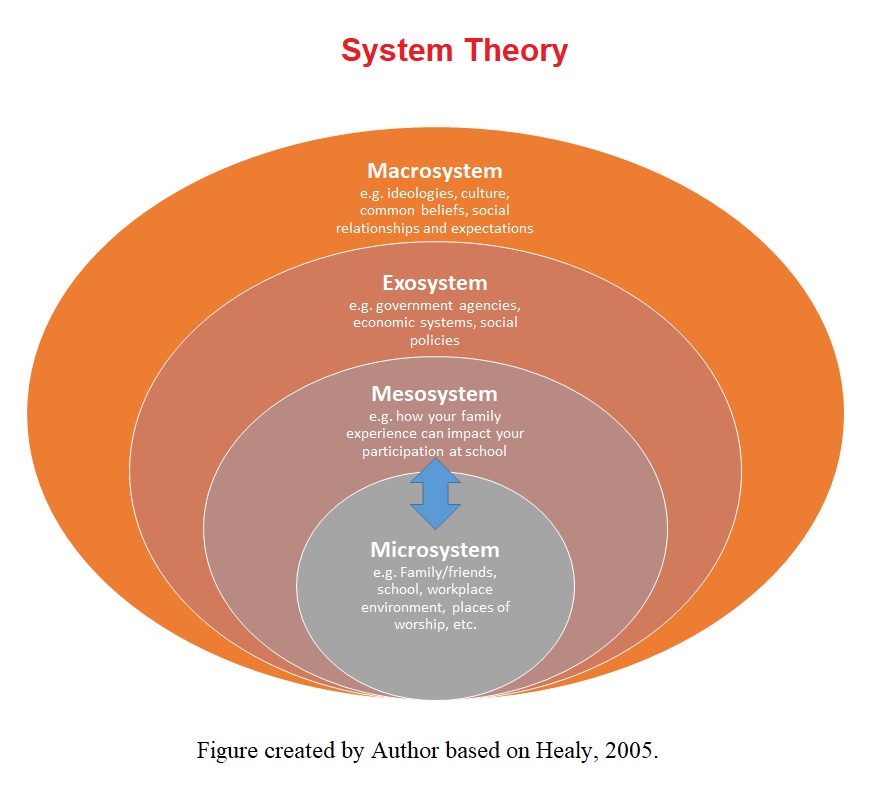

Healy (2005) suggests that in addition to your self as the primary system, reflect on some of the following systems you interact with (from smallest to largest):

- Microsystem – the small immediate systems in your day-to-day life (e.g. family/friends, workplace environment, classrooms, places of worship, etc.)

- Mesosystem – the network of interactions between your immediate systems (e.g. how your family experience can impact your participation at school)

- Exosystem – the larger institutions in society that impact your personal systems and networks (e.g. government agencies, economic systems, social policies, etc.)

- Macrosystem – the intangible influences in society (e.g. ideologies, culture, common beliefs, social relationships and expectations, etc.)

3. Anti-Oppressive Practice

Q – What is the difference between more mainstream approaches and anti-oppressive practice (AOP)? How does AOP help communities understand problems as linked to social inequality?

Part of this section is adapted from: Canadian Settlement in Action: History and Future by NorQuest College is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Oppression can be defined as the experience of widespread, systemic injustice (Deutch, 2011). It is embedded in the underlying assumptions of institutions and rules, and the collective consequences of following those rules. Oppression is often a consequence of unconscious assumptions and biases and the reactions of well-meaning people in ordinary interactions (Khan, 2018).

The following are some of the ways oppression can manifest itself:

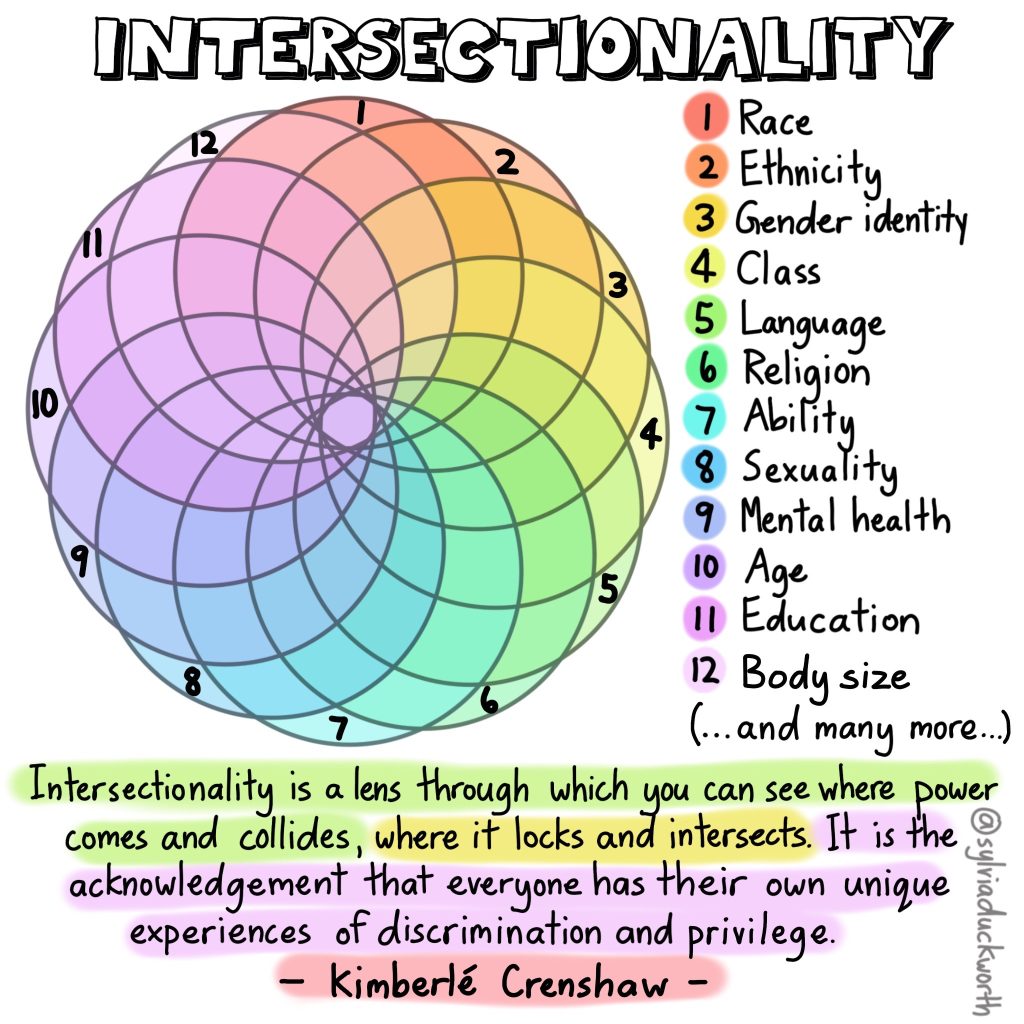

Intersectionality Venn diagram by SylviaDuckworth is licensed under a CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 Generic license

Intersectionality is a core concept in the discussion of oppression. Crenshaw (1989) pioneered the term “ intersectionality ” to refer to instances in which individuals simultaneously experience many intersecting forms of oppression. Since individuals don’t exist solely as “woman”, “Black”, or “working class”, among others, these identities intersect in complex ways, and are determined by a set of interlocked social hierarchies.

Video: The urgency of intersectionality | Kimberlé Crenshaw. Ted Talk.

Source: YouTube. https://youtu.be/akOe5-UsQ2o

Therefore, all our oppressions are interconnected and overlapping . Intersectionality rejects the idea of “ranking” social struggles (sometimes referred to as “ Oppression Olympics ”), as this is divisive and unnecessary, undermining solidarity (the willingness of different individuals or communities to work together to achieve common goals).

In an intersectional analysis, a person’s identity is layered, and the presence (or absence) of oppression is context-specific. The same person could feasibly be oppressed in one situation, and the oppressor in another (for example, a Black man who experiences racism in the workplace but is domestically abusive). What is important is to look at the social forces that are at play and to remember that “the personal is always political”.

It would be difficult to discuss the importance of understanding oppression without understanding privilege . Garcia (2018) describes privilege as unearned social benefits or advantages that a person receives by virtue of who they are, not what they have done. Much like oppression, privilege can also be intersectional; however, because privilege is unearned, it is often invisible because those who benefit from it have been conditioned to not even be aware of its existence. Privilege is thus a very important concept because the relationship that community workers have with communities is often a privileged standing, as they have power over the lives of the communities they work with.

Video: What is Privilege ? Source: YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hD5f8GuNuGQ&feature=youtu.be

Among the most important roles that can be played by a community worker is that of an ally – when a person with privilege attempts to work and live in solidarity with marginalized peoples and communities. Allies take responsibility for their own education on the lived realities of oppressed individuals and communities and are willing to openly acknowledge and discuss their privileges and the biases they produce (Lamont, n.d.).

A thorough understanding of power, privilege, and oppression can help community workers develop an anti-oppressive approach to their practice. Being able to engage in anti-oppressive practice requires community workers to be able to deconstruct and challenge the Great Canadian Myth and expressions of Canadian exceptionalism , and to be able to discuss the often-complicated role played by social service professionals in the perpetuation and execution of harmful government policies towards racialized communities (Clarke, 2016, p. 119). As such, an anti-oppressive approach requires community workers to continually and critically reflect on their work with communities and to challenge the status of “expert” assigned to them.

Anti-oppressive practice is also a strengths-based approach in that the starting point of a conversation with communities is what they can do, not what they cannot do or are lacking . Strengths-based approaches separate people from their problems and focus more on the circumstances that prevent a person from leading the life they want to lead (Hammond & Zimmerman, 2012, p. 3).

Anti oppression approach addresses the prejudicial and inequitable relations that communities experience (Parada et al. 2011). Anti-oppressive social workers and community workers help communities understand that their problems are linked to social inequality and why they are oppressed and how to fight for change (Baines, 2011). Anti oppression practice addresses root causes of poverty and marginalization and promote collective actions by community.

4. Anti-Racism

Anti-racism is the active process of identifying and eliminating racism by changing systems, organizational structures, policies and practices and attitudes, so that power is redistributed and shared equitably” (attributed to NAC International Perspectives: Women and Global Solidarity- Source: Calgary Anti-Racism Education ).

In an academic context, anti-racism represents a proactive ideological orientation and mode of engagement aimed at reshaping the societal and community landscape. Given the pervasive nature of racism across various strata and domains of society, it (racism) serves as a mechanism for establishing and perpetuating exclusive hierarchies and domains. Consequently, the imperative for anti-racism education and activism extends comprehensively across all facets of society, rather than being confined solely to the workplace, educational institutions, or specific sectors of individual existence. According to Calgary Anti-Racism Education , Anti-racism theory analyzes/critiques racism and how it operates, which provides us with a basis for taking action to dismantle and eliminate it (Henry & Tator, 2006; Kivel, 1996). Ontario Anti-Racism Secretariat defines Anti-racism is the practice of identifying, challenging, and changing the values, structures and behaviours that perpetuate systemic racism” (Source: Calgary Anti-Racism Education ).

5. Cultural Humility and Cultural Safety

Material in this section is adapted from Introduction to Human Services by Nghi D. Thai and Ashlee Lien is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

5.1 Cultural humility is the ability to remain open to learning about other cultures while acknowledging one’s own lack of competence and recognizing power dynamics that impact the relationship.

Within cultural humility it is important to:

- engage in continuous and critical self-reflection

- recognize the impact of power dynamics on individuals and communities

- embrace a perspective of “not knowing”

- commit to lifelong learning

This approach to diversity encourages a curious spirit and the ability to openly engage with others in the process of learning about a different culture. As a result, it is important to address power imbalances and develop meaningful relationships with community members in order to create positive change. A guide to cultural humility is offered by Culturally Connected.

Video: Cultural Humility, Source: YouTube, https://youtu.be/SaSHLbS1V4w

5.2 Cultural Safety

Culturally unsafe practices involve any actions that diminish, demean, or disempower the cultural identity and well-being of an individual.

According to Population Health Promotion and BC Women’s Hospital :

Culturally unsafe practices involve any actions that diminish, demean, or disempower the cultural identity and well-being of an individual. Creating a culturally safe practice involves working to create a safe space that is sensitive and responsive to a client’s social, political, linguistic, economic, and spiritual realities. Ultimately, adopting a cultural humility perspective is one of the most effective ways to enable cultural safety – one that will help clients feel safe receiving and accessing care.

Indigenous Cultural Safety and Cultural Humility

As a result of Canada’s legacy of colonization with Indigenous Peoples, working towards cultural safety and trust requires humility, dedication, and respectful engagement. Indigenous Cultural Safety is when Indigenous Peoples feel safer in relationships and communities.

According to BC Patient Safety and Quality Council , working towards culturally safe engagement with Indigenous communities requires:

- Acknowledgement of the history of colonialism in Canada and the impacts of systemic racism.

- A level of cultural awareness and sensitivity . (e.g. Provide a meaningful land acknowledgement. Get to know Indigenous Peoples from the Land you work and live on. Be a lifelong learner. )

- Deep humility and an openness to learning . (e.g. Research local cultural practices and protocols. Read the Truth and Reconciliation Recommendations. )

- Time for relationship building, connection , collaboration, and cultivating trust . ( e.g. Work towards balancing power dynamics. Be mindful of experiences of intergenerational trauma in building relationships. Integrate trauma-informed community practices . )

According to San’yas Anti-Racism Indigenous Cultural Safety Training Program a commitment to Indigenous Cultural Safety recognizes that:

- cultural humility aims to build mutual trust and respect and enables cultural safety

- cultural safety is defined by each individual’s unique experience and social location

- cultural safety must be understood, embraced, and practiced at all levels of community practice

- working towards cultural safety is everyone’s responsibility

6. Indigenous Worldviews

Community development practice owes much of its ways of knowing, doing, and being to Indigenous communities worldwide. Indigenous values of interdependence and caring for all are at the heart of this practice.

According to activist and academic Jim Silver (2006), who is non-Indigenous:

The process of people’s healing, of their rebuilding or recreating themselves, is rooted in a revived sense of community and a revitalization of [Indigenous] cultures…The process of reclaiming an [Indigenous] identity takes place, therefore, at an individual, community, organizational, and ultimately political level. This is a process of decolonization that, if it can continue to be rooted in traditional [Indigenous] values of sharing and community, will be the foundation upon which healing and rebuilding are based. (p. 133)

Many Indigenous authors acknowledge one’s identity as intricately connected to community (Carriere, 2008). In fact, family, kinship, and community are viewed as a significant determinant of well-being (Kral, 2003). This community identity is often place-based , connected to the Land and one’s place of origin.

Baskin (2016) shares an example of an Indigenous community program that emphasizes the well-being of the community and family above that of the individual:

[At] Mino-Yaa-Daa (meaning “Healing Together” in the Anishnawbe language), [t]he individual is seen in the context of the family, which is seen in the context of the community… when an individual is harmed, it is believed that this affects all other individuals in that person’s family and community… By coming together in a circle, women learned that they were not alone, and that their situations and feelings were similar to those of other women… [building relationships and a community of empowered women] can only be achieved by individuals coming together in a circle. This kind of community-building cannot happen through individual counselling or therapy (pp. 164-165).

Key Takeaways and Feedback

We want to learn your key takeaways and feedback on this chapter.

Your participation is highly appreciated. It will help us to enhance the quality of Community Development Practice and connect with you to offer support. To write your feedback, please click on Your Feedback Matters .

Baines, D. Ed. (2011). Doing anti-oppressive practice: Social justice social work. Halifax: Fernwood Press.

Baines, D. (2017). Doing anti-oppressive practice: Social justice social work (Third ed.). Fernwood Publishing.

Baskin, C. (2016). Strong helpers’ teachings: The value of Indigenous knowledges in the helping professions (Second ed.). Canadian Scholars’ Press.

Bergland, C. (2017, August 3). Sizeism is harming too many of us: Fat shaming must stop. Psychology Today . https://www.psychologytoday.com/ca/blog/the-athletes-way/201708/sizeism-is-harming-too-many-us-fat-shaming-must-stop

Carriere, J. (2008). Maintaining identities: The soul work of adoption and Aboriginal children. Pimatisiwin: A Journal of Aboriginal and Indigenous Community Health, 6 (1), 61-80. Retrieved from http://www.pimatisiwin.com .

Clarke, J. (2016). Doing anti-oppressive settlement work in Canada: A critical framework for practice. In S. Pashang (Ed.), Unsettled settlers: Barriers to integration (3rd ed., pp. 115–137). de Sitter Publications.

Class Action. (2021). What is classism. https://classism.org/about-class/what-is-classism/

Crenshaw, K. (1989). Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics, University of Chicago Legal Forum , ( 1 , 8). http://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/uclf/vol1989/iss1/8

Deutsch, M. (2011). A framework for thinking about oppression and its change. Social Justice Research, 19 (1), 193–226.

Eisenmenger, A. (2019, December 12). Ableism 101: What it is, what it looks like, and what we can do to fix it. Access Living. https://www.accessliving.org/newsroom/blog/ableism-101/

Healy, K. (2005). Under reconstruction: Renewing critical social work practices. In S. Hick, J. Fook, & R. Pozzuto (Eds.), Social work: A Critical turn (pp. 219-230). Toronto: Thompson Educational.

Garcia, J. D. (2018). Privilege (Social inequality) . Salem Press Encyclopedia . https://guides.rider.edu/privilege

Illing, S. (2020, March 7). What we get wrong about misogyny. Vox. https://www.vox.com/identities/2017/12/5/16705284/elizabeth-warren-loss-2020-sexism-misogyny-kate-manne

Khan, C. (2018). Social location, positionality & unconscious bias [PowerPoint presentation]. University of Alberta Graduate Teaching and Learning Program. https://www.ualberta.ca/graduate-studies/media-library/professional-development/gtl-program/gtl-week-august-2018/2018-08-28-social-location-and-unconscious-bias-in-the-classroom.pdf

Kral, M.J. (2003). Unikaartuit: Meanings of well-being, sadness, suicide and change in two Inuit communities. Final report to the National Health Research and Development.

Lamont, A. (n.d.). Guide to allyship . amélie.studio. https://guidetoallyship.com/

Ontario Human Rights Commission. (n.d.a). Ageism and age discrimination (fact sheet). http://www.ohrc.on.ca/en/ageism-and-age-discrimination-fact-sheet

Ontario Human Rights Commission. (n.d.b). Racial discrimination, race and racism (fact sheet). http://www.ohrc.on.ca/en/racial-discrimination-race-and-racism-fact-sheet

Parada, H, Barnoff L, Moffatt K, & Homan, S. (2011). Promoting community change: Making it happen in the real world. Toronto: Nelson Education

Planned Parenthood. (2021a). What is homophobia? https://www.plannedparenthood.org/learn/sexual-orientation/sexual-orientation/what-homophobia

Planned Parenthood. (2021b). What is transphobia? https://www.plannedparenthood.org/learn/gender-identity/transgender/whats-transphobia

Silver, J. (2006). In their own voices: Building urban Aboriginal communities. Black Point, NS: Fernwood Publications.

Community Development Practice: From Canadian and Global Perspectives Copyright © 2022 by Mahbub Hasan is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

IMAGES

VIDEO