Helping Writers Become Authors

Write your best story. Change your life. Astound the world.

- Start Here!

- Story Structure Database

- Outlining Your Novel

- Story Structure

- Character Arcs

- Archetypal Characters

- Scene Structure

- Common Writing Mistakes

- Storytelling According to Marvel

- K.M. Weiland Site

Most Common Writing Mistakes, Pt. 58: Too Much Description

The bad news is that this is a big deal in narrative fiction. Get the balance of your description wrong, and it could throw off your entire story.

The good news is that once you understand how to examine and execute your descriptions, you will have taken your writing to the next level.

I’ve talked previously about the problems of too little (or, worse, no ) description . Today, we’re going to examine what is perhaps the even more egregious side of this dilemma: too much description.

2 Reasons Readers Hate Too Much Description

While some authors may err too far on the other side and leave the entire visual world of their stories to their subtext, others among us might err too far in the opposite direction.

Not only do we give readers the descriptive details they need , we belabor the point by telling them every little last detail—about the way every cranny of a setting looks, and not only how it looks today , but how it looked in years past and maybe even how it’s going to look in the future.

The problem here is twofold:

1. Lengthy descriptions are almost inevitably boring.

2. They’re boring because they do not matter .

Readers are very trusting and obliging people. They will follow you anywhere and listen to anything you have to say as long as there’s a point . This is true of the story in general, each scene within that story, right on down to every word choice.

He who is faithful in a very little thing is faithful also in much.

This holds true in storytelling as well. If you’re reading a book and the author can’t prove himself in something so small as the word choices in his descriptions, then it’s highly unlikely he’s going to offer mastery in the bigger-picture areas of structure, arc, and theme.

Why Too Much Description Actually Pushes Readers Out of Your Story

The reason readers instinctively understand too much description is problematic is because it signals a deeper issue within the framework of the story. Namely, too much description saps the story of subtext .

Authors must find the perfect balance of telling readers just enough for the story to make sense and come to life, without sharing so much that readers are crowded right out of the story. Our goal as storytellers should be to create a partnership between our own imaginations and that of our readers’ . If we’re describing every little detail—both pertinent and not—what we’re creating instead is an on-the-nose narrative that has literally been described to death.

Why You Might Be Accidentally Using Too Much Description

There are generally three reasons an author might slip into the trap of using too much description.

1. You Aren’t Trusting Readers to “Get” It

Authors often get nervous about their abilities. They aren’t sure they’ve chosen the right quantity or quality of “telling” details to bring the scene to life for readers. So they pile on more descriptors and still more.

Overwriting is just fine in the beginning . In fact, sometimes it’s helpful to purposefully overwrite to help you dig deep and find the best descriptors. But you must be wise enough and brave enough to pare back descriptions to their essence. When in doubt, pare it back as much as you dare, then bring in an objective reader to tell you if everything still makes sense.

2. You Love Your Story Details Too Much

Nobody is ever going to love your story more than you do. You love everything about it. You love the very specific pattern of wear on your protagonist’s bedroom carpet. You love your sidekick’s freckles so much you’ve counted every last one of them. You love your heroine’s opulent, gorgeous, and very expansive wardrobe. Naturally , you want to share every one of these awesomesauce details with readers, because of course they’re going to find them just as awesome and fascinating as you do.

Except… they don’t. As I may have mentioned above, readers only care about stuff that matters—stuff that advances the plot, stuff that helps them understand the story and characters, stuff that fires their own imaginations without bogging things down.

On Writing by Stephen King (affiliate link)

As Stephen King says in On Writing :

Write with the door closed; rewrite with the door open.

In other words, once you decide to send your story out into the world for the enjoyment of readers, it doesn’t belong to you anymore and you must optimize its presentation to benefit them , not to indulge your own obsessive passion about ultimately irrelevant details.

3. You’re Still Growing Your Story Sensibilities

As with all of narrative storytelling, learning to create the proper balance of description is a process of experience. Even with the best of intentions, none of us ace it the first (or thirtieth) time out of the gate.

The first step in learning to refine your descriptions is to be aware they probably do need a little refining. Pay attention to them as you’re writing them, and particularly as you’re revising. Listen to their rhythm within the overall flow of the story. Question your word and detail choices. And, when all that is done, bring in reinforcements and ask others to pay special attention to anywhere they might find your descriptions growing tedious.

The 2 Most Common Areas to Look for Too Much Description

Ready to slay your unnecessary description wherever you can find it? Good. Let’s go find it!

For the most part, all descriptions fall into two categories: character description and setting description.

Character Description

What too much character description looks like.

I shook hands with the man. He had brown hair and brown eyes. He was six feet tall and skinny. He wore overalls and a brown suit coat. There were patches on the elbows and the knees. He also wore a hat with a hole in it. He had a mole beside his nose. His teeth were crooked. His sister stood beside him. She had red hair and blue eyes. She was five feet three and plump. She wore a dress and an apron, but no hat. Her teeth were also crooked.

What Just Enough Character Description Looks Like

The Guernsey Literary and Potato Peel Pie Society by Mary Ann Shaffer and Annie Barrows (affiliate link)

Then Dawsey held out his hands. I had been expecting him to look like Charles Lamb, and he does, a little—he has the same even gaze. He presented me with a bouquet of carnations from Booker, who couldn’t be present; he had concussed himself during a rehearsal and was in hospital overnight for observation. Dawsey is dark and wiry, and his face has a quiet, watchful look about it—until he smiles. Saving a certain sister of yours, he has the sweetest smile I’ve ever seen, and I remembered Amelia writing that he has a rare gift for persuasion—I can believe it. Like Eben—like everyone here—he is too thin, though you can tell he was more substantial once. His hair is going grey, and he has deep-set brown eyes, so dark they look black. The lines around his eyes make him seem to be starting a smile even when he’s not, but I don’t think he’s over forty. He is only a little taller than I am and limps slightly, but he’s strong—hefted all my luggage, me, Amelia, and Kit into his wagon with no trouble. (From The Guernsey Literary and Potato Peel Pie Society by Mary Ann Shaffer and Annie Barrows)

Should You Describe Your Character’s…

Blood Song by Anthony Ryan (affiliate link)

In my early books, I had a serious bent for giving all my heroines a “Grecian nose.” Honestly, I still have no idea what that even is, much less what it looks like. In general, faces are just plain hard to describe. Going into the details of forehead, jaw, lips, and nose takes up a ton of space and doesn’t generally impart too much useful knowledge to readers. Much better to do as Anthony Ryan did in his fantasy Blood Song , when he had one character comment briefly but tellingly on the protagonist’s appearance:

“I’d heard you were handsome. You’re not. But your face is interesting.”

- Hair Color?

Color is arguably the most useful of all descriptors. Hair color, for all that it is not generally an important characterizing detail, is a useful visual detail. But it’s also a very small detail that should be mentioned a briefly as possible and in a way that does not jar the narrative out of its POV (see below).

Let me ask you this: Do you remember the eye color of your most recent checker at the grocery store? Me neither. In most instances, eye color is not an important visual detail. It is, however, an intimate detail. We start noticing someone’s eye color when we really start paying attention to them, seeing them as an individual rather than just another person. The eyes are the windows to the soul, which means eye color only becomes important when it aids in providing that window.

Readers rarely need to know your protagonist is 5’11.5″ inches, 170 lbs. They do, however, need have a sense of the person’s build. Tall, muscular, short, plump, attractive, average, whatever. The smallest of physical descriptors can help readers imagine the right silhouette for your character.

The Lie That Tells a Truth by John Dufresne (affiliate link)

Sometimes clothes make the man, sometimes not. Early on in the story and in certain important scenes later on, a specific description of your characters’ clothing may be important to flesh out your world and set the stage. Otherwise, follow the rule John Dufresne offered succinctly in The Lie That Tells a Truth :

[D]ress is only important in a story when it is important to the character.

And by “important,” he doesn’t mean “the character’s favorite pair of Chucks ever,” but rather “plot-advancing.”

- Scars/Special Features?

Do they matter to the story (e.g., the character has a bionic arm that let’s her defeat bad guys)? Do they define the character (e.g., the character is deeply ashamed of his disfiguring facial birthmark)? Do they establish the setting (e.g., tribal scars in a jungle setting, or green scales in an alien setting)? Then, by all means, describe them. Otherwise, what’s the point, right?

- As Seen by Other Characters?

Perhaps the trickiest part of character description is figuring out how to describe POV characters. Your protagonist, in particular, is going to be the most important person in the story and you want to provide readers the right visual image. But you also don’t want to break POV by having the character launch into a lengthy description of herself (or, just as cringe-worthy, an observation of herself in a mirror ).

The best rule of thumb is to describe only details that matter to the character and matter in the moment . However, you can also cheat just a little. When your character scratches his hand through his hair, is he really thinking about “scratching his hand through his black hair”? Nah. But he is aware that his hair is black, so you can almost always get away with sneaking that little descriptor in there. No harm, no foul—and readers have a useful detail to add to their mental image.

Setting Description

What too much setting description looks like.

The man woke up. The room he was in was big, with rows and rows of beds for other patients. It was still dark, but he knew what he would see out the window: a road, then fields, then pine trees. There were a dozen windows in this room, tall ones from floor to ceiling. The curtains were white, as were the walls and the floor. Half a dozen fans dotted the ceiling. People tossed and turned in their beds. He knew all their names: Peter in the far corner, then Jim, Bob, Andrew, then him. Beyond the room was a desk for the nurse on duty, then long hallways and still more rooms, most just like this one.

What Just Enough Setting Description Looks Like

Cold Mountain by Charles Frazier (affiliate link)

At the first gesture of morning, flies began stirring. Inman’s eyes and the long wound at his neck drew them, and the sound of their wings and the touch of their feet were soon more potent than a yardful of roosters in rousing a man to wake. So he came to yet one more day in the hospital ward. He flapped flies away with his hands and looked across the foot of his bed to an open triple-hung window. Ordinarily, he could see to the red road and the oak tree and the low brick wall. And beyond them to a sweep of fields and flat piney woods that stretched to the western horizon. The view was a long one for the flatlands, the hospital having been built on the only swell within eyeshot. But it was too early yet for a vista. The window might as well have been painted gray. (From Cold Mountain by Charles Frazier)

Should You Describe Your Setting…

- At the Beginning of the Book?

Half the trick of setting descriptions is finding the perfect place to put the details. As always, the descriptions only matter when they matter. So when do they matter? They matter when readers need to be able to envision the scene and when new details are pertinent to the events of the plot.

The former is a pretty broad umbrella, which will first come into play at the very beginning of the book. You will need to describe enough of your initial setting to orient readers within the scene and, just as important, to give them a sense of the overall story world—whether it’s Texas or Westeros.

This does not mean, however, that you need to describe every last bit of your overall setting right there at the beginning. Get readers oriented in that first scene, then start sowing additional details only as they become pertinent (for example, we have no idea what state or time Inman is in until further into the first chapter).

- At the Beginning of a Scene?

What about when you begin a new scene? You definitely do need to orient readers afresh after every scene or chapter break . But should you begin with a full-on description of the setting every time? Well, ask yourself this: is the setting the most important part of this scene?

If, yes, definitely open with it. You may even be able to go ahead and describe it in full, depending on the scope of its importance.

If not, hold back a little. Introduce the scene hook, sketch a few setting details to help readers get their boots on the ground, then slowly dole out other pertinent descriptors as they become necessary (i.e., as characters begin to interact with them).

- The Second or Third Time It’s Entered?

What about already familiar settings? Readers have already seen your teenage protagonist’s bedroom several times. Do you need to describe it afresh every time to reorient them? Nope. The only details you need for repeat scenes are the new ones. You’ve already given readers a mental image of this setting, which will remain fixed in their minds, unless and until you need to update it.

Mortal Engines by Philip Reeve (affiliate link)

What if you’ve got a huge, gorgeous, very unique setting? A mechanized city like in Philip Reeves’s Mortal Engines or an antebellum cotton plantation like in Margaret Mitchell’s Gone With the Wind ? Half the fun of reading about these places is getting to explore them. But that doesn’t mean you can get away with pages upon pages of detailed setting description. Do share all interesting and important details with readers, but do it artfully, by sowing it into the action of the plot and the development of the character, making all the details you share matter to the story, making them mean more than just words about brick and mortar.

Learning the art of avoiding too much description is ultimately the art of controlling your narrative. When you’re able to move past description as merely description and bring it into play as a technique for advancing plot, character, and theme, through the judicious choice of telling details, you will raise the entire tenor of your book.

>>Click here to read more posts in the Most Common Writing Mistakes Series.

Wordplayers, tell me your opinion! As a reader, have you ever encountered a story with too much description? How did it affect your experience of the book? Tell me in the comments!

Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in Apple Podcast or Amazon Music ).

Love Helping Writers Become Authors? You can now become a patron. (Huge thanks to those of you who are already part of my Patreon family !)

Sign Up Today

Related Posts

K.M. Weiland is the award-winning and internationally-published author of the acclaimed writing guides Outlining Your Novel , Structuring Your Novel , and Creating Character Arcs . A native of western Nebraska, she writes historical and fantasy novels and mentors authors on her award-winning website Helping Writers Become Authors.

Too much description?… Yes, I have seen it in MSS sent for editing. More to the point, is being given too much, too soon.

One book I was given to edit would break every newly introduced character’s dialogue with a full description of his life story and physical features. Often these were a quarter of a page long, losing any flow the dialogue had.

But sometimes, in some genres, description is not only necessary, but vital to the plot. I write crime mysteries, and need to hide pointers and clues in my descriptive passages. Sometimes a book is returned to me from a beta reader with comments like “Where did that come from?” or “So… Who was that bloke who shot him?” because they’ve not picked up on those little details. I’ve then had to go back into the plot to add extra descriptive details… and hope that my less observant readers will notice them, while others won’t just see ‘spoilers’. It’s a fine line that we writers need to tread.

Excellent point. The problem isn’t so much how much description is being shared as when and where it’s being shared. As long as the details are doled out in a meaningful way, everything usually works out just fine.

I got so much from this article. I always do when you post something.

I found your point of describing eyes very interesting. You noted that we only notice a person’s eye colour when we get close/intimate. That is a helpful tool when describing the progression of a relationship.

Thanks for all you do!

Honestly, I’m a sucker for eye color in stories for this very reason. Used well, it can almost *define* a character.

Then again, sometimes a person’s eyes are the first thing you notice on someone. Because of the very intimate nature of observing eye color, it could create such an impact on the protagonist that he forgets to describe anything else.

This happened to me in real life. I saw a woman with T!H!E! absolute purest green eyes I had ever seen in my life. I just stood there wondering how it was even possible for several long moments as she talked with someone, and after I left I couldn’t even tell you her hair color.

(Also, those were her true eye color. She became my study hall teacher the next year and she didn’t wear contacts.)

A scene with a description like this would be great for introducing a character of prominence or power (even if that power us exerted over only one character). Someone commanding, someone who draws people in– even someone who is a traitor, whom the protagonist thought he knew well (those powerful, alluring eyes) but later realizes he never really knew her that well (wait, what color was her hair again?)

Just a thought. 🙂

*if that power is exerted. My bad.

True enough. Some eye colors–especially blue–are striking enough to be immediately noticeable.

Great article again, thanks. I tend to suffer from the reverse problem, getting three or four characters in a room who just talk and nothing ever gets described.

Part of the problem with writing any kind of speculative fiction is that you put so much into the worldbuilding that you don’t want to see any of it wasted. I’m an extreme case here, I even have wiring diagrams for my spaceships. I have to be very careful to cut it down to just what is needed.

On thing I did find helped a lot was studying Dudley Pope’s historical novels. He is a naval historian and knows everything there is to know about sailing warships. He’s very good at only describing what is needed for the characters.

I hear you. It’s easy to rock from one extreme to the other. I find it useful to identify which side of the spectrum you naturally fall on, then deliberately overwrite in the other direction, then edit as necessary.

Every time I read advice about not using too much description, all I can think of is The Hunchback of Notre-Dame and how Hugo takes 10 pages in the middle of the book to describe Notre-Dame as it looked in the 15th century, followed by thirty pages on how Paris looked in the 15th century. But the book is so amazing that I don’t look down on him for that, and I’m in awe of the guy for doing his research so well (long before internet) that you would’ve thought he’d lived back then. Lesson learned: if you’re a good enough writer, you can break all the rules and no one will object.

Personally, I tend toward a bit too much a character description and far too little setting description. I have very poor awareness of my surroundings in real life, so when writing in a deep PoV I’m always focused more on my characters’ thoughts and forget they should be observing the setting as well.

Hah! It’s true. And Les Mis is even more of a culprit. But, hey, all the rules go out the window when you break them brilliantly. 😉

I’m definitely finding that describing too much is one of my main issues in my current WIP. My betas have been point out the major spots, which has been super helpful in making me aware of my tendencies. Hopefully now that they’ve planted the seed I’ll be able to see it on my own as well!

*pointing* out. 🙂

Writing description is all about exercising our imaginations on the page. It’s a good thing! It’s just that we have to learn the discernment and discipline to understand what will be effective from the readers’ perspective, and what will not. Betas are great for that.

Another important lesson for writing, and one you lay out very well.

(What is this notion that writers have to study physiognomy and spend ten lines describing the separate pieces of someone’s face– as pieces, not as the impression they make? Sigh.)

One rule I have is: description is about consistent style. As in, ask yourself “Is this the amount of description I could write for *every* equally-important moment for the rest of my writing life?” If a paragraph seems like you’ve gotten sucked into a moment more than usual–and more than it deserves–you know the reader will notice the inconsistency too.

But I think when a writer discovers she love description as a style, she should go with that… and learn how to focus it so it builds layered power that supports the story, without going off on tangents. Or the writer who likes using less, should– and find out how to get in the right minimums.

We all have our own tastes in writing. Those ought to guide us to how much time we’ll be spending on what, and how to make that work.

Back in the days when people believed in phrenology (that a person’s personality was revealed in his facial features and head shape), it might have made more sense to launch into detailed facial descriptions. Certainly, I think half the reason modern authors struggle with this is in an attempt to mimic classic authors, such as Dickens.

Great article. One of my favorite authors is the late Taylor Caldwell. I love how she wove description into her scenes.

My mentor taught me about setting and description this way. You want to engage the reader’s imagination. Describe just enough to trigger an image in the reader.

For example: “a huge four-post bed with red curtains dominated the musty room. She had to sidestep around it to open the French doors to the balcony, but the effort was worth it when the lilac scented breeze wafted over her.”

Your image of this might not match mine & that’s okay. I don’t have to describe the room further.

This is another good example of the careful use of color. That one little pop of red brings the whole picture to life.

It’s interesting. In the scene I’m working on, my protagonist finally notices this other character’s eye color, just as she begins to fall for him. Up until now, she’d only looked at his hair.

Katie isn’t just a writer and reacher—she’s a mind reader, too ?

More to the point though, some of those “descriptions done right” are actually quite lengthy. The reason they don’t come across as such is they’re not delivered as laundry lists (info dumps), but rather integrated into the narrative to drive it forward. That’s a pretty important distinction, in my opinion (which you do drive home throughout your article).

It’s not necessarily about length or amount. The delivery is just as important.

My rule for writing description is that whatever I describe has to be relevant to some other element of the story – the character, theme, plot, etc. Most often I look to relevance to the character. If I’m describing something about the scenery, it has to be something that is important to the character or that gives insight to who he is or his state of mind. If the character wouldn’t notice it, or it wouldn’t have any impact on them in the long run, then why describe it? But that gives you so much opportunity to play with detail, just with a purpose.

I think another rule I have is to never ‘pause the story’ so to speak to describe something. I hate when I’m reading something and it just takes a paragraph or two out at the beginning of a scene to say “and here’s what this place looks like” without doing anything to advance the story or give insight into the character(s).

Good rule. Optimally, description should be about more than just sharing a visual image. It should pull double or triple duty in also sharing subtext or characterization.

My favorite character description is Jane Austen’s of Henry Tilney: “if not quite handsome, was very near it.” Who knows if his hair was dark or fair, or if he had an aquiline or Grecian nose? I think anyone would form their own mental image from that description. Not to mention that a character’s being very nearly handsome is much more endearing than his being devastatingly so.

I get bored very quickly with descriptions of anything that is supposed to be beautiful or grand or amazing. It just isn’t interesting to me. (Poorly developed Se, maybe?) But my tastes are very opposed to the cinematic style, and that’s certainly NOT a universal preference. I think most people are different from me in this respect. I do like descriptions of building floor plans, the layouts of towns, trees, small objects, and animals. And clothing, within reason. 🙂 Which I guess goes to show, you can’t please everyone, but that’s no excuse for writing descriptions that are so overblown or so bare that they please no one.

Good point! Imperfections are often the most attractive qualities in descriptions.

I have always loved the depth and texture in the beginning of The Wind in the Willows by Kenneth Grahame. It pulls me into the delightful world of Ratty, Mole, and the others quite well. My wife, on the other hand, couldn’t get passed that into the body of the book. I normally dislike too much description because it really doesn’t matter (as you point out so well). But, in some cases, pulling the reader into the world is critical to the reader being immersed enough in the world to live in that world for the duration of the book. One example of that is the Inkheart Trilogy by Cornelia Funke. She does a masterful job with her descriptions. As always, my two cents.

Beautiful prose makes a huge difference in the amount of description readers will be willing to swallow. If it’s poetic and lovely, it has value of its own.

Another very good post, thank you.

When it comes to descriptions a good piece of advice I have come across is to describe things from the standpoint of what is likely to stand out to the character as far as their profession is concerned. A doctor will see a room differently than a carpenter and a office worker a garbage collector. So this is also something to keep in mind.

In my WIP my MC has the ability to sense the subtle energies within her environment so at times depending on what is going on this may be the first thing I focus on when she enters a new location, especially if their is animosity directed toward her which is from time to time. Even when she is meditating in one scene a little Japanese girl that has become quite fond of her is hiding and watching her and I explain the girls emotions through how Manitra perceives them in the fluctuations of those subtle energies.

Even when a character enters a scene it is good to focus on the things necessary to the plot and things that will naturally stick out to that character based on their background or their personality. Hence a very timid character is likely to see every shadow, and corner as a place where something bad could happen or perhaps even a shell shocked soldier.

Anyhow I think I have made my point and I am by now means trying to do your job and teach anyone anything, just sharing from the heart and hope something helps someone see this wonder diamond called writing from a different facet.

Keep the stimulating discussions coming.

I agree. We need to give readers enough of an overview to understand the space in which the details are going, but from there, it’s a matter of prioritizing those details that either advance the plot or develop the characters.

I loved Jean Auel’s “Earth’s Children” series until book 5. The 2 main characters were traveling slowly due to the elements. I remember thinking several times, “If she describes the snow and ice terrain one more time, I’ll scream.

And did you scream? 😉

No. I threatened, but stopped myself at the last minute. 🙂

Here is my last 10 cents on this post.

I think that it is important in character description to also take the opportunity of using it to show personality of the character, such as focusing on body language and gestures as well as physical details. I also believe that is a good idea to give just enough detail such as the most significant aspects of a character that stand out such as maybe a facial tick, bald spot, scar or whatever that identifies with them and that the reader could identify with.

With my MC, her eyes light up in intensity the more angry or flustered that she gets, it is a part of her alien biology so it is rarely necessary for me to speak about how angry she is through out my WIP because I establish this connection from the very beginning and build upon it throughout. She is a very emotional character that tends to get worked up quite a bit.

My other point is that through specific description of body language and physical appearance you can create enough of an image for a reader to get the take away that a character is gorgeous or pretty or even use the reaction of other characters to them to drive this home. This is an example brief description of a character I describe earlier in my story but am reintroducing in a different manner. There are many eyes taking notice of her along with my MC who is uncertain if this is the same person or not.

Traes’ new dance partner was quite a sight to behold, her feet glided with ease in those ankle strap platform heels, supporting a pair of legs whose smooth contours boasted the workmanship of a master artisan.

Whether a characters eyes go sprat wide and there heart starts racing as soon as character x appears on the scene or their hand slaps across their mouth and their stomach begins to churn when Miss X comes into view it doesn’t take a lot of detail per sae to get the point across of outward appearance.

Great thoughts. Show, don’t tell.

This has been so very helpful as I revise my MG novel. I tend to info dump, so it’s a good reminder to keep things simple and pertinent to my characters and plot. Thanks, K.M.!

Nothing wrong with info-dumping in the first draft, as long as you recognize and fix it later. 😉

Good article,

In the Azurian galaxy there were eight planets that were warmed by twin suns. From the suns a goddess was born. This goddess named herself Maia, the mother of all creation. She wasn’t happy with the eight existing planets so she created one. Maia looked down on the planet she created. She was pleased and decided this planet-in addition to having twin suns-would also have twin moons. She named her new world after herself for she was alone. So the planet Avanaria was born. Maia created beautiful seas and filled them with manner of life. Then she created the mountains and islands of various sizes upon which grew all luscious vegetation: flowers, vines, and tall beautiful trees. She placed fresh water lakes, rivers and streams through out the verdant landscape. She created birds over every color had she could think of and then created animals of all shapes and sizes. Then she scattered all these living things upon the numerous islands. But the goddess felt something was missing…intelligent beings! So she created many different species of magical beings-shape shifters, fairies, elves, dwarfs and different lesser deities. Her favorite were the mer-people. She was so pleased with them that she made them immortals and also made them gods to help her govern the rest of the planet. Now some of the other beings were also immortal, but they lacked control, and some of abilities. The merfolk had possessed. Maia became somewhat jealous, which led to this sage. Enjoy the adventure!

The island Elda Lamore was large, it had mountains, rivers and lakes. There was an abundance of trees, floral and fauna which creates flourishing homes for varied wildlife and the people whom reside there. There are six smaller islands the encircle Elda Lamore and they to are lush vibrant habitats for many. The palace was nestled in the foot hills Elda’s mountains. The palace grounds cover about 2,000 acres at least it has lush forests around two sides of it. There are farm lands where peasents grow produce both for the royal family and servents but also enough to feed everyone on the island. Nearer to the palace was the enchanted gardens that was well groomed and was truly a place of beauty and serenity inside the gardens are pools for beautiful fish and aviaries of exoctic birds whos colorful rivals those of the multitudes of flowers that create places for delicate butterlies and honey bees that create the most delicious honey on the planet. All around are well manicured lawns and sculpted bushes. The sweet scent from flowering fruit trees sooths and yet invigorates at the same time. Near the palace was a large dolphin fountain where beautiful koi and other colorful fish swim for the delight of visitors. Peackocks and other large colorful birds stroll around the grounds. Off to the left of the palace was a series of cottages and huts. These are for guests. Healers and servents one especially large building was the infirmary to house the ill and injured. Near the cottages are three salt water pools one is very large there was also two in the palaces private court yard for the royal family. Each cottage and hut also have private pools in their baths. The infirmary has four pools for those too ill to leave the building. It is important merfolk to be able to emerse in salt water every 7 hours that they reside on land. Merfolk can live on land as long as they can have salt water pools or the sea nearby. When they change back to their natural state they get fish tails where their hops and legs would be and gills behind their ears with the gills they can breathe both air when out of water and breathe under the water just like the fish they share the seas with. Away from the rest of the palace buildings are stables for horses and livestock . Next to this was the armory where weapons were stored and the guards and warriors resided. Next to this was the training grounds here men and women trained in the arts of weaponery, and stealth and defense and hand to hand combat although it has rarely been needed until now….

Is this too much description? What do you think?

The first paragraph sounds like a world fable–such as Indian creation myth. If that’s your intent, then “telling” style works well enough. However, in all honesty, I totally start to glaze out over the second paragraph. As a reader, I need a reason to care about the details being shared.

I plan on revising both. What would you suggest me do with the paragraphs?

Particularly, since these are opening paragraphs, I would cut them entirely and open with action. Then only share the details *as* they become necessary for readers to understand what’s happening.

Okay, thank you,

In the beautiful turquoise waters of the serene sea, swam two lone mermaids. It was a very warm sunny day and the water glimmered mini rainbows when the tails of the mermaids hit the water. The mermaids were on a journey, but had stopped for refreshment and a little rest before continuing on. The older of the two was Cara, she was a priestess of great abilities and the younger mermaid was Leilani Pearl…she was a mermaid princess. Both women were enjoying the warmth of the sun when Leilani noticed a figure swimming towards them. Cara, immediately rushed to Leilani’s side to protect the mer-princess if need be. As the figure grew closer, they could see it was a merman and a very handsome one at that. Leilani looked at this stranger swimming towards them. He was gorgeous with raven hair, bronzed skin that covered a very masculine body with strong muscular arms. His mertail was teal and amethyst scaled and very strong as it propelled him to the ladies. “Halt!!” commanded the priestess holding her hand up. “State your business!” Leilani watched intently to the man’s reaction. Her eyes were a deep at the moment as they changed with her moods. The man stopped and said. “My name is Zane Merrick,” he continued, “I wish you no harm,” The mysterious stranger smiled. Leilani noticed he had very white straight teeth. He noticed her staring and smiled at her, causing her to blush. She quickly turned to Cara and raised her lovely eyebrow in question. Cara who was telepathic searched the man’s thoughts. Zane feeling the probing relaxed and didn’t say a word as he knew she was seeing if he meant to harm them. At last he was trustworthy and intended no harm she spoke. “My name is Cara, I am priestess to our Goddess Leilani,” she said as she bowed to Leilani. Zane bowed to the young mer-princess and said. “it is an honor to meet you my lady,” then he bowed less deeply to Cara. “and you also my priestess,” The women were impressed by his good manners…Cara telepathically told Leilani they were safe for the moment. Zane noticed a shared look between the women and knew he passed some sort of test. He noticed the mer-princess watching him, Zane flashed her a dazzling smile and was pleased to see her blush. Leilani couldn’t believe she was blushing at a stranger! But then his eyes twinkled and he was no ordinary man and she was already smitten with him. Zane turned to Cara and asked them where the ladies were traveling. Cara looked at Leilani who nodded, “we are traveling to Elda Lamore Island, do you know of it?” Zane smiled, his brilliant blue eyes were sparkling. “In fact that is my destination as well, might I travel with you, my lady?” He asked turning to Leilani with the question part. “Yes,” she replied. “if you can keep up, we’d enjoy the company,” Then before Zain responded she turned and with a quick thrust of her tail she shot toward in the warm seas leaving Cara and Zane to follow. Zane chuckled as he admired Leilani’s beauty. Her hair was unbound and flowing behind her. It was shiny and raven like his with turquoise steaks. Her skin was gold and her tail was turquoise and amethyst. He noticed a birth mark on her left shoulder of a crescent moon in fish scales. Around her slender throat she wore exquisite pearls. He loved her fire and knew he was already smitten by her. This will be an interesting trip, he thought as he hurried to catch up with the women. Cara keeping close to Leilani could sense that Zane was very attracted to the young goddess, and likewise she was with him. I’ll have to keep an eye on both of them. She thought, but secretly she smiled. They would be a good pair she thought. Cara had been given as a hand maiden to Leilani when the goddess was born. As time went on Cara discovered she was a priestess and a powerful one, so she was sent to study with other priestess so she could learn how to use her many gifts. She could have left goddess then and become powerful in her own right. However she loved the young goddess and felt her place was with Leilani. Cara was also a beautiful woman, She had dark hair and slender build. Her tail was a lovely teal color. After what was quite a long journey the traveling trio finally reached the island. Although it was late, there was plenty of daylight left due to the planet having two suns. The merwomen hesitated while Zane swam to the beach, and then he quickly hauled himself ashore. Leilani couldn’t help but admire the strong bronzed back as he flipped his mertail on the beach then in an instant his tail split and morphed into two very muscular bronzed legs. Then with a clap of his hands, he magically addressed his nakedness, and leggings, a tunic, and leather boots covered his excellent body. Smiling, he reached out to help the ladies ashore. Leilani motioned for Cara to go first. She was suddenly feeling a little shy for some reason and it frustrated her. Cara smiled and allowed Zane to help her on shore, where she too quickly changed her mertail for legs then covered her body with a soft ankle length flowing lavender gown and sandals. Zane then offered his hand to Leilani. “My lady?” he smiled, but his eyes were intense. Leilani’s heart skipped a beat! She shook her head, “I can do it myself, thank you!” she spat out a bit sharply. Zane looked surprised, but bowed and said. “as you wish my lady,” and backed away. Cara’s eyes widened with disapproval at Leilani’s words and actions. Leilani blushed with shame, she didn’t know why she said and acted like that. She pulled herself on the beach. Zane turned his back while she quickly touched the pearls around her throat, instantly her tail morphed into two lovely golden brown legs. Another pearl she was clothed in an ankle length turquoise flowing gown similar to Cara’s. She was holding a pair of sandals to keep them dry. “You may turn around now,” Leilani said. Zain sucked in his breath, his eyes widening as he saw Leilani’s true beauty. He admired her raven locks that hung past her waist and covered her full breasts. Her figure was tall and slim, but with the right amount of curves he thought with a smile. Cara seeing the fire between the two of them and chuckled, in her heart she knew they would make a good match. Leilani took a step and cried out in pain as her bare foot stepped on a sea urchin practically hidden in the sand. Zane immediately swooped her up into his strong arms much to her embarrassment. “I’m okay,” She gasped as pain shot up her leg. Cara quickly got out her medicine bag. She found a potion and talking a gauzy strip of cloth soaked it with the potion then she gently wrapped it around Leilani’s throbbing foot. Then she gave the goddess something to drink from another bottle. She will be alright she assured a very worried Zane. Urchins are poisonous but the potion will cure it. However she won’t be able to walk for a while. She explained. Zane tightened his hold on Leilani, who was quite pale at the moment. I shall carry her, he thought, and then he declared, “She is light as a feather.” He grinned at Leilani. Leilani was terribly embarrassed, yet it felt very nice in his arms, and so they stared up the path to the enchanted gardens, and so their love story begins.

Is this good or does it need to be rewritten or has to much description?

Much better!

However, please remember this is not a critique site. I’m happy to respond to specific writing questions or to comment on very short excerpts of a few sentences. But I would appreciate it if longer excerpts weren’t posted frequently. Thanks!

Okay, thank you will do.

Character descriptions: He was gorgeous with raven hair, bronzed skin that covered a very masculine body with strong muscular arms. His mertail was teal and amethyst scaled and very strong as it propelled him to the ladies. Cara was also a beautiful woman, She had dark hair and slender build. Her tail was a lovely teal color He admired her raven locks that hung past her waist and covered her full breasts. Her figure was tall and slim, but with the right amount of curves he thought with a smile. Her raven hair was unbound and flowing behind her. It was shiny and raven like his with turquoise steaks. Her skin was gold and her tail was turquoise and amethyst. He noticed a birth mark on her left shoulder of a crescent moon in fish scales. Around her slender throat she wore exquisite pearls.

Do you want me to make these better I mean the descriptions?

Again, I’m sorry, but I’m not able to critique large excerpts.

What I would encourage you to do is closely examine the examples in this post, both the good and bad, and identify what it is you think works and doesn’t work about them. Then try to apply that to your own descriptions.

Okay, thank you. When you write the setting do you write long sentences or short sentences or weather?

Example: It was a warm day in the enchanted gardens on Planet Avanaria.

Leilani, the goddess of the serene waters was in the library looking at books in which it had a writing desk and book shelves filled with books.

A mix. You want to vary the rhythm of your prose. I would also try to stay away from phrases that start “it was a…”, as these are almost always telling. Instead, show readers what the day is like, e.g., “Warm sunlight filtered through the palm leaves…”

Okay, thank you. Where Leilani leaves there are twin suns and twin moons on Planet Avanaria.

Is your Dreamlander book have a galaxy or is it on earth?

Okay, thank you. Where Leilani leaves there are twin suns and twin moons on Planet Avanaria so it has about ten planets in the azurian systom.

Part of it is on Earth, part of it takes place on a parallel world.

“Do they matter to the story (e.g., the character has a bionic arm that let’s her defeat bad guys)?”

As a matter of fact, my superhero protag has exactly that. I haven’t ever taken time to describe it though, you just get to know it as you get to know her better through the story– that it’s charcoal grey, that it creates a bit of imbalance in her appearance (slightly thicker than her other arm), etc. That’s because I’ve been doing a slow reveal of a secret behind its origin that even the protag isn’t aware of.

Good post and very true. I’ve seen stories wherein the description of clothing was so extensive I thought I was reading a fashion magazine rather than a novel.

But it can be difficult to balance how much the reader needs to know with keeping the story moving. A friend wrote and self-published a book and had me proof it first, and that was one of the things I had to point out to her. She was giving too much information right at the start (information dump of sorts) trying to get the reader up to speed. But the effect was too overwhelming and was more apt to bore the reader so they didn’t continue. She was able to pare it back and omit some of it or shift it to elsewhere in the story where it fit a little more seamlessly and didn’t prove so distracting.

It definitely is a balance–and it’s definitely subjective. For example, fantasy novels often require far more description (including that of clothes) than do contemporary novels, simply because readers need more help in envisioning a strange world. But we still have to be careful not to go overboard, lest we bore them.

The moment our descriptions become a list, similar to bullet points, it loses much impact. When we resort more to telling than showing. The “goldilocks” solution? Not too much, not too little? Or, as you stated, “…hey, all the rules go out the window when you break them brilliantly…” Until then, incorporate all the senses—use color, and then, only enough. Is the phrase, with restraint? Thanks, Katie!

Definitely. As is evident in the examples I used in the post, good description isn’t necessarily *shorter* than bad description, and this is because it’s artfully posed, rather than simply a grocery list of items and details.

It’s what I said! ?

Very important and timely post, K.M. Early on I decided to be less descriptive of characters in my romance stories. I thought that I would let my readers imagine how they looked. Who was I to decide how you envisioned your perfect man or woman. Brhmp! Wrong answer. So then I started describing everything down to the color of a grasshopper’s eyes. My readers would comment, “You’re very descriptive, aren’t you?”Brhmp. Wrong answer again. So now I’ve worked at using the descriptions more naturally to layer and accentuate the story. So now less Brhmps. But I need your advice on a story I’m writing which is set in Paris. I don’t want to describe the typical landmarks, ex. Eiffel Tower, Arc de Triompe, Shakespeare and Company Bookstore, etc. The couple, Quille and Graham enjoying an intimate villa on New Year’s Eve. I’ve never been to Paris, but I can research the look of the French countryside and the floor plan, furniture, and rooms of a villa. I want to really concentrate more on describing the French cuisine since Graham is in culinary school in the States. What do you think Brhmp or thumbs up? Thank you for the post.

It’s all about offering a few well-placed evocative details. Sensory details *other* than sight (since they’re comparatively underused) are especially excellent. Play with the rhythm of the prose too. You can get away with more description if the presentation is utterly delicious.

Great advice. It’ll be a wonderful writing challenge for me. Thank you so much for taking the time. Just know I do appreciate you.

My pleasure! 🙂

Great post, thank you! I am always mindful of not overdoing descriptions, especially with characters. From a young age I’ve loved reading and developing “my version” of how a favourite character would appear. Hated it if a movie version was released and they chose the “wrong” actors for the part. LOL.

Now that I have started writing, I try to mould my characters by showing their personality, stance, actions and words more than their appearance. Once I feel satisfied that my MC’s have successfully been portrayed as worthy of a reader’s total attention will I begin to fill in little titbits of specific information about physical or facial appearance. With minor characters, I don’t get very specific at all. I just want the reader to know that they are naughty or nice, helpful or harmful etc. Their words or deeds will generally say all that is necessary for the reader to know about them.

Your posts teach me so much and constantly inspire me to keep going with my writing K.M. I’ve left it late in life to start actually writing a novel. I have journals with dozens of ideas and premises for different stories from a lifetime of dreaming that one day…! Trouble is, I may have to live to the age of one hundred and twenty to achieve them all.

I’m big on wanting to make sure I’m envisioning characters in line with how the author intended, so one of my pet peeves along these lines is when the author fails to describe the character well enough early on, only to stick in details later than completely mess with my own perception. :p

Agreed to all of the above. Though one of the critiques I got from a mentor was it was okay to put a *little* more descriptive detail than I had been since I was writing fantasy. I’d been erring on the side of sparsity.

One of my pet peeves, though, is when a character description is given late and I’ve already established something else in my mind. I don’t expect a detailed description right off the bat but I expect hair color, gender & an idea of their age within the first few pages. 3 chapters later and I’m going to be very annoyed to discover the 16-year-old brunette I’ve been picturing is a 27-year-old blonde.

I got dinged in the rough drafts of my first fantasy for too little description too. There’s a reason fantasy books tend to be almost twice the size of most other genres. 😉

I felt the need to describe hair length and clothing in my first book because I thought it was important. My protagonists were all metalheads who fully embraced the heavy metal lifestyle as did most of their compatriots. The antagonists had shorter hair and always dressed more conformist. Now that I write this, I realize that I didn’t have to use these descriptions in every encounter, which I seemed to do.

It’s funny how we, as authors, aren’t always aware of the overall effect we’re creating. This is why it’s so great to let a little time pass to give us perspective.

This is tricky for me. I don’t write “too much” description when I’m using contemporary settings — so little has to be explained. For a write-for-hire book the editors loved the descriptions I used for the “upper class” vampires (they didn’t sparkle. It was before Twilight so …). I didn’t go into too much detail, because I could use shorthand, e.g., a scene where two teenage boys are describing one of the unbeknownst-to-them vampire girls:

“She’s classy; you can tell because she gets her corsets from La Perla instead of Hot Topic.”

“What’s La Perla?”

“The Ferrari of lingerie.”

The reader can fill in the blanks from there. But in my own fantasy set in a Roman analogue world I went into a lot of description, which made my beta readers’ eyes glaze over. I lacked confidence they would “get” that the setting, as you said. I was also hampered because the words for everyday objects aren’t words we use now: we don’t describe dresses as a peplos or a chiton. Because the story is not on “Earth” I didn’t have the option of just saying “Grecian-style dresses,” especially as I don’t call the “Greeks” by that name. Streamlining was definitely a challenge.

What I am absolutely determined to do is to avoid deadening my readers’ souls with “Gormenghast” levels of description. The scene that still haunts me, years after I abandoned that book, is a scene where a servant is walking through a room on his way to some other place. I think it said he took a step — and then pages of descriptions follow, of the room and everything in it. Then he takes another step, and to my horror, he was still in the room! He hadn’t gotten out of it yet and I couldn’t bear to see what descriptions would follow that next step.

Hah! But at least you know your good taste is growing as you’re able to recognize the flaws in past books.

Jamie… your comment about ‘words no longer being used’ implies that you think readers won’t understand… or won’t be able to work it out.

Aren’t you being a little elitist? Aren’t you implying that your readers aren’t intelligent enough to pick up on words that are new to them, and get the gist (these days, they can always google them). Why dumb everything down to the level of comic books, lowest common denominator TV, Hollywood, and gaming?

If I’m writing a scene, with a character who is an expert in something, I’m not going to use words that he wouldn’t use to describe what he’s doing, just because those are the words Mrs. Housewife in the street might use.It wouldn’t feel real (e.g. she might call a locomotive a ‘train’, but to a train man, it’s only a train when it’s got wagons or carriages attached.).

An intelligent (though not necessarily informed) reader will accept the ‘new’ words because it all feels real to him or her.

As writers, we should not only entertain, but enrich our readers. Their vocabulary is a good place to start.

I’m sure I’ll make my share of mistakes in this one! I’m more worried about not giving enough description because my sentences tend to be more simplistic. Feedback from Beta-readers is probably the best thing to help I would think.

Reading wise I’ve seen the different ways authors utilize their descriptions. Some convey it very differently. I guess this would be their voice or style?

The literary types who intentionally over-utilize descriptions drive me nuts. George R.R. Martin is a wonderful author, but he does tend to get too wordy. Brad Thor has a particular use of heavy descriptions for characters but it’s borderline. Most of the authors I’ve read do a pretty good job though. Now it’s my turn to learn!

Thanks Katie

Honestly, learning the right balance of description is half the battle of learning to find your voice.

I used to have the attitude that “Shakespeare never used description, why should I?”

Of course, I know I’m not Shakespeare. I simply use him as proof that description is not necessary. Furthermore, it’s obvious that there are plenty of great stories with description. So I have tried (and will continue to try) to discern the purpose of it, and maybe even incorporate it into my stories.

And, of course, he was writing plays. 😉

Touche. Story alone is a mad hydra of forms within that of writing. I withdraw that point for further revision. Regardless, I still feel the need to analyze what I read and decide what makes it good, which I’m sure you will most certainly agree.

Totally agree! 🙂

I definitely have a hard time drawing the line between too much description and too little, although I tend to not describe enough. Thanks for the great article!

You’re not alone. All of writing is about finding the right balance. 🙂

Hi! I’m midst of a creative block due to “rules I have to follow”. I know this sounds weird, but I wrote a book without knowing any writing technique. But I’ve learned a lot with your blog (and others similar with helpful content) and I decided to rewrite it. I don’t know if you read and respond to recent comments in old posts, but I’ll shout for help anyway: First question: I have some minor characters that appear very very quick in the beginning, but they contribute a lot to history, and they gain greater prominence later. Should I describe them physically (without exaggeration of course) as soon as they are introduced, or may I do this later? Second question: I had read another post of yours about word count (I’m going crazy with it!!!), but I have an average of 1500 words/chapter. When it happens that a chapter has less than 1000 (I’ve read somewhere that this is not good), is everything okay or should I mend it to another by giving a line break etween the chapters? Thanks.

If the characters are important, I would probably go ahead and ground them in the readers’ minds with some solid physical descriptors–pacing of the story allowing, of course.

As for chapter length: it’s ideal if all the chapters are around the same length. But it’s not a dealbreaker if you have one that’s shorter or longer. Again, it depends on pacing. Sometimes it works to stitch it into a previous chapter, sometimes not.

Thank you! 🙂

I listen to your podcast RELIGIOUSLY. I typed in “I write too much description in my novel,” and this is the first article to appear. I think it’s kismet. Such a pleasure using your advice and always digging deeper into my decisions for my narrative.

it’s so weird before I would go to great pains to write just the right descriptions for chapters as they were made (reallll slow) now I find I do the dialogue first and fill in the rest later. My first chapter looks and reads different from how I do it now. I kind of want to (oh the horror) edit it again but don’t know if I should touch it at this time. Character growth? voice changing? Trying too hard last time? Ugg.

I’ve had an entire Sci-fy/fantasy saga in my head for more than ten years now. Finally, I have the chance to write it but I’m struggling with too much description. (I’m a verbose extravert in real life, so now I’m paying for it! XD) Thank you so much for this. It really helped. I needed a little guidance.

Generally, I never remark on sites however your article is convincing to the point that I never stop myself to say something regarding it. Please take time to visit my blog on Things to Avoid in Writing Romantic Suspense Novel Hope this will help.

Regards Monique

Just picked up Hogan’s alternate history book The Proteus Operation. First two paras are a bunch of blather about the color of the ocean and little seagulls following the ship (first para describing and then second para explicitly linking the sullen colors to the character’s mood). Totally bored me and reminded me of why I couldn’t get into that book 40 years ago.

And I say this as a served naval officer who can really truly chatter about the cool things you see on a submarine coming into port (dolphins and flying fish and fresh air and the like). But who the fuck cares about all that stuff when it’s so ancillary to the plot (which is not about oceanography, but about alternate history time travelers inventing the a bomb and such). If he had just told me the nuclear sub Narwhal was coming into port and the skipper was irked because he was carrying four spooks who he didn’t know what they were doing…that would be a hook! Not the damned two paras of filler.

Books are too damn long anyhows…then you put in filler? And all the fancy words for colors and adjectives and such don’t impress me. Give me nouns and verbs. And it’s not because I’m too dumb to get the complex crap. I’m too smart to think that’s good writing.

[…] is a multitude of examples that go into detail on how to trim down your prose. This one I found particularly informative when I was researching for this […]

[…] of description. In the article “Most Common Writing Mistakes, Pt. 58: Too Much Description” ( https://www.helpingwritersbecomeauthors.com/common-writing-mistakes-much-description/ ) K.M. Weiland discusses how getting description wrong can ruin a story. She states that there are […]

[…] much is too much description? [K.M. Wheiland has a thought on that.] I know that I usually lack in the description area and that my descriptions […]

[…] https://www.helpingwritersbecomeauthors.com/common-writing-mistakes-much-description/ […]

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

- Novel Outlining

- Storytelling Lessons From Marvel

As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.

Write Your Best Book

Check out my latest novel!

( affiliate link )

Free E-Book

Subscribe to Blog Updates

Subscribe to blog posts rss, sign up for k.m. weiland’s e-letter and get a free e-book, love helping writers become authors.

Return to top of page

Copyright © 2016 · Helping Writers Become Authors · Built by Varick Design

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

37 Description

This morning, as I was brewing my coffee before rushing to work, I found myself hurrying up the stairs back to the bedroom, a sense of urgency in my step. I opened the door and froze—what was I doing? Did I need something from up here? I stood in confusion, trying to retrace the mental processes that had led me here, but it was all muddy.

It’s quite likely that you’ve experienced a similarly befuddling situation. This phenomenon can loosely be referred to as automatization: because we are so constantly surrounded by stimuli, our brains often go on autopilot. (We often miss even the most explicit stimuli if we are distracted, as demonstrated by the Invisible Gorilla study )

Automatization is an incredibly useful skill—we don’t have the time or capacity to take in everything at once, let alone think our own thoughts simultaneously—but it’s also troublesome. In the same way that we might run through a morning ritual absent-mindedly, like I did above, we have also been programmed to overlook tiny but striking details: the slight gradation in color of cement on the bus stop curb; the hum of the air conditioner or fluorescent lights; the weight and texture of a pen in the crook of the hand. These details, though, make experiences, people, and places unique. By focusing on the particular, we can interrupt automatization. We can become radical noticers by practicing good description. [1]

In a great variety of rhetorical situations, description is an essential rhetorical mode. Our minds latch onto detail and specificity, so effective description can help us experience a story, understand an analysis, and develop more nuance within a critical argument. Each of these situations requires different kinds and levels of description.

First Year Writing courses often dedicate at least some space to practicing description because 1) it’s employed in nearly all academic genres and disciplines, and 2) it requires a level of specificity and an attunement to detail that’s foundational to many other writing situations. It’s rare that a student will be penalized for being too specific. The opposite is usually the case. As Ken Macrorie explains in “The Poisoned Fish,” by the time students reach college they’ve often learned to race through writing assignments by deploying an academic jargon he calls “engfish,” a strange dialect that sounds fancy but doesn’t say much at all, precisely because it’s so general, abstract, or aloof from reality. An early emphasis on rich description can serve as writing salve.

Objective vs. Subjective Description

One of the traditional ways of thinking about the rhetorical nature of description is to distinguish between “objective” and “subjective” descriptions. In early 20th-century textbooks, such as F.V.N. Painter’s Elementary Guide to Literary Criticism , we get the following definitions:

Objective: “Objective description portrays objects as they exist in the external world. It points out in succession their distinguishing features.”

Subjective: “Subjective description notes the effects produced by an external object or scene on the mind and heart. The eye of the writer is turned inward rather than outward; he brings before us the thoughts, feelings, fancies that are started within his soul.” [2]

Although a bit crude, this distinction has stuck around. We can still find this framework in contemporary textbooks such as Mark Connelly’s Get Writing: Sentences and Paragraphs . Connelly provides the following example:

Objective: “The LTD 700 is a full-size sedan that seats six adults and gets 17 mpg. The base price is $65,000 and includes a GPS system, overhead DVD player, and power seats.

Subjective: “The LTD 700 is a gaudy, boxy throwback to the gas-guzzlers of the 1970s. It is grossly overpriced and laden with the high-tech toys spoiled consumers love to flaunt in front of their loser friends.” [3]

Both examples include basic details that classify them as “descriptive discourse,” but the second one contains more emotional language that more obviously reflects the judgments and values of the speaker.

Why would a writer choose to write more objectively or subjectively?

As with other rhetorical modes, what description looks like depends on the genre and purpose. It’s highly situational. We expect to find more objective-sounding descriptions in medical and law enforcement texts. A subjective description would look out of place in a medical textbook. But in personal stories, memoirs, and other more creative writing situations, objective descriptions would seem odd. Academic writer’s must carefully consider the purpose of their writing, as well as the conventions associated with the genre: is the assignment asking them to explore and communicate their subjective response to certain objects and experiences, or is it asking for a rigorously antiseptic account of the facts?

The first technique below will help you begin practicing specificity , which is important for all forms of descriptive writing. The subsequent techniques will help students practice more complex and subjective forms of description, including “thick description,” experiential language, and constraint-based scene descriptions.

Building Specificity

Activity courtesy of Mackenzie Myers

Good description lives and dies in particularities. It takes deliberate effort to refine our general ideas and memories into more focused, specific language that the reader can identify with.

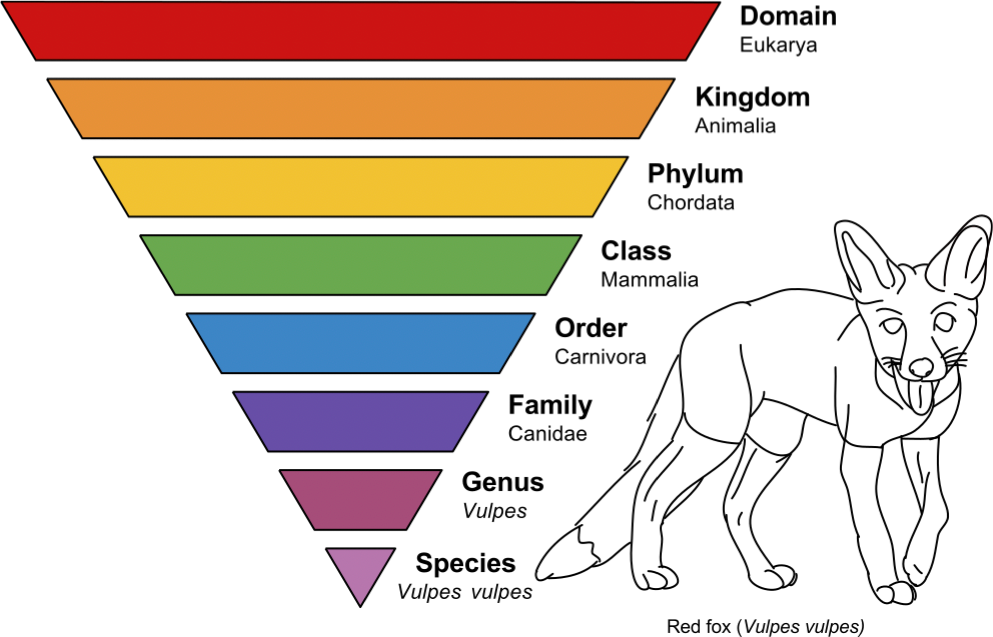

A taxonomy is a system of classification that arranges a variety of items into an order that makes sense to someone. You might remember from your biology class the ranking taxonomy based on Carl Linnaeus’ classifications, pictured here.

To practice shifting from general to specific, fill in the blanks in the taxonomy below. After you have filled in the blanks, use the bottom three rows to make your own. As you work, notice how attention to detail, even on the scale of an individual word, builds a more tangible image.

| (example): | animal | mammal | dog | Great Dane |

| 1 | organism | conifer | Douglas fir | |

| airplane | Boeing 757 | |||

| 2 | novel | |||

| clothing | blue jeans | |||

| 3 | medical condition | respiratory infection | the common cold | |

| school | college | |||

| 4 | artist | pop singer | ||

| structure | building | The White House | ||

| 5 | coffee | Starbucks coffee | ||

| scientist | Sir Isaac Newton | |||

| 6 | ||||

Compare your answers with a classmate. What similarities do you share with other students? What differences? Why do you think this is the case? How can you apply this thinking to your own writing?

Thick Description

Thick description as a concept finds its roots in anthropology, where ethnographers seek to portray deeper context of a studied culture than simply surface appearance. In the world of writing, thick description means careful and detailed portrayal of context, emotions, and actions. It relies on specificity and rich milieu to engage the reader.

Consider the difference between these two descriptions:

| The market is busy. There is a lot of different produce. It is colorful. | vs. | Customers blur between stalls of bright green bok choy, gnarled carrots, and fiery Thai peppers. Stopping only to inspect the occasional citrus, everyone is busy, focused, industrious. |

Notice that, even though the description on the right is obviously longer, the word choice is more specific. The author names particular kinds of produce, along with specific adjectives, which sharpens the image. Further, though, the words themselves do heavy lifting—the nouns and verbs are descriptive too! “Customers blur” both implies a market (where we would expect to find “customers”) and also illustrates how busy the market is (“blur” implies speed), rather than just naming it as such.

Finally, rather than just referring to the “market” and “produce,” the second description interweaves customers, market architecture, and different kinds of produce. It’s buzzing with activity and different actants . As Norman K. Denzin explains, thick description “presents detail, context, emotion, and the webs of social relationships that join persons to one another.” [4] It is, in other words, highly contextual.

Effective thick description is rarely written the first time around; it is re- written. As you revise, consider that every word should be on purpose.

“Thick Description” Workshop

To practice a form of thick description, follow these steps:

- Choose an object you’re familiar with, and begin by listing as many objective details as possible. Practice specificity using the taxonomic method.

- Next, rewrite the description from Step 1, but now include details related to place and time . Give a setting.

- Finally, rewrite the description from Step 2, but show how individual actors (such as yourself) interact with the object.

Micro-Ethnography Workshop

An ethnography is a form of writing that uses thick description to explore a place and its associated culture. By attempting this method on a small scale, you can practice specific, focused description.

Find a place in which you can observe the people and setting without actively involving yourself. (Interesting spaces and cultures students have used before, include a poetry slam, a local bar, a dog park, and a nursing home.) You can choose a place you’ve been before or a place you’ve never been. The point here is to look at a space and a group of people more critically for the sake of detail, whether or not you already know that context.

As an ethnographer, your goal is to take in details without influencing those details. In order to stay focused, go to this place alone and refrain from using your phone or doing anything besides note-taking. Keep your attention on the people and the place.

Spend a few minutes taking notes on your general impressions of the place at this time.

- Use imagery and thick description to describe the place itself.

- What sorts of interactions do you observe? What sort of tone, affect, and language is used?

- How would you describe the overall atmosphere?

Spend a few minutes “zooming in” to identify artifacts—specific physical objects being used by the people you see.

- Use imagery and thick description to describe the specific artifacts.

- How do these parts contribute to/differentiate from/relate to the whole of the scene?

After observing, write one to two paragraphs synthesizing your observations to describe the space and culture. What do the details represent or reveal about the place and people?

Imagery and Vivid Description

Strong description helps a reader experience what you’ve experienced, whether it was an event, an interaction, or simply a place. Even though you could never capture it perfectly, you should try to approximate sensations, feelings, and details as closely as you can. Your most vivid description will be that which gives your reader a way to imagine being themselves as of your story.

Imagery is a device that you have likely encountered in your studies before: it refers to language used to “paint a scene” for the reader, directing their attention to striking details.

Here are three examples:

Bamboo walls, dwarf banana trees, silk lanterns, and a hand-size jade Buddha on a wooden table decorate the restaurant. For a moment, I imagined I was on vacation. The bright orange lantern over my table was the blazing hot sun and the cool air currents coming from the ceiling fan caused the leaves of the banana trees to brush against one another in soothing crackling sounds. (Anonymous student author, 2017. Reproduced with permission from the student author.):

The sunny midday sky calls to us all like a guilty pleasure while the warning winds of winter tug our scarves warmer around our necks; the City of Roses is painted the color of red dusk, and the setting sun casts her longing rays over the Eastern shoulders of Mt. Hood, drawing the curtains on another crimson-grey day. (Anonymous student author, 2017. Reproduced with permission from the student author.)

Flipping the switch, the lights flicker—not menacingly, but rather in a homey, imperfect manner. Hundreds of seats are sprawled out in front of a black, worn down stage. Each seat has its own unique creak, creating a symphony of groans whenever an audience takes their seats. The walls are adorned with a brown mustard yellow, and the black paint on the stage is fading and chipped. (Ross Reaume, Portland State University, 2014. Reproduced with permission from the student author).

You might notice, too, that the above examples appeal to many different senses. Beyond just visual detail, good imagery can be considered sensory language: words that help me see, but also words that help me taste, touch, smell, and hear the story. Go back and identify a word, phrase, or sentence that suggests one of these non-visual sensations; what about this line is so striking?

Imagery might also apply figurative language to describe more creatively. Devices like metaphor, simile, and personification, or hyperbole can enhance description by pushing beyond literal meanings.

Using imagery, you can better communicate specific sensations to put the reader in your shoes. To the best of your ability, avoid clichés (stock phrases that are easy to ignore) and focus on the particular (what makes a place, person, event, or object unique). To practice creating imagery, try the Imagery Inventory exercise and the Image Builder graphic organizer in the Activities section of this section.

Vivid Description Workshop

Visit a location you visit often—your classroom, your favorite café, the commuter train, etc. Isolate each of your senses and describe the sensations as thoroughly as possible. Take detailed notes in the organizer below or use a voice-recording app on your phone to talk through each of your sensations.

| Sight |

|

| Sound |

|

| Smell |

|

| Touch |

|

| Taste |

|

Now, write a paragraph that synthesizes three or more of your sensory details. Which details were easiest to identify? Which make for the most striking descriptive language? Which will bring the most vivid sensations to your reader’s mind?

Description Exercises for Story-Telling

This activity is a modified version of one by Daniel Hershel.

This exercise asks you to write a scene, following specific instructions, about a place of your choice. There is no such thing as a step-by-step guide to descriptive writing; instead, the detailed instructions that follow are challenges that will force you to think differently while you’re writing. The constraints of the directions may help you to discover new aspects of this topic since you are following the sentence-level prompts even as you develop your content.

- Bring your place to mind. Focus on “seeing” or “feeling” your place.

- For a title, choose an emotion or a color that represents this place to you.