Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

- Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

Writing Survey Questions

Perhaps the most important part of the survey process is the creation of questions that accurately measure the opinions, experiences and behaviors of the public. Accurate random sampling will be wasted if the information gathered is built on a shaky foundation of ambiguous or biased questions. Creating good measures involves both writing good questions and organizing them to form the questionnaire.

Questionnaire design is a multistage process that requires attention to many details at once. Designing the questionnaire is complicated because surveys can ask about topics in varying degrees of detail, questions can be asked in different ways, and questions asked earlier in a survey may influence how people respond to later questions. Researchers are also often interested in measuring change over time and therefore must be attentive to how opinions or behaviors have been measured in prior surveys.

Surveyors may conduct pilot tests or focus groups in the early stages of questionnaire development in order to better understand how people think about an issue or comprehend a question. Pretesting a survey is an essential step in the questionnaire design process to evaluate how people respond to the overall questionnaire and specific questions, especially when questions are being introduced for the first time.

For many years, surveyors approached questionnaire design as an art, but substantial research over the past forty years has demonstrated that there is a lot of science involved in crafting a good survey questionnaire. Here, we discuss the pitfalls and best practices of designing questionnaires.

Question development

There are several steps involved in developing a survey questionnaire. The first is identifying what topics will be covered in the survey. For Pew Research Center surveys, this involves thinking about what is happening in our nation and the world and what will be relevant to the public, policymakers and the media. We also track opinion on a variety of issues over time so we often ensure that we update these trends on a regular basis to better understand whether people’s opinions are changing.

At Pew Research Center, questionnaire development is a collaborative and iterative process where staff meet to discuss drafts of the questionnaire several times over the course of its development. We frequently test new survey questions ahead of time through qualitative research methods such as focus groups , cognitive interviews, pretesting (often using an online, opt-in sample ), or a combination of these approaches. Researchers use insights from this testing to refine questions before they are asked in a production survey, such as on the ATP.

Measuring change over time

Many surveyors want to track changes over time in people’s attitudes, opinions and behaviors. To measure change, questions are asked at two or more points in time. A cross-sectional design surveys different people in the same population at multiple points in time. A panel, such as the ATP, surveys the same people over time. However, it is common for the set of people in survey panels to change over time as new panelists are added and some prior panelists drop out. Many of the questions in Pew Research Center surveys have been asked in prior polls. Asking the same questions at different points in time allows us to report on changes in the overall views of the general public (or a subset of the public, such as registered voters, men or Black Americans), or what we call “trending the data”.

When measuring change over time, it is important to use the same question wording and to be sensitive to where the question is asked in the questionnaire to maintain a similar context as when the question was asked previously (see question wording and question order for further information). All of our survey reports include a topline questionnaire that provides the exact question wording and sequencing, along with results from the current survey and previous surveys in which we asked the question.

The Center’s transition from conducting U.S. surveys by live telephone interviewing to an online panel (around 2014 to 2020) complicated some opinion trends, but not others. Opinion trends that ask about sensitive topics (e.g., personal finances or attending religious services ) or that elicited volunteered answers (e.g., “neither” or “don’t know”) over the phone tended to show larger differences than other trends when shifting from phone polls to the online ATP. The Center adopted several strategies for coping with changes to data trends that may be related to this change in methodology. If there is evidence suggesting that a change in a trend stems from switching from phone to online measurement, Center reports flag that possibility for readers to try to head off confusion or erroneous conclusions.

Open- and closed-ended questions

One of the most significant decisions that can affect how people answer questions is whether the question is posed as an open-ended question, where respondents provide a response in their own words, or a closed-ended question, where they are asked to choose from a list of answer choices.

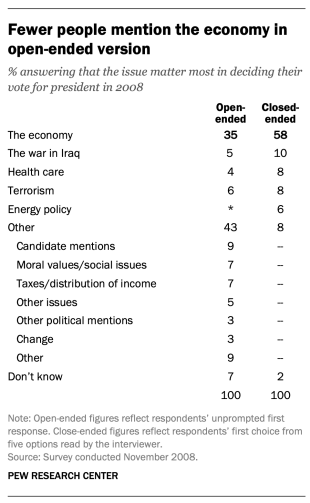

For example, in a poll conducted after the 2008 presidential election, people responded very differently to two versions of the question: “What one issue mattered most to you in deciding how you voted for president?” One was closed-ended and the other open-ended. In the closed-ended version, respondents were provided five options and could volunteer an option not on the list.

When explicitly offered the economy as a response, more than half of respondents (58%) chose this answer; only 35% of those who responded to the open-ended version volunteered the economy. Moreover, among those asked the closed-ended version, fewer than one-in-ten (8%) provided a response other than the five they were read. By contrast, fully 43% of those asked the open-ended version provided a response not listed in the closed-ended version of the question. All of the other issues were chosen at least slightly more often when explicitly offered in the closed-ended version than in the open-ended version. (Also see “High Marks for the Campaign, a High Bar for Obama” for more information.)

Researchers will sometimes conduct a pilot study using open-ended questions to discover which answers are most common. They will then develop closed-ended questions based off that pilot study that include the most common responses as answer choices. In this way, the questions may better reflect what the public is thinking, how they view a particular issue, or bring certain issues to light that the researchers may not have been aware of.

When asking closed-ended questions, the choice of options provided, how each option is described, the number of response options offered, and the order in which options are read can all influence how people respond. One example of the impact of how categories are defined can be found in a Pew Research Center poll conducted in January 2002. When half of the sample was asked whether it was “more important for President Bush to focus on domestic policy or foreign policy,” 52% chose domestic policy while only 34% said foreign policy. When the category “foreign policy” was narrowed to a specific aspect – “the war on terrorism” – far more people chose it; only 33% chose domestic policy while 52% chose the war on terrorism.

In most circumstances, the number of answer choices should be kept to a relatively small number – just four or perhaps five at most – especially in telephone surveys. Psychological research indicates that people have a hard time keeping more than this number of choices in mind at one time. When the question is asking about an objective fact and/or demographics, such as the religious affiliation of the respondent, more categories can be used. In fact, they are encouraged to ensure inclusivity. For example, Pew Research Center’s standard religion questions include more than 12 different categories, beginning with the most common affiliations (Protestant and Catholic). Most respondents have no trouble with this question because they can expect to see their religious group within that list in a self-administered survey.

In addition to the number and choice of response options offered, the order of answer categories can influence how people respond to closed-ended questions. Research suggests that in telephone surveys respondents more frequently choose items heard later in a list (a “recency effect”), and in self-administered surveys, they tend to choose items at the top of the list (a “primacy” effect).

Because of concerns about the effects of category order on responses to closed-ended questions, many sets of response options in Pew Research Center’s surveys are programmed to be randomized to ensure that the options are not asked in the same order for each respondent. Rotating or randomizing means that questions or items in a list are not asked in the same order to each respondent. Answers to questions are sometimes affected by questions that precede them. By presenting questions in a different order to each respondent, we ensure that each question gets asked in the same context as every other question the same number of times (e.g., first, last or any position in between). This does not eliminate the potential impact of previous questions on the current question, but it does ensure that this bias is spread randomly across all of the questions or items in the list. For instance, in the example discussed above about what issue mattered most in people’s vote, the order of the five issues in the closed-ended version of the question was randomized so that no one issue appeared early or late in the list for all respondents. Randomization of response items does not eliminate order effects, but it does ensure that this type of bias is spread randomly.

Questions with ordinal response categories – those with an underlying order (e.g., excellent, good, only fair, poor OR very favorable, mostly favorable, mostly unfavorable, very unfavorable) – are generally not randomized because the order of the categories conveys important information to help respondents answer the question. Generally, these types of scales should be presented in order so respondents can easily place their responses along the continuum, but the order can be reversed for some respondents. For example, in one of Pew Research Center’s questions about abortion, half of the sample is asked whether abortion should be “legal in all cases, legal in most cases, illegal in most cases, illegal in all cases,” while the other half of the sample is asked the same question with the response categories read in reverse order, starting with “illegal in all cases.” Again, reversing the order does not eliminate the recency effect but distributes it randomly across the population.

Question wording

The choice of words and phrases in a question is critical in expressing the meaning and intent of the question to the respondent and ensuring that all respondents interpret the question the same way. Even small wording differences can substantially affect the answers people provide.

[View more Methods 101 Videos ]

An example of a wording difference that had a significant impact on responses comes from a January 2003 Pew Research Center survey. When people were asked whether they would “favor or oppose taking military action in Iraq to end Saddam Hussein’s rule,” 68% said they favored military action while 25% said they opposed military action. However, when asked whether they would “favor or oppose taking military action in Iraq to end Saddam Hussein’s rule even if it meant that U.S. forces might suffer thousands of casualties, ” responses were dramatically different; only 43% said they favored military action, while 48% said they opposed it. The introduction of U.S. casualties altered the context of the question and influenced whether people favored or opposed military action in Iraq.

There has been a substantial amount of research to gauge the impact of different ways of asking questions and how to minimize differences in the way respondents interpret what is being asked. The issues related to question wording are more numerous than can be treated adequately in this short space, but below are a few of the important things to consider:

First, it is important to ask questions that are clear and specific and that each respondent will be able to answer. If a question is open-ended, it should be evident to respondents that they can answer in their own words and what type of response they should provide (an issue or problem, a month, number of days, etc.). Closed-ended questions should include all reasonable responses (i.e., the list of options is exhaustive) and the response categories should not overlap (i.e., response options should be mutually exclusive). Further, it is important to discern when it is best to use forced-choice close-ended questions (often denoted with a radio button in online surveys) versus “select-all-that-apply” lists (or check-all boxes). A 2019 Center study found that forced-choice questions tend to yield more accurate responses, especially for sensitive questions. Based on that research, the Center generally avoids using select-all-that-apply questions.

It is also important to ask only one question at a time. Questions that ask respondents to evaluate more than one concept (known as double-barreled questions) – such as “How much confidence do you have in President Obama to handle domestic and foreign policy?” – are difficult for respondents to answer and often lead to responses that are difficult to interpret. In this example, it would be more effective to ask two separate questions, one about domestic policy and another about foreign policy.

In general, questions that use simple and concrete language are more easily understood by respondents. It is especially important to consider the education level of the survey population when thinking about how easy it will be for respondents to interpret and answer a question. Double negatives (e.g., do you favor or oppose not allowing gays and lesbians to legally marry) or unfamiliar abbreviations or jargon (e.g., ANWR instead of Arctic National Wildlife Refuge) can result in respondent confusion and should be avoided.

Similarly, it is important to consider whether certain words may be viewed as biased or potentially offensive to some respondents, as well as the emotional reaction that some words may provoke. For example, in a 2005 Pew Research Center survey, 51% of respondents said they favored “making it legal for doctors to give terminally ill patients the means to end their lives,” but only 44% said they favored “making it legal for doctors to assist terminally ill patients in committing suicide.” Although both versions of the question are asking about the same thing, the reaction of respondents was different. In another example, respondents have reacted differently to questions using the word “welfare” as opposed to the more generic “assistance to the poor.” Several experiments have shown that there is much greater public support for expanding “assistance to the poor” than for expanding “welfare.”

We often write two versions of a question and ask half of the survey sample one version of the question and the other half the second version. Thus, we say we have two forms of the questionnaire. Respondents are assigned randomly to receive either form, so we can assume that the two groups of respondents are essentially identical. On questions where two versions are used, significant differences in the answers between the two forms tell us that the difference is a result of the way we worded the two versions.

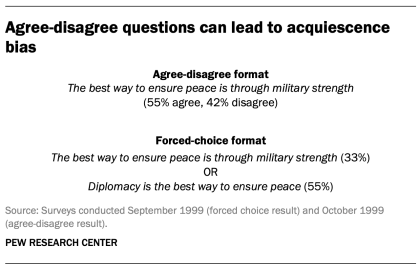

One of the most common formats used in survey questions is the “agree-disagree” format. In this type of question, respondents are asked whether they agree or disagree with a particular statement. Research has shown that, compared with the better educated and better informed, less educated and less informed respondents have a greater tendency to agree with such statements. This is sometimes called an “acquiescence bias” (since some kinds of respondents are more likely to acquiesce to the assertion than are others). This behavior is even more pronounced when there’s an interviewer present, rather than when the survey is self-administered. A better practice is to offer respondents a choice between alternative statements. A Pew Research Center experiment with one of its routinely asked values questions illustrates the difference that question format can make. Not only does the forced choice format yield a very different result overall from the agree-disagree format, but the pattern of answers between respondents with more or less formal education also tends to be very different.

One other challenge in developing questionnaires is what is called “social desirability bias.” People have a natural tendency to want to be accepted and liked, and this may lead people to provide inaccurate answers to questions that deal with sensitive subjects. Research has shown that respondents understate alcohol and drug use, tax evasion and racial bias. They also may overstate church attendance, charitable contributions and the likelihood that they will vote in an election. Researchers attempt to account for this potential bias in crafting questions about these topics. For instance, when Pew Research Center surveys ask about past voting behavior, it is important to note that circumstances may have prevented the respondent from voting: “In the 2012 presidential election between Barack Obama and Mitt Romney, did things come up that kept you from voting, or did you happen to vote?” The choice of response options can also make it easier for people to be honest. For example, a question about church attendance might include three of six response options that indicate infrequent attendance. Research has also shown that social desirability bias can be greater when an interviewer is present (e.g., telephone and face-to-face surveys) than when respondents complete the survey themselves (e.g., paper and web surveys).

Lastly, because slight modifications in question wording can affect responses, identical question wording should be used when the intention is to compare results to those from earlier surveys. Similarly, because question wording and responses can vary based on the mode used to survey respondents, researchers should carefully evaluate the likely effects on trend measurements if a different survey mode will be used to assess change in opinion over time.

Question order

Once the survey questions are developed, particular attention should be paid to how they are ordered in the questionnaire. Surveyors must be attentive to how questions early in a questionnaire may have unintended effects on how respondents answer subsequent questions. Researchers have demonstrated that the order in which questions are asked can influence how people respond; earlier questions can unintentionally provide context for the questions that follow (these effects are called “order effects”).

One kind of order effect can be seen in responses to open-ended questions. Pew Research Center surveys generally ask open-ended questions about national problems, opinions about leaders and similar topics near the beginning of the questionnaire. If closed-ended questions that relate to the topic are placed before the open-ended question, respondents are much more likely to mention concepts or considerations raised in those earlier questions when responding to the open-ended question.

For closed-ended opinion questions, there are two main types of order effects: contrast effects ( where the order results in greater differences in responses), and assimilation effects (where responses are more similar as a result of their order).

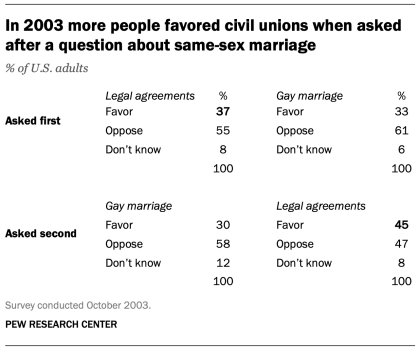

An example of a contrast effect can be seen in a Pew Research Center poll conducted in October 2003, a dozen years before same-sex marriage was legalized in the U.S. That poll found that people were more likely to favor allowing gays and lesbians to enter into legal agreements that give them the same rights as married couples when this question was asked after one about whether they favored or opposed allowing gays and lesbians to marry (45% favored legal agreements when asked after the marriage question, but 37% favored legal agreements without the immediate preceding context of a question about same-sex marriage). Responses to the question about same-sex marriage, meanwhile, were not significantly affected by its placement before or after the legal agreements question.

Another experiment embedded in a December 2008 Pew Research Center poll also resulted in a contrast effect. When people were asked “All in all, are you satisfied or dissatisfied with the way things are going in this country today?” immediately after having been asked “Do you approve or disapprove of the way George W. Bush is handling his job as president?”; 88% said they were dissatisfied, compared with only 78% without the context of the prior question.

Responses to presidential approval remained relatively unchanged whether national satisfaction was asked before or after it. A similar finding occurred in December 2004 when both satisfaction and presidential approval were much higher (57% were dissatisfied when Bush approval was asked first vs. 51% when general satisfaction was asked first).

Several studies also have shown that asking a more specific question before a more general question (e.g., asking about happiness with one’s marriage before asking about one’s overall happiness) can result in a contrast effect. Although some exceptions have been found, people tend to avoid redundancy by excluding the more specific question from the general rating.

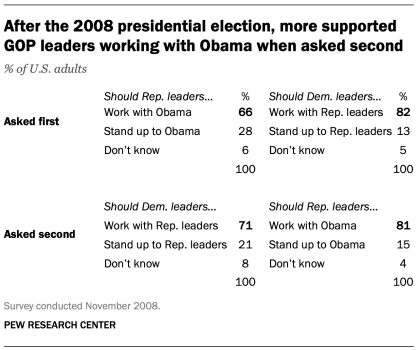

Assimilation effects occur when responses to two questions are more consistent or closer together because of their placement in the questionnaire. We found an example of an assimilation effect in a Pew Research Center poll conducted in November 2008 when we asked whether Republican leaders should work with Obama or stand up to him on important issues and whether Democratic leaders should work with Republican leaders or stand up to them on important issues. People were more likely to say that Republican leaders should work with Obama when the question was preceded by the one asking what Democratic leaders should do in working with Republican leaders (81% vs. 66%). However, when people were first asked about Republican leaders working with Obama, fewer said that Democratic leaders should work with Republican leaders (71% vs. 82%).

The order questions are asked is of particular importance when tracking trends over time. As a result, care should be taken to ensure that the context is similar each time a question is asked. Modifying the context of the question could call into question any observed changes over time (see measuring change over time for more information).

A questionnaire, like a conversation, should be grouped by topic and unfold in a logical order. It is often helpful to begin the survey with simple questions that respondents will find interesting and engaging. Throughout the survey, an effort should be made to keep the survey interesting and not overburden respondents with several difficult questions right after one another. Demographic questions such as income, education or age should not be asked near the beginning of a survey unless they are needed to determine eligibility for the survey or for routing respondents through particular sections of the questionnaire. Even then, it is best to precede such items with more interesting and engaging questions. One virtue of survey panels like the ATP is that demographic questions usually only need to be asked once a year, not in each survey.

U.S. Surveys

Other research methods.

901 E St. NW, Suite 300 Washington, DC 20004 USA (+1) 202-419-4300 | Main (+1) 202-857-8562 | Fax (+1) 202-419-4372 | Media Inquiries

Research Topics

- Email Newsletters

ABOUT PEW RESEARCH CENTER Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan, nonadvocacy fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It does not take policy positions. The Center conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, computational social science research and other data-driven research. Pew Research Center is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts , its primary funder.

© 2024 Pew Research Center

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

13.1 Writing effective survey questions and questionnaires

Learning objectives.

Learners will be able to…

- Describe some of the ways that survey questions might confuse respondents and how to word questions and responses clearly

- Create mutually exclusive, exhaustive, and balanced response options

- Define fence-sitting and floating

- Describe the considerations involved in constructing a well-designed questionnaire

- Discuss why pilot testing is important

In the previous chapter, we reviewed how researchers collect data using surveys. Guided by their sampling approach and research context, researchers should choose the survey approach that provides the most favorable tradeoffs in strengths and challenges. With this information in hand, researchers need to write their questionnaire and revise it before beginning data collection. Each method of delivery requires a questionnaire, but they vary a bit based on how they will be used by the researcher. Since phone surveys are read aloud, researchers will pay more attention to how the questionnaire sounds than how it looks. Online surveys can use advanced tools to require the completion of certain questions, present interactive questions and answers, and otherwise afford greater flexibility in how questionnaires are designed. As you read this chapter, consider how your method of delivery impacts the type of questionnaire you will design.

Start with operationalization

The first thing you need to do to write effective survey questions is identify what exactly you wish to know. As silly as it sounds to state what seems so completely obvious, we can’t stress enough how easy it is to forget to include important questions when designing a survey. Begin by looking at your research question and refreshing your memory of the operational definitions you developed for those variables from Chapter 11. You should have a pretty firm grasp of your operational definitions before starting the process of questionnaire design. You may have taken those operational definitions from other researchers’ methods, found established scales and indices for your measures, or created your own questions and answer options.

TRACK 1 (IF YOU ARE CREATING A RESEARCH PROPOSAL FOR THIS CLASS)

STOP! Make sure you have a complete operational definition for the dependent and independent variables in your research question. A complete operational definition contains the variable being measured, the measure used, and how the researcher interprets the measure. Let’s make sure you have what you need from Chapter 11 to begin writing your questionnaire.

List all of the dependent and independent variables in your research question.

- It’s normal to have one dependent or independent variable. It’s also normal to have more than one of either.

- Make sure that your research question (and this list) contain all of the variables in your hypothesis. Your hypothesis should only include variables from you research question.

For each variable in your list:

- If you don’t have questions and answers finalized yet, write a first draft and revise it based on what you read in this section.

- If you are using a measure from another researcher, you should be able to write out all of the questions and answers associated with that measure. If you only have the name of a scale or a few questions, you need to access to the full text and some documentation on how to administer and interpret it before you can finish your questionnaire.

- For example, an interpretation might be “there are five 7-point Likert scale questions…point values are added across all five items for each participant…and scores below 10 indicate the participant has low self-esteem”

- Don’t introduce other variables into the mix here. All we are concerned with is how you will measure each variable by itself. The connection between variables is done using statistical tests, not operational definitions.

- Detail any validity or reliability issues uncovered by previous researchers using the same measures. If you have concerns about validity and reliability, note them, as well.

TRACK 2 (IF YOU AREN’T CREATING A RESEARCH PROPOSAL FOR THIS CLASS)

You are interested in researching the decision-making processes of parents of elementary-aged children during the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020. Specifically, you want to if and how parents’ socioeconomic class impacted their decisions about whether to send their children to school in-person or instead opt for online classes or homeschooling.

- Create a working research question for this topic.

- What is the dependent variable in this research question? The independent variable? What other variables might you want to control?

For the independent variable, dependent variable, and at least one control variable from your list:

- What measure (the specific question and answers) might you use for each one? Write out a first draft based on what you read in this section.

If you completed the exercise above and listed out all of the questions and answer choices you will use to measure the variables in your research question, you have already produced a pretty solid first draft of your questionnaire! Congrats! In essence, questionnaires are all of the self-report measures in your operational definitions for the independent, dependent, and control variables in your study arranged into one document and administered to participants. There are a few questions on a questionnaire (like name or ID#) that are not associated with the measurement of variables. These are the exception, and it’s useful to think of a questionnaire as a list of measures for variables. Of course, researchers often use more than one measure of a variable (i.e., triangulation ) so they can more confidently assert that their findings are true. A questionnaire should contain all of the measures researchers plan to collect about their variables by asking participants to self-report.

Sticking close to your operational definitions is important because it helps you avoid an everything-but-the-kitchen-sink approach that includes every possible question that occurs to you. Doing so puts an unnecessary burden on your survey respondents. Remember that you have asked your participants to give you their time and attention and to take care in responding to your questions; show them your respect by only asking questions that you actually plan to use in your analysis. For each question in your questionnaire, ask yourself how this question measures a variable in your study. An operational definition should contain the questions, response options, and how the researcher will draw conclusions about the variable based on participants’ responses.

Writing questions

So, almost all of the questions on a questionnaire are measuring some variable. For many variables, researchers will create their own questions rather than using one from another researcher. This section will provide some tips on how to create good questions to accurately measure variables in your study. First, questions should be as clear and to the point as possible. This is not the time to show off your creative writing skills; a survey is a technical instrument and should be written in a way that is as direct and concise as possible. As I’ve mentioned earlier, your survey respondents have agreed to give their time and attention to your survey. The best way to show your appreciation for their time is to not waste it. Ensuring that your questions are clear and concise will go a long way toward showing your respondents the gratitude they deserve. Pilot testing the questionnaire with friends or colleagues can help identify these issues. This process is commonly called pretesting, but to avoid any confusion with pretesting in experimental design, we refer to it as pilot testing.

Related to the point about not wasting respondents’ time, make sure that every question you pose will be relevant to every person you ask to complete it. This means two things: first, that respondents have knowledge about whatever topic you are asking them about, and second, that respondents have experienced the events, behaviors, or feelings you are asking them to report. If you are asking participants for second-hand knowledge—asking clinicians about clients’ feelings, asking teachers about students’ feelings, and so forth—you may want to clarify that the variable you are asking about is the key informant’s perception of what is happening in the target population. A well-planned sampling approach ensures that participants are the most knowledgeable population to complete your survey.

If you decide that you do wish to include questions about matters with which only a portion of respondents will have had experience, make sure you know why you are doing so. For example, if you are asking about MSW student study patterns, and you decide to include a question on studying for the social work licensing exam, you may only have a small subset of participants who have begun studying for the graduate exam or took the bachelor’s-level exam. If you decide to include this question that speaks to a minority of participants’ experiences, think about why you are including it. Are you interested in how studying for class and studying for licensure differ? Are you trying to triangulate study skills measures? Researchers should carefully consider whether questions relevant to only a subset of participants is likely to produce enough valid responses for quantitative analysis.

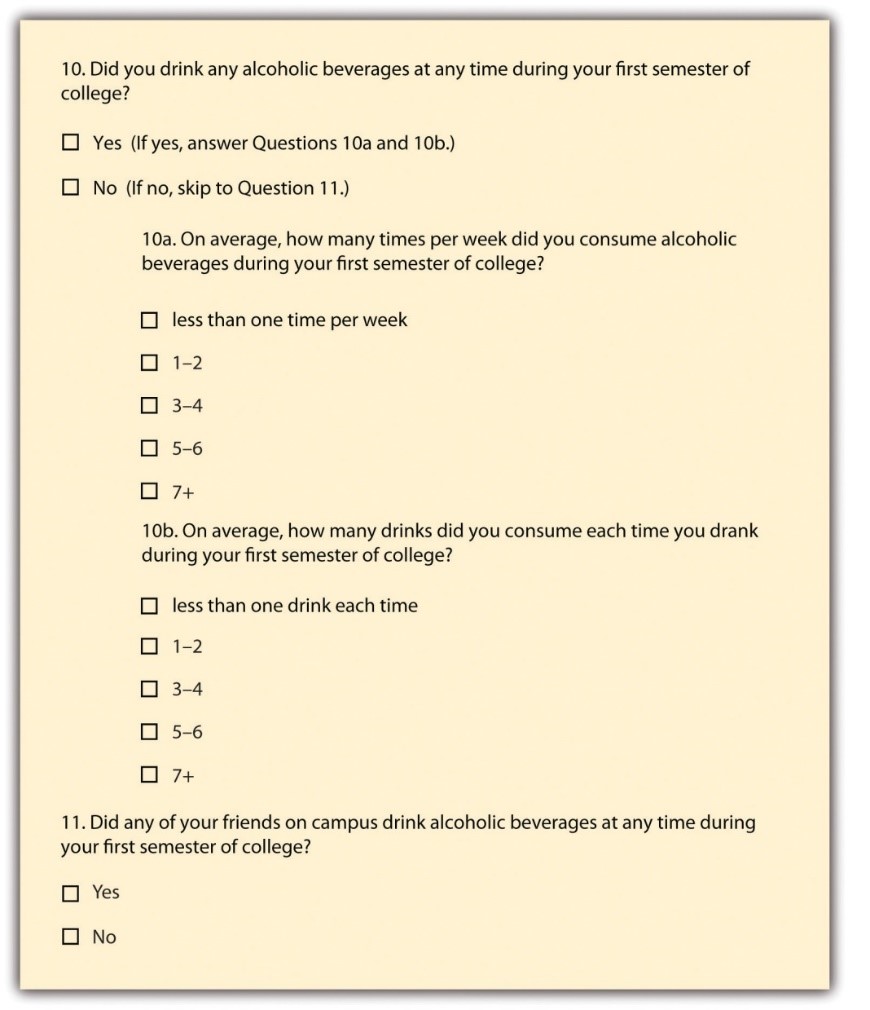

Many times, questions that are relevant to a subsample of participants are conditional on an answer to a previous question. A participant might select that they rent their home, and as a result, you might ask whether they carry renter’s insurance. That question is not relevant to homeowners, so it would be wise not to ask them to respond to it. In that case, the question of whether someone rents or owns their home is a filter question , designed to identify some subset of survey respondents who are asked additional questions that are not relevant to the entire sample. Figure 13.1 presents an example of how to accomplish this on a paper survey by adding instructions to the participant that indicate what question to proceed to next based on their response to the first one. Using online survey tools, researchers can use filter questions to only present relevant questions to participants.

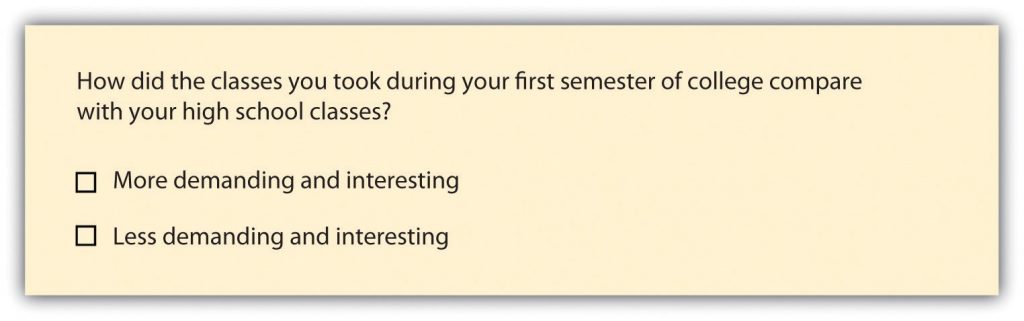

Researchers should eliminate questions that ask about things participants don’t know to minimize confusion. Assuming the question is relevant to the participant, other sources of confusion come from how the question is worded. The use of negative wording can be a source of potential confusion. Taking the question from Figure 13.1 about drinking as our example, what if we had instead asked, “Did you not abstain from drinking during your first semester of college?” This is a double negative, and it’s not clear how to answer the question accurately. It is a good idea to avoid negative phrasing, when possible. For example, “did you not drink alcohol during your first semester of college?” is less clear than “did you drink alcohol your first semester of college?”

Another 877777771`issue arises when you use jargon, or technical language, that people do not commonly know. For example, if you asked adolescents how they experience imaginary audience , they would find it difficult to link those words to the concepts from David Elkind’s theory. The words you use in your questions must be understandable to your participants. If you find yourself using jargon or slang, break it down into terms that are more universal and easier to understand.

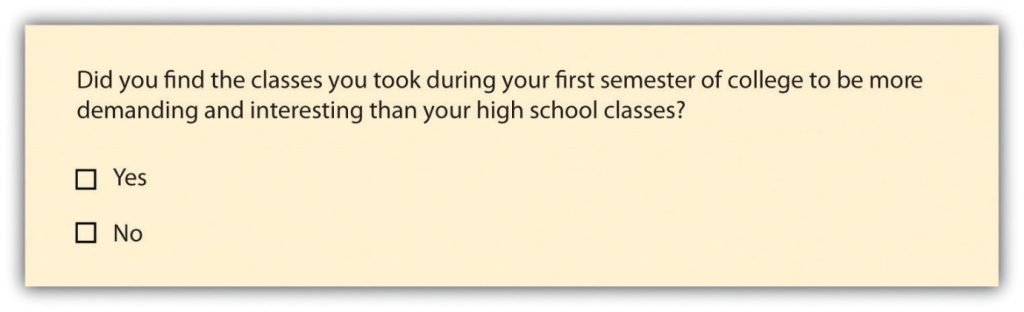

Asking multiple questions as though they are a single question can also confuse survey respondents. There’s a specific term for this sort of question; it is called a double-barreled question . Figure 13.2 shows a double-barreled question. Do you see what makes the question double-barreled? How would someone respond if they felt their college classes were more demanding but also more boring than their high school classes? Or less demanding but more interesting? Because the question combines “demanding” and “interesting,” there is no way to respond yes to one criterion but no to the other.

Another thing to avoid when constructing survey questions is the problem of social desirability . We all want to look good, right? And we all probably know the politically correct response to a variety of questions whether we agree with the politically correct response or not. In survey research, social desirability refers to the idea that respondents will try to answer questions in a way that will present them in a favorable light. (You may recall we covered social desirability bias in Chapter 11. )

Perhaps we decide that to understand the transition to college, we need to know whether respondents ever cheated on an exam in high school or college for our research project. We all know that cheating on exams is generally frowned upon (at least I hope we all know this). So, it may be difficult to get people to admit to cheating on a survey. But if you can guarantee respondents’ confidentiality, or even better, their anonymity, chances are much better that they will be honest about having engaged in this socially undesirable behavior. Another way to avoid problems of social desirability is to try to phrase difficult questions in the most benign way possible. Earl Babbie (2010) [1] offers a useful suggestion for helping you do this—simply imagine how you would feel responding to your survey questions. If you would be uncomfortable, chances are others would as well.

Try to step outside your role as researcher for a second, and imagine you were one of your participants. Evaluate the following:

- Is the question too general? Sometimes, questions that are too general may not accurately convey respondents’ perceptions. If you asked someone how they liked a certain book and provide a response scale ranging from “not at all” to “extremely well”, and if that person selected “extremely well,” what do they mean? Instead, ask more specific behavioral questions, such as “Will you recommend this book to others?” or “Do you plan to read other books by the same author?”

- Is the question too detailed? Avoid unnecessarily detailed questions that serve no specific research purpose. For instance, do you need the age of each child in a household or is just the number of children in the household acceptable? However, if unsure, it is better to err on the side of details than generality.

- Is the question presumptuous? Does your question make assumptions? For instance, if you ask, “what do you think the benefits of a tax cut would be?” you are presuming that the participant sees the tax cut as beneficial. But many people may not view tax cuts as beneficial. Some might see tax cuts as a precursor to less funding for public schools and fewer public services such as police, ambulance, and fire department. Avoid questions with built-in presumptions.

- Does the question ask the participant to imagine something? Is the question imaginary? A popular question on many television game shows is “if you won a million dollars on this show, how will you plan to spend it?” Most participants have never been faced with this large amount of money and have never thought about this scenario. In fact, most don’t even know that after taxes, the value of the million dollars will be greatly reduced. In addition, some game shows spread the amount over a 20-year period. Without understanding this “imaginary” situation, participants may not have the background information necessary to provide a meaningful response.

Try to step outside your role as researcher for a second, and imagine you were one of your participants. Use the following prompts to evaluate your draft questions from the previous exercise:

Cultural considerations

When researchers write items for questionnaires, they must be conscientious to avoid culturally biased questions that may be inappropriate or difficult for certain populations.

[insert information related to asking about demographics and how this might make some people uncomfortable based on their identity(ies) and how to potentially address]

You should also avoid using terms or phrases that may be regionally or culturally specific (unless you are absolutely certain all your respondents come from the region or culture whose terms you are using). When I first moved to southwest Virginia, I didn’t know what a holler was. Where I grew up in New Jersey, to holler means to yell. Even then, in New Jersey, we shouted and screamed, but we didn’t holler much. In southwest Virginia, my home at the time, a holler also means a small valley in between the mountains. If I used holler in that way on my survey, people who live near me may understand, but almost everyone else would be totally confused.

Testing questionnaires before using them

Finally, it is important to get feedback on your survey questions from as many people as possible, especially people who are like those in your sample. Now is not the time to be shy. Ask your friends for help, ask your mentors for feedback, ask your family to take a look at your survey as well. The more feedback you can get on your survey questions, the better the chances that you will come up with a set of questions that are understandable to a wide variety of people and, most importantly, to those in your sample.

In sum, in order to pose effective survey questions, researchers should do the following:

- Identify how each question measures an independent, dependent, or control variable in their study.

- Keep questions clear and succinct.

- Make sure respondents have relevant lived experience to provide informed answers to your questions.

- Use filter questions to avoid getting answers from uninformed participants.

- Avoid questions that are likely to confuse respondents—including those that use double negatives, use culturally specific terms or jargon, and pose more than one question at a time.

- Imagine how respondents would feel responding to questions.

- Get feedback, especially from people who resemble those in the researcher’s sample.

Table 13.1 offers one model for writing effective questionnaire items.

Let’s complete a first draft of your questions.

- In the first exercise, you wrote out the questions and answers for each measure of your independent and dependent variables. Evaluate each question using the criteria listed above on effective survey questions.

- Type out questions for your control variables and evaluate them, as well. Consider what response options you want to offer participants.

Now, let’s revise any questions that do not meet your standards!

- Use the BRUSO model in Table 13.1 for an illustration of how to address deficits in question wording. Keep in mind that you are writing a first draft in this exercise, and it will take a few drafts and revisions before your questions are ready to distribute to participants.

- In the first exercise, you wrote out the question and answers for your independent, dependent, and at least one control variable. Evaluate each question using the criteria listed above on effective survey questions.

- Use the BRUSO model in Table 13.1 for an illustration of how to address deficits in question wording. In real research, it will take a few drafts and revisions before your questions are ready to distribute to participants.

Writing response options

While posing clear and understandable questions in your survey is certainly important, so too is providing respondents with unambiguous response options. Response options are the answers that you provide to the people completing your questionnaire. Generally, respondents will be asked to choose a single (or best) response to each question you pose. We call questions in which the researcher provides all of the response options closed-ended questions . Keep in mind, closed-ended questions can also instruct respondents to choose multiple response options, rank response options against one another, or assign a percentage to each response option. But be cautious when experimenting with different response options! Accepting multiple responses to a single question may add complexity when it comes to quantitatively analyzing and interpreting your data.

Surveys need not be limited to closed-ended questions. Sometimes survey researchers include open-ended questions in their survey instruments as a way to gather additional details from respondents. An open-ended question does not include response options; instead, respondents are asked to reply to the question in their own way, using their own words. These questions are generally used to find out more about a survey participant’s experiences or feelings about whatever they are being asked to report in the survey. If, for example, a survey includes closed-ended questions asking respondents to report on their involvement in extracurricular activities during college, an open-ended question could ask respondents why they participated in those activities or what they gained from their participation. While responses to such questions may also be captured using a closed-ended format, allowing participants to share some of their responses in their own words can make the experience of completing the survey more satisfying to respondents and can also reveal new motivations or explanations that had not occurred to the researcher. This is particularly important for mixed-methods research. It is possible to analyze open-ended response options quantitatively using content analysis (i.e., counting how often a theme is represented in a transcript looking for statistical patterns). However, for most researchers, qualitative data analysis will be needed to analyze open-ended questions, and researchers need to think through how they will analyze any open-ended questions as part of their data analysis plan. Open-ended questions cannot be operationally defined because you don’t know what responses you will get. We will address qualitative data analysis in greater detail in Chapter 19.

To write an effective response options for closed-ended questions, there are a couple of guidelines worth following. First, be sure that your response options are mutually exclusive . Look back at Figure 13.1, which contains questions about how often and how many drinks respondents consumed. Do you notice that there are no overlapping categories in the response options for these questions? This is another one of those points about question construction that seems fairly obvious but that can be easily overlooked. Response options should also be exhaustive . In other words, every possible response should be covered in the set of response options that you provide. For example, note that in question 10a in Figure 13.1, we have covered all possibilities—those who drank, say, an average of once per month can choose the first response option (“less than one time per week”) while those who drank multiple times a day each day of the week can choose the last response option (“7+”). All the possibilities in between these two extremes are covered by the middle three response options, and every respondent fits into one of the response options we provided.

Earlier in this section, we discussed double-barreled questions. Response options can also be double barreled, and this should be avoided. Figure 13.3 is an example of a question that uses double-barreled response options. Other tips about questions are also relevant to response options, including that participants should be knowledgeable enough to select or decline a response option as well as avoiding jargon and cultural idioms.

Even if you phrase questions and response options clearly, participants are influenced by how many response options are presented on the questionnaire. For Likert scales, five or seven response options generally allow about as much precision as respondents are capable of. However, numerical scales with more options can sometimes be appropriate. For dimensions such as attractiveness, pain, and likelihood, a 0-to-10 scale will be familiar to many respondents and easy for them to use. Regardless of the number of response options, the most extreme ones should generally be “balanced” around a neutral or modal midpoint. An example of an unbalanced rating scale measuring perceived likelihood might look like this:

Unlikely | Somewhat Likely | Likely | Very Likely | Extremely Likely

Because we have four rankings of likely and only one ranking of unlikely, the scale is unbalanced and most responses will be biased toward “likely” rather than “unlikely.” A balanced version might look like this:

Extremely Unlikely | Somewhat Unlikely | As Likely as Not | Somewhat Likely | Extremely Likely

In this example, the midpoint is halfway between likely and unlikely. Of course, a middle or neutral response option does not have to be included. Researchers sometimes choose to leave it out because they want to encourage respondents to think more deeply about their response and not simply choose the middle option by default. Fence-sitters are respondents who choose neutral response options, even if they have an opinion. Some people will be drawn to respond, “no opinion” even if they have an opinion, particularly if their true opinion is the not a socially desirable opinion. Floaters , on the other hand, are those that choose a substantive answer to a question when really, they don’t understand the question or don’t have an opinion.

As you can see, floating is the flip side of fence-sitting. Thus, the solution to one problem is often the cause of the other. How you decide which approach to take depends on the goals of your research. Sometimes researchers specifically want to learn something about people who claim to have no opinion. In this case, allowing for fence-sitting would be necessary. Other times researchers feel confident their respondents will all be familiar with every topic in their survey. In this case, perhaps it is okay to force respondents to choose one side or another (e.g., agree or disagree) without a middle option (e.g., neither agree nor disagree) or to not include an option like “don’t know enough to say” or “not applicable.” There is no always-correct solution to either problem. But in general, including middle option in a response set provides a more exhaustive set of response options than one that excludes one.

==This came from 10.3 under “Measuring unidimensional concepts” but it seems more appropriate in the chapter about writing survey questions. We need to make sure this section flows well. Maybe there should be a better organized subsection on rating scales? Where does this go? Does it need any revision?===

The number of response options on a typical rating scale is usually five or seven, though it can range from three to 11. Five-point scales are best for unipolar scales where only one construct is tested, such as frequency (Never, Rarely, Sometimes, Often, Always). Seven-point scales are best for bipolar scales where there is a dichotomous spectrum, such as liking (Like very much, Like somewhat, Like slightly, Neither like nor dislike, Dislike slightly, Dislike somewhat, Dislike very much). For bipolar questions, it is useful to offer an earlier question that branches them into an area of the scale; if asking about liking ice cream, first ask “Do you generally like or dislike ice cream?” Once the respondent chooses like or dislike, refine it by offering them relevant choices from the seven-point scale. Branching improves both reliability and validity (Krosnick & Berent, 1993). [2] Although you often see scales with numerical labels, it is best to only present verbal labels to the respondents but convert them to numerical values in the analyses. Avoid partial labels or length or overly specific labels. In some cases, the verbal labels can be supplemented with (or even replaced by) meaningful graphics. The last rating scale shown in Figure 10.1 is a visual-analog scale, on which participants make a mark somewhere along the horizontal line to indicate the magnitude of their response.

Finalizing Response Options

The most important check before your finalize your response options is to align them with your operational definitions. As we’ve discussed before, your operational definitions include your measures (questions and responses options) as well as how to interpret those measures in terms of the variable being measured. In particular, you should be able to interpret all response options to a question based on your operational definition of the variable it measures. If you wanted to measure the variable “social class,” you might ask one question about a participant’s annual income and another about family size. Your operational definition would need to provide clear instructions on how to interpret response options. Your operational definition is basically like this social class calculator from Pew Research , though they include a few more questions in their definition.

To drill down a bit more, as Pew specifies in the section titled “how the income calculator works,” the interval/ratio data respondents enter is interpreted using a formula combining a participant’s four responses to the questions posed by Pew categorizing their household into three categories—upper, middle, or lower class. So, the operational definition includes the four questions comprising the measure and the formula or interpretation which converts responses into the three final categories that we are familiar with: lower, middle, and upper class.

It’s perfectly normal for operational definitions to change levels of measurement, and it’s also perfectly normal for the level of measurement to stay the same. The important thing is that each response option a participant can provide is accounted for by the operational definition. Throw any combination of family size, location, or income at the Pew calculator, and it will define you into one of those three social class categories.

Unlike Pew’s definition, the operational definitions in your study may not need their own webpage to define and describe. For many questions and answers, interpreting response options is easy. If you were measuring “income” instead of “social class,” you could simply operationalize the term by asking people to list their total household income before taxes are taken out. Higher values indicate higher income, and lower values indicate lower income. Easy. Regardless of whether your operational definitions are simple or more complex, every response option to every question on your survey (with a few exceptions) should be interpretable using an operational definition of a variable. Just like we want to avoid an everything-but-the-kitchen-sink approach to questions on our questionnaire, you want to make sure your final questionnaire only contains response options that you will use in your study.

One note of caution on interpretation (sorry for repeating this). We want to remind you again that an operational definition should not mention more than one variable. In our example above, your operational definition could not say “a family of three making under $50,000 is lower class; therefore, they are more likely to experience food insecurity.” That last clause about food insecurity may well be true, but it’s not a part of the operational definition for social class. Each variable (food insecurity and class) should have its own operational definition. If you are talking about how to interpret the relationship between two variables, you are talking about your data analysis plan . We will discuss how to create your data analysis plan beginning in Chapter 14 . For now, one consideration is that depending on the statistical test you use to test relationships between variables, you may need nominal, ordinal, or interval/ratio data. Your questions and response options should match the level of measurement you need with the requirements of the specific statistical tests in your data analysis plan. Once you finalize your data analysis plan, return to your questionnaire to confirm the level of measurement matches with the statistical test you’ve chosen.

In summary, to write effective response options researchers should do the following:

- Avoid wording that is likely to confuse respondents—including double negatives, use culturally specific terms or jargon, and double-barreled response options.

- Ensure response options are relevant to participants’ knowledge and experience so they can make an informed and accurate choice.

- Present mutually exclusive and exhaustive response options.

- Consider fence-sitters and floaters, and the use of neutral or “not applicable” response options.

- Define how response options are interpreted as part of an operational definition of a variable.

- Check level of measurement matches operational definitions and the statistical tests in the data analysis plan (once you develop one in the future)

Look back at the response options you drafted in the previous exercise. Make sure you have a first draft of response options for each closed-ended question on your questionnaire.

- Using the criteria above, evaluate the wording of the response options for each question on your questionnaire.

- Revise your questions and response options until you have a complete first draft.

- Do your first read-through and provide a dummy answer to each question. Make sure you can link each response option and each question to an operational definition.

Look back at the response options you drafted in the previous exercise.

From this discussion, we hope it is clear why researchers using quantitative methods spell out all of their plans ahead of time. Ultimately, there should be a straight line from operational definition through measures on your questionnaire to the data analysis plan. If your questionnaire includes response options that are not aligned with operational definitions or not included in the data analysis plan, the responses you receive back from participants won’t fit with your conceptualization of the key variables in your study. If you do not fix these errors and proceed with collecting unstructured data, you will lose out on many of the benefits of survey research and face overwhelming challenges in answering your research question.

Designing questionnaires

Based on your work in the previous section, you should have a first draft of the questions and response options for the key variables in your study. Now, you’ll also need to think about how to present your written questions and response options to survey respondents. It’s time to write a final draft of your questionnaire and make it look nice. Designing questionnaires takes some thought. First, consider the route of administration for your survey. What we cover in this section will apply equally to paper and online surveys, but if you are planning to use online survey software, you should watch tutorial videos and explore the features of of the survey software you will use.

Informed consent & instructions

Writing effective items is only one part of constructing a survey. For one thing, every survey should have a written or spoken introduction that serves two basic functions (Peterson, 2000) . [3] One is to encourage respondents to participate in the survey. In many types of research, such encouragement is not necessary either because participants do not know they are in a study (as in naturalistic observation) or because they are part of a subject pool and have already shown their willingness to participate by signing up and showing up for the study. Survey research usually catches respondents by surprise when they answer their phone, go to their mailbox, or check their e-mail—and the researcher must make a good case for why they should agree to participate. Thus, the introduction should briefly explain the purpose of the survey and its importance, provide information about the sponsor of the survey (university-based surveys tend to generate higher response rates), acknowledge the importance of the respondent’s participation, and describe any incentives for participating.

The second function of the introduction is to establish informed consent . Remember that this involves describing to respondents everything that might affect their decision to participate. This includes the topics covered by the survey, the amount of time it is likely to take, the respondent’s option to withdraw at any time, confidentiality issues, and other ethical considerations we covered in Chapter 6. Written consent forms are not always used in survey research (when the research is of minimal risk and completion of the survey instrument is often accepted by the IRB as evidence of consent to participate), so it is important that this part of the introduction be well documented and presented clearly and in its entirety to every respondent.

Organizing items to be easy and intuitive to follow

The introduction should be followed by the substantive questionnaire items. But first, it is important to present clear instructions for completing the questionnaire, including examples of how to use any unusual response scales. Remember that the introduction is the point at which respondents are usually most interested and least fatigued, so it is good practice to start with the most important items for purposes of the research and proceed to less important items. Items should also be grouped by topic or by type. For example, items using the same rating scale (e.g., a 5-point agreement scale) should be grouped together if possible to make things faster and easier for respondents. Demographic items are often presented last. This can be because they are easy to answer in the event respondents have become tired or bored, because they are least interesting to participants, or because they can raise concerns for respondents from marginalized groups who may see questions about their identities as a potential red flag. Of course, any survey should end with an expression of appreciation to the respondent.

Questions are often organized thematically. If our survey were measuring social class, perhaps we’d have a few questions asking about employment, others focused on education, and still others on housing and community resources. Those may be the themes around which we organize our questions. Or perhaps it would make more sense to present any questions we had about parents’ income and then present a series of questions about estimated future income. Grouping by theme is one way to be deliberate about how you present your questions. Keep in mind that you are surveying people, and these people will be trying to follow the logic in your questionnaire. Jumping from topic to topic can give people a bit of whiplash and may make participants less likely to complete it.

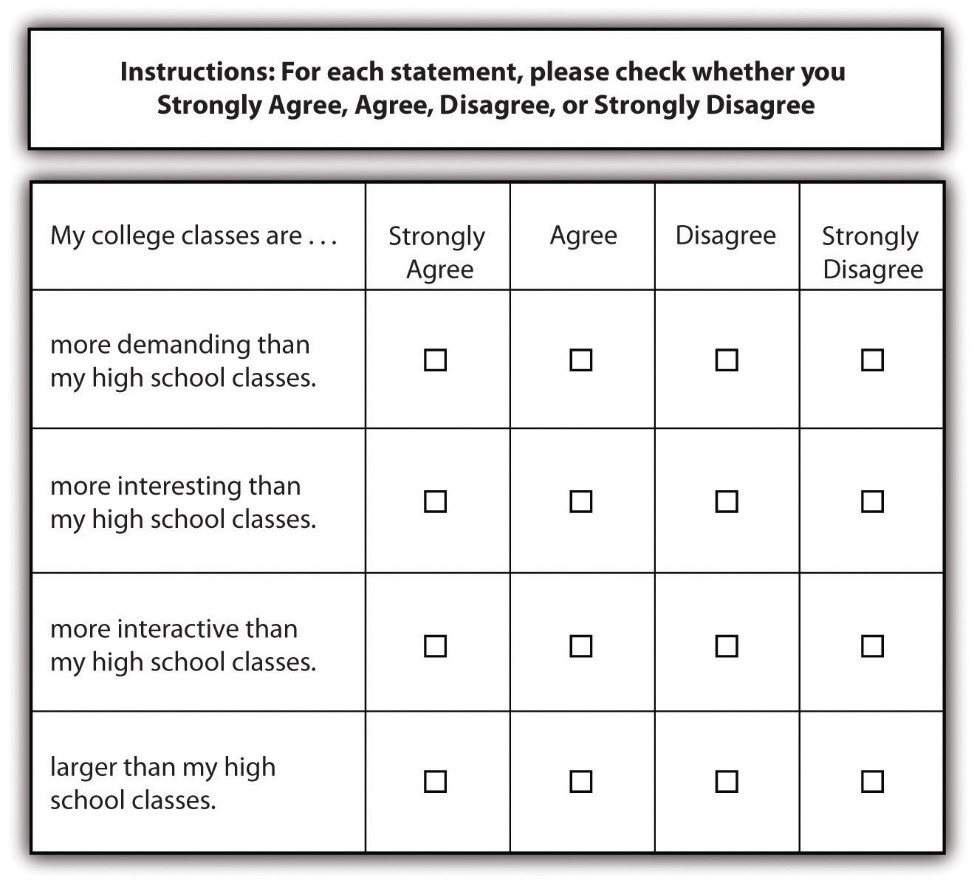

Using a matrix is a nice way of streamlining response options for similar questions. A matrix is a question type that lists a set of questions for which the answer categories are all the same. If you have a set of questions for which the response options are the same, it may make sense to create a matrix rather than posing each question and its response options individually. Not only will this save you some space in your survey but it will also help respondents progress through your survey more easily. A sample matrix can be seen in Figure 13.4.

Once you have grouped similar questions together, you’ll need to think about the order in which to present those question groups. Most survey researchers agree that it is best to begin a survey with questions that will want to make respondents continue (Babbie, 2010; Dillman, 2000; Neuman, 2003). [4] In other words, don’t bore respondents, but don’t scare them away either. There’s some disagreement over where on a survey to place demographic questions, such as those about a person’s age, gender, and race. On the one hand, placing them at the beginning of the questionnaire may lead respondents to think the survey is boring, unimportant, and not something they want to bother completing. On the other hand, if your survey deals with some very sensitive topic, such as child sexual abuse or criminal convictions, you don’t want to scare respondents away or shock them by beginning with your most intrusive questions.

Your participants are human. They will react emotionally to questionnaire items, and they will also try to uncover your research questions and hypotheses. In truth, the order in which you present questions on a survey is best determined by the unique characteristics of your research. When feasible, you should consult with key informants from your target population determine how best to order your questions. If it is not feasible to do so, think about the unique characteristics of your topic, your questions, and most importantly, your sample. Keeping in mind the characteristics and needs of the people you will ask to complete your survey should help guide you as you determine the most appropriate order in which to present your questions. None of your decisions will be perfect, and all studies have limitations.

Questionnaire length

You’ll also need to consider the time it will take respondents to complete your questionnaire. Surveys vary in length, from just a page or two to a dozen or more pages, which means they also vary in the time it takes to complete them. How long to make your survey depends on several factors. First, what is it that you wish to know? Wanting to understand how grades vary by gender and year in school certainly requires fewer questions than wanting to know how people’s experiences in college are shaped by demographic characteristics, college attended, housing situation, family background, college major, friendship networks, and extracurricular activities. Keep in mind that even if your research question requires a sizable number of questions be included in your questionnaire, do your best to keep the questionnaire as brief as possible. Any hint that you’ve thrown in a bunch of useless questions just for the sake of it will turn off respondents and may make them not want to complete your survey.

Second, and perhaps more important, how long are respondents likely to be willing to spend completing your questionnaire? If you are studying college students, asking them to use their very limited time to complete your survey may mean they won’t want to spend more than a few minutes on it. But if you ask them to complete your survey during down-time between classes and there is little work to be done, students may be willing to give you a bit more of their time. Think about places and times that your sampling frame naturally gathers and whether you would be able to either recruit participants or distribute a survey in that context. Estimate how long your participants would reasonably have to complete a survey presented to them during this time. The more you know about your population (such as what weeks have less work and more free time), the better you can target questionnaire length.

The time that survey researchers ask respondents to spend on questionnaires varies greatly. Some researchers advise that surveys should not take longer than about 15 minutes to complete (as cited in Babbie 2010), [5] whereas others suggest that up to 20 minutes is acceptable (Hopper, 2010). [6] As with question order, there is no clear-cut, always-correct answer about questionnaire length. The unique characteristics of your study and your sample should be considered to determine how long to make your questionnaire. For example, if you planned to distribute your questionnaire to students in between classes, you will need to make sure it is short enough to complete before the next class begins.

When designing a questionnaire, a researcher should consider:

- Weighing strengths and limitations of the method of delivery, including the advanced tools in online survey software or the simplicity of paper questionnaires.

- Grouping together items that ask about the same thing.

- Moving any questions about sensitive items to the end of the questionnaire, so as not to scare respondents off.

- Moving any questions that engage the respondent to answer the questionnaire at the beginning, so as not to bore them.

- Timing the length of the questionnaire with a reasonable length of time you can ask of your participants.

- Dedicating time to visual design and ensure the questionnaire looks professional.

Type out a final draft of your questionnaire in a word processor or online survey tool.

- Evaluate your questionnaire using the guidelines above, revise it, and get it ready to share with other student researchers.

- Take a look at the question drafts you have completed and decide on an order for your questions. E valuate your draft questionnaire using the guidelines above, and revise as needed.

Pilot testing and revising questionnaires

A good way to estimate the time it will take respondents to complete your questionnaire (and other potential challenges) is through pilot testing . Pilot testing allows you to get feedback on your questionnaire so you can improve it before you actually administer it. It can be quite expensive and time consuming if you wish to pilot test your questionnaire on a large sample of people who very much resemble the sample to whom you will eventually administer the finalized version of your questionnaire. But you can learn a lot and make great improvements to your questionnaire simply by pilot testing with a small number of people to whom you have easy access (perhaps you have a few friends who owe you a favor). By pilot testing your questionnaire, you can find out how understandable your questions are, get feedback on question wording and order, find out whether any of your questions are boring or offensive, and learn whether there are places where you should have included filter questions. You can also time pilot testers as they take your survey. This will give you a good idea about the estimate to provide respondents when you administer your survey and whether you have some wiggle room to add additional items or need to cut a few items.

Perhaps this goes without saying, but your questionnaire should also have an attractive design. A messy presentation style can confuse respondents or, at the very least, annoy them. Be brief, to the point, and as clear as possible. Avoid cramming too much into a single page. Make your font size readable (at least 12 point or larger, depending on the characteristics of your sample), leave a reasonable amount of space between items, and make sure all instructions are exceptionally clear. If you are using an online survey, ensure that participants can complete it via mobile, computer, and tablet devices. Think about books, documents, articles, or web pages that you have read yourself—which were relatively easy to read and easy on the eyes and why? Try to mimic those features in the presentation of your survey questions. While online survey tools automate much of visual design, word processors are designed for writing all kinds of documents and may need more manual adjustment as part of visual design.

Realistically, your questionnaire will continue to evolve as you develop your data analysis plan over the next few chapters. By now, you should have a complete draft of your questionnaire grounded in an underlying logic that ties together each question and response option to a variable in your study. Once your questionnaire is finalized, you will need to submit it for ethical approval from your IRB. If your study requires IRB approval, it may be worthwhile to submit your proposal before your questionnaire is completely done. Revisions to IRB protocols are common and it takes less time to review a few changes to questions and answers than it does to review the entire study, so give them the whole study as soon as you can. Once the IRB approves your questionnaire, you cannot change it without their okay.

Key Takeaways

- A questionnaire is comprised of self-report measures of variables in a research study.

- Make sure your survey questions will be relevant to all respondents and that you use filter questions when necessary.

- Effective survey questions and responses take careful construction by researchers, as participants may be confused or otherwise influenced by how items are phrased.

- The questionnaire should start with informed consent and instructions, flow logically from one topic to the next, engage but not shock participants, and thank participants at the end.

- Pilot testing can help identify any issues in a questionnaire before distributing it to participants, including language or length issues.

It’s a myth that researchers work alone! Get together with a few of your fellow students and swap questionnaires for pilot testing.

- Use the criteria in each section above (questions, response options, questionnaires) and provide your peers with the strengths and weaknesses of their questionnaires.

- See if you can guess their research question and hypothesis based on the questionnaire alone.

It’s a myth that researchers work alone! Get together with a few of your fellow students and compare draft questionnaires.

- What are the strengths and limitations of your questionnaire as compared to those of your peers?

- Is there anything you would like to use from your peers’ questionnaires in your own?

- Babbie, E. (2010). The practice of social research (12th ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth. ↵

- Krosnick, J.A. & Berent, M.K. (1993). Comparisons of party identification and policy preferences: The impact of survey question format. American Journal of Political Science, 27(3), 941-964. ↵

- Peterson, R. A. (2000). Constructing effective questionnaires . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. ↵

- Babbie, E. (2010). The practice of social research (12th ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth; Dillman, D. A. (2000). Mail and Internet surveys: The tailored design method (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Wiley; Neuman, W. L. (2003). Social research methods: Qualitative and quantitative approaches (5th ed.). Boston, MA: Pearson. ↵

- Babbie, E. (2010). The practice of social research (12th ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth. ↵

- Hopper, J. (2010). How long should a survey be? Retrieved from http://www.verstaresearch.com/blog/how-long-should-a-survey-be ↵

According to the APA Dictionary of Psychology, an operational definition is "a description of something in terms of the operations (procedures, actions, or processes) by which it could be observed and measured. For example, the operational definition of anxiety could be in terms of a test score, withdrawal from a situation, or activation of the sympathetic nervous system. The process of creating an operational definition is known as operationalization."

Triangulation of data refers to the use of multiple types, measures or sources of data in a research project to increase the confidence that we have in our findings.

Testing out your research materials in advance on people who are not included as participants in your study.

items on a questionnaire designed to identify some subset of survey respondents who are asked additional questions that are not relevant to the entire sample

a question that asks more than one thing at a time, making it difficult to respond accurately

When a participant answers in a way that they believe is socially the most acceptable answer.

the answers researchers provide to participants to choose from when completing a questionnaire

questions in which the researcher provides all of the response options

Questions for which the researcher does not include response options, allowing for respondents to answer the question in their own words

respondents to a survey who choose neutral response options, even if they have an opinion

respondents to a survey who choose a substantive answer to a question when really, they don’t understand the question or don’t have an opinion

An ordered outline that includes your research question, a description of the data you are going to use to answer it, and the exact analyses, step-by-step, that you plan to run to answer your research question.

A process through which the researcher explains the research process, procedures, risks and benefits to a potential participant, usually through a written document, which the participant than signs, as evidence of their agreement to participate.

a type of survey question that lists a set of questions for which the response options are all the same in a grid layout

Doctoral Research Methods in Social Work Copyright © by Mavs Open Press. All Rights Reserved.

Share This Book

Root out friction in every digital experience, super-charge conversion rates, and optimize digital self-service

Uncover insights from any interaction, deliver AI-powered agent coaching, and reduce cost to serve

Increase revenue and loyalty with real-time insights and recommendations delivered to teams on the ground

Know how your people feel and empower managers to improve employee engagement, productivity, and retention

Take action in the moments that matter most along the employee journey and drive bottom line growth

Whatever they’re are saying, wherever they’re saying it, know exactly what’s going on with your people

Get faster, richer insights with qual and quant tools that make powerful market research available to everyone

Run concept tests, pricing studies, prototyping + more with fast, powerful studies designed by UX research experts

Track your brand performance 24/7 and act quickly to respond to opportunities and challenges in your market

Explore the platform powering Experience Management

- Free Account

- Product Demos

- For Digital

- For Customer Care