- Open access

- Published: 26 November 2021

Women’s Perceptions and Experiences of Breastfeeding: a scoping review of the literature

- Bridget Beggs 1 ,

- Liza Koshy 1 &

- Elena Neiterman 1

BMC Public Health volume 21 , Article number: 2169 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

15k Accesses

32 Citations

5 Altmetric

Metrics details

Despite public health efforts to promote breastfeeding, global rates of breastfeeding continue to trail behind the goals identified by the World Health Organization. While the literature exploring breastfeeding beliefs and practices is growing, it offers various and sometimes conflicting explanations regarding women’s attitudes towards and experiences of breastfeeding. This research explores existing empirical literature regarding women’s perceptions about and experiences with breastfeeding. The overall goal of this research is to identify what barriers mothers face when attempting to breastfeed and what supports they need to guide their breastfeeding choices.

This paper uses a scoping review methodology developed by Arksey and O’Malley. PubMed, CINAHL, Sociological Abstracts, and PsychInfo databases were searched utilizing a predetermined string of keywords. After removing duplicates, papers published in 2010–2020 in English were screened for eligibility. A literature extraction tool and thematic analysis were used to code and analyze the data.

In total, 59 papers were included in the review. Thematic analysis showed that mothers tend to assume that breastfeeding will be easy and find it difficult to cope with breastfeeding challenges. A lack of partner support and social networks, as well as advice from health care professionals, play critical roles in women’s decision to breastfeed.

While breastfeeding mothers are generally aware of the benefits of breastfeeding, they experience barriers at individual, interpersonal, and organizational levels. It is important to acknowledge that breastfeeding is associated with challenges and provide adequate supports for mothers so that their experiences can be improved, and breastfeeding rates can reach those identified by the World Health Organization.

Peer Review reports

Public health efforts to educate parents about the importance of breastfeeding can be dated back to the early twentieth century [ 1 ]. The World Health Organization is aiming to have at least half of all the mothers worldwide exclusively breastfeeding their infants in the first 6 months of life by the year 2025 [ 2 ], but it is unlikely that this goal will be achieved. Only 38% of the global infant population is exclusively breastfed between 0 and 6 months of life [ 2 ], even though breastfeeding initiation rates have shown steady growth globally [ 3 ]. The literature suggests that while many mothers intend to breastfeed and even make an attempt at initiation, they do not always maintain exclusive breastfeeding for the first 6 months of life [ 4 , 5 ]. The literature identifies various barriers, including return to paid employment [ 6 , 7 ], lack of support from health care providers and significant others [ 8 , 9 ], and physical challenges [ 9 ] as potential factors that can explain premature cessation of breastfeeding.

From a public health perspective, the health benefits of breastfeeding are paramount for both mother and infant [ 10 , 11 ]. Globally, new mothers following breastfeeding recommendations could prevent 974,956 cases of childhood obesity, 27,069 cases of mortality from breast cancer, and 13,644 deaths from ovarian cancer per year [ 11 ]. Global economic loss due to cognitive deficiencies resulting from cessation of breastfeeding has been calculated to be approximately USD $285.39 billion dollars annually [ 11 ]. Evidently, increasing exclusive breastfeeding rates is an important task for improving population health outcomes. While public health campaigns targeting pregnant women and new mothers have been successful in promoting breastfeeding, they also have been perceived as too aggressive [ 12 ] and failing to consider various structural and personal barriers that may impact women’s ability to breastfeed [ 1 ]. In some cases, public health messaging itself has been identified as a barrier due to its rigid nature and its lack of flexibility in guidelines [ 13 ]. Hence, while the literature on women’s perceptions regarding breastfeeding and their experiences with breastfeeding has been growing [ 14 , 15 , 16 ], it offers various, and sometimes contradictory, explanations on how and why women initiate and maintain breastfeeding and what role public health messaging plays in women’s decision to breastfeed.

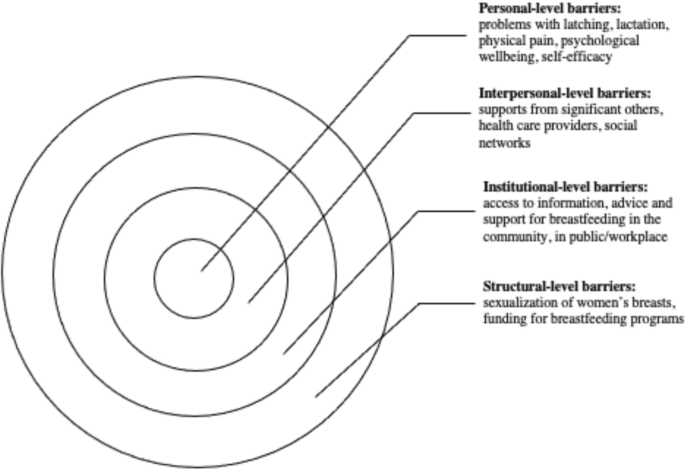

The complex array of the barriers shaping women’s experiences of breastfeeding can be broadly categorized utilizing the socioecological model, which suggests that individuals’ health is a result of the interplay between micro (individual), meso (institutional), and macro (social) factors [ 17 ]. Although previous studies have explored barriers and supports to breastfeeding, the majority of articles focus on specific geographic areas (e.g. United States or United Kingdom), workplaces, or communities. In addition, very few articles focus on the analysis of the interplay between various micro, meso, and macro-level factors in shaping women’s experiences of breastfeeding. Synthesizing the growing literature on the experiences of breastfeeding and the factors shaping these experiences, offers researchers and public health professionals an opportunity to examine how various personal and institutional factors shape mothers’ breastfeeding decision-making. This knowledge is needed to identify what can be done to improve breastfeeding rates and make breastfeeding a more positive and meaningful experience for new mothers.

The aim of this scoping review is to synthesize evidence gathered from empirical literature on women’s perceptions about and experiences of breastfeeding. Specifically, the following questions are examined:

What does empirical literature report on women’s perceptions on breastfeeding?

What barriers do women face when they attempt to initiate or maintain breastfeeding?

What supports do women need in order to initiate and/or maintain breastfeeding?

Focusing on women’s experiences, this paper aims to contribute to our understanding of women’s decision-making and behaviours pertaining to breastfeeding. The overarching aim of this review is to translate these findings into actionable strategies that can streamline public health messaging and improve breastfeeding education and supports offered by health care providers working with new mothers.

This research utilized Arksey & O’Malley’s [ 18 ] framework to guide the scoping review process. The scoping review methodology was chosen to explore a breadth of literature on women’s perceptions about and experiences of breastfeeding. A broad research question, “What does empirical literature tell us about women’s experiences of breastfeeding?” was set to guide the literature search process.

Search methods

The review was undertaken in five steps: (1) identifying the research question, (2) identifying relevant literature, (3) iterative selection of data, (4) charting data, and (5) collating, summarizing, and reporting results. The inclusion criteria were set to empirical articles published between 2010 and 2020 in peer-reviewed journals with a specific focus on women’s self-reported experiences of breastfeeding, as well as how others see women’s experiences of breastfeeding. The focus on women’s perceptions of breastfeeding was used to capture the papers that specifically addressed their experiences and the barriers that they may encounter while breastfeeding. Only articles written in English were included in the review. The keywords utilized in the search strategy were developed in collaboration with a librarian (Table 1 ). PubMed, CINAHL, Sociological Abstracts, and PsychInfo databases were searched for the empirical literature, yielding a total of 2885 results.

Search outcome

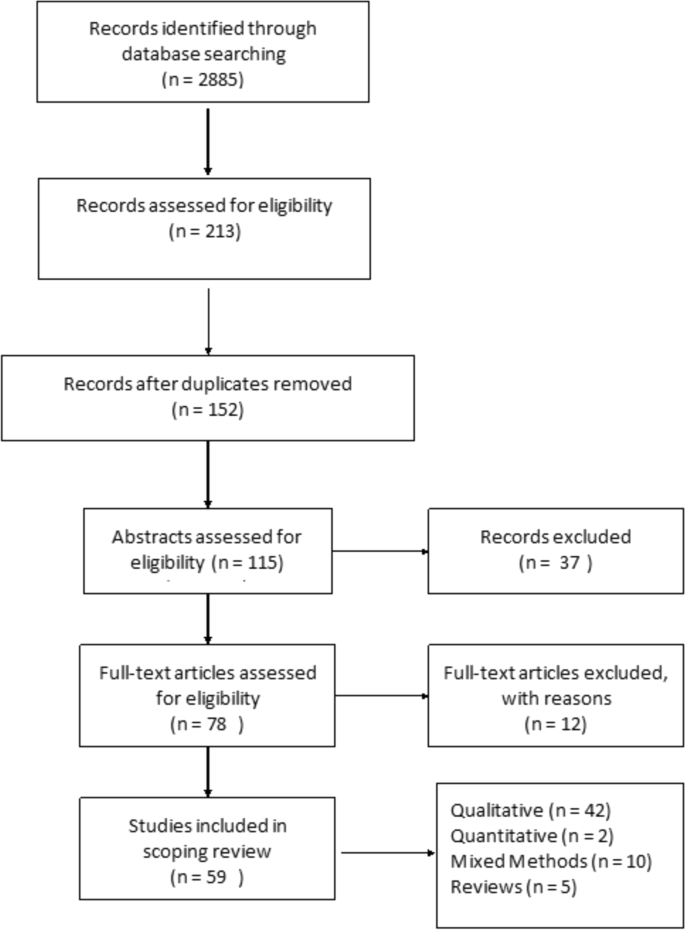

The articles deemed to fit the inclusion criteria ( n = 213) were imported into RefWorks, an online reference manager tool and further screened for eligibility (Fig. 1 ). After the removal of 61 duplicates and title/abstract screening, 152 articles were kept for full-text review. Two independent reviewers assessed the papers to evaluate if they met the inclusion criteria of having an explicit analytic focus on women’s experiences of breastfeeding.

Prisma Flow Diagram

Quality appraisal

Consistent with scoping review methodology [ 18 ], the quality of the papers included in the review was not assessed.

Data abstraction

A literature extraction tool was created in MS Excel 2016. The data extracted from each paper included: (a) authors names, (b) title of the paper, (c) year of publication, (d) study objectives, (e) method used, (f) participant demographics, (g) country where the study was conducted, and (h) key findings from the paper.

Thematic analysis was utilized to identify key topics covered by the literature. Two reviewers independently read five papers to inductively generate key themes. This process was repeated until the two reviewers reached a consensus on the coding scheme, which was subsequently applied to the remainder of the articles. Key themes were added to the literature extraction tool and each paper was assigned a key theme and sub-themes, if relevant. The themes derived from the analysis were reviewed once again by all three authors when all the papers were coded. In the results section below, the synthesized literature is summarized alongside the key themes identified during the analysis.

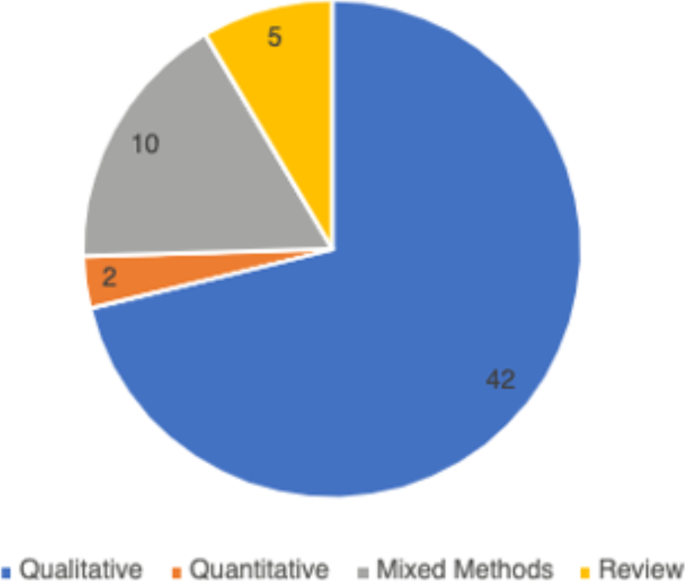

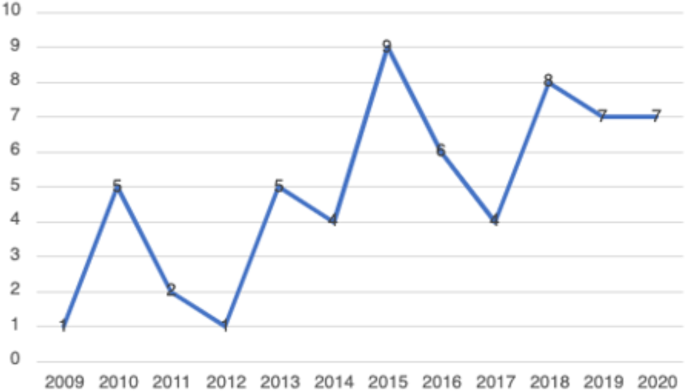

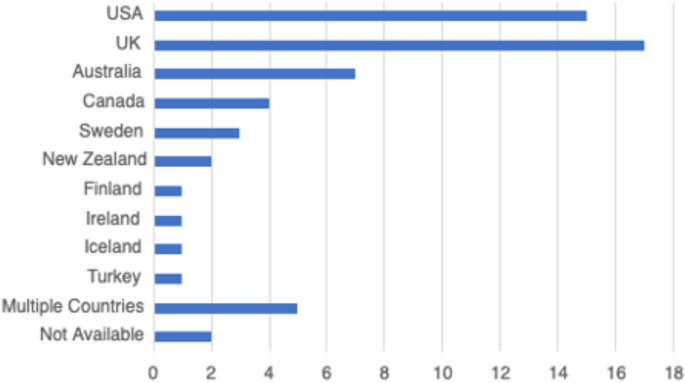

In total, 59 peer-reviewed articles were included in the review. Since the review focused on women’s experiences of breastfeeding, as would be expected based on the search criteria, the majority of articles ( n = 42) included in the sample were qualitative studies, with ten utilizing a mixed method approach (Fig. 2 ). Figure 3 summarizes the distribution of articles by year of publication and Fig. 4 summarizes the geographic location of the study.

Types of Articles

Years of Publication

Countries of Focus Examined in Literature Review

Perceptions about breastfeeding

Women’s perceptions about breastfeeding were covered in 83% ( n = 49) of the papers. Most articles ( n = 31) suggested that women perceived breastfeeding as a positive experience and believed that breastfeeding had many benefits [ 19 , 20 ]. The phrases “breast is best” and “breastmilk is best” were repeatedly used by the participants of studies included in the reviewed literature [ 21 ]. Breastfeeding was seen as improving the emotional bond between the mother and the child [ 20 , 22 , 23 ], strengthening the child’s immune system [ 24 , 25 ], and providing a booster to the mother’s sense of self [ 1 , 26 ]. Convenience of breastfeeding (e.g., its availability and low cost) [ 19 , 27 ] and the role of breastfeeding in weight loss during the postpartum period were mentioned in the literature as other factors that positively shape mothers’ perceptions about breastfeeding [ 28 , 29 ].

The literature suggested that women’s perceptions of breastfeeding and feeding choices were also shaped by the advice of healthcare providers [ 30 , 31 ]. Paradoxically, messages about the importance and relative simplicity of breastfeeding may also contribute to misalignment between women’s expectations and the actual experiences of breastfeeding [ 32 ]. For instance, studies published in Canada and Sweden reported that women expected breastfeeding to occur “naturally”, to be easy and enjoyable [ 23 ]. Consequently, some women felt unprepared for the challenges associated with initiation or maintenance of breastfeeding [ 31 , 33 ]. The literature pointed out that mothers may feel overwhelmed by the frequency of infant feedings [ 26 ] and the amount as well as intensity of physical difficulties associated with breastfeeding initiation [ 33 ]. Researchers suggested that since many women see breastfeeding as a sign of being a “good” mother, their inability to breastfeed may trigger feelings of personal failure [ 22 , 34 ].

Women’s personal experiences with and perceptions about breastfeeding were also influenced by the cultural pressure to breastfeed. Welsh mothers interviewed in the UK, for instance, revealed that they were faced with judgement and disapproval when people around them discovered they opted out of breastfeeding [ 35 ]. Women recalled the experiences of being questioned by others, including strangers, when they were bottle feeding their infants [ 9 , 35 , 36 ].

Barriers to breastfeeding

The vast majority ( n = 50) of the reviewed literature identified various barriers for successful breastfeeding. A sizeable proportion of literature (41%, n = 24) explored women’s experiences with the physical aspects of breastfeeding [ 23 , 33 ]. In particular, problems with latching and the pain associated with breastfeeding were commonly cited as barriers for women to initiate breastfeeding [ 23 , 28 , 37 ]. Inadequate milk supply, both actual and perceived, was mentioned as another barrier for initiation and maintenance of breastfeeding [ 33 , 37 ]. Breastfeeding mothers were sometimes unable to determine how much milk their infants consumed (as opposed to seeing how much milk the infant had when bottle feeding), which caused them to feel anxious and uncertain about scheduling infant feedings [ 28 , 37 ]. Women’s inability to overcome these barriers was linked by some researchers to low self-efficacy among mothers, as well as feeling overwhelmed or suffering from postpartum depression [ 38 , 39 ].

In addition to personal and physical challenges experienced by mothers who were planning to breastfeed, the literature also highlighted the importance of social environment as a potential barrier to breastfeeding. Mothers’ personal networks were identified as a key factor in shaping their breastfeeding behaviours in 43 (73%) articles included in this review. In a study published in the UK, lack of role models – mothers, other female relatives, and friends who breastfeed – was cited as one of the potential barriers for breastfeeding [ 36 ]. Some family members and friends also actively discouraged breastfeeding, while openly questioning the benefits of this practice over bottle feeding [ 1 , 17 , 40 ]. Breastfeeding during family gatherings or in the presence of others was also reported as a challenge for some women from ethnic minority groups in the United Kingdom and for Black women in the United States [ 41 , 42 ].

The literature reported occasional instances where breastfeeding-related decisions created conflict in women’s relationships with significant others [ 26 ]. Some women noted they were pressured by their loved one to cease breastfeeding [ 22 ], especially when women continued to breastfeed 6 months postpartum [ 43 ]. Overall, the literature suggested that partners play a central role in women’s breastfeeding practices [ 8 ], although there was no consistency in the reviewed papers regarding the partners’ expressed level of support for breastfeeding.

Knowledge, especially practical knowledge about breastfeeding, was mentioned as a barrier in 17% ( n = 10) of the papers included in this review. While health care providers were perceived as a primary source of information on breastfeeding, some studies reported that mothers felt the information provided was not useful and occasionally contained conflicting advice [ 1 , 17 ]. This finding was reported across various jurisdictions, including the United States, Sweden, the United Kingdom and Netherlands, where mothers reported they had no support at all from their health care providers which made it challenging to address breastfeeding problems [ 26 , 38 , 44 ].

Breastfeeding in public emerged as a key barrier from the reviewed literature and was cited in 56% ( n = 33) of the papers. Examining the experiences of breastfeeding mothers in the United States, Spencer, Wambach, & Domain [ 45 ] suggested that some participants reported feeling “erased” from conversations while breastfeeding in public, rendering their bodies symbolically invisible. Lack of designated public spaces for breastfeeding forced many women to alter their feeding in public and to retreat to a private or a more secluded space, such as one’s personal car [ 25 ]. The oversexualization of women’s breasts was repeatedly noted as a core reason for the United States women’s negative experiences and feelings of self-consciousness about breastfeeding in front of others [ 45 ]. Studies reported women’s accounts of feeling the disapproval or disgust of others when breastfeeding in public [ 46 , 47 ], and some reported that women opted out of breastfeeding in public because they did not want to make those around them feel uncomfortable [ 25 , 40 , 48 ].

Finally, return to paid employment was noted in the literature as a significant challenge for continuation of breastfeeding [ 48 ]. Lack of supportive workplace environments [ 39 ] or inability to express milk were cited by women as barriers for continuing breastfeeding in the United States and New Zealand [ 39 , 49 ].

Supports needed to maintain breastfeeding

Due to the central role family members played in women’s experiences of breastfeeding, support from partners as well as female relatives was cited in the literature as key factors shaping women’s breastfeeding decisions [ 1 , 9 , 48 ]. In the articles published in Canada, Australia, and the United Kingdom, supportive family members allowed women to share the responsibility of feeding and other childcare activities, which reduced the pressures associated with being a new mother [ 19 , 20 ]. Similarly, encouragement, breastfeeding advice, and validation from healthcare professionals were identified as positively impacting women’s experiences with breastfeeding [ 1 , 22 , 28 ].

Community resources, such as peer support groups, helplines, and in-home breastfeeding support provided mothers with the opportunity to access help when they need it, and hence were reported to be facilitators for breastfeeding [ 19 , 22 , 33 , 44 ]. An increase in the usage of social media platforms, such as Facebook, among breastfeeding mothers for peer support were reported in some studies [ 47 ]. Public health breastfeeding clinics, lactation specialists, antenatal and prenatal classes, as well as education groups for mothers were identified as central support structures for the initiation and maintenance of breastfeeding [ 23 , 24 , 28 , 33 , 39 , 50 ]. Based on the analysis of the reviewed literature, however, access to these services varied greatly geographically and by socio-economic status [ 33 , 51 ]. It is also important to note that local and cultural context played a significant role in shaping women’s perceptions of breastfeeding. For example, a study that explored women’s breastfeeding experiences in Iceland highlighted the importance of breastfeeding in Icelandic society [ 52 ]. Women are expected to breastfeed and the decision to forgo breastfeeding is met with disproval [ 52 ]. Cultural beliefs regarding breastfeeding were also deemed important in the study of Szafrankska and Gallagher (2016), who noted that Polish women living in Ireland had a much higher rate of initiating breastfeeding compared to Irish women [ 53 ]. They attributed these differences to familial and societal expectations regarding breastfeeding in Poland [ 53 ].

Overall, the reviewed literature suggested that women faced socio-cultural pressure to breastfeed their infants [ 36 , 40 , 54 ]. Women reported initiating breastfeeding due to recognition of the many benefits it brings to the health of the child, even when they were reluctant to do it for personal reasons [ 8 ]. This hints at the success of public health education campaigns on the benefits of breastfeeding, which situates breastfeeding as a new cultural norm [ 24 ].

This scoping review examined the existing empirical literature on women’s perceptions about and experiences of breastfeeding to identify how public health messaging can be tailored to improve breastfeeding rates. The literature suggests that, overall, mothers are aware of the positive impacts of breastfeeding and have strong motivation to breastfeed [ 37 ]. However, women who chose to breastfeed also experience many barriers related to their social interactions with significant others and their unique socio-cultural contexts [ 25 ]. These different factors, summarized in Fig. 5 , should be considered in developing public health activities that promote breastfeeding. Breastfeeding experiences for women were very similar across the United Kingdom, United States, Canada, and Australia based on the studies included in this review. Likewise, barriers and supports to breastfeeding identified by women across the countries situated in the global north were quite similar. However, local policy context also impacted women’s experiences of breastfeeding. For example, maintaining breastfeeding while returning to paid employment has been identified as a challenge for mothers in the United States [ 39 , 45 ], a country with relatively short paid parental leave. Still, challenges with balancing breastfeeding while returning to paid employment were also noticed among women in New Zealand, despite a more generous maternity leave [ 49 ]. This suggests that while local and institutional policies might shape women’s experiences of breastfeeding, interpersonal and personal factors can also play a central role in how long they breastfeed their infants. Evidently, the importance of significant others, such as family members or friends, in providing support to breastfeeding mothers was cited as a key facilitator for breastfeeding across multiple geographic locations [ 29 , 34 , 48 ]. In addition, cultural beliefs and practices were also cited as an important component in either promoting breastfeeding or deterring women’s desire to initiate or maintain breastfeeding [ 15 , 29 , 37 ]. Societal support for breastfeeding and cultural practices can therefore partly explain the variation in breastfeeding rates across different countries [ 15 , 21 ]. Figure 5 summarizes the key barriers identified in the literature that inhibit women’s ability to breastfeed.

Barriers to Breastfeeding

At the individual level, women might experience challenges with breastfeeding stemming from various physiological and psychological problems, such as issues with latching, perceived or actual lack of breastmilk, and physical pain associated with breastfeeding. The onset of postpartum depression or other psychological problems may also impact women’s ability to breastfeed [ 54 ]. Given that many women assume that breastfeeding will happen “naturally” [ 15 , 40 ] these challenges can deter women from initiating or continuing breastfeeding. In light of these personal challenges, it is important to consider the potential challenges associated with breastfeeding that are conveyed to new mothers through the simplified message “breast is best” [ 21 ]. While breastfeeding may come easy to some women, most papers included in this review pointed to various challenges associated with initiating or maintaining breastfeeding [ 19 , 33 ]. By modifying public health messaging regarding breastfeeding to acknowledge that breastfeeding may pose a challenge and offering supports to new mothers, it might be possible to alleviate some of the guilt mothers experience when they are unable to breastfeed.

Barriers that can be experienced at the interpersonal level concern women’s communication with others regarding their breastfeeding choices and practices. The reviewed literature shows a strong impact of women’s social networks on their decision to breastfeed [ 24 , 33 ]. In particular, significant others – partners, mothers, siblings and close friends – seem to have a considerable influence over mothers’ decision to breastfeed [ 42 , 53 , 55 ]. Hence, public health messaging should target not only mothers, but also their significant others in developing breastfeeding campaigns. Social media may also be a potential medium for sharing supports and information regarding breastfeeding with new mothers and their significant others.

There is also a strong need for breastfeeding supports at the institutional and community levels. Access to lactation consultants, sound and practical advice from health care providers, and availability of physical spaces in the community and (for women who return to paid employment) in the workplace can provide more opportunities for mothers who want to breastfeed [ 18 , 33 , 44 ]. The findings from this review show, however, that access to these supports and resources vary greatly, and often the women who need them the most lack access to them [ 56 ].

While women make decisions about breastfeeding in light of their own personal circumstances, it is important to note that these circumstances are shaped by larger structural, social, and cultural factors. For instance, mothers may feel reluctant to breastfeed in public, which may stem from their familiarity with dominant cultural perspectives that label breasts as objects for sexualized pleasure [ 48 ]. The reviewed literature also showed that, despite the initial support, mothers who continue to breastfeed past the first year may be judged and scrutinized by others [ 47 ]. Tailoring public health care messaging to local communities with their own unique breastfeeding-related beliefs might help to create a larger social change in sociocultural norms regarding breastfeeding practices.

The literature included in this scoping review identified the importance of support from community services and health care providers in facilitating women’s breastfeeding behaviours [ 22 , 24 ]. Unfortunately, some mothers felt that the support and information they received was inadequate, impractical, or infused with conflicting messaging [ 28 , 44 ]. To make breastfeeding support more accessible to women across different social positions and geographic locations, it is important to acknowledge the need for the development of formal infrastructure that promotes breastfeeding. This includes training health care providers to help women struggling with breastfeeding and allocating sufficient funding for such initiatives.

Overall, this scoping review revealed the need for healthcare professionals to provide practical breastfeeding advice and realistic solutions to women encountering difficulties with breastfeeding. Public health messaging surrounding breastfeeding must re-invent breastfeeding as a “family practice” that requires collaboration between the breastfeeding mother, their partner, as well as extended family to ensure that women are supported as they breastfeed [ 8 ]. The literature also highlighted the issue of healthcare professionals easily giving up on women who encounter problems with breastfeeding and automatically recommending the initiation of formula use without further consideration towards solutions for breastfeeding difficulties [ 19 ]. While some challenges associated with breastfeeding are informed by local culture or health care policies, most of the barriers experienced by breastfeeding women are remarkably universal. Women often struggle with initiation of breastfeeding, lack of support from their significant others, and lack of appropriate places and spaces to breastfeed [ 25 , 26 , 33 , 39 ]. A change in public health messaging to a more flexible messaging that recognizes the challenges of breastfeeding is needed to help women overcome negative feelings associated with failure to breastfeed. Offering more personalized advice and support to breastfeeding mothers can improve women’s experiences and increase the rates of breastfeeding while also boosting mothers’ sense of self-efficacy.

Limitations

This scoping review has several limitations. First, the focus on “women’s experiences” rendered broad search criteria but may have resulted in the over or underrepresentation of specific findings in this review. Also, the exclusion of empirical work published in languages other than English rendered this review reliant on the papers published predominantly in English-speaking countries. Finally, consistent with Arksey and O’Malley’s [ 18 ] scoping review methodology, we did not appraise the quality of the reviewed literature. Notwithstanding these limitations, this review provides important insights into women’s experiences of breastfeeding and offers practical strategies for improving dominant public health messaging on the importance of breastfeeding.

Women who breastfeed encounter many difficulties when they initiate breastfeeding, and most women are unsuccessful in adhering to current public health breastfeeding guidelines. This scoping review highlighted the need for reconfiguring public health messaging to acknowledge the challenges many women experience with breastfeeding and include women’s social networks as a target audience for such messaging. This review also shows that breastfeeding supports and counselling are needed by all women, but there is also a need to tailor public health messaging to local social norms and culture. The role social institutions and cultural discourses have on women’s experiences of breastfeeding must also be acknowledged and leveraged by health care professionals promoting breastfeeding.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

Wolf JH. Low breastfeeding rates and public health in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(12):2000–2010. [cited 2021 Apr 21] Available from: http://ajph.aphapublications.org/doi/ https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.93.12.2000

World Health Organization, UNICEF. Global nutrition targets 2015: Breastfeeding policy brief 2014.

United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF). Breastfeeding in the UK. 2019 [cited 2021 Apr 21]. Available from: https://www.unicef.org.uk/babyfriendly/about/breastfeeding-in-the-uk/

Semenic S, Loiselle C, Gottlieb L. Predictors of the duration of exclusive breastfeeding among first-time mothers. Res Nurs Health. 2008;31(5):428–441. [cited 2021 Apr 21] Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/ https://doi.org/10.1002/nur.20275

Hauck YL, Bradfield Z, Kuliukas L. Women’s experiences with breastfeeding in public: an integrative review. Women Birth. 2020;34:e217–27.

Hendaus MA, Alhammadi AH, Khan S, Osman S, Hamad A. Breastfeeding rates and barriers: a report from the state of Qatar. Int. J Women's Health. 2018;10:467–75 [cited 2021 Apr 20] Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC6110662/.

Google Scholar

Ogbo FA, Ezeh OK, Khanlari S, Naz S, Senanayake P, Ahmed KY, et al. Determinants of exclusive breastfeeding cessation in the early postnatal period among culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) Australian mothers. Nutrients. 2019;11(7):1611 [cited 2021 Apr 21] Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2072-6643/11/7/1611 .

Article Google Scholar

Ayton JE, Tesch L, Hansen E. Women’s experiences of ceasing to breastfeed: Australian qualitative study. BMJ Open. 2019;9(5):26234 [cited 2021 Apr 20] Available from: http://bmjopen.bmj.com/ .

Brown CRL, Dodds L, Legge A, Bryanton J, Semenic S. Factors influencing the reasons why mothers stop breastfeeding. Can J Public Heal. 2014;105(3):e179–e185. [cited 2021 Apr 20] Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/ https://doi.org/10.17269/cjph.105.4244

Sharma AJ, Dee DL, Harden SM. Adherence to breastfeeding guidelines and maternal weight 6 years after delivery. Pediatrics. 2014;134(Supplement 1):S42–S49. [cited 2021 Apr 21] Available from: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/doi/ https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2014-0646H

Walters DD, Phan LTH, Mathisen R. The cost of not breastfeeding: Global results from a new tool. Health Policy Plan. 2019;34(6):407–17 [cited 2021 Apr 21] Available from: https://academic.oup.com/heapol/article/34/6/407/5522499 .

Friedman M. For whom is breast best? Thoughts on breastfeeding, feminism and ambivalence. J Mother Initiat Res Community Involv. 2009;11(1):26–35 [cited 2021 Apr 20] Available from: https://jarm.journals.yorku.ca/index.php/jarm/article/viewFile/22506/20986 .

Blixt I, Johansson M, Hildingsson I, Papoutsi Z, Rubertsson C. Women’s advice to healthcare professionals regarding breastfeeding: “offer sensitive individualized breastfeeding support” - an interview study. Int Breastfeed J 2019;14(1):51. [cited 2021 Apr 20] Available from: https://internationalbreastfeedingjournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13006-019-0247-4

Obeng C, Dickinson S, Golzarri-Arroyo L. Women’s perceptions about breastfeeding: a preliminary study. Children. 2020;7(6):61 [cited 2021 Apr 21] Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2227-9067/7/6/61 .

Choudhry K, Wallace LM. ‘Breast is not always best’: South Asian women’s experiences of infant feeding in the UK within an acculturation framework. Matern Child Nutr. 2012;8(1):72–87. [cited 2021 Apr 20] Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/ https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1740-8709.2010.00253.x

Da Silva TD, Bick D, Chang YS. Breastfeeding experiences and perspectives among women with postnatal depression: a qualitative evidence synthesis. Women Birth. 2020;33(3):231–9.

Kilanowski JF. Breadth of the socio-ecological model. J Agromedicine. 2017;22(4):295–7 [cited 2021 Apr 20] Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=wagr20 .

Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol Theory Pract. 2005;8(1):19–32 [cited 2021 Apr 20] Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=tsrm20 .

Brown A, Lee M. An exploration of the attitudes and experiences of mothers in the United Kingdom who chose to breastfeed exclusively for 6 months postpartum. Breastfeed Med. 2011;6(4):197–204. [cited 2021 Apr 20] Available from: http://www.liebertpub.com/doi/ https://doi.org/10.1089/bfm.2010.0097

Morns MA, Steel AE, Burns E, McIntyre E. Women who experience feelings of aversion while breastfeeding: a meta-ethnographic review. Women Birth. 2021;34:128–35.

Jackson KT, Mantler T, O’Keefe-McCarthy S. Women’s experiences of breastfeeding-related pain. MCN Am J Matern Nurs. 2019;44(2):66–72 [cited 2021 Apr 20] Available from: https://journals.lww.com/00005721-201903000-00002 .

Burns E, Schmied V, Sheehan A, Fenwick J. A meta-ethnographic synthesis of women’s experience of breastfeeding. Matern Child Nutr. 2009;6(3):201–219. [cited 2021 Apr 20] Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/ https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1740-8709.2009.00209.x

Claesson IM, Larsson L, Steen L, Alehagen S. “You just need to leave the room when you breastfeed” Breastfeeding experiences among obese women in Sweden - A qualitative study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2018;18(1):1–10. [cited 2021 Apr 20] Available from: https://link.springer.com/articles/ https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-017-1656-2

Asiodu IV, Waters CM, Dailey DE, Lyndon • Audrey. Infant feeding decision-making and the influences of social support persons among first-time African American mothers. Matern Child Health J. 2017;21:863–72.

Forster DA, McLachlan HL. Women’s views and experiences of breast feeding: positive, negative or just good for the baby? Midwifery. 2010;26(1):116–25.

Demirci J, Caplan E, Murray N, Cohen S. “I just want to do everything right:” Primiparous Women’s accounts of early breastfeeding via an app-based diary. J Pediatr Heal Care. 2018;32(2):163–72.

Furman LM, Banks EC, North AB. Breastfeeding among high-risk Inner-City African-American mothers: a risky choice? Breastfeed Med. 2013;8(1):58–67. [cited 2021 Apr 20]Available from: http://www.liebertpub.com/doi/ https://doi.org/10.1089/bfm.2012.0012

Cottrell BH, Detman LA. Breastfeeding concerns and experiences of african american mothers. MCN Am J Matern Nurs. 2013;38(5):297–304 [cited 2021 Apr 20] Available from: https://journals.lww.com/00005721-201309000-00009 .

Wambach K, Domian EW, Page-Goertz S, Wurtz H, Hoffman K. Exclusive breastfeeding experiences among mexican american women. J Hum Lact. 2016;32(1):103–111. [cited 2021 Apr 21] Available from: http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/ https://doi.org/10.1177/0890334415599400

Regan P, Ball E. Breastfeeding mothers’ experiences: The ghost in the machine. Qual Health Res. 2013;23(5):679–688. [cited 2021 Apr 21] Available from: http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/ https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732313481641

Hinsliff-Smith K, Spencer R, Walsh D. Realities, difficulties, and outcomes for mothers choosing to breastfeed: Primigravid mothers experiences in the early postpartum period (6-8 weeks). Midwifery. 2014;30(1):e14–9.

Palmér L. Previous breastfeeding difficulties: an existential breastfeeding trauma with two intertwined pathways for future breastfeeding—fear and longing. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-being. 2019;14(1) [cited 2021 Apr 21] Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=zqhw20 .

Francis J, Mildon A, Stewart S, Underhill B, Tarasuk V, Di Ruggiero E, et al. Vulnerable mothers’ experiences breastfeeding with an enhanced community lactation support program. Matern Child Nutr 2020;16(3):16. [cited 2021 Apr 20] Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/ https://doi.org/10.1111/mcn.12957

Palmér L, Carlsson G, Mollberg M, Nyström M. Breastfeeding: An existential challenge - Women’s lived experiences of initiating breastfeeding within the context of early home discharge in Sweden. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-being 2010;5(3). [cited 2021 Apr 21] Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=zqhw20https://doi.org/ https://doi.org/10.3402/qhw.v5i3.5397

Grant A, Mannay D, Marzella R. ‘People try and police your behaviour’: the impact of surveillance on mothers and grandmothers’ perceptions and experiences of infant feeding. Fam Relationships Soc. 2018;7(3):431–47.

Thomson G, Ebisch-Burton K, Flacking R. Shame if you do - shame if you don’t: women’s experiences of infant feeding. Matern Child Nutr. 2015;11(1):33–46. [cited 2021 Apr 21] Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/ https://doi.org/10.1111/mcn.12148

Dietrich Leurer M, Misskey E. The psychosocial and emotional experience of breastfeeding: reflections of mothers. Glob Qual. Nurs Res. 2015;2:2333393615611654 [cited 2021 Apr 20] Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28462320 .

Fahlquist JN. Experience of non-breastfeeding mothers: Norms and ethically responsible risk communication. Nurs Ethics. 2016;23(2):231–241. [cited 2021 Apr 20] Available from: http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/ https://doi.org/10.1177/0969733014561913

Gross TT, Davis M, Anderson AK, Hall J, Hilyard K. Long-term breastfeeding in African American mothers: a positive deviance inquiry of WIC participants. J Hum Lact. 2017;33(1):128–139. [cited 2021 Apr 20] Available from: http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/ https://doi.org/10.1177/0890334416680180

Spencer RL, Greatrex-White S, Fraser DM. ‘I thought it would keep them all quiet’. Women’s experiences of breastfeeding as illusions of compliance: an interpretive phenomenological study. J Adv Nurs. 2015;71(5):1076–1086. [cited 2021 Apr 21] Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/ https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.12592

Twamley K, Puthussery S, Harding S, Baron M, Macfarlane A. UK-born ethnic minority women and their experiences of feeding their newborn infant. Midwifery. 2011;27(5):595–602.

PubMed Google Scholar

Lutenbacher M, Karp SM, Moore ER. Reflections of Black women who choose to breastfeed: influences, challenges, and supports. Matern Child Health J. 2016;20(2):231–9.

Dowling S, Brown A. An exploration of the experiences of mothers who breastfeed long-term: what are the issues and why does it matter? Breastfeed Med. 2013;8(1):45–52. [cited 2021 Apr 20] Available from: http://www.liebertpub.com/doi/ https://doi.org/10.1089/bfm.2012.0057

Fox R, McMullen S, Newburn M. UK women’s experiences of breastfeeding and additional breastfeeding support: a qualitative study of baby Café services. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2015;15(1):147. [cited 2021 Apr 20] Available from: http://bmcpregnancychildbirth.biomedcentral.com/articles/ https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-015-0581-5

Spencer B, Wambach K, Domain EW. African American women’s breastfeeding experiences: cultural, personal, and political voices. Qual Health Res. 2015;25(7):974–987. [cited 2021 Apr 21] Available from: http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/ https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732314554097

McBride-Henry K. The influence of the They: An interpretation of breastfeeding culture in New Zealand. Qual Health Res. 2010;20(6):768–777. [cited 2021 Apr 21] Available from: http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/ https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732310364220

Newman KL, Williamson IR. Why aren’t you stopping now?!’ Exploring accounts of white women breastfeeding beyond six months in the east of England. Appetite. 2018 Oct;1(129):228–35.

Dowling S, Pontin D. Using liminality to understand mothers’ experiences of long-term breastfeeding: ‘Betwixt and between’, and ‘matter out of place.’ Heal (United Kingdom). 2017;21(1):57–75. [cited 2021 Apr 20] Available from: http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/ https://doi.org/10.1177/1363459315595846

Payne D, Nicholls DA. Managing breastfeeding and work: a Foucauldian secondary analysis. J Adv Nurs. 2010;66(8):1810–1818. [cited 2021 Apr 21] Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/ https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2009.05156.x

Keely A, Lawton J, Swanson V, Denison FC. Barriers to breast-feeding in obese women: a qualitative exploration. Midwifery. 2015;31(5):532–9.

Afoakwah G, Smyth R, Lavender DT. Women’s experiences of breastfeeding: A narrative review of qualitative studies. Afr J Midwifery Womens Health. 2013 ;7(2):71–77. [cited 2021 Apr 21] Available from: https://www.magonlinelibrary.com/doi/abs/ https://doi.org/10.12968/ajmw.2013.7.2.71

Símonardóttir S. Getting the green light: experiences of Icelandic mothers struggling with breastfeeding. Sociol Res Online. 2016;21(4):1.

Szafranska M, Gallagher DL. Polish women’s experiences of breastfeeding in Ireland. Pract Midwife. 2016;19(1):30–2 [cited 2021 Apr 21] Available from: https://europepmc.org/article/med/26975131 .

Pratt BA, Longo J, Gordon SC, Jones NA. Perceptions of breastfeeding for women with perinatal depression: a descriptive phenomenological study. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2020;41(7):637–644. [cited 2021 Apr 21] Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/ https://doi.org/10.1080/01612840.2019.1691690

Durmazoğlu G, Yenal K, Okumuş H. Maternal emotions and experiences of mothers who had breastfeeding problems: a qualitative study. Res Theory Nurs Pract. 2020;34(1):3–20. [cited 2021 Apr 20] Available from: http://connect.springerpub.com/lookup/doi/ https://doi.org/10.1891/1541-6577.34.1.3

Burns E, Triandafilidis Z. Taking the path of least resistance: a qualitative analysis of return to work or study while breastfeeding. Int Breastfeed J. 2019;14(1):1–13.

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the assistance of Jackie Stapleton, the University of Waterloo librarian, for her assistance with developing the search strategy used in this review.

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

School of Public Health Sciences, University of Waterloo, 200 University Ave West, Waterloo, ON, N2L 3G1, Canada

Bridget Beggs, Liza Koshy & Elena Neiterman

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

BB was responsible for the formal analysis and organization of the review. LK was responsible for data curation, visualization and writing the original draft. EN was responsible for initial conceptualization and writing the original draft. BB and LK were responsible for reviewing and editing the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ information

BB is completing her Bachelor of Science (BSc) degree at the School of Public Health Sciences at the University of Waterloo.

LK is completing her Bachelor of Public Health (BPH) degree at the School of Public Health Sciences at the University of Waterloo.

EN (PhD), is a continuing lecturer at the School of Public Health Sciences at the University of Waterloo. Her areas of expertise are in women’s reproductive health and sociology of health, illness, and healthcare.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Bridget Beggs .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate, consent for publication, competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Beggs, B., Koshy, L. & Neiterman, E. Women’s Perceptions and Experiences of Breastfeeding: a scoping review of the literature. BMC Public Health 21 , 2169 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-12216-3

Download citation

Received : 23 June 2021

Accepted : 10 November 2021

Published : 26 November 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-12216-3

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Breastfeeding

- Experiences

- Public health

BMC Public Health

ISSN: 1471-2458

- General enquiries: [email protected]

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Breastfeeding and maternal health outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis

Ranadip chowdhury, bireshwar sinha, mari jeeva sankar, sunita taneja, nita bhandari, nigel rollins, jose martines.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Dr Ranadip Chowdhury, Scientist, Centre for Health Research and Development, Society for Applied Studies, 45, Kalu Sarai, New Delhi-110016, India. Tel: +91 011 46043751- 55 | Fax: +91 011 46043756 | Email: [email protected]

Received 2015 May 18; Revised 2015 Jun 16; Accepted 2015 Jun 18; Issue date 2015 Dec.

This is an open access article under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

To evaluate the effect of breastfeeding on long-term (breast carcinoma, ovarian carcinoma, osteoporosis and type 2 diabetes mellitus) and short-term (lactational amenorrhoea, postpartum depression, postpartum weight change) maternal health outcomes.

A systematic literature search was conducted in PubMed, Cochrane Library and CABI databases. Outcome estimates of odds ratios or relative risks or standardised mean differences were pooled. In cases of heterogeneity, subgroup analysis and meta-regression were explored.

Breastfeeding >12 months was associated with reduced risk of breast and ovarian carcinoma by 26% and 37%, respectively. No conclusive evidence of an association between breastfeeding and bone mineral density was found. Breastfeeding was associated with 32% lower risk of type 2 diabetes. Exclusive breastfeeding and predominant breastfeeding were associated with longer duration of amenorrhoea. Shorter duration of breastfeeding was associated with higher risk of postpartum depression. Evidence suggesting an association of breastfeeding with postpartum weight change was lacking.

This review supports the hypothesis that breastfeeding is protective against breast and ovarian carcinoma, and exclusive breastfeeding and predominant breastfeeding increase the duration of lactational amenorrhoea. There is evidence that breastfeeding reduces the risk of type 2 diabetes. However, an association between breastfeeding and bone mineral density or maternal depression or postpartum weight change was not evident.

Keywords: Breastfeeding, Long and Short Term, Maternal health, Meta-analysis

Introduction

Breast milk is the natural first food for newborns. It provides all the energy and nutrients that an infant needs for the first six months of life, up to half or more during the second half of infancy and up to one-third during the second year of life ( 1 , 2 ). For mothers, breastfeeding has been reported to confer lower risk of breast and ovarian carcinoma ( 3 , 4 ), greater postpartum weight loss ( 5 ) and decreased blood pressure ( 6 ) compared with no breastfeeding. The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends exclusive breastfeeding in the first six months and continuation of breastfeeding for 2 years and beyond ( 1 ).

The association between breastfeeding and breast carcinoma in mothers has received increased scrutiny in recent years. A number of studies have suggested that breastfeeding, particularly for an extended period of time, may be associated with a decreased risk of breast carcinoma, even after adjustment for potential confounders ( 7 ). It is difficult, however, to estimate the magnitude of association between breastfeeding duration and breast carcinoma if any, because of the different methodologies used in breastfeeding histories. Parity is also a protective factor against breast carcinoma ( 8 ), and there may be an interaction between parity and breastfeeding duration interplay in protecting women from breast carcinoma.

Longer duration of breastfeeding protects against breast and ovarian carcinoma.

Exclusive breastfeeding and predominant breastfeeding increase the duration of lactational amenorrhoea.

Evidence on the association between breastfeeding and maternal bone mineral density, maternal depression or postpartum weight change was lacking.

Ovarian cancer is one of the most common cancers in female ( 9 , 10 ). Reproductive factors have been identified as markers of risk for ovarian cancer. These reproductive factors mainly include total number of pregnancies, parity, age at menarche and menopause, as well as breastfeeding ( 11 ). Evidence from previous analyses indicates an inverse association between breastfeeding and the risk of ovarian carcinoma ( 4 , 12 ).

Calcium metabolism and bone metabolism are substantially altered with increased calcium demands during pregnancy and lactation. Bone densities can decrease by between 3 and 10 per cent in the span of a few months in a healthy mother ( 13 ). Confounders commonly considered in the studies of the relationship between fracture risk and breastfeeding are age, hormone replacement therapy, parity and BMI ( 4 ).

Available literature suggests that breastfeeding reduces the risk of maternal type 2 diabetes in some cohort studies, but the evidence from published studies has differed with regard to the strength of the association ( 14 , 15 ).

The literature suggests that exclusive breastfeeding protects against pregnancy ( 16 , 17 ). Some studies, however, show that exclusive breastfeeding is not always associated with inhibition of ovulation ( 18 , 19 ).

The incidence of postpartum depression (PPD) is high (10–15%) ( 20 ), and depression during pregnancy usually continues into the postpartum period ( 21 ). Postpartum depression has an immediate impact on mothers. It carries long-term risks for their mental health ( 22 ) and may also have significant negative effects on the cognitive, social and physical development of their children ( 23 ). The evidence for an association between breastfeeding and PPD is, however, unclear ( 23 , 24 ).

Postpartum weight retention is a predictor for future overweight and obesity ( 25 ) and is associated with obesity-related illnesses, such as type 2 diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular disease ( 26 ). Breastfeeding may promote weight loss due to lactation ( 27 ), but there is a lack of strong evidence to support this hypothesis ( 28 ).

We conducted this review to summarise the literature and explore the relationship of breastfeeding and its duration with long-term (breast carcinoma, ovarian carcinoma, osteoporosis and type 2 diabetes mellitus) and short-term (lactational amenorrhoea, postpartum depression, postpartum weight change) maternal health outcomes. Outcomes for review were selected during an expert meeting at the World Health Organization (October 2014) that was reviewing the impact of breastfeeding on maternal and child health.

A search strategy (Box 1 ) was developed and reviewed by all authors. Medical Subject Heading ( 29 ) terms and keywords were used in various combinations. We searched published literature from PubMed, Cochrane Library and CABI databases to identify studies examining the effect of type and duration of breastfeeding on maternal health outcomes. We conducted the search in February 2015. No language or date restrictions were employed in the electronic search.

Box 1. Search strategy for breastfeeding & maternal health

Breastfeeding OR Breast Feeding OR Lactation OR Human Milk OR Breast Milk

Women OR Maternal OR Postpartum OR puerperal OR postnatal OR Birth OR gestation

Diabetes OR (Breast AND (Carcinoma OR carcinoma OR tumor OR malignancy)) OR (Ovarian OR Ovary AND (Carcinoma OR carcinoma OR tumor OR malignancy)) OR (depression OR Blues OR psychosis) OR (Amenorrhea OR Contraception) OR (Osteoporosis OR Bone mineral density) OR Weight OR BMI OR body mass index

(Addresses[ptyp] OR Autobiography[ptyp] OR Bibliography[ptyp] OR Biography[ptyp] OR pubmed books[filter] OR Case Reports[ptyp] OR Congresses[ptyp] OR Consensus Development Conference[ptyp] OR Directory[ptyp] OR Duplicate Publication[ptyp] OR Editorial[ptyp] OR Festschrift[ptyp] OR Guideline[ptyp] OR In Vitro [ptyp] OR Interview[ptyp] OR Lectures[ptyp] OR Legal Cases[ptyp] OR News[ptyp] OR Newspaper Article[ptyp] OR Personal Narratives[ptyp] OR Portraits[ptyp] OR Retracted Publication[ptyp] OR Twin Study[ptyp] OR Video-Audio Media[ptyp])

#1 AND #2 AND #3

Two review authors (RC and BS) screened the titles and abstracts independently to identify potentially relevant citations. These review authors retrieved the full texts of all potentially relevant articles and independently assessed the eligibility of the studies using predefined inclusion criteria. We extracted data from all articles found to be relevant by both authors. Any disagreements or discrepancies between reviewers were resolved by discussion and if necessary by consulting a third author (JSM). In addition to the electronic search, we searched reference lists of the articles identified. We used Web-based citation index for citing manuscripts of these identified articles.

We identified four recent systematic reviews addressing the following outcomes: ovarian carcinoma ( 30 ), type 2 diabetes mellitus ( 31 ), postpartum depression ( 32 ) and postpartum weight change ( 33 ). We planned to update these reviews and provide new quantitative estimates of breastfeeding on these health outcomes. For other maternal health outcomes, that is breast carcinoma, osteoporosis and lactational amenorrhoea, we planned for new reviews.

Inclusion criteria

We selected all observational studies (prospective/retrospective cohort and case–control), randomised controlled trials (RCTs), including cluster randomised trials, and quasi-experimental trials which examined the impact of duration and type of breastfeeding on maternal health outcomes. For articles not written in English, we attempted to get an English abstract. If it was not available, the article was excluded.

Abstraction, summary measure, breastfeeding categories and analysis

We abstracted data using a modified Cochrane data abstraction form. If a study provided separate estimates for hospital- and community-based populations, then the outcome estimates were pooled separately. We used odds ratios (ORs), both adjusted and unadjusted, as our outcome estimate for breast and ovarian carcinoma. Relative risk (RR) was used as the outcome estimate for lactational amenorrhoea. To examine the effect on breast and ovarian carcinoma, breastfeeding was categorised into ever breastfed vs. never breastfed and also by breastfeeding duration, that is breastfed less than six months vs. not breastfed; breastfed 6 to 12 months vs. not breastfed; and breastfed >12 months vs. not breastfed. For lactational amenorrhoea, we used exclusive, predominant, partial, any and no breastfeeding as the categories (Table A1 ). Standardised mean differences in bone mineral density between highest and lowest breastfeeding duration categories were used for osteoporosis outcome. A narrative approach was used to summarise the studies for postpartum weight change as the studies were very heterogeneous.

We performed meta-analysis with Stata 11.2 software (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA). We calculated the pooled estimates of the outcome measures from the odds ratios (ORs), relative risks (RRs), standardised mean differences (SMDs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of the individual studies by inverse variance or DerSimonian and Laird method in Stata ( 34 ). High heterogeneity was defined by either a low p-value (<0.10) or I 2 value greater than 60%. In cases of high heterogeneity, the random-effects model was used and causes were explored by conducting subgroup analysis and meta-regression. Subgroup analyses were carried out based on breastfeeding categories (ever vs never, less than six months vs never, 6–12 months vs never, >12 months vs never). Among the ever vs never breastfeeding category, subgroup analyses were carried out based on sample size (<500, 500–1499, ≥1500), individual study setting (i.e. high-income country (HIC) or low- and middle-income country (LMIC) ( 35 )), study design (cohort, case–control), mean age of diagnosis (≤49 years, >49 years), adjustment for parity (fine adjustment, i.e. adjustment according to each parity number measured as 0, 1, 2, 3, 4+; crude adjustment, i.e. groupwise adjustment measured as 0, 1–3, 4+ children; and no adjustment), control for confounding (thorough, i.e. controlled for all potential socio-demographic and reproductive factors such as age, income, ethnicity, parity, contraceptive use, family history of carcinoma, menopausal status and smoking; partial, i.e. only partially controlled for potential socio-demographic and reproductive factors; and none) and quality of study (adequate, i.e. study had none or one among selection bias, measurement bias, attrition (20%) and confounding bias; inadequate) ( 36 ). We also evaluated the presence of publication bias in the extracted data for the primary outcome using Begg's test or Egger's test or funnel plots ( 37 ).

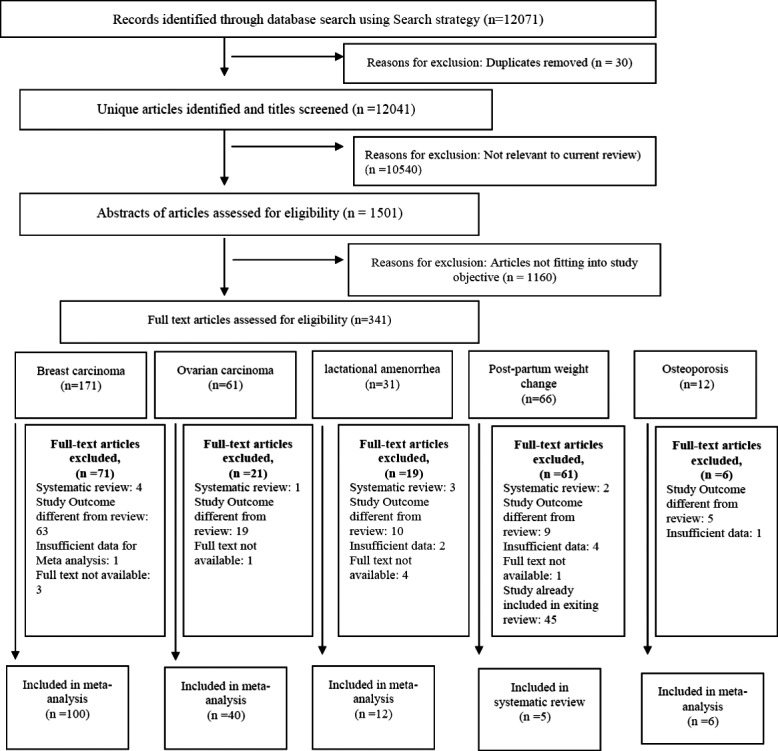

We screened the 12 071 titles identified. Of these, after reviewing abstracts of 1501 articles, we selected 341 for full-text review. We identified 163 articles for inclusion in our final database (Fig. 1 ). Among these, 100 studies examined the impact of breastfeeding on breast carcinoma, 40 studies on ovarian carcinoma, 12 studies on lactational amenorrhoea, five studies on postpartum weight change and six studies on osteoporosis. We did fresh meta-analysis for breast carcinoma, ovarian carcinoma, osteoporosis and lactational amenorrhoea and updated the review on postpartum weight change. No new studies subsequent to the existing reviews on type 2 diabetes mellitus and postpartum depression ( 31 , 32 ) were found to be eligible for inclusion.

: Prisma Flow chart.

Effects of breastfeeding on long-term maternal health outcomes

Breast carcinoma.

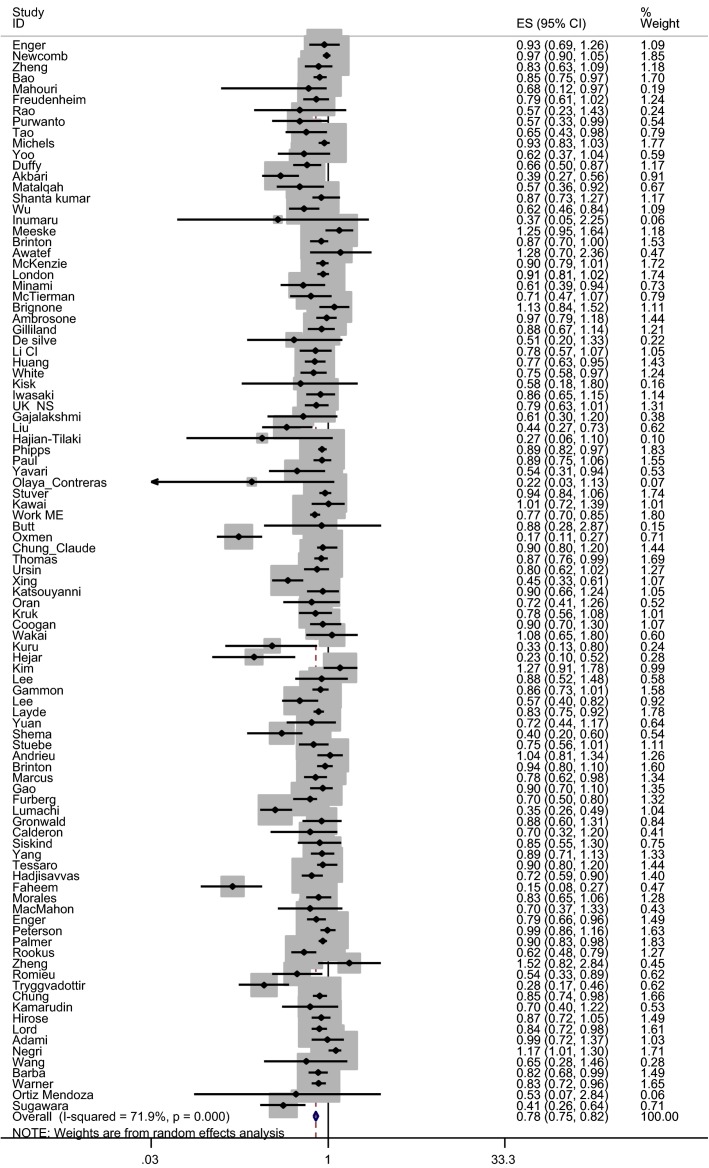

We identified 98 estimates ( 38 – 135 ) of the association between ever breastfeeding and breast carcinoma risk (Tables 1 and A2 ). Ever breastfeeding was associated with 22% (OR 0.78, 95% CI 0.74–0.82) (Fig. 2 ) reduction of breast carcinoma risk compared with never breastfeeding. Compared with no breastfeeding, breastfeeding for less than six months (39 estimates) and breastfeeding for 6–12 months (36 estimates) were associated with 7% (OR 0.93, 95% CI 0.88–0.99) and 9% (OR 0.91, 95% CI 0.87–0.96) risk reduction of breast carcinoma, respectively. We found that mothers who breastfed for >12 months compared with those who did not breastfeed had a 26% lower risk of developing breast carcinoma (50 studies; OR 0.74, 95% CI 0.69–0.79), and when restricted to high-quality studies, only (41 studies) breastfeeding >12 months was associated with 23% lower risk of developing breast carcinoma (OR 0.77, 95% CI 0.72–0.83) (not shown in Table 1 ). There was, however, an indication of publication bias. Asymmetry was observed in funnel plot when inspected visually. Both Egger's test (p bias <0.001) and Begg's test (p bias <0.001) showed statistically significant findings.

Risk of breast carcinoma by breastfeeding duration and by subgroup

Effect of ever breastfeeding vs. no breastfeeding on risk of breast carcinoma.

Subgroup analysis of the effects of ever breastfeeding on risk of breast carcinoma among studies conducted in high-income countries, with large sample sizes (>1500), of cohort design, with thorough control of confounding factors and adequate quality showed a smaller breast carcinoma risk reduction. Studies where fine adjustment for parity was made showed a smaller effect of breastfeeding on breast carcinoma risk reduction (OR 0.92, 95% CI 0.88–0.96) compared with studies where crude adjustment or no adjustment was made. A restricted analysis including parous women in the fine adjustment subgroup showed a risk reduction of 7% for breast carcinoma (OR 0.93, 95% CI 0.89–0.97; 14 estimates) (not shown in Table 1 ).

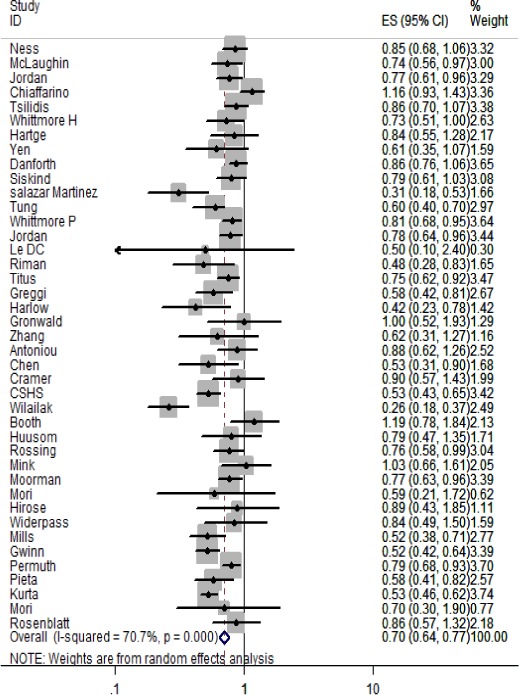

Ovarian carcinoma

Pooled results from 41 estimates ( 65 , 69 , 136 – 173 ) showed that mothers who ever breastfed their children had a 30% reduction in the risk of ovarian carcinoma, when compared with those who never breastfed (OR 0.70, 95% CI 0.64–0.77) (Tables 2 and A3 ; Fig. 3 ). The risk of ovarian carcinoma was 17% lower among women who had breastfed for less than six months when compared with those who did not breastfeed (OR 0.83, 95% CI 0.78–0.89). The risk of ovarian carcinoma among mothers who breastfed for 6–12 months was 28% lower (OR 0.72, 95% CI 0.66–0.78; 19 estimates) when compared with women who had not breastfed. The highest risk reduction was observed among women who breastfed for more than 12 months, in whom the risk of ovarian carcinoma was 37% lower than among women who had not breastfed (OR 0.63; 95% CI 0.56–0.71; 29 estimates). The effect size was slightly less (OR 0.65, 95% CI 0.57–0.73), when the analyses were restricted to high-quality studies (29 estimates). There was no evidence of publication bias in Egger's test or Begg's test (p bias >0.1) in either of the analyses.

Risk of ovarian carcinoma by breastfeeding duration and by subgroup

Effect on ever vs. never breastfeeding on risk of ovarian carcinoma.

In subgroup analysis, studies with sample sizes of more than 1500 showed a significant protection of 24% from ovarian carcinoma (OR 0.76, 95% CI 0.69–0.84). This effect size was reduced compared to studies with smaller samples (OR 0.67, 95% CI 0.53–0.84). Studies in HICs also showed a significant but reduced effect (OR 0.74, 95% CI 0.68–0.80) compared with studies in LMICs (OR 0.48 95% CI 0.29–0.77). Lower quality studies showed a higher risk reduction for ovarian carcinoma (OR 0.63, 95% CI 0.58–0.68) than higher quality studies (OR 0.72, 95% CI 0.65–0.80). Studies where fine adjustment for parity was made showed a modest but still significant (OR 0.80, 95% CI 0.75–0.86) reduction in risk of ovarian carcinoma compared with studies where no or crude adjustment for parity was made. In an analysis restricted to parous women in the fine adjustment subgroup, the effect was further attenuated (OR 0.82, 95% CI 0.75–0.89) (not shown in Table 2 ).

Osteoporosis

A total of six studies ( 174 – 179 ) were identified (Table 3 ). Two studies were from LMICs ( 174 , 178 ) and four studies from HICs ( 175 – 177 , 179 ). Bone mineral density (BMD) was generally measured at two sites, that is femoral neck and distal radius. For femoral neck, four studies ( 175 , 177 – 179 ) were identified with small sample size (total 489 women). The pooled effect suggests that breastfeeding had a nonsignificant effect on femoral neck bone mass. With respect to distal radius, four studies ( 174 – 177 ) were identified and the results were heterogeneous. The largest (n = 963) study ( 176 ) did not observe any association, whereas Chowdhury et al. ( 174 ) (n = 400) reported a negative effect of breastfeeding on bone mineral density. Overall, there was no clear evidence of an effect of breastfeeding on osteoporosis.

Association between breastfeeding and bone mineral density

BMD, bone mineral density; SD, standard deviation; SMD, standardised mean difference.

A recent systematic review by Aune reported a reduced risk of type 2 diabetes (RR 0.68 95% CI: 0.57–0.82) with longer duration of lifetime breastfeeding compared with shorter durations. A one-year increase in the total lifetime duration of breastfeeding was associated with 9% protection (RR 0.91, 95% CI: 0.86–0.96) against the presence of type 2 diabetes in the mothers. No new studies were found subsequent to the systemic review by Aune et al. in 2013.

Effects of breastfeeding on short-term maternal health outcomes

Lactational amenorrhoea.

We identified 12 studies ( 173 , 180 – 190 ) that examined the association between breastfeeding and lactational amenorrhoea (Table 4 ). Four studies ( 180 , 182 , 188 , 185 ) did not provide either RR or OR. They reported that exclusive compared to mixed feeding, or longer duration of any breastfeeding, was associated with an increased mean or median duration of lactational amenorrhoea. The remaining studies provided data from which the following estimates were derived: the probability of continued lactational amenorrhoea at six months postpartum was 23% higher (RR 1.23, 95% CI 1.07–1.41; three studies) for exclusive or predominant breastfeeding compared to no breastfeeding, and 21% higher (RR 1.21, 95% CI 1.01–1.25; five studies) (Table 4 ) when compared to partial breastfeeding. We found no evidence of publication bias.

Effect of breastfeeding on probability of lactational amenorrhoea

Postpartum depression

A recent systematic review conducted by Dias et al. reported that pregnancy depression predicts a shorter breastfeeding duration, but evidence is unclear on whether breastfeeding mediates the association between pregnancy and postpartum depression. No new studies were found subsequent to the systemic review conducted by Dias and Figueiredo in ( 32 ).

Postpartum weight change

We updated the systematic review by Neville et al. ( 33 ) by including 5 additional studies (Table 5 ) ( 191 – 195 ). In the review by Neville et al., the majority of identified studies reported little or no association between breastfeeding and weight change. Of those five studies, three studies were performed in low- and middle-income countries, one was performed in high-income country, and one was multicentre study (Brazil, Ghana, India, Norway, Oman, USA). In studies performed in low- and middle-income countries, we have not found any potential differential effect for breastfeeding and postpartum weight loss response as a function of countries being low to middle and high income. Two of the five additionally identified studies ( 194 , 195 ) reported a significant reduction in postpartum weight with breastfeeding. Sarkar and Taylor ( 191 ) in a cross-sectional study in Bangladesh revealed that body weight of mothers was negatively correlated with 1–12 and 13–24 months of lactation after controlling for height, education and food consumption. Stuebe et al. ( 192 ) showed that women who exclusively breastfed for greater than six months had the lowest BMI at 3 years postpartum as well as the lowest postpartum weight retention at 3 years compared with women who never exclusively breastfed. A multicentre study showed that lactation intensity and duration explained little variation in weight change patterns ( 193 – 195 ). Overall, the role of breastfeeding on postpartum weight change remains unclear.

Overview of studies which examined the association between breastfeeding and postpartum weight change

The aim of this review was to systematically examine the effect of breastfeeding on important maternal health outcomes.

The risk of developing breast carcinoma was reduced by 26% among women who cumulatively breastfed for more than 12 months, compared with women who did not breast feed.

Previous reviews suggested that breastfeeding was not strongly related to risk of breast carcinoma ( 196 , 197 ) or found a small but statistically significant protective association ( 198 – 200 ). Our meta-analysis findings are comparable with but suggest a higher level of protection than that found by the Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast Carcinoma ( 201 ). In this pooled analysis of approximately 50 000 carcinoma cases from 47 studies in 30 countries around the world and after adjustment for confounders including parity and exclusion of nulliparous women, the authors estimated that the risk of invasive breast carcinoma decreased by 4.3% for every 12 months of breastfeeding ( 201 ). However, one of the challenges of comparing studies on cumulative breastfeeding duration and determining the effect on breast carcinoma risk is the lack of a standard protocol for grouping the lifetime number of months of breastfeeding for analysis and the adjustment of parity. Lifetime duration of breastfeeding is related to the number of children breastfed, that is parity and the duration of breastfeeding for each child. Our results showed that when controlled for parity, breastfeeding independently contributed to a modest but significant risk reduction for breast carcinoma. The risk reduction for breast carcinoma was 8% among ever breastfed mothers when finely adjusted for parity, while it was 22% when all studies were pooled together. Even when our analysis was restricted to only parous women, finely adjusted for parity, ever breastfeeding was associated with a 7% reduction in risk of breast carcinoma compared with never breastfeeding. Longer duration of breastfeeding (>12 months) was associated with more protection of breast carcinoma than shorter duration of breastfeeding (breastfeeding <6 and 6–12 months) when compared to never breastfeeding. Even when our analysis was restricted to studies with adequate quality, breastfeeding >12 months showed more protection against breast carcinoma. Possible biological mechanisms include that protection may occur through parity-specific changes in levels of circulating hormones such as estradiol, prolactin and growth hormone, as each of these has been associated with breast cancer risk ( 202 ), or that the parous mammary gland may contain epithelial cells with a more differentiated and less proliferative character which are less susceptible to transformation ( 203 ).

Breastfeeding by women for more than 12 months was also associated with a 35% reduction in ovarian cancer, compared with women who had not breastfed. The protective effect was less in women who had only ever breastfed (for any duration) ranging from 30% in an unadjusted analysis to 18% when the analysis was restricted to ever breastfeeding parous women (finely adjusted for parity). A number of physiological mechanisms may account for the protective effect of breastfeeding against ovarian cancer through modulating ovarian cycle length ( 204 ), and therefore, parity is an important confounder. Longer duration of breastfeeding suppresses ovulation longer and causes suppression of gonadotropins, resulting in depressed production of plasma estradiol, considered to be a potential causal mechanism of ovarian cancer when present at high levels ( 205 ). However, breastfeeding must also have an independent effect to explain the estimated reduction in ovarian cancer when parity is adjusted for.

There did not appear to be a significant effect of breastfeeding on the risk of osteoporosis. Calcium metabolism and bone metabolism are substantially altered during pregnancy and lactation, and high calcium demand during lactation makes women more prone to bone resorption and subsequent osteoporosis. There was no evidence of such risk, and it has been suggested that during lactation, oestrogen imposes minor inhibitory effect on periosteal bone formation and permits periosteal expansion which increases bone size after weaning ( 206 ).

Available review suggests that longer duration of breastfeeding reduces risk of development of type 2 diabetes mellitus by 32%, and in linear dose–response analyses, there was a 9% reduction in relative risk for each 12-month increase in lifetime duration of breastfeeding. Our review shows that exclusive or predominant breastfeeding during the first six months postpartum was associated with longer periods of amenorrhoea. Less intensive breastfeeding, captured under ‘any or partial breastfeeding’, offers less clear benefit. This finding is biologically plausible. Breastfeeding suppresses the resumption of ovarian activity after childbirth and is thus associated with a period of infertility. Exclusive breastfeeding and predominant breastfeeding are associated with a higher frequency of suckling than other patterns of breastfeeding. Frequent suckling inhibits gonadotropin-releasing hormone and decreases the release of luteinising hormone and follicle-stimulating hormone ( 207 ), thus preventing early return of menses.

The association between breastfeeding and postpartum weight change remains uncertain. Factors such as age, gestational weight gain and prepregnancy weight confound such analyses ( 208 , 209 ). As prepregnancy weight and gestational weight gain were found to be strong determinant factors of postpartum weight change, future research should include the preconception period with continued monitoring into the postpartum period to capture the true trajectory of weight change. Even though BF may not lead to postpartum weight loss under ‘natural’ conditions, it remains unknown whether women who wish to lose weight intentionally in the postpartum period are more likely to be successful at doing so if they are vs. if they are not breastfeeding.

Although our original review plans included exploring the associations between breastfeeding and the risk of maternal postpartum depression and type 2 diabetes, we were unable to identify new studies following the reviews published in 2015 ( 31 ) and 2013 ( 32 ). The evidence suggests that the relationship between breastfeeding and postpartum depression is lacking.

The range of the maternal outcomes examined and the various categories of breastfeeding exposures that we considered are important strengths of this review. Despite the expanded scope of review, other important maternal health outcomes such as maternal hypertension and cardiovascular disease were not addressed and should be considered in future research and reviews. Also important was the attempt to look for dose–response relationships and the evaluation of heterogeneity and publication biases. However, some limitations should be acknowledged. We have pooled data from many observational studies that are prone to be affected by biases such as in recall or due to selection. Some studies did not control for or collect information on potential confounders that could have affected the association between breastfeeding and the outcome of interest. For postpartum weight change, we were constrained to take a narrative approach to present the outcomes because of the heterogeneous nature of the studies. In cases of significant heterogeneity in study results, we have performed post hoc subgroup analysis and meta-regression and have used the random-effects model. But in some cases even within subgroups, there was significant heterogeneity which suggests some other unidentified factors causing such heterogeneity. Although the meta-regression seemed to explain around 80% of the heterogeneity for breast and ovarian carcinoma, we need to acknowledge the limitation of post hoc subgroup analysis.

Our meta-analysis shows that women who had ever breastfed and who breastfed for longer duration have a lower risk of breast and ovarian carcinoma and also type 2 diabetes mellitus. Exclusive or predominant breastfeeding during the first six months postpartum prolongs lactational amenorrhoea. We found no evidence of a clear association between breastfeeding and bone mineral density, maternal depression or postpartum weight change.

Acknowledgments