An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

The Long-Term Effects of the Youth Crime Prevention Program “New Perspectives” on Delinquency and Recidivism

Sanne l a de vries, machteld hoeve, jessica j asscher, geert jan j m stams.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Sanne L. A. de Vries, Child and Adolescent Studies, Utrecht University, 3584 CS Utrecht, The Netherlands. Email: [email protected]

Issue date 2018 Sep.

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 License ( http://www.creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ ) which permits non-commercial use, reproduction and distribution of the work without further permission provided the original work is attributed as specified on the SAGE and Open Access pages ( https://us.sagepub.com/en-us/nam/open-access-at-sage ).

New Perspectives (NP) aims to prevent persistent criminal behavior. We examined the long-term effectiveness of NP and whether the effects were moderated by demographic and delinquency factors. At-risk youth aged 12 to 19 years were randomly assigned to the intervention group (NP, n = 47) or care as usual (CAU, n = 54). Official and self-report data were collected to assess recidivism. NP was not more effective in reducing delinquency levels and recidivism than CAU. Also, no moderator effects were found. The overall null effects are discussed, including further research and policy implications.

Keywords: effectiveness, randomized controlled trial (RCT), prevention, juvenile delinquency, New Perspectives, care as usual

Introduction

Although recent downward trends in juvenile offending are encouraging ( Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, 2011 ; Van der Laan & Blom, 2011 ), there is an increasing trend toward punitive responses to youth antisocial behavior ( Artello et al., 2015 ). Many studies have shown that juvenile justice programs without a therapeutic foundation (e.g., probation, deterrence, incarceration without treatment) are ineffective in reducing juvenile delinquency ( Andrews & Bonta, 2010 ; Parhar, Wormith, Derkzen, & Beauregard, 2008 ). Young adolescents with disruptive and delinquent behavior, showing multiple risk factors, need constructive change-oriented treatment ( Lipsey, 2009 ). Given that these youngsters are at risk of developing a chronic and serious criminal trajectory ( Loeber, Burke, & Pardini, 2009 ), and are highly costly to society ( Welsh et al., 2008 ), it is essential to invest in (early) preventive interventions.

The present study is one of the first outside the United States to examine the effectiveness of a prevention program targeting adolescents at risk for persistent delinquency by using a randomized controlled trial (RCT). We examined the effectiveness of New Perspectives (NP), comparing the long-term effects on self-reported and official reports of delinquency comparing adolescents who received NP or care as usual (CAU).

Previous Research on Programs Preventing Delinquency

Several (systematic) reviews have examined the effectiveness of preventive interventions. Many researchers concluded that at-risk youth (selective/indicated prevention) benefited most from these programs (e.g., Deković et al., 2011 ; Farrington, Ttofi, & Lӧsel, 2016 ; Lösel & Beelmann, 2003 ). Given that these programs are generally short and of low intensity, these findings are in accordance with the Risk principle of the RNR model ( Andrews, Bonta, & Hoge, 1990 ) in that the program intensity should be kept low for youngsters showing relative low-risk profiles.

Farrington and colleagues (2016) stated, on the basis of a systematic review, that all types of community-based interventions (including individual, family- and school-based interventions) produced an average of 5% reduction in the prevalence of problem behavior. However, although her findings on effects of early prevention programs (including monitoring and diversion) were positive, Gill (2016) , evaluating 15 systematic reviews including 13 meta-analytic studies, found that the effects of selective (secondary) prevention programs were less straightforward and depended on the program type. Programs consisting of repressive and punitive elements were ineffective, whereas programs targeting positive social relations of at-risk youth (providing informal and supportive social control) proved to be successful. Varying outcomes of selective prevention programs were also found by Mulvey, Arthur, and Reppucci (1993) , concluding that well-implemented programs, including behavioral and family-based change components, produced reductions in reoffending rates, although not in self-reported delinquent behavior. However, these results were based on a narrative review and should therefore be interpreted carefully.

Several meta-analytic studies found promising effects of family-based and behavioral-oriented prevention programs. Long-term positive effects of (behavioral) parent training in preventing antisocial and delinquent behavior were reported by meta-analytic studies of Farrington and Welsh (2003) and Piquero et al. (2009) . Furthermore, Schwalbe and colleagues (2012) indicated that family-based diversion programs resulted in a reduction of recidivism. However, the overall impact of diversion programs on recidivism was nonsignificant. Also, Wilson and Hoge (2012) found that diversion programs were significantly more successful than traditional judicial programs, but differences were no longer significant when a robust research design was used, excluding (most) alternative explanations for established intervention effects (e.g., RCT, or successfully matched control design, independency of researchers). Finally, findings of a meta-analytic study ( De Vries, Hoeve, Assink, et al., 2015 ) on the effectiveness of interventions for at-risk youth confirmed that family-based programs, including behavior-oriented techniques (training parenting skills), are most effective in preventing a persistent criminal career. Notably, group-based and highly intensive programs proved to be counterproductive.

Lösel and Beelmann (2003) found that social skills training showed positive effects in preventing antisocial behavior of adolescents, well-structured multimodal cognitive-behavioral programs showing the strongest impact on antisocial behavior. A meta-analytic study by Deković et al. (2011) examining early prevention programs found that shorter, but more intensive programs and programs targeting social and behavioral skills showed the largest effects. However, early prevention programs had no significant effects on the reduction of criminal behavior in adulthood.

In conclusion, the findings of previous studies on the effectiveness of prevention programs targeting risk factors, such as family factors and lack of social skills, show overall positive effects. However, the effectiveness of prevention programs may depend on certain conditions, such as the theoretical foundation, intensity, format, and components of the program. Moreover, several meta-analytic reviews concluded that studies with larger samples had smaller effects than those based on smaller samples (e.g., Deković et al., 2011 ; Farrington & Welsh, 2003 ; Lösel & Beelmann, 2003 ; Piquero et al., 2009 ). Andrews and Bonta (2010) found that interventions based on the RNR model principles of Risk (proportionality between program intensity and risk of reoffending), Need (targeting criminogenic needs), and Responsivity (match between program style/mode and person’s characteristics) reduced offender recidivism up to 35%. Thus, we expect that preventive interventions that are designed according to the RNR model and general principles of effectiveness derived from previous meta-analytic studies are promising in preventing a persistent criminal trajectory.

A preventive intervention, based on the theoretical framework of the RNR model ( Andrews et al., 1990 ), is NP, an intensive community-based program focusing on adolescents in early stages of delinquency. NP adheres to the risk principle by applying risk assessment and providing modules (NP Prevention and NP Plus) that differ in treatment intensity to adjust to the offender’s risk of recidivism. Second, NP aims to prevent a persistent delinquent trajectory of at-risk adolescents. To prevent persistent delinquent behavior, NP addresses the following criminogenic needs (as secondary treatment goals): poor relationships in the social network (parents and peers), cognitive distortions, and poor parenting behavior. The multisystemic approach of NP enables treatment of these multiple criminogenic factors related to delinquency and recidivism ( needs principle ).

At the start of the intervention phase, social workers systematically assess the client’s criminogenic needs to target them in treatment. Third, NP is based on the responsivity principle by adjusting treatment to the client’s motivation level and personal background. Techniques of motivational interviewing and individual coaching are used to influence treatment motivation of adolescents. In addition, the NP program is carried out in a multimodal format by incorporating a variety of effective cognitive social learning strategies (including problem-solving skills and cognitive restructuring methods; Elling & Melissen, 2007 ). NP attempts to modify cognitive distortions by using cognitive restructuring techniques based on Ellis’s (1962) Antecedent–Belief–Consequence (ABC) model of emotional disturbances. The ABC model aims to give clients insight into their irrational beliefs, or cognitive distortions, and their dysfunctional behavioral consequences ( Ellis & Dryden, 1997 ). To conclude, given that the NP program is based on the RNR model, including behaviorally oriented techniques, and a multimodal format, NP is considered to be a promising intervention preventing persistent delinquency. See for an overview of NP elements in Appendix B .

Previous evaluation studies of the NP program found reductions in delinquency ( Noorda & Veenbaas, 1997 ) and improvements in multiple life domains ( Geldorp, Groen, Hilhorst, Burmann, & Rietveld, 2004 ). These studies lacked the use of a control group, and therefore, possible confounding effects, such as maturation, could not be ruled out ( Clingempeel & Henggeler, 2002 ). To date, there is only one experimental study (De Vries, Hoeve, Wibbelink, Asscher, & Stams, 2015), showing that NP did not outperform other interventions (“CAU”) on delinquency and secondary outcomes (parenting behavior, attachment, peers, and cognitive distortions) at postintervention measurement. Previous studies, however, reported only on short-term and self-reported outcomes of the NP program. As changing behavior is a long-term and intensive process ( Prochaska & Velicer, 1997 ), it is possible that NP will result in more positive effects in the long term (minimum of 12 months after program completion), which is also known as “sleeper effects” or delayed effects of therapy ( Bell, Lyne, & Kolvin, 1989 ). Although self-report is generally perceived as a reliable and valid method of measuring criminal behavior ( Thornberry & Krohn, 2003 ), there are still limitations, such as underreporting and overreporting criminal activity. Therefore, the present study investigated the long-term effects of NP in preventing and reducing persistent criminal behavior, based on both self-reports and official records.

The Present Study

The central aim of the present study was to examine whether NP outperforms existing services (“CAU”) using a randomized control trial. First, we determined whether NP is effective in preventing and decreasing criminal (re)offending. Recidivism was assessed during 18 months after program start, 12 months after program completion, and at maximum available follow-up period per participant. We focused on percentages of reoffending, number of rearrests, seriousness (violent reoffenses), and velocity in reoffending. Next to official judicial reports, we used self-report data to reach a more comprehensive view on adolescents’ criminal behavior.

A second aim was to examine potential moderators of NP effectiveness. This approach is in line with the shift in intervention research toward a focus on the question “what works for whom?” instead of “does it work?” ( Weisz et al., 2006 ). Previous studies have indicated that boys and girls, adolescents from different ages, and diverse ethnic groups show specific risk factors related to delinquency and recidivism, and, therefore, have suggested specific interventions for these subgroups ( Hipwell & Loeber, 2006 ; Loeber et al., 1993 ; Stevens & Vollebergh, 2008 ; Van der Put et al., 2011 ). However, there is limited information about which prevention programs are effective in treating specific problems of these subgroups ( Kazdin, 1993 ; Kumpfer, Alvarado, Smith, & Bellamy, 2002 ; Zahn, Day, Mihalic, & Tichavsky, 2009 ). By examining ethnicity, age, and gender as moderators, we can determine whether the NP program is successful for all participants regardless of their specific demographic background.

Finally, a history of offending, severity of prior offending (a history of violent offenses), and age of first arrest are considered as the most important (static) risk factors of reoffending in delinquent youth ( Andrews & Bonta, 2010 ; Cottle, Lee, & Heilbrun, 2001 ; Loeber & Farrington, 1998 ). Therefore, we included these risk factors as potential moderators of program effectiveness.

Participants

Adolescents were included in the present study if they met the following criteria for NP according to the behavioral scientist: (a) age 12 to 23 years, (b) experiencing problems on multiple life domains, and (c) at risk for the development and progression of a deviant life style. Adolescents were excluded if they showed severe psychiatric problems, IQ below 70, long history of delinquency, severe drug or alcohol use (dependency), absence of residence status in the Netherlands, and absence of motivation to stop committing criminal acts.

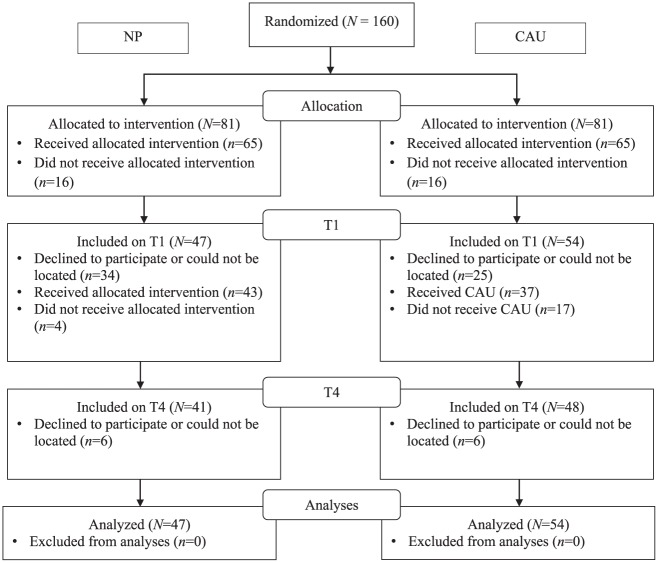

A total of N = 160 adolescents were recruited for the study at baseline ( n = 81, NP group; n = 79, CAU). Thirty-seven percent ( n = 59) of the adolescents dropped out at first assessment, because they were unwilling to participate or were untraceable, resulting in a final sample of 101 adolescents. Despite extensive efforts, 12 adolescents were lost to follow-up, resulting in an attrition rate of 7.5% of the original sample and in 89 adolescents (NP, n = 40; CAU, n = 49) who completed both pretest and follow-up (questionnaires). Details for attrition on pretest and follow-up can be found in Appendix A . As a result, full data were available on 89 participants. However, full official data were present, and therefore, the total sample consisted of N = 101 adolescents.

Little’s missing completely at random (MCAR) test indicated that data of self-reported delinquency were missing completely at random for adolescents χ 2 (4209) = 494.0, p = 1.000. Results of independent sample t tests for continuous variables and chi-square analyses for categorical variables showed no significant differences between the treatment conditions at pretest ( p > .05). We only found a trend for ethnic minority status, χ 2 (4209) = 2.7, p = .097, indicating that those with an ethnic minority status were slightly more likely to drop out at follow-up. Missing values on the categorical outcome measure, self-reported delinquency, were not estimated, as it is not well supported to impute missings in a dichotomous construct such as recidivism. Post hoc power calculations with the program G*Power ( Faul, Erdfelder, Buchner, & Lang, 2009 ) indicated that 50 participants per condition (assuming an alpha of .05, and a correlation of .50 between baseline covariates and outcome variables) were sufficient to detect a difference in problem behavior at posttest (power > .80, a small effect size defined by Cohen, 1988 , as .20). There was also sufficient power to perform moderator analyses for different subgroups (power > .80 to detect small effects for four groups).

According to the self-reports, 80% of the adolescents reported having ever committed one or more of the delinquent acts before pretest. According to official data, 47% of the adolescents had been arrested at least once before treatment. The majority of our final sample consisted of boys (67%), and the mean age at pretest was 15.58 years ( SD = 1.53). A total of 83% ( n = 84) of the juveniles belonged to an ethnic minority group (at least one of the youth’s parents was born abroad). The largest second-generation groups had a Surinamese (27%, n = 27), Moroccan (24%, n = 24), Dutch (21%, n = 21), or other background (29%, n = 29). 1 The mean age of first police contact of participants was 15.12 years ( SD = 1.46). Table 1 presents additional information on the final sample ( N = 101).

Background Characteristics and Problem Severity in NP and CAU at Baseline.

Note . NP = New Perspectives (experimental group); CAU = care as usual (control group).

Participants living in Amsterdam were recruited after being referred to NP by one of the various youth care referral agencies and (secondary) schools. The inclusion period lasted from September 2011 until April 2013. Adolescents meeting inclusion criteria for NP were randomly assigned to the experimental group (NP intervention) or control group (CAU). Self-report follow-up data of adolescents were collected 12 months after completion of the intervention. A more elaborate description of the recruitment and randomization process can be found in prior studies of De Vries, Hoeve, Assink, et al. (2014 ; De Vries, Hoeve, Wibbelink, et al., 2015).

To establish whether participants had reoffended, the official records of the Judicial Information Service (JustID) were requested in January 2015. Two starting points of the observation period for reoffending were used. The first starting point of the observation period was the date on which a person entered treatment (NP/CAU), and the second starting point was the date on which a person completed treatment. The observation period ended on the day that the official records were released by JustID (January 2015). Formal consent for using official records was obtained from the Netherlands Ministry of Security and Justice. The official records were coded using the Recidivism Coding System (RCS) of the Research and Documentation Centre (WODC; Wartna, Blom, & Tollenaar, 2011 ; Wartna, Harbachi, & Van der Laan, 2005 ).

To assess interrater agreement, 25% of the cases were randomly selected and coded by two trained junior researchers. Percentages of agreement were calculated for all variables of the coding form. The interrater reliability for categorical variables (Kappa) ranged from good (.89) for classification of violent and nonviolent offenses to perfect (1.00) for status registration (including cases as recidivism: yes or no). The interrater reliability for continuous variables was very good, with intraclass correlations ranging from .99 for date of the offense to 1.00 for the registration number of the case.

NP is a voluntary program divided in an intensive coaching phase of 3 months and a 3-month aftercare phase. Youth care workers with a caseload of four clients are available 24 hours a day, 7 days per week. During the intensive coaching phase, the youth care workers have 8 hours a week per client. The contact intensity of the program aftercare phase is low, ranging from a minimum of 4 hours to a maximum of 12 hours (in 12 weeks). NP is culturally responsive in that adolescents who receive NP are assigned to a social worker with similar ethnic background. More information regarding core components of the NP program can be found in the prior studies of De Vries, Hoeve, Assink, et al. (2014 ; De Vries, Hoeve, Wibbelink, et al., 2015).

Adolescents in the control group received various youth care interventions. The care services included probation service (20%), individual counseling (monitoring/supervision, 17%), family counseling (monitoring/supervision, 9%), individual coaching (influencing cognition and behavior, 13%), academic service coaching (tutoring and special education included, 15%), and other programs, such as social skills training, clinical group care, crisis intervention, family therapy, and Real Justice group conferencing (26%). Most services were carried out in a community-based setting (63%), in a mixed format (individual and family-based, 46%), and most services were provided by the Child Protection Board of Amsterdam (37%). Notably, 35% of the juveniles ( n = 19) did not receive an intervention (see also Appendix A for an overview of the flow of participants through the study and Appendix C for a description of treatment types offered in the CAU and NP conditions).

Demographic characteristics

Participants reported their date of birth, place of birth, and place of birth of their parents to determine their age and ethnic background. To assess the influence of age on program effectiveness, the group was divided into a group of adolescents younger than 16 years of age ( n = 54) and in a group of adolescents of 16 years and older ( n = 47). The division in age group was based on age criteria of NP, consisting of two different modalities for younger (NPP/NP Plus) and older adolescents (NP). The influence of ethnicity was assessed by dividing adolescents into two groups: native Dutch adolescents ( n = 17) and second-generation adolescents from ethnic minority groups ( n = 84). The age of first offense, total number of prior offenses (history of offending), and total number of prior violent offenses (history of violent offending) were coded from official records of JustID.

Delinquent behavior

To establish whether participants had reoffended, we used self-reports of the adolescents and requested official records from the JustID. Prevalence of reoffending was assessed by the “Self-report Delinquency Scale” (SRD) of the Research and Documentation Centre ( Van der Laan & Blom, 2006 ; Van der Laan, Blom, & Kleemans, 2009 ). Three subscales of the SRD scale were used for examination of the program effectiveness: Violent Crime (seven items), Vandalism (four items), and Property Crime (six items). In the present study, sum scores were used, indicating how often the participant showed delinquent activities in 12 and 18 months before assessment. Cronbach’s alpha for assessment of delinquent behavior was α = .74 (12 months) and α = .92 (18 months).

Prevalence, frequency, and seriousness of recidivism were assessed by official records of JustID. Recidivism was defined as the occurrence of any new conviction for any criminal offense after program start and after program completion (see also Asscher et al., 2014 ; James, Asscher, Stams, & Van der Laan, 2014 ; Wartna et al., 2011 ). Recidivism was assessed in terms of percentage (dichotomous variable: at least one arrest), frequency (continuous variable: number of any reconvictions), velocity (time until first reconviction), and seriousness of recidivism (number of violent offenses and at least one violent arrest). In addition, guidelines of the official RCS were used to code the seriousness of offenses into nonviolent (0) and violent offenses (1). Misdemeanors, such as traffic offenses, were taken into account, because the program examined in the present study is focused on prevention and on adolescents showing no or very low levels of delinquency before start of the intervention.

Analytic Strategy

First, we conducted negative binomial regression analysis to examine the main intervention effects of self-reported delinquency at follow-up (12 months after program completion and 18 months after program start), with the outcome measures at follow-up as dependent variables, treatment condition as factor, and pretest scores of the outcome variables as covariates. We applied negative binomial regression analysis instead of the more commonly used analysis of variance. The measure of our dependent variable, self-reported delinquency, is a count of the number of offenses and has a skewed and overdispersed distribution, which violates key assumptions of analysis of variance.

To take into account differences in duration of follow-up between conditions and to be able to compare assessment periods of official arrests with assessment periods of self-reports, the official judicial data were analyzed in two ways. First, we analyzed recidivism rates after start of the program (18 months) and after program completion (12 months). The two conditions were compared with regard to frequency (number) of rearrests, seriousness of reoffenses (violent reoffenses), and time to rearrest, using negative binomial regression analysis and chi-square tests.

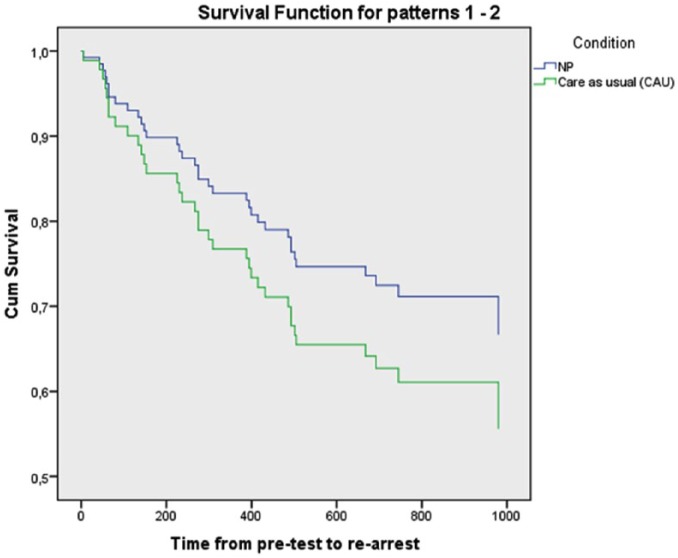

Next, we examined survival curves of the whole follow-up period (up to January 2015). The duration to follow-up was not the same for all participants due to the considerable length of the inclusion period ( M = 875.50 days, SD = 161.937). Moreover, the time to follow-up was shorter for CAU ( M = 841.41 days) than for NP ( M = 914.66 days), t (99) = 2.32, p = .023. Therefore, we controlled for differences in length of follow-up between conditions by centering the duration until follow-up period and including this in Step 1 of the survival analysis following Asscher et al. (2014) . Cox regression analyses were applied to examine differences in survival curves between NP and CAU. The centered variable of follow-up duration was added at Step 1 into the Cox regression analysis; condition (NP or CAU) was added in the second step. A chi-square difference test was used to assess whether condition would predict survival length over duration to follow-up.

Furthermore, negative binomial regression analyses were conducted for moderator analyses on the self-report delinquency data, with the moderator as factor, and including an interaction term of Condition × Moderator. Gender, ethnicity (native Dutch vs. ethnic minorities), age group (<16 vs. ≥16) were included as potential moderators. We created a risk index on the basis of history of offenses, type of offenses, and age of first arrest. Particularly those with prior violent offenses and an early onset (i.e., age of first arrest is younger than 15 years) were considered to be at high risk of recidivism, whereas the others were considered to be at lower risk of recidivism. Furthermore, we examined potential moderating effects of age of first crime, a history of offending (yes or no), and a history of violent offending (yes or no) separately.

For the moderator analyses on the recidivism data (based on official judicial reports), Cox regression analysis was conducted: Condition was entered in the first step, and the moderator and interaction between condition and the moderator were added in the second step. Chi-square tests were conducted to determine whether program effects (recidivism) were moderated by gender, ethnicity, age group, age of first crime, prior offenses, and prior violent offenses.

Intervention Effects

Results of the negative binomial regression analyses are presented in Table 2 . Twelve months after the end of treatment and 18 months after program start, we found no significant contribution of condition to self-reported delinquency, adjusting for self-reported delinquency before the start of the program. These analyses indicate that no significant differences were found between the experimental and control groups on participation in self-reported general delinquency and specific types of delinquency (violence, theft, and vandalism).

Means, Standard Deviations, and Intervention Effects of NP Versus CAU, Self-Reports.

Note. All tests are nonsignificant. NP = New Perspectives (experimental group); CAU = care as usual (control group); OR = odds ratio; CI = confidence interval.

Due to missing values at follow-up: NP group ( n = 40) and CAU ( n = 49).

Due to missing values at follow-up: NP group ( n = 43) and CAU ( n = 52).

Table 3 presents the results of the frequency, seriousness, and velocity of recidivism, based on official records, for both conditions. The results show that there were no differences between NP and CAU in the number of rearrests (frequency) and number of violent rearrests (seriousness) at 12 months after program completion and 18 months after program start. Similarly, no significant differences between the two conditions were found in time to rearrest at 12-month follow-up after program completion and at 18-month follow-up (after program start).

Frequency, Seriousness, and Velocity of Recidivism ( n = 47) Versus CAU ( n = 54) by Observation Period, Official Records.

Note . All tests are nonsignificant. NP = New Perspectives (experimental group); CAU = care as usual (control group); OR = odds ratio; CI = confidence interval.

Time to first rearrest is represented by the number of days before first rearrest.

Only for those adolescents who did recidivate.

Cox regression analyses were performed to compare the survival curves of NP and CAU for the whole follow-up period. At the end of the follow-up (on average 875.50 days, SD = 161.94), 30% of the NP group and 41% of the CAU group had been rearrested at least once (see also Figure 1 ). This difference was not significant: The hazard ratio for condition was .691, p = .302, 95% confidence interval (CI) = [0.342, 1.395], indicating no significant differences between the groups.

Survival curve for recidivism for NP and CAU groups separately.

Note. NP = New Perspectives (experimental group); CAU = care as usual (control group).

Moderators of Effectiveness

Moderator tests were conducted to determine whether NP is more beneficial for specific participants. At 18 months after program start, we found no moderating effects of risk index, Wald χ 2 (1) = 0.47, p = .492; prior offenses, Wald χ 2 (1) = 2.56, p = .110; prior violent offenses, Wald χ 2 (1) = 0.08, p = .773; age of first arrest, Wald χ 2 (1) = 1.86, p = .173; gender, Wald χ 2 (1) = 0.04, p = .835; ethnicity, Wald χ 2 (1) = 0.35, p = .554; and age group, Wald χ 2 (1) = 0.31, p = .579. At 12-month follow-up, no significant moderating effect was present for risk index, Wald χ 2 (1) = 0.08, p = .785; offense history, Wald χ 2 (1) = 0.53, p = .466; prior violent offenses, Wald χ 2 (1) = 0.04, p = .840; age of first arrest, Wald χ 2 (1) = 0.79, p = .375; gender, Wald χ 2 (1) = 0.24, p = .627; ethnicity, Wald χ 2 (1) = 0.44, p = .505; and age category, Wald χ 2 (1) = 2.78, p = .096.

For the official judicial data, at 18-month follow-up, no moderator effects were found for prior offenses, hazard ratio = 1.075, p = .935, 95% CI = [0.188, 6.161]; prior violent offenses, hazard ratio = 0.939, p = .945, 95% CI = [0.135, 6.532]; age of first arrest, hazard ratio = 0.734, p = 0.279, 95% CI = [0.420, 1.284]; ethnicity, hazard ratio = 0.466, p = .555, 95% CI = [0.037, 5.874]; age group, hazard ratio = 3.700, p = .115, 95% CI = [0.728, 18.798]; and gender, hazard ratio = 0.650, p = .769, 95% CI = [0.036, 11.632]. Similar results were found at 12-month follow-up, indicating that program effects (survival length) were not significantly moderated by gender, ethnicity, age group, age of first crime, history of offenses, and history of violent offenses.

In the present study, the long-term effects of NP were examined by using adolescent reports and official judicial data on the number of delinquent acts during 12 months after program completion, 18 months after program start, and on average 2.40 years (for official judicial data). The program effectiveness was determined by using an RCT. The present study revealed that NP was not more effective in reducing delinquency levels and recidivism than CAU (during various observation periods). On the basis of self-reports and official reports, we found no significant differences between the conditions in recidivism timing, frequency, and seriousness of reoffending. Adolescents in NP and CAU recidivated at a rate of 30% to 41% during the average follow-up period of well over 2 years.

The present findings are not in line with the meta-analytic study on the effectiveness of preventive interventions ( De Vries, Hoeve, Assink, Stams, & Asscher, 2015 ), in which small positive results were found. However, our results concerning adolescent reports are consistent with findings of the review of Mulvey et al. (1993) , indicating that (secondary) preventive interventions did not produce significant reductions in self-reported delinquency. Moreover, the general results of the present study are in line with other rigorous experimental studies, showing no long-term effects (with a minimum of 1-year follow-up period) of prevention programs on delinquency and recidivism (e.g., Berry, Little, Axford, & Cusick, 2009 ; Cox, 1999 ; Lane, Turner, Fain, & Sehgal, 2005 ). The present study is also consistent with previous findings on the short-term effectiveness study of NP, in which largely the same sample was used (by De Vries, Hoeve, Wibbelink, et al., 2015), indicating that NP did not outperform CAU on self-reported delinquency. Finally, work on the association between research design and study outcomes in the field of criminal justice revealed that studies that adopted a more robust (i.e., stricter) research design generally reported weaker or no effects ( Weisburd, Lum, & Petrosino, 2001 ; Welsh, Peel, Farrington, Elffers, & Braga, 2011 ). Given that the present study’s design, an RCT, is considered to be a strong design in effectiveness research, the present results are in line with the findings of the research of Weisburd et al. (2001) and Welsh et al. (2011) .

There are several explanations why we did not find effects of NP. A first plausible explanation might be the focus and content of the NP program. Although NP can be considered as a theoretically grounded skill building program, NP lacks a focused, structured, and clear therapeutic intervention approach that attempts to engage the youth in a supportive and constructive process of change ( Lipsey, 2009 ). The general coaching style of the NP program (counseling and social work) is comparable with other preventive interventions, such as coaching community programs, education programs, and probation programs, which have not been proven effective in reducing offending in the long term ( Berry et al., 2009 ; Cox, 1999 ; Lane et al., 2005 ; D. B. Wilson, Gottfredson, & Najaka, 2001 ). These preventive interventions do not include specialized effective components of behavioral modeling, contracting, and training parenting skills, which have been proven effective in the treatment of at-risk youth ( De Vries, Hoeve, Assink, et al., 2015 ). In addition, targeting the program at youth whose antisocial behavior is the product of poor bonds with (prosocial) peers, parents, and other important persons in the social network, the area where NP is thought to make a difference seems advisable (see also De Vries, Hoeve, Stams, & Asscher, 2016 ).

Another explanation of not finding evidence to support the effectiveness of NP is that NP was not entirely carried out as intended. Program integrity is an important factor influencing program effectiveness ( Lipsey, 2009 ). A study of De Vries, Hoeve, Asscher, and Stams (2014) examining program integrity levels in treatment of 76 NP adolescents (meeting NP selection criteria) showed that treatment adherence was found to be too low in the aftercare program phase of NP. In 45% of the cases during the aftercare phase, less than 60% of standard services were carried out ( De Vries, Hoeve, Asscher, & Stams, 2014 ). Also, in 46% of the cases, the social network of NP clients was not involved in the treatment process. Durlak and DuPre (2008) recommended minimum levels of program integrity of 60% to reach program effectiveness. Consequently, low levels of treatment adherence (in the aftercare phase) of NP may explain the null effects of NP.

Furthermore, considering the principles of the RNR model, previous evaluation studies suggested a mismatch between program intensity and risk levels of adolescents (e.g., Buysse et al., 2008 ; De Vries et al; Geldorp et al., 2004 ; Loef et al., 2011). De Vries, Hoeve, Wibbelink, et al. (2017) concluded that 28% of the NP adolescents showed a very low risk of reoffending. Given that NP is primarily designed for adolescents whose risk of developing a persistent criminal trajectory is significantly higher than average, the program may be too intensive for adolescents showing (very) low risk levels. According to the risk principle of Andrews and Bonta (2010) and results of a meta-analytic study on preventive interventions ( De Vries, Hoeve, Assink, et al., 2015 ), minimal intervention (low intensity levels) is needed for low-risk offenders. Moreover, a closer look at the NP elements shows that adhering to the risk principle could be improved in the intervention. Although risk assessment has been implemented in the intake phase, it appears not to be a standard procedure, as the clinical practitioners do not always apply risk assessment. Furthermore, the risk assessment instrument used is not validated for the NP group of first offenders. In conclusion, not fully adhering to the risk principle and referral of adolescents with very low risk levels of reoffending to the NP program may negatively influence program effectiveness.

Criminal history is an important predictor of general reoffending ( Cottle et al., 2001 ; Heilbrun, Lee, & Cottle, 2005 ). It is well known that adolescents with higher levels of delinquency risk profit most from intensive programs ( Andrews et al., 1990 ; Lipsey, 2009 ), such as NP. However, we did not found an impact of criminal history on program effects on the basis of self-reported and official judicial reports of delinquency factors (offense history, age of first crime, and a history of violence). As the target group of NP also includes adolescents at onset of a criminal trajectory (predelinquents), future research should examine the influence of a more inclusive risk profile, including dynamic criminogenic factors (such as antisocial peer affiliations and poor family circumstances) on the effectiveness of youth crime prevention. Finally, results of the moderator analyses suggest that effects of NP were about the same for boys and girls, older and younger adolescents, and native Dutch adolescents and adolescents from ethnic minority groups, which is consistent with findings of previous meta-analytic studies ( De Vries, Hoeve, Assink, et al., 2015 ; S. J. Wilson, Lipsey, & Soydan, 2003 ; Zahn et al., 2009 ).

Limitations

Several limitations of the present study should be mentioned. A first limitation is that the sample size of adolescents ( N = 101) was relatively small to detect effects for subgroups. A larger sample size would have increased possibilities to further differentiate between the effects of NP for different subgroups, for example, adolescents from various ethnic backgrounds and various offending risk level groups (low, medium, and high risk of reoffending). Second, we could not assess the influence of program integrity on program effects, as there was no standardized monitoring system of treatment adherence implemented in the (clinical) practice of NP. Therefore, we were not able to relate the level of program integrity to the program outcomes in the present study. Third, we were not able to examine the influence of (static and dynamic criminogenic) risk levels on program effectiveness, while risk profiles were not available for all participants in the present study (only for participants in the NP group). Referral agencies lacked the use of valid risk assessment instruments. A final limitation involves the risk of selection bias, a common methodological problem in experimental (RCT) designs ( Asscher, Deković, Manders, van der Laan, & Prins, 2007 ). Despite relatively high drop-out rates (37%) at first assessment, we found no preexisting differences between participants and nonparticipants on demographic factors.

Conclusions and Recommendations

In summary, the present experimental study reports on the long-term effectiveness of the prevention program NP. We conducted this study in a real-world treatment setting, which contributes to higher levels of external validity. Results of self-report data and official judicial reports provide very little evidence of effectiveness of NP in preventing and reducing persistent (juvenile) delinquency, given that recidivism rates were not lower for those receiving NP than for those receiving CAU.

Those who followed the NP program recidivated later than those receiving CAU. Furthermore, the present study provides several implications for the improvement of prevention programs, such as NP. In order to adhere to the principles of the RNR model, risk assessment should be carried out as a standard procedure, and program integrity could be enhanced. The effectiveness could be enhanced if youth crime prevention programs (such as NP) have a clear program focus, which is based on theoretical models explaining criminal behavior (e.g., targeting poor adolescent–parent bonds), and integrate effective components that are characterized by a strong therapeutic and (cognitive) behavior–oriented approach, such as training parenting skills.

Our study also shows that to gain more knowledge about effective youth crime prevention, government policy makers and purchasers of youth care services should support the continuation of experimental evaluations in naturalistic settings. Given the overall small effects of (secondary) preventive interventions, it is important that research, policy, and clinical practice focus on further testing the effectiveness of promising (theoretically grounded) prevention programs, and on implementation of standardized treatment adherence monitoring systems and reliable risk assessment instruments (to refer youth to the appropriate program).

Flow diagram of the randomization procedure.

Appendix B.

NP Elements and RNR Principles.

Note. NP = New Perspectives.

Source . Adapted from Elling and Melissen (2007) .

Appendix C.

Youth Care Services (Pretest to Posttest, 6 Months), NP and CAU.

Other programs included, for example, “Real Justice group conferencing” and substance use treatment.

“Other ethnic background” consisted of following ethnic backgrounds: Afghan ( n = 1, 1%), African ( n = 7, 7%), Antillean ( n = 3, 3%), Dominican Republic ( n = 1, 1%), Russian ( n = 1, 1%), Turkish ( n = 9, 9%), Kurdish ( n = 1, 1%), and unknown ( n = 9, 9%).

Authors’ Note: Sanne L. A. de Vries is now at Child and Adolescent Studies, Utrecht University, Utrecht, The Netherlands.

Informed Consent: Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Ethical Approval: All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Trial Registration: Dutch trial register number NTR4370. The study is financially supported by a grant from ZonMw, The Netherlands Organisation for Health Research and Development (Grant Number 157004006/80-82435-98-10109). The study is approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Amsterdam (Approval Number 2011-CDE-01).

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by ZonMw, The Netherlands Organisation for Health Research and Development (project 157000.4006).

- Andrews D. A., Bonta J. (2010). Rehabilitating criminal justice policy and practice. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law, 16, 39-55. [ Google Scholar ]

- Andrews D. A., Bonta J., Hoge R. D. (1990). Classification for effective rehabilitation: Rediscovering psychology. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 17, 19-52. [ Google Scholar ]

- Asscher J. J., Deković M., Manders W. A., van der Laan P. H., Prins P. J. (2007). A randomized controlled trial of the effectiveness of multisystemic therapy in the Netherlands: Post-treatment changes and moderator effects. Journal of Experimental Criminology, 9, 169-187. [ Google Scholar ]

- Asscher J. J., Deković M., Manders W., van der Laan P. H., Prins P. J., van Arum S., & Dutch MST Cost-Effectiveness Study Group. (2014). Sustainability of the effects of multisystemic therapy for juvenile delinquents in the Netherlands: Effects on delinquency and recidivism. Journal of Experimental Criminology, 10, 227-243. [ Google Scholar ]

- Artello K., Hayes H., Muschert G., Spencer J. (2015). What do we do with those kids? A critical review of current responses to juvenile delinquency and an alternative. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 24, 1-8. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bandura A., Walters R. H. (1963). Social learning and personality development. New York, NY: Holt, Rinehart, & Winston. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bell V., Lyne S., Kolvin I. (1989). Play group therapy: Processes and patterns and delayed effects. In Schmidt M. H., Remschmidt H. (Eds.), Needs and prospects of child and adolescent psychiatry (pp. 149-163). Bern, Switzerland: Hogrefe & Huber Publishers. [ Google Scholar ]

- Berry V., Little M., Axford N., Cusick G. R. (2009). An evaluation of youth at risk’s coaching for communities programme. Howard Journal of Criminal Justice, 48, 60-75. [ Google Scholar ]

- Buysse W., Van den Andel A., Van Dijk B. (2008). Evaluatie Nieuwe Perspectieven Amersfoort 2005-2007. Amsterdam: DSP-Groep BV. [ Google Scholar ]

- Clingempeel W. G., Henggeler S. W. (2002). Randomized clinical trials, developmental theory, and antisocial youth: Guidelines for research. Development and Psychopathology, 14, 695-711. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cohen J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. [ Google Scholar ]

- Cottle C. C., Lee R. J., Heilbrun K. (2001). The prediction of criminal recidivism in juveniles: A meta-analysis. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 28, 367-394. [ Google Scholar ]

- Cox S. M. (1999). An assessment of an alternative education program for at-risk delinquent youth. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 36, 323-336. [ Google Scholar ]

- Deković M., Slagt M. I., Asscher J. J., Boendermaker L., Eichelsheim V. I., Prinzie P. (2011). Effects of early prevention programs on adult criminal offending: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 31, 532-544. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- De Vries L. A., Hoeve M., Asscher J. J., Stams G. J. J. M. (2014). Onderzoek naar de programma-integriteit van Nieuwe Perspectieven in Amsterdam [A Study of Treatment Integrity of New Perspectives in Amsterdam]. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Universiteit van Amsterdam. [ Google Scholar ]

- De Vries L. A., Hoeve M., Assink M., Asscher J. J., Stams G. J. J. M. (2014). The effects of the prevention program “New Perspectives” (NP) on juvenile delinquency and other life domains: Study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. BMC Psychology, 2, 10. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- De Vries L. A., Hoeve M., Assink M., Stams G. J. J. M., Asscher J. J. (2015). Practitioner review: Effective ingredients of prevention programs for youth at risk of persistent juvenile delinquency: Recommendations for clinical practice. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 56, 108-121. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- De Vries L. A., Hoeve M., Stams G. J. J. M., Asscher J. J. (2016). Adolescent-parent attachment and externalizing behavior: The mediating role of individual and social factors. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 44, 283-294. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- De Vries L. A., Hoeve M., Wibbelink C. J. M., Asscher J. J., Stams G. J. J. M. (2017). A randomized controlled trial of the effectiveness of the youth crime prevention program “New Perspectives” (NP): Post-treatment changes and moderator effects. Children and Youth Services Review, 82, 413-426. [ Google Scholar ]

- Durlak J. A., DuPre E. P. (2008). Implementation matters: A review of research on the influence of implementation on program outcomes and the factors affecting implementation. American Journal of Community Psychology, 41, 327-350. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ellis A. (1962). Reason and emotion in psychotherapy. New York: Lyle Stuart [ Google Scholar ]

- Ellis A., Dryden W. (1997). The practice of rational emotive behavior therapy. New York: Springer publishing company. [ Google Scholar ]

- Elling M. W., Melissen M. (2007). Handboek Nieuwe Perspectieven [A Study of Treatment Integrity of New Perspectives in Amsterdam]. Woerden, The Netherlands: Adviesbureau Van Montfoort. [ Google Scholar ]

- Farrington D. P., Ttofi M. M., Lösel F. (2016). Developmental and social prevention. In Weisburd D., Farrington D. P., Gill C. (Eds.), What works in crime prevention and rehabilitation: Lessons from systematic reviews (pp. 15-75). New York: Springer. [ Google Scholar ]

- Farrington D. P., Welsh B. C. (2003). Family-based prevention of offending: A meta-analysis. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Criminology, 36(2), 127-151. [ Google Scholar ]

- Faul F., Erdfelder E., Buchner A., Lang A.-G. (2009). Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behavior Research Methods, 41, 1149-1160. doi: 10.3758/BRM.41.4.1149 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Geldorp M., Groen H., Hilhorst N., Burmann A., Rietveld M. (2004). Evaluatie Nieuwe Perspectieven 1998-2003 [An Evaluation of New Perspectives 1998-2003]. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: DSP-groep. [ Google Scholar ]

- Gill C. (2016). Community interventions. In Weisburd D., Farrington D. P., Gill C. (Eds.), What works in crime prevention and rehabilitation: Lessons from systematic reviews (pp. 77-109). New York: Springer. [ Google Scholar ]

- Heilbrun K., Lee R., Cottle C. C. (2005). Risk factors and intervention outcomes. In Heilbrun K., Goldstein N. S., Redding R. (Eds.), Juvenile delinquency: Prevention, assessment, and intervention (pp. 111-133). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Hipwell A. E., Loeber R. (2006). Do we know which interventions are effective for disruptive and delinquent girls? Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 9, 221-255. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- James C., Asscher J. J., Stams G. J. J. M., Van der Laan P. H. (2014). The effectiveness of the New Perspectives Aftercare Program for juvenile and young adult offenders: Recidivism outcomes. Manuscript submitted for publication. [ Google Scholar ]

- James C., Stams G. J. J., Asscher J. J., De Roo A. K., van der Laan P. H. (2013). Aftercare programs for reducing recidivism among juvenile and young adult offenders: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 33, 263-274. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kazdin A. E. (1993). Adolescent mental health: Prevention and treatment programs. American Psychologist, 48, 127-141. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kumpfer K. L., Alvarado R., Smith P., Bellamy N. (2002). Cultural sensitivity and adaptation in family-based prevention interventions. Prevention Science, 3, 241-246. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lane J., Turner S., Fain T., Sehgal A. (2005). Evaluating an experimental intensive juvenile probation program: Supervision and official outcomes. Crime & Delinquency, 51, 26-52. [ Google Scholar ]

- Lipsey M. W. (2009). The primary factors that characterize effective interventions with juvenile offenders: A meta-analytic overview. Victims & Offenders, 4, 124-147. [ Google Scholar ]

- Loeber R., Burke J. D., Pardini D. A. (2009). Development and etiology of disruptive and delinquent behavior. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 5, 291-310. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Loeber R., Farrington D. P. (Eds.). (1998). Serious and violent juvenile offenders: Risk factors and successful interventions. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE. [ Google Scholar ]

- Loeber R., Wung P., Keenan K., Giroux B., Stouthamer-Loeber M., Van Kammen W. B., Maugham B. (1993). Developmental pathways in disruptive child behavior. Development and Psychopathology, 5, 103-133. [ Google Scholar ]

- Lösel F., Beelmann A. (2003). Effects of child skills training in preventing antisocial behavior: A systematic review of randomized evaluations. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 587(1), 84-109. [ Google Scholar ]

- Miller W. R., Rollnick S. (2002). Motivational interviewing: Preparing people for change (2nd ed.). New York: Guilford Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Mulvey E. P., Arthur M. W., Reppucci N. D. (1993). The prevention and treatment of juvenile delinquency: A review of the research. Clinical Psychology Review, 13, 133-167. [ Google Scholar ]

- Noorda J. J., Veenbaas R. H. (1997). Eindevaluatie Nieuwe Perspectieven Amsterdam West/Nieuw-West [A final Evaluation of New Perspectives Amsterdam West/Nieuw-West]. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Instituut Jeugd en Welzijn, Vrije Universiteit. [ Google Scholar ]

- Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention. (2011). Juvenile arrests 2009. Washington, DC: Department of Justice. [ Google Scholar ]

- Parhar K. P., Wormith S. W., Derkzen D. M., Beauregard A. M. (2008). Offender coercion in treatment: A meta-analysis of effectiveness. Criminal Justice and Behaviour, 35, 1109-1135. [ Google Scholar ]

- Piquero A. R., Farrington D. P., Welsh B. C., Tremblay R., Jennings W. G. (2009). Effects of early family/parent training programs on antisocial behavior and delinquency. Journal of Experimental Criminology, 5, 83-120. [ Google Scholar ]

- Prochaska J. O., Velicer W. F. (1997). The transtheoretical model of health behavior change. American Journal of Health Promotion, 12, 38-48. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Stevens G. W., Vollebergh W. A. (2008). Mental health in migrant children. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 49, 276-294. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Thornberry T. P., Krohn M. D. (2003). Comparison of self-report and official data for measuring crime. In Pepper J. V., Petrie C. V. (Eds.), Measurement problems in criminal justice research (pp. 43-94). Washington, DC: National Research Council. [ Google Scholar ]

- Van der Laan A. M., Blom M. (2006). Jeugddelinquentie: risico’s en bescherming. Bevindingen uit de WODC Monitor Zelfgerapporteerde Jeugdcriminaliteit 2005 [Juvenile Delinquency: Risks and Protection. Results of the WODC Juvenile Delinquency Self Report Monitor 2005]. Den Haag, The Netherlands: Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek- en Documentatiecentrum. [ Google Scholar ]

- Van der Laan A. M., Blom M. (2011). Jeugdcriminaliteit in de periode 1996-2010 [Juvenile Delinquency 1996-2010]. Den Haag, The Netherlands: Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek- en Documentatiecentrum. [ Google Scholar ]

- Van der Laan A. M., Blom M., Kleemans E. R. (2009). Exploring long-term and short-term risk factors for serious delinquency. European Journal of Criminology, 6, 419-438. [ Google Scholar ]

- Van der Put C. E., Deković M., Stams G. J., Van der Laan P. H., Hoeve M., Van Amelsfort L. (2011). Changes in risk factors during adolescence implications for risk assessment. Criminal Justice and Behaviour, 38, 248-262. [ Google Scholar ]

- Wartna B. S. J., Blom M., Tollenaar N. (2011). The Dutch recidivism monitor [Detention at young age]. The Hague, The Netherlands: Research and Documentation Centre. [ Google Scholar ]

- Wartna B. S. J., Harbachi S. E., Van der Laan A. M. (2005). Jong vast. Boom. [ Google Scholar ]

- Weisburd D., Lum C. M., Petrosino A. (2001). Does research design affect study outcomes in criminal justice? The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 578, 50-70. doi: 10.1177/000271620157800104 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Weisz J. R., Jensen-Doss A., Hawley K. M. (2006). Evidence-based youth psychotherapies versus usual clinical care: a meta-analysis of direct comparisons. American Psychologist, 61, 671. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Welsh B. C., Loeber R., Stevens B. R., Stouthamer-Loeber M., Cohen M. A., Farrington D. P. (2008). Costs of juvenile crime in urban areas: A longitudinal perspective. Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice, 6, 3-27. [ Google Scholar ]

- Welsh B. C., Peel M. E., Farrington D. P., Elffers H., Braga A. A. (2011). Research design influence on study outcomes in crime and justice: A partial replication with public area surveillance. Journal of Experimental Criminology, 7, 183-198. [ Google Scholar ]

- Wilson H. A., Hoge R. D. (2012). The effect of youth diversion programs on recidivism: A meta-analytic review. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 40(5), 497-518. [ Google Scholar ]

- Wilson D. B., Gottfredson D. C., Najaka S. S. (2001). School-based prevention of problem behaviors: A meta-analysis. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 17, 247-272. [ Google Scholar ]

- Wilson S. J., Lipsey M. W., Soydan H. (2003). Are mainstream programs for juvenile delinquency less effective with minority youth than majority youth? A meta-analysis of outcomes research. Research on Social Work Practice, 13, 3-26. [ Google Scholar ]

- Zahn M. A., Day J. C., Mihalic S. F., Tichavsky L. (2009). Determining what works for girls in the juvenile justice system: A summary of evaluation evidence. Crime & Delinquency, 55, 266-293. [ Google Scholar ]

- View on publisher site

- PDF (980.0 KB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

IMAGES