- Resource Library

- _Beta Reading

- Publications

- _Guest Blog Posts

- _My Writing

- _Writing Tips

- _Writing Life

- _Shelby's Thoughts

- _Recomendations

- __Audiobooks

Social Icons

How to Write a Hermit Crab Essay

Saturday, february 2, 2019 • writing tips.

What is a Hermit Crab Essay?

How to construct a hermit crab essay.

More Inspiration and Examples

You may also like, no comments:, post a comment.

Unpacking the Hermit Crab Essay: A Reading List

Before I began writing personal essays, I was an academic. My training was in classics and history of medicine, two fields that allowed me to assert my intellectual invulnerability while talking about deeply personal topics—sexuality, mental illness, femininity—within the armor of conference papers, journal articles, book reviews, and a monograph. Close readings of ancient medical texts allowed me to explore in subterranean ways my family history of anorexia. Quotations from early Christian preachers functioned like found text through which I could begin to comprehend how ministers in my childhood churches had warped my passageway into adulthood as a queer person. Footnotes gave me room to skip-jump over sources and scholarship, sliding in comic asides and ironic juxtapositions, to spin the reader around and offer a glimpse of connections that went unexamined in the argument itself.

Perhaps because of this history, I find hermit crab essays fascinating. First named as such by Brenda Miller and Suzanne Paola in Tell It Slant , hermit crab essays steal conventionalized forms (such as math tests, prescriptions, rejection letters, syllabi) as “shells” to contain and protect the material within. The form refines the game I played as a scholar: taking a serious, perhaps even pompous, structure and then teasing it out to examine a question about oneself, one’s relationships and take on the world.

Margot Singer, “On Scaffolding, Hermit Crabs, and the Real False Document” (in Bending Genres: Essays on Creative Nonfiction )

Singer situates hermit crabs in the tradition of using fake documentary evidence, such as newspaper reports in novels. Yet, as she argues, hermit crabs contribute something innovative to how we think about creative nonfiction in particuklar, transforming the essay from a linear string of sentences to a structure such as a house or a room (as in the “stanza”) that the writer and reader might inhabit.

What moved me: The hermit crab essay as a house. Any essay as a house. The way it takes time to settle after a move, to become familiar with which floorboards creak, where precisely the light falls in the morning. The way buildings construct sight-lines and passageways, signal or obscure their contents, change as they pass among inhabitants.

Chelsea Biondolillo, On Shells

A t first sight, “On Shells” is a simple braided essay that intertwines memoir of Biondolillo’s grandmother, who had a passion for beach-combing, with reflections on using the hermit crab essay in creative writing classrooms. Yet, it emerges quickly as a hermit crab essay on the craft of hermit crab essays: through fragmentary paragraphs (broken shells), Biondolillo suggests that we can learn something about writing from the practice of beach-combing. Biondolillo communicates her insights through juxtaposition: what the conchologist says about the hermit crab we can, with the author’s encouragement, apply to our own writing practice.

What moved me: Discovering unique, never-before-seen shells is not the point. Instead, stay alert and curious about what washes up on your own shores.

Suzanne Cope, The Essay as Bouquet

Various writers have offered accounts of what it is in particular that hermit crabs do. A good example is Suzanne Cope’s examination of hermit crab essays that take forms connected to the natural world: she finds that few imitate natural forms; instead, hermit crab essays that brush up against “nature” tend to explore the entanglement of wilderness and human interference.

What moved me: Hermit crab essays as the exploration of breakages and imperfection.

Randon Billings Noble, Consider the Platypus: Four Forms—Maybe—of the Lyric Essay

Each form of the lyric essay t hat Noble discusses—flash, fragmentary, braided, and hermit crab—uses structure to explore its central theme. Hermit crab essays, according to Noble, protect what is vulnerable and contain excess; further, they are social creatures, relying on (literary) networks for their construction of meaning.

What moved me: Hermit crab essays as an exercise in connection.

Susan Mack, The Hermit Crab Essay: Forming a Humorous Take on Dark Memoir

Hermit crab essays are associated with vulnerability, and many are about traumatic experiences. Is this a necessary feature? (Biondolillo, in On Shells , reports being asked this question by her students.) The answer is probably not, although they do lend themselves to difficult material. As Mack explores, hermit crabs not only provide protection but also can be enormously funny. Humor thrives in unexpected juxtapositions, which is the daily fare of the hermit crab form.

What moved me: Hermit crab essays as an opportunity to stop taking myself so damn seriously.

Rich Youman, Haibun & the Hermit Crab: “Borrowing” Prose Forms

Juxtaposition is at the heart of Youman’s exploration of the potential of hermit crab essays within the traditional Japanese form known as the haibun, where prose and haiku work together. As Youman shows, the hermit crab’s borrowed form, which is often documentary or official, can heighten the contrast with the haiku.

What moved me: The in-rush of breath as the haiku brings the glimpse of mundane reality to an abrupt and delicate pause.

Brenda Miller, The Shared Space Between Read and Writer: A Case Study

Hermit crab essays are a useful classroom tool for various reasons: constraints loosen creative inhibitions; the form serves as a disguise, which can support self-conscious writers in sharing vulnerable material; the exercise trains writers to pay attention to how texts are constructed. Telling the story of how she wrote her hermit crab essay We Regret to Inform You while teaching, Miller emphasizes how form dictates content, giving the writer room to experiment.

What moved me: Don’t write the essay and then manipulate it into an unusual form for the sake of gimmick. Instead, find a form that intrigues you and let it shape what you are trying to say.

Kim Adrian (ed.), The Shell Game

Adrian’s introduction to this recent anthology of hermit crab essays mimics an entry in a natural history encyclopedia. Hermit crabs, Adrian writes, are part of a tradition of hybrid forms, but they also reflect current interest in challenging inherited categories and binaries. While they sometimes appear to be a kind of party trick, they are, in another light, the very epitome of the essay—the attempt to express the interior self through the clumsy vessel of writing that so often pretends to be about something else.

What moved me: Hermit crab essays as drag. Just as drag offers overt performances of the deconstruction of traditional gender, so too hermit crab essays perform the deconstruction of the essay, which is at its core (just like gender) a set of conventions that simultaneously enable and constrict self-expression. Hermit crabs as a site for playful experimentation concealing sharp literary critique.

Bonus: Ocean Vuong, Seventh Circle of the Earth

For those curious to see how footnotes might contain a narrative, Vuong’s account of the immolation of two gay men in Texas offers a grim and potent example. As Vuong describes in his introduction to this poem, the very space on the page—the absence of text to which footnotes might be appended—is key to its meaning.

What moved me: The space that the footnotes leave behind, the breathlessness in it, the suspension of thought.

About the author

Jessica Wright

Jessica Wright is a historian and writer based in West Yorkshire. Her work has been published in journals such as Michigan Quarterly Review, Queerlings Magazine, Foglifter Journal, and Mslexia. Her first book, The Care of the Brain in Early Christianity , came out with University of California Press in 2022.

The Hermit Crab Essay: Brenda Miller Unshells her Own

by Mark Alvarez

A hermit crab essay is one that imitates a non-literary text—recipe, obituary, rejection letter—using the found form in novel ways, but retaining the semantic resonance of the original. Brenda Miller , who with Suzanne Paola coined the term in 2003, said that one of the benefits of working with these restrictions is creative expansion.

“It lets us get out of our own way,” Miller said at the 2018 Nonfiction Now conference in Phoenix, Arizona. “Following form dictates content, allowing writers to engage their imagination.”

To give an example of how this can occur, Miller discussed the process behind her essay, “ We Regret to Inform You ,” originally published in The Sun .

The essay began as a parody of rejection letters, using their form to write about her own personal experiences. One rejection letter is from to an elementary school artist from her art class; another for “the position of girlfriend of the star of the high-school football team.”

Even in the short space of the panel, Miller trained the audience how to react to her piece. The first two letters were funny, filled with solid jokes. We were laughing—emotion was sounded. When the third letter turned out to be about her miscarriage, there were audible sighs and moans. That reaction would not have occurred if Miller hadn’t first set us up with comic material and invited us to engage physically with her piece through laughter.

The form of the rejection letter allowed Miller to write about such a difficult subject.

“This voice is so detached, I can say whatever I want,” Miller said. “Humor naturally arises when coupling detached voice with intimate experience.”

The tonal shift from the essay’s early light moments to the pathos of the later was unexpected, even for Miller.

“The form of the rejection letter created an entirely new universe where personal narrative doesn’t belong to you,” Miller said. “It creates better meanings than you could yourself.”

“Who am I to question the ferocity of an essay in progress?” Miller said. “Eventually story goes beyond the form. This is exactly what hermit crabs do—outgrow their shell and get another.”

Miller teaches the hermit crab essay so often that her classes at Western Washington University have mastered it. Now she teaches how not to do the traditional hermit crab essay.

“Hermit crab essays have become so normal,” Miller said. To fight this ossification, she offers several tips:

- Inhabit the form with the voice of the form

- Ask yourself why you are using the form

- Think about how to make it not about you, but something bigger

- How do you end the thing? A lot of hermit crab essays just end, stop, without ever reaching something grander or crescendo.

In honor of the last point, I offer you a crappy ending.

But I also offer a much deeper essay by Miller on her process writing “We Regret to Inform You,” published in Brevity .

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

- Craft Essays

- Teaching Resources

The Shared Space Between Reader and Writer: A Case Study

Brenda Miller

I often teach classes on the form of the “hermit crab” essay, a term Suzanne Paola and I used in our textbook Tell It Slant . Hermit crab essays adopt already existing forms as the container for the writing at hand, such as the essay in the form of a “to-do” list, or a field guide, or a recipe. Hermit crabs are creatures born without their own shells to protect them; they need to find empty shells to inhabit (or sometimes not so empty; in the years since I’ve begun using the hermit crab as my metaphor, I’ve learned that they can be quite vicious, evicting the shell’s rightful inhabitant by force).

When I teach the hermit crab essay class, we begin by brainstorming the many different forms that exist for us to plunder for our own purposes. Once we have such a list scribbled on the board, I ask the students to choose one form at random and see what kind of content that form suggests. This is the essential move: allowing form to dictate content. By doing so, we get out of our own way; we bypass what our intellectual minds have already determined as “our story” and instead become open and available to unexpected images, themes and memories. Also, following the dictates of form gives us creative nonfiction writers a chance to practice using our imaginations, filling in details, and playing with the content to see what kind of effects we can create.

I’ve taught the hermit crab class many, many times over the years, in many different venues. So, often it’s tempting for me to sit out the exercise; after all, what else could I possibly learn? But after just a minute, it becomes too boring to watch other people write, so I dive in myself, with no expectation that I’ll write anything “good.” In one class, I glanced at the board we had filled with dozens of forms. And my eye landed on “rejection notes.” So that is where I began:

April 12, 1970

Dear Young Artist:

Thank you for your attempt to draw a tree. We appreciate your efforts, especially the way you sat patiently on the sidewalk, gazing at that tree for an hour before setting pen to paper, the many quick strokes of charcoal executed with enthusiasm. But your drawing looks nothing like a tree. In fact, the smudges look like nothing at all, and your own pleasure and pride in said drawing are not enough to redeem it. We are pleased to offer you remedial training in the arts, but we cannot accept your “drawing” for display.

With regret and best wishes,

The Art Class

Andasol Avenue Elementary School

Well, once one gets on the subject of rejection, you can imagine how the material simply flows through one’s fingertips. And I’m not really thinking about the content at all; I’m engaged in honing the voice of the rejection note, creating a persona on the page that can “speak back” to me, in a humorous way, all that had gone unspoken in real life. I’m having an immensely good time.

Here’s one that comes early on in the essay:

October 13, 1975

Dear 10 th Grader:

Thank you for your application to be a girlfriend to one of the star players on the championship basketball team. As you can imagine, we have received hundreds of similar requests and so cannot possibly respond personally to every one. We regret to inform you that you have not been chosen for one of the coveted positions, but we do invite you to continue hanging around the lockers, acting as if you belong there. This selfless act serves the team members as they practice the art of ignoring lovesick girls.

The Granada Hills Highlanders

P.S: Though your brother is one of the star players, we could not take this familial relationship into account. Sorry to say no! Please do try out for one of the rebound girlfriend positions in the future.

So I’m going along chronologically, calling up (and enhancing, exaggerating, manipulating) all the slights and hurts of an ordinary life. I’m having a marvelous time, because this voice is so detached it can say whatever it wants. I’m submitting to the voice of the essay, allowing the form to lead me where it will go.

And as I follow that voice, the notes begin to demand more room, wanting to break free of the concise form and allow for more in-depth story. Now that I’ve established the voice of the form, I can expand on that voice to create more variety and narrative. I can also broaden the concept of the rejection note in order to create sections that work for the subject matter. For example:

December 10, 1978

Dear College Dropout:

Thank you for the short time you spent with us. We understand that you have decided to terminate your stay, a decision that seems completely reasonable given the circumstances. After all, who knew that the semester you decided to come to UC Berkeley would be so tumultuous: that unsavory business with Jim Jones and his bay area followers, the mass suicide, an event that left us all reeling. After all, who among us has not mistakenly followed the wrong person, come close to swallowing poison?

And then Harvey Milk was shot. A blast reverberating across the bay. It truly did feel like the world was falling apart, we know that. We understand how you took refuge in the music of the Grateful Dead, dancing until you felt yourself leave your body behind, caught up in their brand of enlightenment. But you understand that’s only an illusion, right?

And given that you were a drama major, struggling on a campus well known for histrionics and unrest: well, it’s only understandable that you’d need some time to “find yourself.” You’re really too young to be in such a city on your own. When you had your exit interview with the Dean of Students, you were completely inarticulate about your reasons for leaving, perhaps because you really have no idea. You know there is a boy you might love, living in Santa Cruz. You fed him peanuts at a Dead Show. You imagine playing house with him, growing up there in the shadows of large trees.

But of course you couldn’t say that to the Dean, as he swiveled in his chair, so official in his gray suit. He clasped his hands on the oak desk and waited for you to explain yourself. His office looked out on the quad where you’d heard the Talking Heads playing just a week earlier. And just beyond that, the dorm where the gentleman you know as “pink cloud” provided you with LSD in order to experience more fully the secrets the Dead whispered in your ear. You told the Dean none of this, simply shrugged your shoulders and began to cry. At which point the Dean cleared his throat and wished you luck.

We regret to inform you that it will take quite a while before you grow up, and it will take some cataclysmic events of your own before you really begin to find the role that suits you. In any case, we wish you the best in all your future educational endeavors.

UC Berkeley Registrar

And then, as the years from my past go by, I find that the essay is leading me somewhere I didn’t expect. I actually pause and say to the essay, “we’re really going there?” and the essay says, of course we are! So, I find myself here:

October 26, 1979

Dear Potential Mom,

Thank you for providing a host home for us for the few weeks we stayed in residence. It was lovely but, in the end, didn’t quite work for us. While we tried to be unobtrusive in our exit, the narrowness of your fallopian tubes required some damage. Sorry about that. You were too young to have children anyway, you know that, right? And you know it wasn’t your fault, not really…Still, we enjoyed our brief stay in your body and wish you the best of luck in conceiving children in the future.

With gratitude,

Ira and Isabelle

So, as you can tell, the essay takes a turn there, or maybe “turn” is not the right word; it slows down and peers below the surface. It tells me this is where we were going all along. I’ve written about this material so many times in the past, that I didn’t feel I would ever return to it. But the essay demanded it, and who am I to question the ferocity of an essay in progress?

And this time I feel a kind of transformation happening, a new perspective, a moment of forgiveness. It’s odd to feel this in one’s writing, to feel so concretely that the essay is, indeed, in charge: speaking to you, telling you things you didn’t already know. And this happened solely because of the form. The form of the rejection note—though it began as a technical exercise—created an entirely new universe in which one’s personal narrative does not really belong to you. And because it doesn’t belong to you, it can create meanings—perhaps better meanings—than any you might have thought up on your own.

The essay, now titled “We Regret to Inform You” (what else could it be?), moves, as it must, as life does, quickly through this time period. It has created its own momentum and can’t stop now! The essay has also now provided me with a theme that can echo through the rest of the sections. For example:

June 30, 1999

Dear Applicant:

Thank you for your query about assuming the role of stepmother to two young girls. While we found much to admire in your résumé, we regret to inform you that we have decided not to fund the position this year. You did ask for feedback on your application, so we have the following to suggest:

- You do not yet understand the delicate emotional dynamic that rules a divorced father’s relationship with his children. The children will always, always, come first, trumping any needs you, yourself, may have at the time. You will understand this in a few years, but for now you still require some apprenticeship training.

- Though you have sacrificed time and energy to support this family, it’s become clear that your desire to stepmother stems from some deep-seated wound in yourself, a wound you are trying to heal by using these children. Children are intuitive, though they may not understand what they intuit. They have enough to deal with–an absent mother, a frazzled father–they don’t need your traumas entering the mix.

- Seeing the movie “Stepmom” is not an actual tutorial on step-parenting.

- On Mother’s Day, you should not expect flowers, gifts, or a thank you. You are not their mother.

- You are still a little delusional about the true potential here for a long-term relationship. The father is not yet ready to commit, so soon after the rather messy divorce. (This should have been obvious to you when he refused to hold your hand, citing that it made him “claustrophobic.” Can you not take a hint?)

As we said, funding is the main criteria that led to our rejection of your offer. We hope this feedback is helpful, and we wish you the best in your future parenting endeavors.

Through several revisions of the draft—which included nearly twice as many letters as represented in the final version (as I said, once you get on the subject of rejection, you can really go on and on and on)—I honed the themes I saw rising in the essay through, or perhaps in spite of, the harsh voice of the rejection note. There was the ostensible theme of children or lack thereof, but more insistently there was the theme of how we find the roles one is suited to play in one’s life. So I kept the letters that had echoes of that theme and deleted the rest. I highlighted the theme through key words and phrases to create a fragmented piece that felt coherent and satisfying.

Throughout the process—both drafting and revising—I did not feel the emotional weight of any of the material. In fact, I was laughing most of the time, inordinately pleased with my cleverness. Humor naturally arises when we couple a detached voice with intimate stories, and since audiences are also usually laughing throughout the essay, the weight of that turn in the middle almost has more impact than if I had started with this material as the destination. And we get through it quickly. It’s one moment in a series of moments that accumulate to a greater end.

So, the essay gets published in The Sun, and I receive lots of responses, more than I’ve ever received for any essay in my life. I’ve written about a lot of personal material over the years, but this essay seems to have struck a deeper chord. And I think people are touched by “We Regret to Inform You” not because of the revelation of my personal “rejections,” but because I’ve used a form that invites readers into both my experience and their own. By being ensconced in a more objective form, the essay provides what I’ll call a “shared space” between reader and writer. We often wonder how to make our personal stories universal; well, perhaps it’s not a question of making our stories do anything. Maybe, instead, we simply need to provide common ground in the form of an object we use together. We sit down at the same table and the stories pass between us.

Brenda Miller directs the MFA in Creative Writing and the MA in English Studies at Western Washington University . She is the author of four essay collections, including Listening Against the Stone , Blessing of the Animals , and Season of the Body . She also co-authored Tell It Slant: Creating, Refining and Publishing Creative Nonfiction and The Pen and The Bell: Mindful Writing in a Busy World . Her work has received six Pushcart Prizes.

Miller’s Brevity craft essay is adapted from an August 2014 craft talk she presented at the Rainier Writing Workshop .

| says: Jan 30, 2015 |

| says: Feb 3, 2015 |

| says: Feb 14, 2015 |

| says: Mar 31, 2017 |

| says: Dec 15, 2017 |

| says: Feb 2, 2021 | It is truly inspiring to see you take the form of rejection letters, something most of us, if not all, are afraid of. We tend to see them as a closed doors, an opportunity missed or taken away. There’s always a wave of disappointment when you see “we regret to inform you” amongst the sea of words they use to comfort you in your state of rejection, but what I admire about your rejection letters is that there’s always a lesson to take away from each and every one. These weren’t written to just show the many hardships in your life, the pain you’ve experienced and shared. Most can relate to these hardships, most have experienced them. This is the first time that I’ve seen someone give themselves criticism, and take away important lessons from each misfortune or rejection that has occurred in their life. |

| Name required | Email required | Website |

XHTML: You can use these tags: <a href="" title=""> <abbr title=""> <acronym title=""> <b> <blockquote cite=""> <cite> <code> <del datetime=""> <em> <i> <q cite=""> <s> <strike> <strong>

Click here to cancel reply.

© 2024 Brevity: A Journal of Concise Literary Nonfiction. All Rights Reserved!

Designed by WPSHOWER

The Essay as Bouquet

"Hermit crab" essays can take many forms, both natural and not

Ambrose Bierce, the American editorialist and journalist, wrote in his 1909 craft book, Write It Right , that “good writing” is “clear thinking made visible,” an idea that has been repeated and adapted by countless writers over the past century. My own addition would be to add that the act of lyric essay writing not only makes thoughts visible but also institutes order and layers meaning when it is not always immediately apparent. And although ideas may begin free-form or as stream of consciousness, on the page or screen, we make the jump from internal to external. We craft them into a form, whether chronological or otherwise. One such approach to form is the “hermit crab” essay, so named by Brenda Miller and Suzanne Paola in their craft book Tell It Slant . Miller later defined it in an article for Brevity as “adopt[ing] already existing forms as the container for the writing at hand, such as the essay in the form of a ‘to-do’ list, or a field guide, or a recipe.” This approach creates meaning by juxtaposing the personal story with its imposed “container,” allowing the more traditional narrative to be in conversation with our personal, cultural, and/or scientific assumptions and understandings of the chosen form.

“Hermit crabs,” Miller explains, “are creatures born without their own shells to protect them; they need to find empty shells to inhabit (or sometimes not so empty; in the years since I’ve begun using the hermit crab as my metaphor, I’ve learned they can be quite vicious, evicting the shell’s rightful inhabitant by force).” Ironically, however, most containers that writers find are of the nonorganic variety: a shopping list, a course syllabus—not unlike the hermit crab who makes its home inside a bottle cap. Here, we will look at a few examples that do employ natural forms as a container, encouraging a conversation between the human-made and the natural world.

Chelsea Biondolillo’s “On Shells” from Essay Daily is, at first glance, a fragmented essay that alternates between the narratives of the author learning to beachcomb as a child, the author becoming a writer and teacher, and the background on shell collectors. At first, it appears the essay resists form when our author implies she didn’t initially embrace the imposed form of a hermit crab essay because it felt contrived. But as we move through the essay, the fragments take on their own form: that of shell collecting and of nature itself. Biondolillo tells us at the end that she has learned that writing “practice is inefficient by design. Collect as many tools and forms and voices and structures as you can so that you are as well-equipped as possible when you sit down to work.” So is beachcombing a practice of collecting the best of random bits, your own practice of creating order. She says she has learned not to be as “worried about the prize at the end of the page” as she once was; every essay we read and write will have a literal end, but there will also never be an end. The essay is about the journey, the collection of random bits, and what the resulting collection means when the pieces are looked at as a whole. And so Biondolillo’s imposed form as an act of shell collecting, reinforced by the small pictures of shells on the page between each fragment, helps illustrate that while nature can be random, as we find meaning in nature, so we also find that this randomness can—and does—forge its own form.

Yet one may also rightfully argue that nature is not entirely random, but has developed clear and consistent taxonomies, cycles, and behaviors. In Jennifer Lunden’s “The Butterfly Effect” (first published in this magazine), we learn about the life cycle of butterflies in a series of encyclopedia-like entries that also serve as the form to tell the story of the author’s own connection to butterflies, beginning in adolescence. Yet, in the early sections, like “Metamorphosis,” “Migration,” and “Habitat,” we learn as much about how these terms apply to our author’s own life as to the butterflies she is traveling, in this essay, to see.

And then our narrative—and our encyclopedic structure—spins outward. We learn about “The Butterfly Lady,” who found healing amongst the butterflies in California. The threads of these three parallel stories—the author’s, the Butterfly Lady’s, and that of the butterflies themselves—woven together form a single whole, a container. Is the container the form of the scientific encyclopedia entry? If so, we can reflect on what this says about humans imposing form on nature; after all, it is we who insist on categorization, on creating a narrative out of the sometimes disparate layers of a natural phenomenon. Or is our container the cocoon that is spun outward, protecting the chrysalis as it transforms? I would argue it is both: our encyclopedia headers look outward to “Monsanto” and “Global Warming,” and how these affect the environment not only of the butterfly but also of the author, and, in fact, of all humans. This form—or, one might argue, this dual form—reflects human imposition on nature as well as the inverse: how we define nature, yes, but also how our decisions affect it. The repetition of the headers “Migration” and “Habitat” also creates a cyclical movement often at odds with human written narration, though it is frequently seen in nature: in seasons, metamorphosis, life and death. As these threads diverge and converge, we also see wildness and humanity doing the same, ending with our word for a natural occurrence—susurrus—which would exist whether humans witnessed and named it or not.

Finally, Julie Marie Wade’s “Bouquet,” originally published in Third Coast and reprinted in her book Wishbone: A Memoir in Fractures , is itself a bouquet that pairs the name, horticultural descriptions, growing tendencies, and cultural relevance of different kinds of flowers with scenes or reflections. The personal reflects the natural, both through the flowers’ innate tendencies and the symbolism culture imposes on them. For example, a brief explanation of why the long-lasting cornflower is known as “bachelor’s button” is paired with the story of a relationship as well as Wade’s struggle to accept her own sexual identity. What makes the bouquet an appropriate container is the interplay of the natural characteristics of each flower—those that humans cannot control—with the cultural import we have given many of these flowers, as well as the symbolism of the bouquet as an object. The bouquet is a human form made of nature—a collection of (in this case) disparate flowers, cut and contained and most often given as a gesture of love. A bouquet, too, is a sum of its parts. Each flower can and does exist on its own in the wild, but in relation to others in our human-made form, each plays a particular role. Here is the author’s literary bouquet: a collection of the personal blooms that make up the story she is telling—a bouquet the reader believes, by the end of reading, to be a gift to her beloved. As in both Biondolillo’s and Lunden’s essays, there is always the tension of seeing a natural form in its native habitat—a shell, a butterfly, a flower—and the human manipulation of it.

Can we ever not see nature through the lens of our humanness?

As I began my own investigation into nature-influenced hermit crab essays, I thought I would find numerous essays that used the infinite unblemished forms found in our natural world as a perfect metaphor and container for our very human and imperfect stories. But I found it challenging to unearth many examples of nature-as-form, and those I did find built upon the interplay of the natural world and human influence. Perhaps this only makes sense: can we ever not see nature through the lens of our humanness, especially as we strive to use it as a container to help make sense of our own stories and experiences?

Perhaps Biondolillo best expresses the essence of what a hermit crab essay is: “Acuity to see the unbroken curve of aperture against all of the chips and shards the sea has thrown up, to see the unblemished whorl, the striations in deep relief among the smooth nubs of wood, the distracting pebbles of glass, the wet strings and sheets of seaweed, already rotting in the first light of morning.” At first reading, I interpreted this to be an appreciation of nature and an effort to emulate its “unbroken curve” and “unblemished whorl” in one’s writing. But maybe that’s not the whole story. The hermit crab essay as inspired by nature can be formed from the broken “chips and shards” and the “distracting pebbles of glass.” Are these imperfect bits manmade or from nature? And does it matter? They are all part of the world in which we live: nature influenced by humans and humans inspired by nature—and all of us if not rotting, then certainly evolving in each new morning’s light.

Writing the Hermit Crab Essay, with Sarah Earle

The Hermit Crab is an essay whose tender, vulnerable truth seeks an outside structure with which to contain it. Just like the hermit crab itself, which spends its life living in a succession of ever-changing mollusk shells, writers go about combing life’s ocean floor for carapaces for their own material. These forms might not, at first glance, seem literary: a recipe, a how-to guide, a real estate ad. Once the writer’s story starts to inhabit the form, there is no telling how that story will grow. In a panel discussion, writer Brenda Miller, who along with Suzanne Paola coined the essay form, explains: ‘[the process of moving into a form] often shows how content wants to expand the story beyond the form, just as a hermit crab outgrows its shell, nudging the boundaries.”

In this half-day class, students will be introduced to the concept of the hermit crab essay and spend time reading and discussing published examples together. Then, they’ll explore, feeling out their options, picking up shells and deciding if their heft, size, and weight feel right for the story they will contain. By the end of the class, students will have generated the first draft of a hermit crab essay and have the opportunity to gain feedback from teacher and peers about how they might move their essay forward.

This workshop will be held online.

Saturday, October 15, 9:30 a.m. – 12:30 p.m. ($75)

For seven years, Sarah Earle was a lecturer in first-year composition and English as a second language at the University of New Hampshire. She has also taught creative nonfiction at St. Paul’s Academic Summer Program in Concord, NH, and worked as an editor of Outlook Springs Literary Magazine. She holds her MFA in nonfiction writing from UNH; you can read her essays in Bayou Magazine and The Cobalt Review , and her fiction in The Rumpus and The Carolina Quarterly.

Advanced Essay Writing: The Hermit Crab Essay

Have you ever read a nonfiction essay written in letters, lists, or emails? If you answered yes, you have read a hermit crab essay. The hermit crab essay is a nonfiction essay in which the writer adopts an existing form to contain their writing, such as recipes, to do lists, and/or field guides. In this six-week course, you will read through examples of hermit crab essays and discuss their meaning, construction, and mechanics. Through a series of writing exercises and peer workshops, you will produce your own hermit crab essay that uses unexpected forms to create unique writing.

Class Details

Genre : Nonfiction Level : Advanced Format : Craft and generative workshop with writing outside of class and peer feedback. Location : This class takes place remotely online via Zoom. Size : Limited to 12 participants (including scholarships). Suggested Sequence : Follow this class with a craft and/or generative nonfiction workshop, a feedback course, or a publishing course. Scholarships : Two scholarship spots are available for this class for writers in Northeast Ohio. Apply by December 1. Cancellations & Refunds : Cancel at least 48 hours in advance of the first class meeting to receive a full refund. Email [email protected].

Work with the best...

Negesti Kaudo is a Midwestern essayist who holds an MFA in creative nonfiction from Columbia College Chicago. She is the author of Ripe: Essays and the youngest winner of the Ohioana Library Association's Walter Rumsey Marvin grant (2015) for unpublished writers under 30.

This class takes place remotely online via Zoom.

Cleveland oh, related classes.

Start Your Memoir from Scratch - September 2024

Finish That Essay: Revising and Submitting Your Work for Publication

Intermediate Memoir

Never miss a moment, sign-up for our newsletter and be the first in line for exclusive offers and updates on all things lit cle..

CLASSES & WORKSHOPS

Events & programs, anthologies, memberships, community resources, our services.

Hermit Crab Essay

If you’re looking for a unique way to write an essay, to bend the genre, how about writing a Hermit Crab Essay? “This kind of essay appropriates existing forms as an outer covering, to protect its soft, vulnerable underbelly,” Brenda Miller and Suzanne Paola write in their co-authored non-fiction craft book, Tell It Slant . The metaphor of the hermit crab is fitting. They are born without shells, and need to find an empty shell in order to protect themselves. As Brenda and Suzanne write in their book, the same goes for “an essay that deals with material that seems born without its own carapace—material that is soft, exposed, and tender, and must look elsewhere to find the form that will contain it.”

This past summer, I attended a hermit crab essay class taught by Brenda Miller at Vermont College of Fine Arts . She began by having us list the numerous existing “outer coverings.” Here’s a sampling of what we came up with: recipe, field guide, Craig’s List ad, bibliography, syllabus, math problem, text message, prescription side effects, blog post, phone call, email, love note, resume, restaurant menu. She then asked us to choose one and see what creative content the form suggests. As Brenda noted in her piece about the hermit crab essay published in Brevity , “This is the essential move: allowing form to dictate content. By doing so, we get out of our own way; we bypass what our intellectual minds have already determined as “our story” and instead become open and available to unexpected images, themes and memories.” Also, this form gives “creative nonfiction writers a chance to practice using our imaginations, filling in details, and playing with the content to see what kind of effects we can create.”

Since I was in the mood “to play with the content” on the day I attended Brenda’s class, I chose side effects of a prescription narcotic:

This narcotic, if taken as directed, will result in a lasting high, and a sense of total freedom. Within thirty minutes of taking this narcotic, your attitude will change from worry to “I don’t give a damn about anything.” You will be able to eat as much as you want of whatever you like – Devil Dogs, Twinkies, potato chips – and not care if you gain weight. If anything, you will likely lose weight. There is no maximum dose. It is perfectly fine to operate a vehicle, vessel, Saturn V Rocket or The Millennium Falcon, or any kind of machinery, and even drink alcohol while taking this narcotic. If you experience any of the following we recommend you take an extra dose immediately: a sudden ability to speak in parseltongue, the strength and flexibility to maintain warrior three pose for more than fifteen minutes, the brain energy to move objects with your mind, the ability to convince your spouse that you are no good in the kitchen, the acting skills to persuade your boss to allow you to work ten hours a week and get paid for forty, and the chutzpah to convince your mother-in-law that she is wrong about most things.

Warning: Literal interpretation of the above essay is dangerous and harmful to your health.

Do you have an existing “outer covering” to add to the above list? Do you have an essay in need of a shell? Since the new year is only two days from now, why not write an essay in the form of a resolution list? If you’ve already found your protective shell, please don’t be shy about sharing it.

Happy New Year!

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Recent Posts

- Being Human

- The Forgiveness Project

- Melissa Cronin in Conversation with Lynn Lurie, Author of Museum of Stones

- Pearl of Wisdom for Writers

- Meaning in Things

Recent Comments

- Melissa on Meaning in Things

- Tonya Clay on Meaning in Things

- Working at Walmart on Being Human

- bahis siteleri on Benefits of Being a Military Nurse

- Melissa on What I learned at the Muse & Marketplace Conference for Writers

- Book Reviews

- Brain Health

- Brain Injuries

- Forgiveness

- Health Care

- Movie Reviews

- Musings on Aging

- Older Drivers

- Posttraumatic Stress Disorder

- Testimonials

- The Human Condition

- Volunteerism

Sign Up For My Monthly Newsletter!

Five thought-provoking tidbits I find worth sharing - writing, art, books, helpful links.

You can unsubscribe anytime.

Thank you for signing up!

Enjoy this blog? Please spread the word!

- Skip to primary navigation

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

weekly conversations on the world of telling true stories, by Proximity

39 January 18, 2018 Proximity's Quarterly

(Re)using Found Forms: The Hermit Crab Essay

From the front a hermit crab looks like a hand, a red-fingered fist, curling out of a shell.

This seems an appropriate metaphor for a hermit crab essay.

According to Brenda Miller and Suzanne Paola in their craft book Tell It Slant: Writing and Shaping Creative Nonfiction , a hermit crab essay is one that “appropriates other forms” the way a hermit crab appropriates another’s shell.

Thus a hermit crab essay could be told in the form of a syllabus , drug facts , body wash , Google maps , footnotes , the pain scale , apologies .

Miller and Paola claim that the form, the “outer covering,” of a hermit crab essay, works to “protect its soft, vulnerable underbelly.” They claim that this kind of essay “deals with material that seems to have been born without its own carapace—material that’s soft, exposed, and tender and must look elsewhere to find the form that will best contain it.”

I wonder, though, if the shell provides containment more than protection, parameters more than safety. Like Robert Frost playing tennis with a net.

A shell can protect but it can also hold something that needs to be held—the plumule of a seed, the inside of an egg, the powder and shot of a shotgun shell. All these things are—eventually—meant to be released.

The hand emerges from the shell.

I wrote my first hermit crab essay by accident. I was on a residency at the wonderful Virginia Center for the Creative Arts and I was toying with the idea of writing about a forbidden crush in the form of a timeline—what would its mile markers be? how long would it take to subside? I didn’t consciously think of this as a hermit crab essay. In fact, I wasn’t really consciously thinking at all. But as I was unconsciously thinking, I decided to move the gigantic desk in my studio so that it faced a window. I pulled the desk away from the wall—and then I pulled my back.

It hurt – bad – so bad I couldn’t stand up straight. I crouched over my computer to ask the internet how to fix a torn muscle and WebMD gave me the answer: ice, an anti-inflammatory, elevation, protection. And then it came to me: Isn’t the heart a muscle too? I had found my form.

It’s true that a transgressive crush is a vulnerable subject to write about. But I didn’t seek a hard shell to protect that vulnerability. Instead I thought the contrast of form and content would serve the essay as a whole—a hot, passionate, messy subject encased by a cool, prescriptive, medical form.

Besides, aren’t all essays in some way vulnerable as we try ( nous essayons ) to express and explain what we think and how we feel—and why?

Armor protects, but it also limits your ability to see, to move, to flex, to adapt. Better to hold an egg, a seed, an explosion.

Better to be the hand reaching out of the shell.

Look for Proximity’ s next themed issue, REUSE, to go live within the week and find your way through our complex collection of true stories. And then perhaps find your way back again.

Randon Billings Noble is an essayist. Her lyric essay chapbook Devotional was published by Red Bird in 2017, and her full-length collection Be with Me Always is forthcoming from the University of Nebraska Press in 2019. Her hermit crab essay “The Heart as a Torn Muscle,” originally published in Brevity , will appear in the anthology The Shell Game: Writers Play with Borrowed Forms , edited by Kim Adrian and out from the University of Nebraska Press in April. @randonnoble

Reader Interactions

January 18, 2018 at 1:44 pm

Thank you for this! It reminded me to go back to the workshop you taught last summer and remember how excited I was to have been introduced to so many possibilities of form. I need to stay that excited and not let feedback, rejections and self-doubt slow me down like it has the past few months. I have to get back to writing for me.

February 8, 2018 at 12:43 pm

wow! nature is amazing. cheers!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Currently you have JavaScript disabled. In order to post comments, please make sure JavaScript and Cookies are enabled, and reload the page. Click here for instructions on how to enable JavaScript in your browser.

Yes, add me to your mailing list.

Notify me of follow-up comments by email.

Notify me of new posts by email.

Sign up for Proximity's TinyLetter!

Recent Posts

- Chelsea Biondolillo’s “The Skinned Bird”

- The Time I Changed History With a Fourth-Grade Writing Assignment

- Let It Be: The Lilac in US Poetry

- The Rhythm of Chronic Illness: A Review of “You’ve Been So Lucky Already” by Alethea Black

- An Interview with Alison Powell, Proximity’s 2018 Essay Prize winner

- Beauty In the Mundane: A Review of the Podcasts “Everything Is Alive” and “Wonderful!”

CRAFT: The Hermit Crab Essay: Forming a Humorous Take on Dark Memoir by Susan Mack

June 6, 2022.

Many of us feel challenged when trying to add humor to a darker memoir piece. Perhaps we don’t think of ourselves as funny, we don’t want to cheapen the depth of a traumatic experience with a formulaic or cheap joke, or we don’t think the experience was funny. We may worry humor is so subjective that our readers won’t get our jokes or won’t find them authentic and relatable.

The hermit crab essay offers an excellent opportunity to experiment with respectful humor as a tool to help readers engage with darker topics.

In The Psychology of Humor, an Integrative Approach , Rod Martin describes a longstanding philosophy of humor:

“the perception of incongruity is the crucial determinant of whether or not something is humorous: things that are funny are surprising, peculiar, unusual or different from what we normally expect.”

Martin goes on to argue that the greater the degree of incongruity, the more tension builds, and the greater the emotional release through humor.

By this definition, one can argue the hermit crab essay is inherently humorous. It purposely delivers content inside of an incongruous structure, just as hermit crabs must adopt external shells to protect their soft bodies. The contrast between form and content offers an opportunity for overt humor that in no way conflicts with the intensity of the subject matter.

Brenda Miller’s “We Regret to Inform You” is one of the better-known hermit crab essays. Inspired by publishers’ rejection letters, Miller writes a series of speculative letters for non-writing-related rejections throughout her life, beginning with “Dear Young Artist: Thank you for your attempt to draw a tree. We appreciate your efforts … but your smudges look nothing like a tree.” The essay then offers letters for teenage rejections: school dances, dance team, trying to act. Then it turns to deeper rejections: miscarriage, boyfriends, the role of stepmother. This last one shows a characteristic of the form, which, while humorous, allows for a deeper exploration of the reasons behind the rejections. Miller writes the following as one of the reasons why her application for stepmother was rejected:

“Though you have sacrificed your time and energy to support this family, it’s become clear that your desire to be a stepmother comes from some deep-seated wound in yourself, a wound you are trying to heal. We have enough to deal with — an absent mother, a frazzled father. We don’t need your traumas in the mix.”

This form allows Miller to use the children’s voice to tell us, in a few words, the real reason why the marriage doesn’t work. Including this heavily emotional description inside such a cold, rejection-letter format creates an incongruity that is humorous, insightful, and sad at the same time. If we laugh, we laugh in empathy with the narrator’s pain. Miller ends the series of rejections with one acceptance, titled “Dear New Dog Owner,” which provides not just contrast with the rejections but also a somewhat universal panacea for rejection: a dog. The incongruity of form allows a succinct exploration of larger rejection, including a full range of light and dark, funny and sad, all in the same essay.

Effective use of the hermit crab structure doesn’t have to be limited to standalone essays. In Pat Boone Fan Club , Sue Silverman uses the hermit crab form in one subsection of a larger essay about her high school rival’s suicide, while other sections have more conventional narrative structures. This section, titled “The Love Triangle as a Problem of High School Geometry,” is almost self-explanatory. Silverman uses the set, logical structure of math to try to explain the free-form rule-breaking challenge of a love triangle. The narrator’s difficulty with math serves as a metaphor for the difficulty of navigating the complex calculus of teenage love:

“But suppose this geometric proof of love is merely a postulate? For if Christopher smiles at Lynn then _______. I don’t want to fill in the blank. Memorize the following equation as if it’s hard evidence: Lynn hates me as much as I hate her. This hate = the amount we both love Christopher.”

The mathematical structure contrasts with the emotional complexities of human — particularly teenage — romance. It offers a sense of the sweet innocence of the teenage mind wrestling with the relatively new world of romance, along with the older writer’s understanding that this will never fit into a simple mathematical equation. This structure allows humor, sweetness, and empathy to exist in the same moment. Its placement immediately after the subsection introducing the rival’s suicide provides a welcome variety of emotional pacing. The few paragraphs of humorous description effectively support the intensity of the longer essay.

Many other authors use hermit crab techniques as humorous moments inside larger works. Jenny Lawson uses a one-sided conversation with her husband on Post-it notes and imaginary author talks to give alternate structures in Furiously Happy. Many authors include humorous lists in their work. There are endless options for playing with hermit crab form inside CNF. And with them, endless options for playing with contrast between form and content, title and subject matter, and even as-yet undiscovered humorous juxtapositions.

Share a Comment Cancel reply

Contributor updates.

Alumni & Contributor Updates: Summer 2024

Alumni & Contributor Updates: Early 2024

Contributor Updates: Fall 2023

Contributor & Alumni Updates: Spring 2023

Essays in Strange Forms and Peculiar Places: ‘The Shell Game’

The term “hermit crab essay,” coined in 2003 by Brenda Miller and Suzanne Paola in their book Tell It Slant: Writing and Shaping Creative Nonfiction , refers to essays that take the form of something un-essay-like—such as a recipe, how-to manual, or marriage license—and use this form to tell a story or explore a topic.

These essays, like the creatures they’re named after, borrow the structures and forms they inhabit. And these borrowed homes, in turn, protect the soft, vulnerable bodies of the crabs within. As Miller and Paola write in their original description of the genre:

This kind of essay appropriates other forms as an outer covering to protect its soft, vulnerable underbelly. It’s an essay that deals with material that seems to have been born without its own carapace—material that’s soft, exposed, and tender and must look elsewhere to find the form that will best contain it.

Hermit crab essays are a fascinating genre, one that I’m drawn to as both a reader and a writer. There’s something about them that represents the spirit of our era—with our infinite distractibility and our distrust of meta-narratives. They capture, perhaps, the inability of traditional storytelling to tell our most traumatic, fragmented, and complex stories—and our longing for structures that can.

Hermit crab essays de-normalize our sense of genre, helping us to see the way that forms and screens, questionnaires and interviews all shape knowledge as much as they convey it. For essays like these, message is always, at least in part, the medium.

Miller says in her foreword to The Shell Game that “with every iteration, both the hermit crab creature and the hermit crab essay become more deeply understood, and the possibilities for the form grow by the day.” And it is indeed a form that’s constantly growing and expanding. As long as there are new forms and structures created in the world, there are new possibilities for hermit crab essays.

Kim Adrian’s introduction to the volume is itself a hermit crab essay. Subtitled “A Natural History of the North American Hermit Crab Essay,” the introduction takes the form of a field guide about hermit crab essays, as if they were living creatures. In a section called “Number of Species,” for instance, she says that the family is “theoretically infinite, realistically somewhere in the thousands. Maybe tens of. Some of the more conspicuous include: grocery lists; how-to instructions; job applications; syllabi and other academic outlines; recipes; obituaries; liner notes; contributors’ notes; chronologies of all orders; abecedarians of all types; hierarchies of every description; want ads; game instructions,” along with dozens of other examples. In other words, the forms that hermit crab essays can take are as endless and ever-changing as human culture itself.

Adrian raises in her introduction the possibility that hermit crab essays could “be a self-limiting phenomenon: a somewhat charming blip of literary trendiness.” Time will tell, she says, but it’s also possible:

…that instead of disappearing like a spent trend, the hermit crab essay may yet spawn an entire new breed of essays—essays we can’t even imagine from here, essays that refuse to draw a line between fact and fiction, that refuse even to acknowledge such a line, and that throw on disguises of every description…in order to more fully inhabit some internal truth and in this way do what the best specimens of the noble order Exagium have always done: get to something real.

It’s interesting to note, as she says, that one of the things these essays do is to “refuse to draw a line between fact and fiction.” Many hermit crab essays are a strange hybrid between fact and fiction, calling attention to their constructedness and their made-up qualities even as they presumably tell “true” stories and are rooted in actual experiences. It’s difficult to consider them strictly nonfiction, since they are themselves inventions. When an essay in this volume takes the form of a legal document or a marriage license, after all, it’s pretending to be those things in order to tell a deeper story, or, as Adrian says, to “get to something real.”

It’s no accident, I think, that this form is gaining popularity precisely at a moment in American culture when the distinctions between fact and fiction are becoming increasingly blurry. That’s not to say that hermit crab essays don’t teach us to think critically about that blurriness. Rather, they do just the opposite: They call attention to the ways that cultural forms and expectations create reality. They make us see something about the forms and the stories they embody, helping us to understand how the forms of our culture both shape and limit our understanding of the world.

The essays in this volume cross a lot of territory and, as would be expected, take many forms. One of my favorites is “Solving My Way to Grandma” by Laurie Easter . It takes the form of a crossword puzzle in order to tell the story of the narrator’s coming to terms with becoming a grandmother. Since I love word puzzles, I worked on the puzzle as I read the essay, which was composed of small snippets of story turned into clues. Here, for instance, is 1 Across: “‘Mom, I have something to tell you. You might want to sit down.’ When my daughter said this, my first thought was Uh-oh, who died? Not Oh my god, she’s pregnant. (Expect the _______).”

Solving the puzzle while reading the essay lets the reader experience the narrator’s own process of puzzle-solving about her life. It’s a moving essay that works especially well because the form and the content are so well-matched. Reading this essay is a visceral experience in puzzle-solving.

The collection is full of similarly surprising and delightful essays. Sarah McColl ’s “Ok, Cupid,” for instance, uses the form of a dating profile for self-revelation, with the narrator answering questions like “What I’m doing with my life” with elaborate and seemingly tangential answers that actually become more truthful than a real dating profile ever could.

Brenda Miller’s “We Regret to Inform You” is a brilliant collection of imagined rejection letters from art teachers, dance teams, and would-be boyfriends and husbands. The essay ends, finally, with an acceptance letter from a pet rescue, congratulating her on the adoption of her new dog—a letter that comes in stark and moving contrast to the years of rejection.

The essays in this collection bring with them a sense of hope about literature and its capacity for evolution and change. In Tell It Slant , Miller and Paola tell those interested in writing hermit crab essays to look around and see what’s out there: “The world is brimming with forms that await transformation. See how the world constantly orders itself in structures that can be shrewdly turned to your own purposes.”

In a postscript to The Shell Game , there’s an eight-page list by Cheyenne Nimes of many possible forms for hermit crab essays, from game show transcripts to eBay ads. I couldn’t help reading this as a list of writing prompts, circling some that I’d like to try. It’s a fitting way to end a volume that is as much an inspiration for other writers as it is a definitive collection of a constantly evolving genre.

Ultimately, maybe it’s this promise of transformation and adaptation that makes hermit crab essays so appealing. They encourage us to move forward, and they show us how many different paths we might take.

Vivian Wagner lives in New Concord, Ohio, where she teaches English at Muskingum University. Her work has appeared in McSweeney’s Internet Tendency, Creative Nonfiction, Slice, and many other publications, and she’s the author of Fiddle: One Woman, Four Strings, and 8,000 Miles of Music (Citadel-Kensington), The Village (Kelsay Books), and Making (Origami Poems Project). Visit her website at www.vivianwagner.net .

Most Anticipated: The Great Summer 2024 Preview

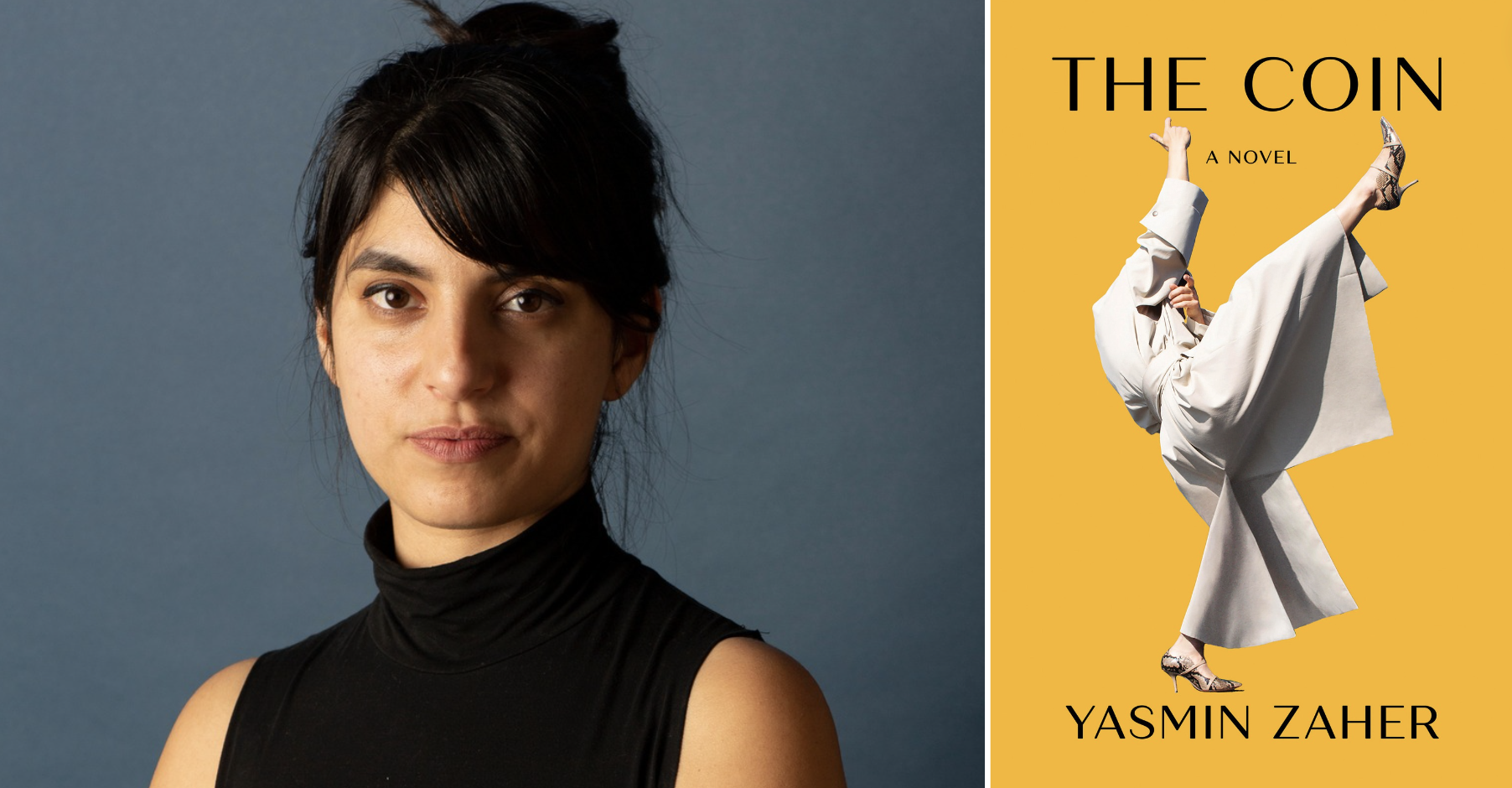

How Yasmin Zaher Wrote the Year’s Best New York City Novel

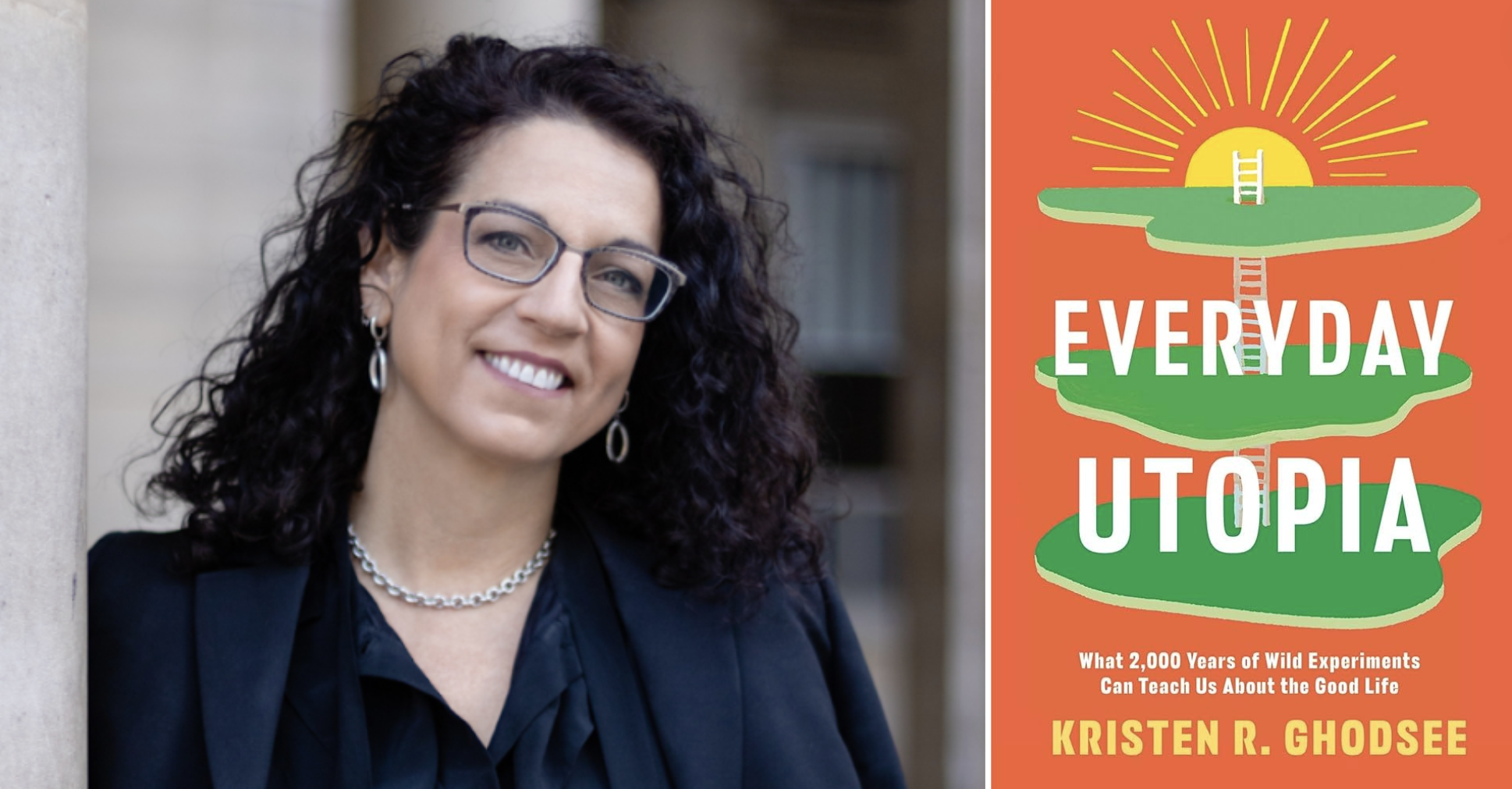

History Gives Kristen R. Ghodsee Hope for the Future

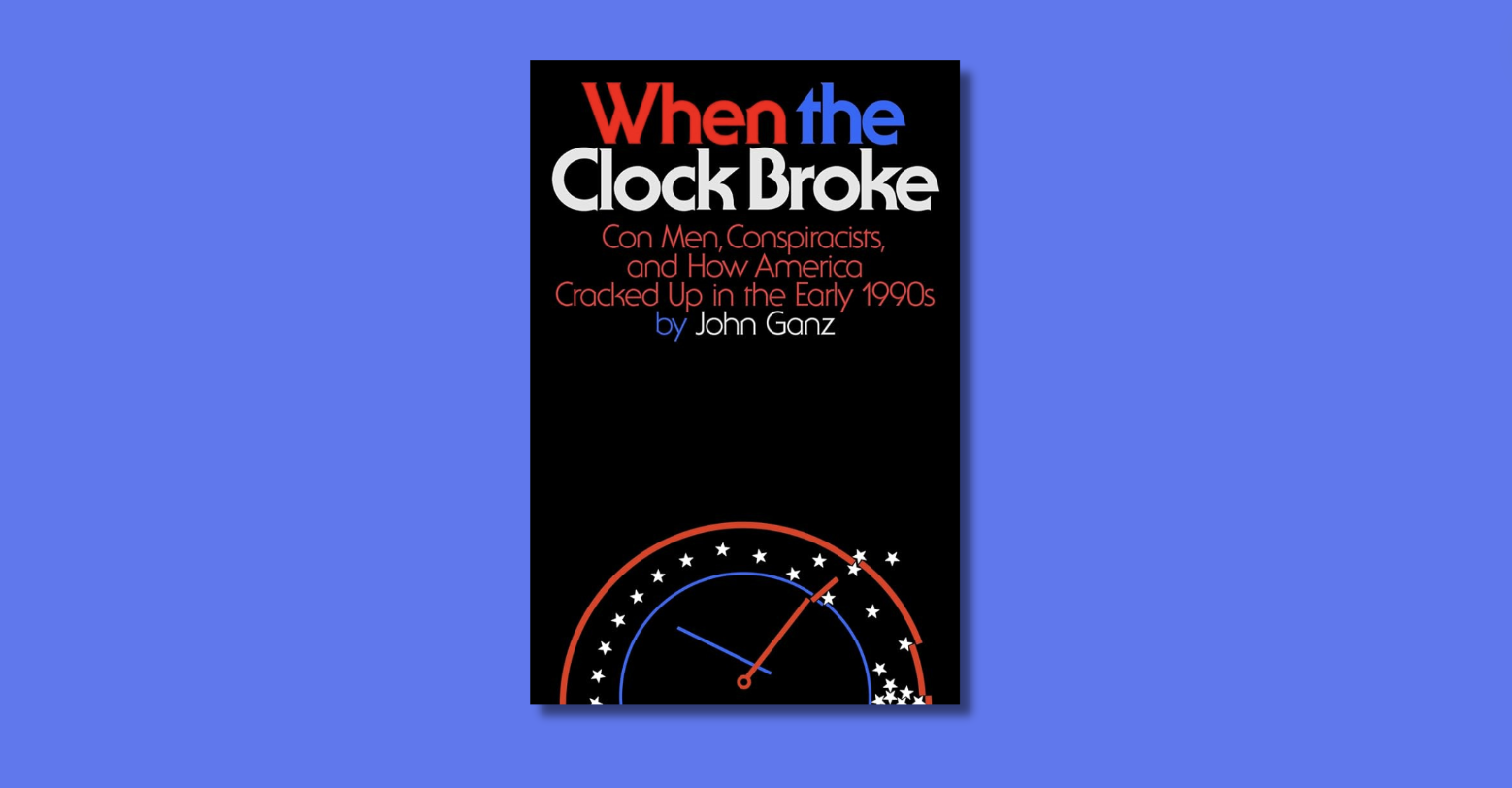

Things Got Weird: On the Early ‘90s Crack-Up

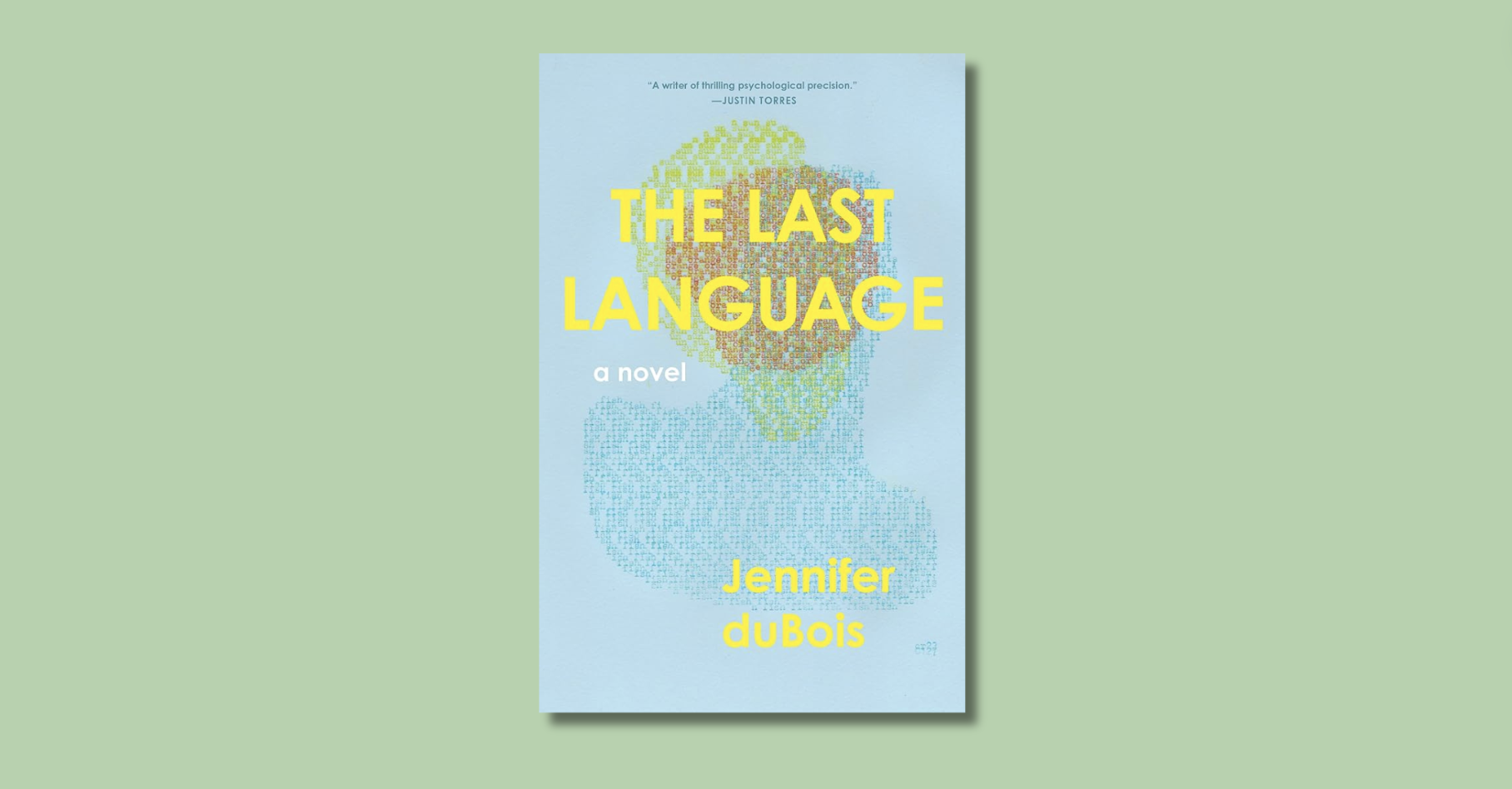

The Unstable Truths of ‘The Last Language’

Same River, Same Man

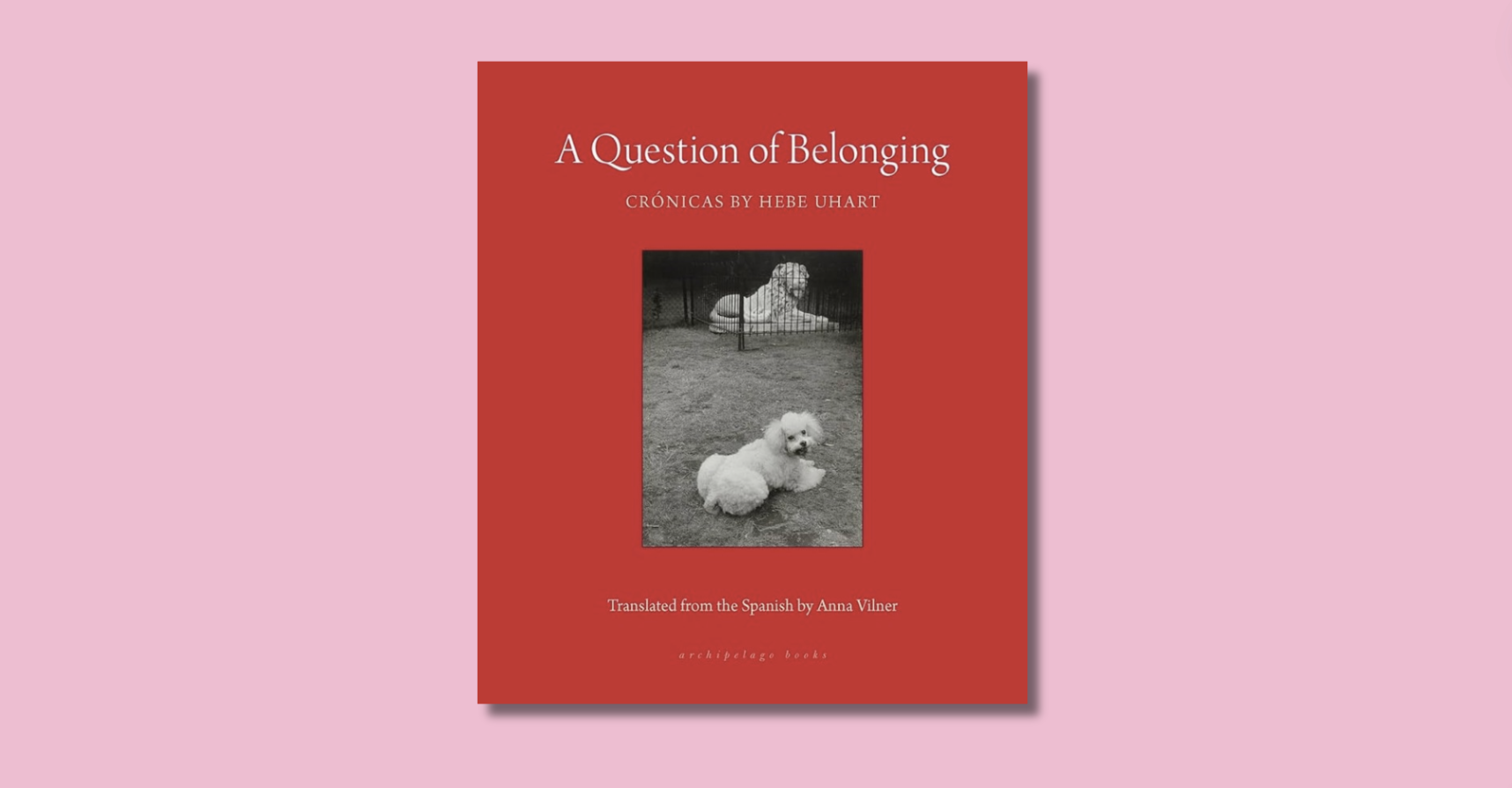

The Beguiling Crónicas of Hebe Uhart

Jazz Remains the Sound of Modernism

Ed Asher Briant

Printmaking, Poetry, and Bookmaking.

Hermit Crab Essay

On Monday some of us attended a presentation by Randon Billings Noble, a candidate for teaching Creative Non Fiction at Rowan.

She read an example of what she referred to as a Hermit Crab essay.

In nature a Hermit Crab uses shells discarded by the sea creatures, for example you might find a hermit crab living in an old oyster shell.

I liked this approach to writing a personal essay and I think you will too.

The approach is quite simple.

Like a hermit crab you borrow the format of another piece writing––probably a non-creative form––and build your essay using that type wof structure.

This seems to work best when the essay is deeply personal––almost to the point of being confessional––and the format is highly prosaic (‘prosaic’ is the opposite to poetic, and means dry, dull, and boring), thus giving the maximum tension between to the two forms.

Our first task is to brainstorm some of the possible formats we could use.

Reseach Paper

Project Proposal

Instruction Manual

Lesson Plan (Hah!)

Business Letter

Real Estate Flyer

For Sale Notice

Event Poster

Greeting Card (or a series of greeting cards)

Description of a work of art (painting, piece of music, sculpture)

Museum, Brochure.

There are many other formats, but the next step is to look at the potential of some of them, and the greatest potential probably lies with the ones you’re most familiar with. For example, I trained as an artist, so the idea of viewing a scene from my life as a classical painting in a museum appeals to me––just because I spend a lot of time in museums.

Sylvia Plath did this too.

If you’ve recently been trying to buy or sell something on ebay or craigslist you might do the sales blurb.

At this point it’s good to ask ourselves why we’re doing this.

Yes, it could be fun, and fun makes good writing and reading, but in creative non-fiction we’re trying to go deeper.

What we are achieving here has been referred to as getting ‘out of our own way.’

In other words, we know what we want to write about, but this exercise is going to force us to reconsider how we’re going to write about it, and open ourselves up to the unexpected.

Do we really want to write about lost love as maudlin first person account? Would that really get the point across? Could it be more effective if the account was written as a set of instructions.

Here are some examples from essayist Brenda Miller:

Rejection Letter

April 12, 1970

Dear Young Artist:

Thank you for your attempt to draw a tree. We appreciate your efforts, especially the way you sat patiently on the sidewalk, gazing at that tree for an hour before setting pen to paper, the many quick strokes of charcoal executed with enthusiasm. But your drawing looks nothing like a tree. In fact, the smudges look like nothing at all, and your own pleasure and pride in said drawing are not enough to redeem it. We are pleased to offer you remedial training in the arts, but we cannot accept your “drawing” for display.

With regret and best wishes,

The Art Class

Andasol Avenue Elementary School

October 13, 1975

Dear 10th Grader:

Thank you for your application to be a girlfriend to one of the star players on the championship basketball team. As you can imagine, we have received hundreds of similar requests and so cannot possibly respond personally to every one. We regret to inform you that you have not been chosen for one of the coveted positions, but we do invite you to continue hanging around the lockers, acting as if you belong there. This selfless act serves the team members as they practice the art of ignoring lovesick girls.

The Granada Hills Highlanders

P.S: Though your brother is one of the star players, we could not take this familial relationship into account. Sorry to say no! Please do try out for one of the rebound girlfriend positions in the future.

This is one of my own:

How to Make Your Home Feel Really Empty in Twelve Steps.

First, place everything you can lift into boxes you retrieved from a dumpster behind a liquor store

Second, carry it all as far away as you can.

Third, If you still have a friend, or an almost-friend––even a sort-of-friend––and perhaps a friend-of-a-friend,

Have them help you take out the things too heavy for you to manage alone.

Fourth, Use a wineglass to trap all the spiders, bees, flies, moths, and roaches, then take them outside and release them.

Fifth, Vacuum every cranny if you have crannies.

Sixth, Vacuum every nook if you have nooks.

Seventh, Vacuum every niche if you have niches.

Eighth, Peel off the sheetrock, roll up the carpets, and wrap the wiring,

Ninth, Gather up all the joists, the boards, the studs,

Tenth, stack the doors, windows, and frames,

But leave one sill.

Eleventh, using a scientifically-proven device,

Suck out all the air, first the nitrogen, then the oxygen, then

The CO-two, the neon, the freon, and the argon.

Finally, for a finishing flourish, find a shallow basket,

Preferably at Goodwill, place it on the one remaining sill,

And arrange in it a dozen sachets of hot-sauce from a Seven-Eleven.

Then I can live there, and never be reminded of you.

Share this:

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

The Hermit Crab Essay

In progress, 6:00 - 8:00pm ct, instructor:, jennifer chesak, the porch house at 2811 dogwood pl., nashville, 37204, for members, for non-members.

Hermit crabs frequently change shells. Our writing can too, giving us a new structure—just for fun or when we feel stuck. A hermit crab essay uses the existing shell of a different form of the written word, such as a recipe, a research paper outline, a word math problem, footnotes or endnotes, an open letter, and more. In this workshop, we'll explore impactful and fun hermit crab essays, brainstorm "shells" for our writing, and craft a hermit crab essay.

Jennifer Chesak is the author of The Psilocybin Handbook for Women . She is an award-winning freelance science and medical journalist, editor, and fact-checker, and her work has has appeared in several national publications, including the Washington Post. Chesak earned her master of science in journalism from Northwestern University’s Medill. She currently teaches in the journalism and publishing programs at Belmont University, leads various workshops at the The Porch, and serves as the managing editor for the literary magazine SHIFT. Find her work at jenniferchesak.com and follow her on socials @jenchesak.

What Our Students Say

More classes.

Memory Mining

Heather hasselle, soundtrack your stories, foundations of fiction, clemintine guirado.

Creative Writing

The hermit crab essay.

Like hermit crabs finding different vessels to use as shells, essayists can repurpose different forms to tell their stories. In this class, we’ll look at unique hermit crab essays in the form of rejection letters, lists, quizzes and more, and discuss how to choose the best form to suit your essay. We’ll also experiment with writing our own hermit crab essays and discuss them in class.

All students must be 18 years of age or older.

Sorry, but there are no available courses being offered this semester.

Thoughts on developing people, organisations and leadership

Hermit crabs, writing and MBAs

I was talking to a friend who enjoys writing and she told me about the ‘hermit crab essay’ which was new to me. It is an idea that has been developed by Brenda Miller and Suzanne Paola (Miller and Paola, 2019) and further adapted by others (Writers, Tired of Rejections? Try Penning a Hermit Crab Essay – Nadja Maril, Writer & Author, n.d.).

Before I explain let me set out why I am interested in this idea. I run an MBA at the University of Chichester in the UK. It is based upon an apprenticeship scheme to support the development of senior leaders. It is a three-way relationship between the participant, the university and their manager. When I created the programme in 2018 two things were important to me. First, there would be no separate modules on HR, finance, strategy, and the like. Instead, there would be loose themes such as ‘Developing people and teams’ and creating ‘Organisational impact’ through which the participant would show their mastery of these business topics in a holistic and integrated way in their workplace. Since when has strategy ever stood on its own? Second, there would be no traditional academic essays. Now we are getting to hermit crabs. Successful organisational life is about having conversations, meetings, honing a savviness for dealing with conflicting and ambiguous information, reading and assimilating large amounts of data. And then there is establishing your credibility, making your case and creating positive impact. This is what mastery is and the MBA would reflect this.

Back to those vulnerable, house hunting, fleshy crabs. Imagine writing:

- A business case for a new investment

- A presentation that that will launch a change programme to a large group of anxious colleagues

- An article for an inhouse magazine about a new market that the department is going to explore, and the list goes on

Each form of writing has different objectives, audiences, information requirements, risks and anxieties. The way that you persuade people will be different too. For example, how do you establish your authority; what is the logical argument you need to make; and, what emotional connection do you need to make with the reader?

Adapting to these different requirements is the work of the ‘hermit crab writer.’ It means finding new forms of writing and to do so quickly, each new ‘shell’ has to be the right size, shape and colour. The process of change and adaptation can be stressful, and you can feel vulnerable. There are three interconnected factors. First, as a metaphorical hermit crab, what are your new needs, objectives and areas of development. Second, what is possible, what shells are around you that you can inhabit. For example, what form of writing can you use (PowerPoint slide decks, detailed reports with footnotes, etc), what data do you need (data and statistics or case studies and descriptions) and what writing style do is taken seriously (first person and emotive or detached and anonymous). Being a hermit crab is also about compromise, rarely do you find the perfect shell, and sometimes ‘good enough’ is the best you can get. Third, what is the context and environment where you want to succeed and protect yourself, not only the immediate crevices and nooks but also the wider ocean? This is why the metaphor of the hermit crab is useful, it gives a name to the adaptive contextual process of successful organisational life in general and writing in particular. It is a form of real-world critical adaptive masters level ability that is different from writing traditional essays on abstract business topics on marketing, HR, case studies and the like.

Miller B and Paola S (2019) Tell It Slant: Writing and Shaping Creative Nonfiction . Third. McGraw-Hill.

Writers, Tired of Rejections? Try Penning a Hermit Crab Essay – Nadja Maril, Writer & Author (n.d.). Available at: https://nadjamaril.com/2022/09/04/writer-tired-of-rejections-try-penning-a-hermit-crab-essay/?utm_source=substack&utm_medium=email (accessed 26 August 2024).

Share this:

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

Leave a comment Cancel reply

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

The hermit crab essay is a nonfiction essay style where a writer will adopt an existing form to contain their writing. These forms can be a number of things including emails, recipes, to do lists, and field guides. The hermit crab essay was first discussed in the Tell it Slant textbook by Brenda Miller and Suzanne Paola. Miller and Paola go ...

A hermit crab essay is a bit like an actual hermit crab in that it's an essay that takes on the existing form (as if a shell) of another type of writing. For instance, an essay that looks like a set of instructions or social media posts (or letters, poems, postcards, outlines, obituaries, script, footnotes, or prompts). ...

What moved me: Hermit crab essays as an opportunity to stop taking myself so damn seriously. Rich Youman, Haibun & the Hermit Crab: "Borrowing" Prose Forms. Juxtaposition is at the heart of Youman's exploration of the potential of hermit crab essays within the traditional Japanese form known as the haibun, where prose and haiku work together.

A hermit crab essay is one that imitates a non-literary text—recipe, obituary, rejection letter—using the found form in novel ways, but retaining the semantic resonance of the original. Brenda Miller, who with Suzanne Paola coined the term in 2003, said that one of the benefits of working with these restrictions is creative expansion.

What is a Hermit Crab Essay? •Term coined in Brenda Miller and Suzanne Paola's Tell it Slant: Writing and Shaping Creative Nonfiction •A form-precedes-content technique for writing •Uses a recognizable form (along with its conventions) as a kind of shell for the nonfiction content (often memoir)

Hermit crab essays adopt already existing forms as the container for the writing at hand, such as the essay in the form of a "to-do" list, or a field guide, or a recipe. Hermit crabs are creatures born without their own shells to protect them; they need to find empty shells to inhabit (or sometimes not so empty; in the years since I've ...

The Essay as Bouquet. "Hermit crab" essays can take many forms, both natural and not. Ambrose Bierce, the American editorialist and journalist, wrote in his 1909 craft book, Write It Right, that "good writing" is "clear thinking made visible," an idea that has been repeated and adapted by countless writers over the past century.

By the end of the class, students will have generated the first draft of a hermit crab essay and have the opportunity to gain feedback from teacher and peers about how they might move their essay forward. This workshop will be held online. Saturday, October 15, 9:30 a.m. - 12:30 p.m. ($75) Register. For seven years, was a lecturer in first ...

A Hermit Crab essay is when an author inhabits an existing form in order to tell their own personal narrative. You may borrow structure from anything you can think of- from a prescription bottle label to a family recipe. Sit down with your journal- you'll never write anything you love if you don't write anything. Open the tab for ...

Like the hermit crab, this style of personal essay assumes a borrowed (and often unexpected) form as an outer shell. The narrative's rich insides are encased and revealed through a different structure. There are limitless possibilities, such as obituaries, recipes, questionnaires, manuals, or ads. In this course, we'll read and discuss ...