- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 04 February 2020

Marijuana legalization and historical trends in marijuana use among US residents aged 12–25: results from the 1979–2016 National Survey on drug use and health

- Xinguang Chen 1 ,

- Xiangfan Chen 2 &

- Hong Yan 2

BMC Public Health volume 20 , Article number: 156 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

111k Accesses

82 Citations

81 Altmetric

Metrics details

Marijuana is the most commonly used illicit drug in the United States. More and more states legalized medical and recreational marijuana use. Adolescents and emerging adults are at high risk for marijuana use. This ecological study aims to examine historical trends in marijuana use among youth along with marijuana legalization.

Data ( n = 749,152) were from the 31-wave National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH), 1979–2016. Current marijuana use, if use marijuana in the past 30 days, was used as outcome variable. Age was measured as the chronological age self-reported by the participants, period was the year when the survey was conducted, and cohort was estimated as period subtracted age. Rate of current marijuana use was decomposed into independent age, period and cohort effects using the hierarchical age-period-cohort (HAPC) model.

After controlling for age, cohort and other covariates, the estimated period effect indicated declines in marijuana use in 1979–1992 and 2001–2006, and increases in 1992–2001 and 2006–2016. The period effect was positively and significantly associated with the proportion of people covered by Medical Marijuana Laws (MML) (correlation coefficients: 0.89 for total sample, 0.81 for males and 0.93 for females, all three p values < 0.01), but was not significantly associated with the Recreational Marijuana Laws (RML). The estimated cohort effect showed a historical decline in marijuana use in those who were born in 1954–1972, a sudden increase in 1972–1984, followed by a decline in 1984–2003.

The model derived trends in marijuana use were coincident with the laws and regulations on marijuana and other drugs in the United States since the 1950s. With more states legalizing marijuana use in the United States, emphasizing responsible use would be essential to protect youth from using marijuana.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

Marijuana use and laws in the united states.

Marijuana is one of the most commonly used drugs in the United States (US) [ 1 ]. In 2015, 8.3% of the US population aged 12 years and older used marijuana in the past month; 16.4% of adolescents aged 12–17 years used in lifetime and 7.0% used in the past month [ 2 ]. The effects of marijuana on a person’s health are mixed. Despite potential benefits (e.g., relieve pain) [ 3 ], using marijuana is associated with a number of adverse effects, particularly among adolescents. Typical adverse effects include impaired short-term memory, cognitive impairment, diminished life satisfaction, and increased risk of using other substances [ 4 ].

Since 1937 when the Marijuana Tax Act was issued, a series of federal laws have been subsequently enacted to regulate marijuana use, including the Boggs Act (1952), Narcotics Control Act (1956), Controlled Substance Act (1970), and Anti-Drug Abuse Act (1986) [ 5 , 6 ]. These laws regulated the sale, possession, use, and cultivation of marijuana [ 6 ]. For example, the Boggs Act increased the punishment of marijuana possession, and the Controlled Substance Act categorized the marijuana into the Schedule I Drugs which have a high potential for abuse, no medical use, and not safe to use without medical supervision [ 5 , 6 ]. These federal laws may have contributed to changes in the historical trend of marijuana use among youth.

Movements to decriminalize and legalize marijuana use

Starting in the late 1960s, marijuana decriminalization became a movement, advocating reformation of federal laws regulating marijuana [ 7 ]. As a result, 11 US states had taken measures to decriminalize marijuana use by reducing the penalty of possession of small amount of marijuana [ 7 ].

The legalization of marijuana started in 1993 when Surgeon General Elder proposed to study marijuana legalization [ 8 ]. California was the first state that passed Medical Marijuana Laws (MML) in 1996 [ 9 ]. After California, more and more states established laws permitting marijuana use for medical and/or recreational purposes. To date, 33 states and the District of Columbia have established MML, including 11 states with recreational marijuana laws (RML) [ 9 ]. Compared with the legalization of marijuana use in the European countries which were more divided that many of them have medical marijuana registered as a treatment option with few having legalized recreational use [ 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 ], the legalization of marijuana in the US were more mixed with 11 states legalized medical and recreational use consecutively, such as California, Nevada, Washington, etc. These state laws may alter people’s attitudes and behaviors, finally may lead to the increased risk of marijuana use, particularly among young people [ 13 ]. Reported studies indicate that state marijuana laws were associated with increases in acceptance of and accessibility to marijuana, declines in perceived harm, and formation of new norms supporting marijuana use [ 14 ].

Marijuana harm to adolescents and young adults

Adolescents and young adults constitute a large proportion of the US population. Data from the US Census Bureau indicate that approximately 60 million of the US population are in the 12–25 years age range [ 15 ]. These people are vulnerable to drugs, including marijuana [ 16 ]. Marijuana is more prevalent among people in this age range than in other ages [ 17 ]. One well-known factor for explaining the marijuana use among people in this age range is the theory of imbalanced cognitive and physical development [ 4 ]. The delayed brain development of youth reduces their capability to cognitively process social, emotional and incentive events against risk behaviors, such as marijuana use [ 18 ]. Understanding the impact of marijuana laws on marijuana use among this population with a historical perspective is of great legal, social and public health significance.

Inconsistent results regarding the impact of marijuana laws on marijuana use

A number of studies have examined the impact of marijuana laws on marijuana use across the world, but reported inconsistent results [ 13 ]. Some studies reported no association between marijuana laws and marijuana use [ 14 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 ], some reported a protective effect of the laws against marijuana use [ 24 , 26 ], some reported mixed effects [ 27 , 28 ], while some others reported a risk effect that marijuana laws increased marijuana use [ 29 , 30 ]. Despite much information, our review of these reported studies revealed several limitations. First of all, these studies often targeted a short time span, ignoring the long period trend before marijuana legalization. Despite the fact that marijuana laws enact in a specific year, the process of legalization often lasts for several years. Individuals may have already changed their attitudes and behaviors before the year when the law is enacted. Therefore, it may not be valid when comparing marijuana use before and after the year at a single time point when the law is enacted and ignoring the secular historical trend [ 19 , 30 , 31 ]. Second, many studies adapted the difference-in-difference analytical approach designated for analyzing randomized controlled trials. No US state is randomized to legalize the marijuana laws, and no state can be established as controls. Thus, the impact of laws cannot be efficiently detected using this approach. Third, since marijuana legalization is a public process, and the information of marijuana legalization in one state can be easily spread to states without the marijuana laws. The information diffusion cannot be ruled out, reducing the validity of the non-marijuana law states as the controls to compare the between-state differences [ 31 ].

Alternatively, evidence derived based on a historical perspective may provide new information regarding the impact of laws and regulations on marijuana use, including state marijuana laws in the past two decades. Marijuana users may stop using to comply with the laws/regulations, while non-marijuana users may start to use if marijuana is legal. Data from several studies with national data since 1996 demonstrate that attitudes, beliefs, perceptions, and use of marijuana among people in the US were associated with state marijuana laws [ 29 , 32 ].

Age-period-cohort modeling: looking into the past with recent data

To investigate historical trends over a long period, including the time period with no data, we can use the classic age-period-cohort modeling (APC) approach. The APC model can successfully discompose the rate or prevalence of marijuana use into independent age, period and cohort effects [ 33 , 34 ]. Age effect refers to the risk associated with the aging process, including the biological and social accumulation process. Period effect is risk associated with the external environmental events in specific years that exert effect on all age groups, representing the unbiased historical trend of marijuana use which controlling for the influences from age and birth cohort. Cohort effect refers to the risk associated with the specific year of birth. A typical example is that people born in 2011 in Fukushima, Japan may have greater risk of cancer due to the nuclear disaster [ 35 ], so a person aged 80 in 2091 contains the information of cancer risk in 2011 when he/she was born. Similarly, a participant aged 25 in 1979 contains information on the risk of marijuana use 25 years ago in 1954 when that person was born. With this method, we can describe historical trends of marijuana use using information stored by participants in older ages [ 33 ]. The estimated period and cohort effects can be used to present the unbiased historical trend of specific topics, including marijuana use [ 34 , 36 , 37 , 38 ]. Furthermore, the newly established hierarchical APC (HAPC) modeling is capable of analyzing individual-level data to provide more precise measures of historical trends [ 33 ]. The HAPC model has been used in various fields, including social and behavioral science, and public health [ 39 , 40 ].

Several studies have investigated marijuana use with APC modeling method [ 17 , 41 , 42 ]. However, these studies covered only a small portion of the decades with state marijuana legalization [ 17 , 42 ]. For example, the study conducted by Miech and colleagues only covered periods from 1985 to 2009 [ 17 ]. Among these studies, one focused on a longer state marijuana legalization period, but did not provide detailed information regarding the impact of marijuana laws because the survey was every 5 years and researchers used a large 5-year age group which leads to a wide 10-year birth cohort. The averaging of the cohort effects in 10 years could reduce the capability of detecting sensitive changes of marijuana use corresponding to the historical events [ 41 ].

Purpose of the study

In this study, we examined the historical trends in marijuana use among youth using HAPC modeling to obtain the period and cohort effects. These two effects provide unbiased and independent information to characterize historical trends in marijuana use after controlling for age and other covariates. We conceptually linked the model-derived time trends to both federal and state laws/regulations regarding marijuana and other drug use in 1954–2016. The ultimate goal is to provide evidence informing federal and state legislation and public health decision-making to promote responsible marijuana use and to protect young people from marijuana use-related adverse consequences.

Materials and methods

Data sources and study population.

Data were derived from 31 waves of National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH), 1979–2016. NSDUH is a multi-year cross-sectional survey program sponsored by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. The survey was conducted every 3 years before 1990, and annually thereafter. The aim is to provide data on the use of tobacco, alcohol, illicit drug and mental health among the US population.

Survey participants were noninstitutionalized US civilians 12 years of age and older. Participants were recruited by NSDUH using a multi-stage clustered random sampling method. Several changes were made to the NSDUH after its establishment [ 43 ]. First, the name of the survey was changed from the National Household Survey on Drug Abuse (NHSDA) to NSDUH in 2002. Second, starting in 2002, adolescent participants receive $30 as incentives to improve the response rate. Third, survey mode was changed from personal interviews with self-enumerated answer sheets (before 1999) to the computer-assisted person interviews (CAPI) and audio computer-assisted self-interviews (ACASI) (since 1999). These changes may confound the historical trends [ 43 ], thus we used two dummy variables as covariates, one for the survey mode change in 1999 and another for the survey method change in 2002 to control for potential confounding effect.

Data acquisition

Data were downloaded from the designated website ( https://nsduhweb.rti.org/respweb/homepage.cfm ). A database was used to store and merge the data by year for analysis. Among all participants, data for those aged 12–25 years ( n = 749,152) were included. We excluded participants aged 26 and older because the public data did not provide information on single or two-year age that was needed for HAPC modeling (details see statistical analysis section). We obtained approval from the Institutional Review Board at the University of Florida to conduct this study.

Variables and measurements

Current marijuana use: the dependent variable. Participants were defined as current marijuana users if they reported marijuana use within the past 30 days. We used the variable harmonization method to create a comparable measure across 31-wave NSDUH data [ 44 ]. Slightly different questions were used in NSDUH. In 1979–1993, participants were asked: “When was the most recent time that you used marijuana or hash?” Starting in 1994, the question was changed to “How long has it been since you last used marijuana or hashish?” To harmonize the marijuana use variable, participants were coded as current marijuana users if their response to the question indicated the last time to use marijuana was within past 30 days.

Chronological age, time period and birth cohort were the predictors. (1) Chronological age in years was measured with participants’ age at the survey. APC modeling requires the same age measure for all participants [ 33 ]. Since no data by single-year age were available for participants older than 21, we grouped all participants into two-year age groups. A total of 7 age groups, 12–13, ..., 24–25 were used. (2) Time period was measured with the year when the survey was conducted, including 1979, 1982, 1985, 1988, 1990, 1991... 2016. (3). Birth cohort was the year of birth, and it was measured by subtracting age from the survey year.

The proportion of people covered by MML: This variable was created by dividing the population in all states with MML over the total US population. The proportion was computed by year from 1996 when California first passed the MML to 2016 when a total of 29 states legalized medical marijuana use. The estimated proportion ranged from 12% in 1996 to 61% in 2016. The proportion of people covered by RML: This variable was derived by dividing the population in all states with RML with the total US population. The estimated proportion ranged from 4% in 2012 to 21% in 2016. These two variables were used to quantitatively assess the relationships between marijuana laws and changes in the risk of marijuana use.

Covariates: Demographic variables gender (male/female) and race/ethnicity (White, Black, Hispanic and others) were used to describe the study sample.

Statistical analysis

We estimated the prevalence of current marijuana use by year using the survey estimation method, considering the complex multi-stage cluster random sampling design and unequal probability. A prevalence rate is not a simple indicator, but consisting of the impact of chronological age, time period and birth cohort, named as age, period and cohort effects, respectively. Thus, it is biased if a prevalence rate is directly used to depict the historical trend. HAPC modeling is an epidemiological method capable of decomposing prevalence rate into mutually independent age, period and cohort effects with individual-level data, while the estimated period and cohort effects provide an unbiased measure of historical trend controlling for the effects of age and other covariates. In this study, we analyzed the data using the two-level HAPC cross-classified random-effects model (CCREM) [ 36 ]:

Where M ijk represents the rate of marijuana use for participants in age group i (12–13, 14,15...), period j (1979, 1982,...) and birth cohort k (1954–55, 1956–57...); parameter α i (age effect) was modeled as the fixed effect; and parameters β j (period effect) and γ k (cohort effect) were modeled as random effects; and β m was used to control m covariates, including the two dummy variables assessing changes made to the NSDUH in 1999 and 2002, respectively.

The HAPC modeling analysis was executed using the PROC GLIMMIX. Sample weights were included to obtain results representing the total US population aged 12–25. A ridge-stabilized Newton-Raphson algorithm was used for parameter estimation. Modeling analysis was conducted for the overall sample, stratified by gender. The estimated age effect α i , period β j and cohort γ k (i.e., the log-linear regression coefficients) were directly plotted to visualize the pattern of change.

To gain insight into the relationship between legal events and regulations at the national level, we listed these events/regulations along with the estimated time trends in the risk of marijuana from HAPC modeling. To provide a quantitative measure, we associated the estimated period effect with the proportions of US population living with MML and RML using Pearson correlation. All statistical analyses for this study were conducted using the software SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Sample characteristics

Data for a total of 749,152 participants (12–25 years old) from all 31-wave NSDUH covering a 38-year period were analyzed. Among the total sample (Table 1 ), 48.96% were male and 58.78% were White, 14.84% Black, and 18.40% Hispanic.

Prevalence rate of current marijuana use

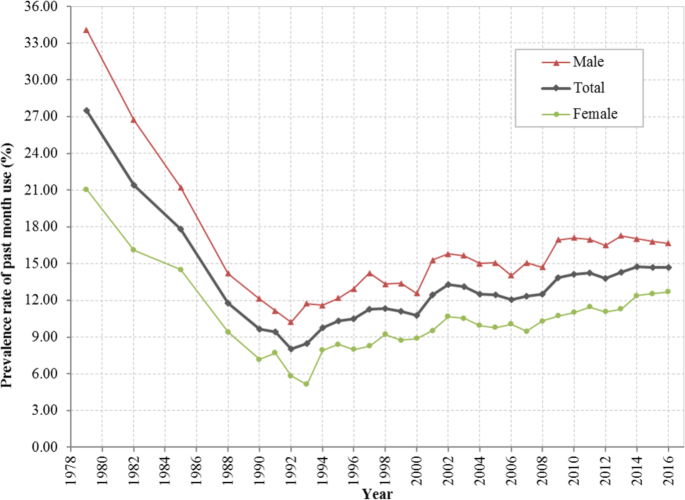

As shown in Fig. 1 , the estimated prevalence rates of current marijuana use from 1979 to 2016 show a “V” shaped pattern. The rate was 27.57% in 1979, it declined to 8.02% in 1992, followed by a gradual increase to 14.70% by 2016. The pattern was the same for both male and female with males more likely to use than females during the whole period.

Prevalence rate (%) of current marijuana use among US residents 12 to 25 years of age during 1979–2016, overall and stratified by gender. Derived from data from the 1979–2016 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH)

HAPC modeling and results

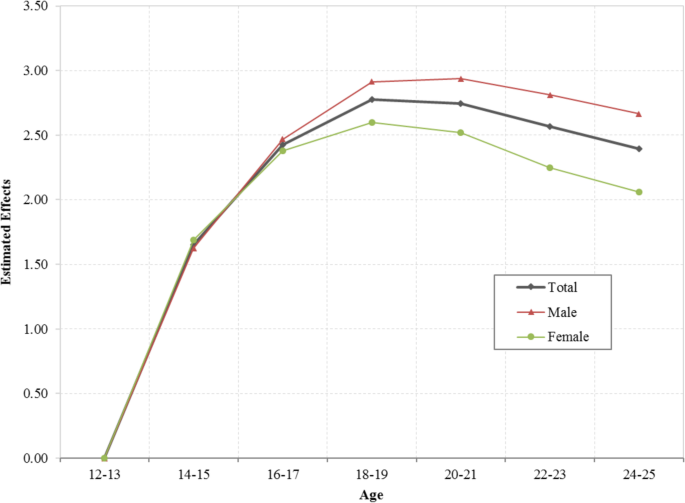

Estimated age effects α i from the CCREM [ 1 ] for current marijuana use are presented in Fig. 2 . The risk by age shows a 2-phase pattern –a rapid increase phase from ages 12 to 19, followed by a gradually declining phase. The pattern was persistent for the overall sample and for both male and female subsamples.

Age effect for the risk of current marijuana use, overall and stratified by male and female, estimated with hierarchical age-period-cohort modeling method with 31 waves of NSDUH data during 1979–2016. Age effect α i were log-linear regression coefficients estimated using CCREM (1), see text for more details

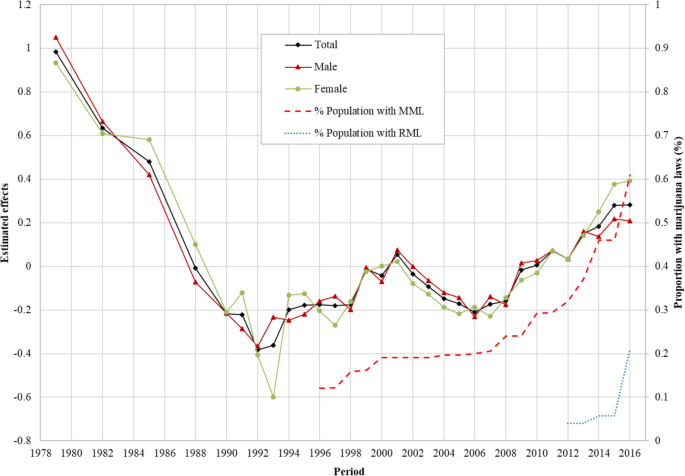

The estimated period effects β j from the CCREM [ 1 ] are presented in Fig. 3 . The period effect reflects the risk of current marijuana use due to significant events occurring over the period, particularly federal and state laws and regulations. After controlling for the impacts of age, cohort and other covariates, the estimated period effect indicates that the risk of current marijuana use had two declining trends (1979–1992 and 2001–2006), and two increasing trends (1992–2001 and 2006–2016). Epidemiologically, the time trends characterized by the estimated period effects in Fig. 3 are more valid than the prevalence rates presented in Fig. 1 because the former was adjusted for confounders while the later was not.

Period effect for the risk of marijuana use for US adolescents and young adults, overall and by male/female estimated with hierarchical age-period-cohort modeling method and its correlation with the proportion of US population covered by Medical Marijuana Laws and Recreational Marijuana Laws. Period effect β j were log-linear regression coefficients estimated using CCREM (1), see text for more details

Correlation of the period effect with proportions of the population covered by marijuana laws: The Pearson correlation coefficient of the period effect with the proportions of US population covered by MML during 1996–2016 was 0.89 for the total sample, 0.81 for male and 0.93 for female, respectively ( p < 0.01 for all). The correlation between period effect and proportion of US population covered by RML was 0.64 for the total sample, 0.59 for male and 0.49 for female ( p > 0.05 for all).

Likewise, the estimated cohort effects γ k from the CCREM [ 1 ] are presented in Fig. 4 . The cohort effect reflects changes in the risk of current marijuana use over the period indicated by the year of birth of the survey participants after the impacts of age, period and other covariates are adjusted. Results in the figure show three distinctive cohorts with different risk patterns of current marijuana use during 1954–2003: (1) the Historical Declining Cohort (HDC): those born in 1954–1972, and characterized by a gradual and linear declining trend with some fluctuations; (2) the Sudden Increase Cohort (SIC): those born from 1972 to 1984, characterized with a rapid almost linear increasing trend; and (3) the Contemporary Declining Cohort (CDC): those born during 1984 and 2003, and characterized with a progressive declining over time. The detailed results of HAPC modeling analysis were also shown in Additional file 1 : Table S1.

Cohort effect for the risk of marijuana use among US adolescents and young adults born during 1954–2003, overall and by male/female, estimated with hierarchical age-period-cohort modeling method. Cohort effect γ k were log-linear regression coefficients estimated using CCREM (1), see text for more details

This study provides new data regarding the risk of marijuana use in youth in the US during 1954–2016. This is a period in the US history with substantial increases and declines in drug use, including marijuana; accompanied with many ups and downs in legal actions against drug use since the 1970s and progressive marijuana legalization at the state level from the later 1990s till today (see Additional file 1 : Table S2). Findings of the study indicate four-phase period effect and three-phase cohort effect, corresponding to various historical events of marijuana laws, regulations and social movements.

Coincident relationship between the period effect and legal drug control

The period effect derived from the HAPC model provides a net effect of the impact of time on marijuana use after the impact of age and birth cohort were adjusted. Findings in this study indicate that there was a progressive decline in the period effect during 1979 and 1992. This trend was corresponding to a period with the strongest legal actions at the national level, the War on Drugs by President Nixon (1969–1974) President Reagan (1981–1989) [ 45 ], and President Bush (1989) [ 45 ],and the Anti-Drug Abuse Act (1986) [ 5 ].

The estimated period effect shows an increasing trend in 1992–2001. During this period, President Clinton advocated for the use of treatment to replace incarceration (1992) [ 45 ], Surgeon General Elders proposed to study marijuana legalization (1993–1994) [ 8 ], President Clinton’s position of the need to re-examine the entire policy against people who use drugs, and decriminalization of marijuana (2000) [ 45 ] and the passage of MML in eight US states.

The estimated period effect shows a declining trend in 2001–2006. Important laws/regulations include the Student Drug Testing Program promoted by President Bush, and the broadened the public schools’ authority to test illegal drugs among students given by the US Supreme Court (2002) [ 46 ].

The estimated period effect increases in 2006–2016. This is the period when the proportion of the population covered by MML progressively increased. This relation was further proved by a positive correlation between the estimated period effect and the proportion of the population covered by MML. In addition, several other events occurred. For example, over 500 economists wrote an open letter to President Bush, Congress and Governors of the US and called for marijuana legalization (2005) [ 47 ], and President Obama ended the federal interference with the state MML, treated marijuana as public health issues, and avoided using the term of “War on Drugs” [ 45 ]. The study also indicates that the proportion of population covered by RML was positively associated with the period effect although not significant which may be due to the limited number of data points of RML. Future studies may follow up to investigate the relationship between RML and rate of marijuana use.

Coincident relationship between the cohort effect and legal drug control

Cohort effect is the risk of marijuana use associated with the specific year of birth. People born in different years are exposed to different laws, regulations in the past, therefore, the risk of marijuana use for people may differ when they enter adolescence and adulthood. Findings in this study indicate three distinctive cohorts: HDC (1954–1972), SIC (1972–1984) and CDC (1984–2003). During HDC, the overall level of marijuana use was declining. Various laws/regulations of drug use in general and marijuana in particular may explain the declining trend. First, multiple laws passed to regulate the marijuana and other substance use before and during this period remained in effect, for example, the Marijuana Tax Act (1937), the Boggs Act (1952), the Narcotics Control Act (1956) and the Controlled Substance Act (1970). Secondly, the formation of government departments focusing on drug use prevention and control may contribute to the cohort effect, such as the Bureau of Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs (1968) [ 48 ]. People born during this period may be exposed to the macro environment with laws and regulations against marijuana, thus, they may be less likely to use marijuana.

Compared to people born before 1972, the cohort effect for participants born during 1972 and 1984 was in coincidence with the increased risk of using marijuana shown as SIC. This trend was accompanied by the state and federal movements for marijuana use, which may alter the social environment and public attitudes and beliefs from prohibitive to acceptive. For example, seven states passed laws to decriminalize the marijuana use and reduced the penalty for personal possession of small amount of marijuana in 1976 [ 7 ]. Four more states joined the movement in two subsequent years [ 7 ]. People born during this period may have experienced tolerated environment of marijuana, and they may become more acceptable of marijuana use, increasing their likelihood of using marijuana.

A declining cohort CDC appeared immediately after 1984 and extended to 2003. This declining cohort effect was corresponding to a number of laws, regulations and movements prohibiting drug use. Typical examples included the War on Drugs initiated by President Nixon (1980s), the expansion of the drug war by President Reagan (1980s), the highly-publicized anti-drug campaign “Just Say No” by First Lady Nancy Reagan (early 1980s) [ 45 ], and the Zero Tolerance Policies in mid-to-late 1980s [ 45 ], the Anti-Drug Abuse Act (1986) [ 5 ], the nationally televised speech of War on Drugs declared by President Bush in 1989 and the escalated War on Drugs by President Clinton (1993–2001) [ 45 ]. Meanwhile many activities of the federal government and social groups may also influence the social environment of using marijuana. For example, the Federal government opposed to legalize the cultivation of industrial hemp, and Federal agents shut down marijuana sales club in San Francisco in 1998 [ 48 ]. Individuals born in these years grew up in an environment against marijuana use which may decrease their likelihood of using marijuana when they enter adolescence and young adulthood.

This study applied the age-period-cohort model to investigate the independent age, period and cohort effects, and indicated that the model derived trends in marijuana use among adolescents and young adults were coincident with the laws and regulations on marijuana use in the United States since the 1950s. With more states legalizing marijuana use in the United States, emphasizing responsible use would be essential to protect youth from using marijuana.

Limitations

This study has limitations. First, study data were collected through a household survey, which is subject to underreporting. Second, no causal relationship can be warranted using cross-sectional data, and further studies are needed to verify the association between the specific laws/regulation and the risk of marijuana use. Third, data were available to measure single-year age up to age 21 and two-year age group up to 25, preventing researchers from examining the risk of marijuana use for participants in other ages. Lastly, data derived from NSDUH were nation-wide, and future studies are needed to analyze state-level data and investigate the between-state differences. Although a systematic review of all laws and regulations related to marijuana and other drugs is beyond the scope of this study, findings from our study provide new data from a historical perspective much needed for the current trend in marijuana legalization across the nation to get the benefit from marijuana while to protect vulnerable children and youth in the US. It provides an opportunity for stack-holders to make public decisions by reviewing the findings of this analysis together with the laws and regulations at the federal and state levels over a long period since the 1950s.

Availability of data and materials

The data of the study are available from the designated repository ( https://nsduhweb.rti.org/respweb/homepage.cfm ).

Abbreviations

Audio computer-assisted self-interviews

Age-period-cohort modeling

Computer-assisted person interviews

Cross-classified random-effects model

Contemporary Declining Cohort

Hierarchical age-period-cohort

Historical Declining Cohort

Medical Marijuana Laws

National Household Survey on Drug Abuse

National Survey on Drug Use and Health

Recreational Marijuana Laws

Sudden Increase Cohort

The United States

CDC. Marijuana and Public Health. 2017. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/marijuana/index.htm . Accessed 13 June 2018.

SAMHSA. Results from the 2015 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Detailed Tables. 2016 [cited 2018 Jan 31]. Available from: https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUH-DetTabs-2015/NSDUH-DetTabs-2015/NSDUH-DetTabs-2015.htm

Committee on the Health Effects of Marijuana: An Evidence Review and Research Agenda, Board on Population Health and Public Health Practice, Health and Medicine Division, National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. The health effects of cannabis and cannabinoids: the current state of evidence and recommendations for research. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press; 2017.

Collins C. Adverse health effects of marijuana use. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(9):879.

PubMed Google Scholar

Belenko SR. Drugs and drug policy in America: a documentary history. Westport: Greenwood Press; 2000.

Google Scholar

Gerber RJ. Legalizing marijuana: Drug policy reform and prohibition politics. Westport: Praeger; 2004.

Single EW. The impact of marijuana decriminalization: an update. J Public Health Policy. 1989:456–66.

Article CAS Google Scholar

SFChronicle. Ex-surgeon general backed legalizing marijuana before it was cool [Internet]. 2016 [cited 2018 Oct 7]. Available from: https://www.sfchronicle.com/business/article/Ex-surgeon-general-backed-legalizing-marijuana-6799348.php

PROCON. 31 Legal Medical Marijuana States and DC. 2018 [cited 2018 Oct 4]. Available from: https://medicalmarijuana.procon.org/view.resource.php?resourceID=000881

Bifulco M, Pisanti S. Medicinal use of cannabis in Europe: the fact that more countries legalize the medicinal use of cannabis should not become an argument for unfettered and uncontrolled use. EMBO Rep. 2015;16(2):130–2.

European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction. Models for the legal supply of cannabis: recent developments (Perspectives on drugs). 2016. Available from: http://www.emcdda.europa.eu/publications/pods/legal-supply-of-cannabis . Accessed 10 Jan 2020.

European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction. Cannabis policy: status and recent developments. 2017. Available from: http://www.emcdda.europa.eu/topics/cannabis-policy_en#section2 . Accessed 10 Jan 2020.

Hughes B, Matias J, Griffiths P. Inconsistencies in the assumptions linking punitive sanctions and use of cannabis and new psychoactive substances in Europe. Addiction. 2018;113(12):2155–7.

Article Google Scholar

Anderson DM, Hansen B, Rees DI. Medical marijuana laws and teen marijuana use. Am Law Econ Rev. 2015;17(2):495-28.

United States Census Bureau. Annual Estimates of the Resident Population by Single Year of Age and Sex for the United States, States, and Puerto Rico Commonwealth: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2016 2016 Population Estimates. 2017 [cited 2018 Mar 14]. Available from: https://factfinder.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?src=bkmk

Chen X, Yu B, Lasopa S, Cottler LB. Current patterns of marijuana use initiation by age among US adolescents and emerging adults: implications for intervention. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2017;43(3):261–70.

Miech R, Koester S. Trends in U.S., past-year marijuana use from 1985 to 2009: an age-period-cohort analysis. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;124(3):259–67.

Steinberg L. The influence of neuroscience on US supreme court decisions about adolescents’ criminal culpability. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2013;14(7):513–8.

Sarvet AL, Wall MM, Fink DS, Greene E, Le A, Boustead AE, et al. Medical marijuana laws and adolescent marijuana use in the United States: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Addiction. 2018;113(6):1003–16.

Hasin DS, Wall M, Keyes KM, Cerdá M, Schulenberg J, O’Malley PM, et al. Medical marijuana laws and adolescent marijuana use in the USA from 1991 to 2014: results from annual, repeated cross-sectional surveys. Lancet Psychiatry. 2015;2(7):601–8.

Pacula RL, Chriqui JF, King J. Marijuana decriminalization: what does it mean in the United States? National Bureau of Economic Research; 2003.

Donnelly N, Hall W, Christie P. The effects of the Cannabis expiation notice system on the prevalence of cannabis use in South Australia: evidence from the National Drug Strategy Household Surveys 1985-95. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2000;19(3):265–9.

Gorman DM, Huber JC. Do medical cannabis laws encourage cannabis use? Int J Drug Policy. 2007;18(3):160–7.

Lynne-Landsman SD, Livingston MD, Wagenaar AC. Effects of state medical marijuana laws on adolescent marijuana use. Am J Public Health. 2013 Aug;103(8):1500–6.

Pacula RL, Powell D, Heaton P, Sevigny EL. Assessing the effects of medical marijuana laws on marijuana and alcohol use: the devil is in the details. National Bureau of Economic Research; 2013.

Harper S, Strumpf EC, Kaufman JS. Do medical marijuana laws increase marijuana use? Replication study and extension. Ann Epidemiol. 2012;22(3):207–12.

Stolzenberg L, D’Alessio SJ, Dariano D. The effect of medical cannabis laws on juvenile cannabis use. Int J Drug Policy. 2016;27:82–8.

Wang GS, Roosevelt G, Heard K. Pediatric marijuana exposures in a medical marijuana state. JAMA Pediatr. 2013;167(7):630–3.

Wall MM, Poh E, Cerdá M, Keyes KM, Galea S, Hasin DS. Adolescent marijuana use from 2002 to 2008: higher in states with medical marijuana laws, cause still unclear. Ann Epidemiol. 2011;21(9):714–6.

Chen X, Yu B, Stanton B, Cook RL, Chen D-GD, Okafor C. Medical marijuana laws and marijuana use among U.S. adolescents: evidence from michigan youth risk behavior surveillance data. J Drug Educ. 2018;47237918803361.

Chen X. Information diffusion in the evaluation of medical marijuana laws’ impact on risk perception and use. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(12):e8.

Chen X, Yu B, Stanton B, Cook RL, Chen DG, Okafor C. Medical marijuana laws and marijuana use among US adolescents: Evidence from Michigan youth risk behavior surveillance data. J Drug Educ. 2018;48(1-2):18-35.

Yang Y, Land K. Age-Period-Cohort Analysis: New Models, Methods, and Empirical Applications. Boca Raton: Chapman and Hall/CRC; 2013.

Yu B, Chen X. Age and birth cohort-adjusted rates of suicide mortality among US male and female youths aged 10 to 19 years from 1999 to 2017. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(9):e1911383.

Akiba S. Epidemiological studies of Fukushima residents exposed to ionising radiation from the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant prefecture--a preliminary review of current plans. J Radiol Prot. 2012;32(1):1–10.

Yang Y, Land KC. Age-period-cohort analysis of repeated cross-section surveys: fixed or random effects? Sociol Methods Res. 2008;36(3):297–326.

O’Brien R. Age-period-cohort models: approaches and analyses with aggregate data. Boca Raton: Chapman and Hall/CRC; 2014.

Book Google Scholar

Chen X, Sun Y, Li Z, Yu B, Gao G, Wang P. Historical trends in suicide risk for the residents of mainland China: APC modeling of the archived national suicide mortality rates during 1987-2012. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2018;54(1):99–110.

Yang Y. Social inequalities in happiness in the United States, 1972 to 2004: an age-period-cohort analysis. Am Sociol Rev. 2008;73(2):204–26.

Reither EN, Hauser RM, Yang Y. Do birth cohorts matter? Age-period-cohort analyses of the obesity epidemic in the United States. Soc Sci Med. 2009;69(10):1439–48.

Kerr WC, Lui C, Ye Y. Trends and age, period and cohort effects for marijuana use prevalence in the 1984-2015 US National Alcohol Surveys. Addiction. 2018;113(3):473–81.

Johnson RA, Gerstein DR. Age, period, and cohort effects in marijuana and alcohol incidence: United States females and males, 1961-1990. Substance Use Misuse. 2000;35(6–8):925–48.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2013 NSDUH: Summary of National Findings, SAMHSA, CBHSQ. 2014 [cited 2018 Sep 23]. Available from: https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUHresultsPDFWHTML2013/Web/NSDUHresults2013.htm

Bauer DJ, Hussong AM. Psychometric approaches for developing commensurate measures across independent studies: traditional and new models. Psychol Methods. 2009;14(2):101–25.

Drug Policy Alliance. A Brief History of the Drug War. 2018 [cited 2018 Sep 27]. Available from: http://www.drugpolicy.org/issues/brief-history-drug-war

NIDA. Drug testing in schools. 2017 [cited 2018 Sep 27]. Available from: https://www.drugabuse.gov/related-topics/drug-testing/faq-drug-testing-in-schools

Wikipedia contributors. Legal history of cannabis in the United States. 2015. Available from: https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Legal_history_of_cannabis_in_the_United_States&oldid=674767854 . Accessed 24 Oct 2017.

NORML. Marijuana law reform timeline. 2015. Available from: http://norml.org/shop/item/marijuana-law-reform-timeline . Accessed 24 Oct 2017.

Download references

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Epidemiology, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL, 32608, USA

Bin Yu & Xinguang Chen

Department of Epidemiology and Health Statistics School of Health Sciences, Wuhan University, Wuhan, 430071, China

Xiangfan Chen & Hong Yan

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

BY designed the study, collected the data, conducted the data analysis, drafted and reviewed the manuscript; XGC designed the study and reviewed the manuscript. XFC and HY reviewed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Hong Yan .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

The study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Florida. Data in the study were public available.

Consent for publication

All authors consented for the publication.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1: table s1..

Estimated Age, Period, Cohort Effects for the Trend of Marijuana Use in Past Month among Adolescents and Emerging Adults Aged 12 to 25 Years, NSDUH, 1979-2016. Table S2. Laws at the federal and state levels related to marijuana use.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Yu, B., Chen, X., Chen, X. et al. Marijuana legalization and historical trends in marijuana use among US residents aged 12–25: results from the 1979–2016 National Survey on drug use and health. BMC Public Health 20 , 156 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-8253-4

Download citation

Received : 15 June 2019

Accepted : 21 January 2020

Published : 04 February 2020

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-8253-4

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Adolescents and young adults

- United States

BMC Public Health

ISSN: 1471-2458

- General enquiries: [email protected]

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Social and Political Factors Associated With State-Level Legalization of Cannabis in the United States

Joanne spetz, susan a chapman, timothy bates, matthew jura, laura a schmidt.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

The views expressed in this paper do not necessarily represent those of the National Institute on Drug Abuse or University of California, San Francisco.

Corresponding Author : Joanne Spetz, 3333 California Street, Suite 265, San Francisco, CA 94118, USA. [email protected]

Issue date 2019 Jun 1.

Article reuse guidelines: sagepub.com/journals-permissions

Thirty-three U.S. states and the District of Columbia (DC) have legalized the use of marijuana for medicinal purposes and 10 states and DC have legalized marijuana for adult recreational use. This mirrors an international trend toward relaxing restrictions on marijuana. This paper analyzes patterns in marijuana laws across U.S. states to shed light on the social and political forces behind the liberalization of marijuana policy following a long era of conservatism. Data on U.S. state-level demographics, economic conditions, and cultural and political characteristics are analyzed, as well as establishment of and levels of support for other drug and social policies, to determine whether there are patterns between states that have liberalized marijuana policy versus those that have not. Laws decriminalizing marijuana possession, as well as those authorizing its sale for medical and recreational use, follow the same pattern of diffusion. The analysis points to underlying patterns of demographic, cultural, economic, and political variation linked to marijuana policy liberalization in the U.S. context, which deserve further examination internationally.

Keywords: medical marijuana, marijuana policy, substance control policy

In 2018, Michigan joined eight U.S. states and the District of Columbia (DC) that have legalized the use and possession of marijuana for recreational purposes and Vermont’s legislature passed a bill allowing recreational marijuana possession ( Marijuana Policy Project [MPP], 2018a ). In addition, 33 states and the DC have legalized its use for medicinal purposes ( ProCon.org, 2018a ) and 13 additional U.S. states have decriminalized the possession of marijuana in small amounts, with penalties typically limited to fines or community service ( MPP, 2018a ). Thirteen of the 17 states that do not permit medical or recreational use of marijuana permit high-cannabidiol-low-THC products ( National Conference of State Legislatures, 2018 ). Lawmakers in 23 states considered legislation in 2018 to legalize recreational marijuana for adults ( MPP, 2018b ).

After nearly 100 years of highly restrictive marijuana policies ( Siff, 2014 ), these changes in U.S. marijuana policy over the past two decades are striking. The trend toward state legalization for medical and recreational use has led policy analysts and public health officials to ask whether the U.S. is on a path toward the nationwide legalization of marijuana ( Caulkins, Coulson, Farber, & Vesely, 2012 ; Caulkins, Kilmer, & Kleiman, 2016 ). Patterns in the U.S. reflect a larger international trend toward the legalization and decriminalization of marijuana. Canada, Colombia, the Netherlands, Spain, and Uruguay have legalized marijuana for personal use, although many European countries have resisted liberal marijuana policies ( Berke & Gould, 2018 ; Bretteville-Jensen, 2016 ; Hughes, Quigley, Ballotta, & Griffiths, 2017 ). Many more countries have decriminalized marijuana possession in small amounts for personal use and legalized medical use ( Kilmer & Pacula, 2017 ). The diversity of U.S. states mirrors international diversity: U.S. states each have their own social and political cultures and have substantial effective scope for local decisions within the context of federal law in many domains including alcohol, tobacco, and marijuana control policies. This variation makes the U.S. an instructive case for studying the underlying social and political forces that may be driving nations toward more liberal marijuana policies.

This paper analyzes social and political variation across the U.S. states to investigate factors that could be linked to the rising trend toward dismantling long-standing drug control regimes prohibiting marijuana sales and use. We analyzed data on demographics, economic conditions, and social and political characteristics to determine whether there are patterns between states that have liberalized marijuana policy versus those that have not. We also examined levels of public support for other drug and social policies to learn whether marijuana liberalization is linked to trends in regulatory choices in other policy realms.

Data Collection

We collected data about the passage of state laws that permit retail marijuana sales, authorize marijuana use for medical purposes, and reduce penalties for marijuana possession to an infraction or civil offense from 1973 through 2016. Data were gathered from websites such as Procon.org (2018a) , National Conference of State Legislatures (2018) , and the MPP (2018a) ; public records of state laws; and published papers. When secondary sources provided conflicting information, we contacted state government officials directly to verify information.

Additional data were compiled regarding demographic, economic, and political characteristics of each state in 2014, which was the most recent year for which nearly all variables of interest were available at the time the analysis was conducted. While some variables such as unemployment rates fluctuate over time, the relative levels of these variables across states tend to remain stable. State-level demographic measures included age distribution, racial/ethnic mix ( U.S. Bureau of the Census, 2016 ), immigrant status ( Flood, King, Ruggles, & Warren, 2015 ), education ( Flood et al., 2015 ), religious affiliation ( Pew Research Center, 2015 ), and frequency of attendance at religious services ( Gallup Daily Tracking Survey, 2014 ). Economic characteristics included the unemployment rate ( U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2016 ), share of employment in professional and business services and goods-producing occupations ( U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2014 ), and average household income ( Flood et al., 2015 ).

Political characteristics included whether the state legislature was controlled by the Democratic Party ( Ballotpedia, 2014 ; National Conference of State Legislatures, 2014 ), percentages of the population self-identifying as conservative or liberal ( Gallup Daily Tracking Survey, 2014 ), and whether states allow citizens to place initiatives and referendums on the ballot ( Ballotpedia, 2018 ). Twenty-four states offer initiative or referendum rights to their citizens, and two additional states allow voters to veto legislation by referendum. Initiative and referendum rights exist in 18 of the 24 states west of the Mississippi river, but in only 8 of the 26 states east of the Mississippi river.

We also collected data on whether states have enacted other alcohol and other drug policies: marijuana decriminalization, legal syringe exchange programs ( Law Atlas, 2016 ), a ban on Sunday off-premises sale of alcohol, and alcohol sales tax controls, in which the state sets the price of and gains revenue directly (rather than solely from taxation) from the wholesale or retail system of distribution for the index beverage ( Alcohol Policy Information System, 2018 ). We also tracked other social policies: percentage of population approving of gay marriage ( Flores & Barclay, 2015 ); whether states allow nurse practitioners to practice without physician oversight ( American Association of Nurse Practitioners, 2016 ); abortion restrictiveness ( NARAL, 2018 ); stand-your-ground gun laws (from 2012; FindLaw, n.d. ; ProPublica, 2012 ), which allow individuals to defend themselves with deadly force when threatened; and concealed carry gun laws, which regulate whether permits are required and under what circumstances they can be issued for a citizen to carry a concealed gun ( ProCon.org, 2018b ).

Data Analysis

We examined geographic patterns and time trends of adoption of medical marijuana and recreational marijuana laws. We then compared social, economic, and political characteristics, and drug and social policies, of states that have not passed medical marijuana laws with those that passed medical marijuana laws prior to 2010; states that passed medical marijuana between 2010 and 2018; and states that have legalized recreational marijuana using Mann–Whitney U or Pearson’s χ 2 tests to identify significant differences. Comparisons are also made across these states regarding other drug and social policies.

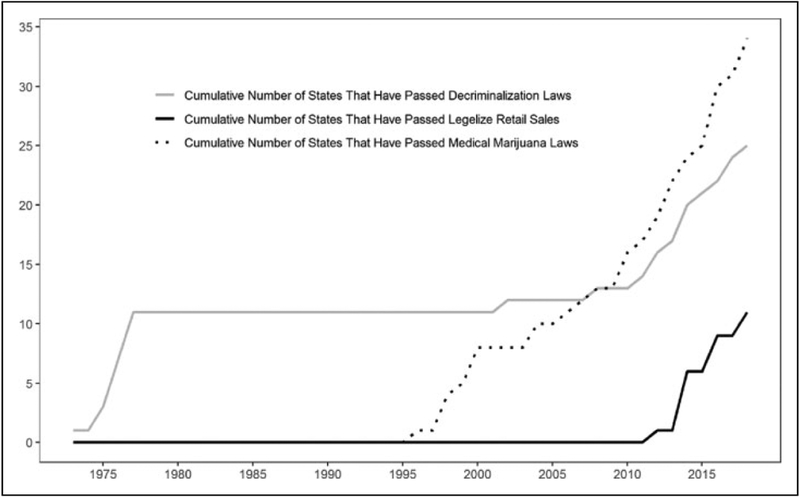

Geographic and Time Trends in U.S. Marijuana Policy

The advent of U.S. states legalizing marijuana for retail sale has roots in a longer wave of marijuana policy liberalization that began in 1973, when the first state law to decriminalize marijuana passed in Oregon ( Figure 1 ). By 1977, 11 states had decriminalized marijuana possession in small amounts. Passage of California’s Proposition 215 in 1996, which legalized marijuana use for medical purposes, initiated a second wave of policy liberalization. By 2000, eight states had passed medical marijuana laws, all but one of which were located in the western U.S.

Trends in U.S. state marijuana policy liberalization (1973–2018).

In 2004, the medical marijuana law trend “jumped coasts” when two states in the northeastern portion of the U.S. passed laws legalizing use for medicinal purposes. After 2004, the passage of new medical marijuana laws occurred in northern central, northeastern, and mid-Atlantic states. States in the south-eastern portions of the U.S., however, resisted medical marijuana laws until 2016, when Florida and Arkansas passed medical marijuana ballot propositions. In 2018, elected representatives in 14 of the remaining 17 states that do not permit medical marijuana considered legislation to establish medical marijuana programs. In only one of these states—Missouri—was there a floor vote on a medical marijuana bill ( MPP, 2018b ); Missouri passed a medical marijuana ballot initiative in November 2018.

In 1972, the first statewide ballot measure to legalize marijuana for adult recreational use was introduced and failed in California. Fourteen years later, Oregon tried with another ballot measure in 1986. Between 2000 and 2014, voters in primarily western states entertained 13 different legalization measures, with successes in Washington (2012), Colorado (2012), Oregon (2014), Alaska (2014), and Washington, DC (2014). In 2016, the legalization trend once again “jumped coasts” with two states in the northeastern U.S., in addition to the western states of California and Nevada. And, in 2018, a northern central state (Michigan) legalized recreational marijuana, along with another northeastern state (Vermont).

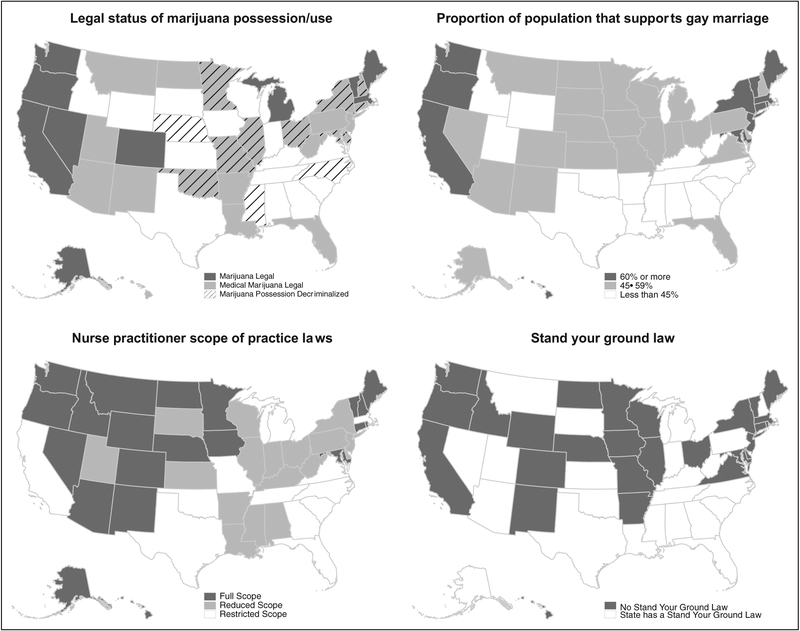

The first quadrant of Figure 2 shows the distinct geographic patterns among states that have liberalized marijuana policies. It shows states in which marijuana possession has been decriminalized (diagonal lines), medical marijuana is legal (gray), and where the sale of marijuana for recreational purposes is permitted (black). States in the northeastern U.S. and on the Pacific coast have more liberal marijuana policies than states in the central and southeastern parts of the country. This map also shows that states that have relaxed marijuana controls in one way tend to do so in others. Those that have legalized medical marijuana are more likely to have decriminalized possession (65% vs. 18%, p < .01) and to have established legal syringe exchange programs (47% vs. 0%, p < .001; Table 1 ). All states in the western and northeastern U.S. have legalized medical marijuana except for Idaho and Wyoming. The northern central states appear to be the next frontier for these laws, with four states having legalized medicinal use since 2008 and one legalizing recreational use in 2018. In contrast, no states in the southeast or southern central regions had adopted a medical marijuana law until 2016, when Arkansas and Florida passed propositions; three additional states in these regions have since passed medical marijuana laws, even though few states have decriminalized marijuana possession and none permit recreational marijuana use or sales.

Maps of marijuana policies, gay marriage support, nurse practitioner independence, and “stand-your-ground” gun laws (2018).

Demographic, Economic, and Political Characteristics of U.S. States, and Other Social and Drug Policies by Marijuana Legalization Status (Percentages and Medians).

Mann–Whitney U test (continuous variables), Pearson’s χ 2 test or Fisher exact test (counts).

National Survey on Drug Use and Health (2014–2015) Restricted-use Data Analysis System; respondents 12+.

Demographic and Social Characteristics

States participating in the trend toward liberalizing marijuana policy are demographically, economically, and politically distinct. The first five columns of Table 1 describe states that legalized medical marijuana prior to 2010 (early adopters) and between 2010 and 2018 (late adopters) compared to those that have not. The last two columns describe states that have legalized recreational marijuana and compare them to states that have not legalized medical marijuana.

Early adopters of medical marijuana had, on average, smaller proportions of Black/African American residents (3.6% vs. 9.2%, p = .013) and larger immigrant populations (12.3% vs. 6.8%, p = .038). Late adopters of medical marijuana also had a larger immigrant population (12.1% vs. 6.8%, p = .036) and a larger Asian population (3% vs. 2%, p = .036). States that have legalized recreational marijuana also had a larger Asian (4.1% vs. 2%, p = .008) and immigrant population (12.3% vs. 6.8%, p = .015). There were no statistically significant differences in the age distribution of the population across states in different marijuana legalization categories. There were also no significant differences in the share of the population with less than 12 years of education.

Residents of early-adopter medical marijuana states were more likely to report that they are Catholic than residents of nonlegal states (20% vs. 12%, p = .018), as were residents of late-adopter (22% vs. 12%, p = .019) and recreational marijuana states (20% vs. 12%, p < .028). Evangelical Protestantism was much less often reported by residents of all categories of legal marijuana states than in nonlegal states (19–23% vs. 31%, p ≤ .001). Residents in states with recreational marijuana were less likely to report they are Mainline Protestant than residents of nonlegal states (13% vs. 16%, p = .027). Early-adopter medical and recreational marijuana states had a larger share of residents who reported no religious affiliation (29–31% vs. 20%, p < .001), but late-adopter medical marijuana states were not significantly different from nonlegal states (22% vs. 20%, p = .147). Residents in all categories of legal marijuana states were less likely to report weekly religious service attendance; the difference was notably larger among early-adopter and recreational states versus nonlegal states (24–26% vs. 35%, p < .001) than for late-adopter states (32% vs. 35%, p = .013). Conversely, residents of all categories of legal marijuana states were more likely to report they seldom or never attended religious services (46–57% vs. 40%, p < .01).

Residents of all categories of legal marijuana states were more likely to have used marijuana in the past month than those in nonlegal states, with the highest rates among early-adopter medical and recreational states (11.5–11.8% vs. 6.5%, p < .001). Late-adopter medical marijuana states also had a higher share of residents who used marijuana in the past month than nonlegal states, but the difference was not as large (7.8% vs. 6.5%, p = .009). These differences could reflect increased marijuana use that resulted from liberal marijuana policies as well as increased likelihood of liberalizing marijuana laws if a larger share of residents already use marijuana; it is not possible to determine a causal relationship.

Economic Characteristics

States with medical and recreational marijuana laws had a smaller share of the workforce employed in goods-producing occupations than nonlegal states (12.7–13.5% vs. 16.2%, p ≤ .003). These states also had a greater share of households with incomes over US$75,000 (21.6%–24.8 % vs. 17.2%, p ≤ .025). There were no significant differences across states in unemployment rates or the share of workers in professional occupations.

Political Characteristics

Among early-adopter medical marijuana states, 77% had legislatures controlled by Democrats in 2014 compared with none among nonlegal states ( p < .001). The difference was even larger among recreational marijuana states (82%, p < .001). Among late-adopter medical marijuana states, less than half had Democrat-controlled legislatures in 2014 (43%, p = .002). A smaller share of the population identified as ideologically “conservative” in all categories of legal marijuana states versus nonlegal states (34–36% vs. 40%, p ≤ .009). A closer look at the time trend reveals that 9 of the 10 states that passed medical marijuana laws between 2010 and 2014 had Democrat-controlled legislatures in 2014; the one Republican-controlled state passed medical marijuana by ballot initiative. Conversely, 9 of the 10 states that passed medical marijuana laws after 2014 had Republican-controlled legislatures in 2014 and three of these had legislatively passed laws.

States that were early adopters of medical marijuana are more likely to allow ballot initiatives and referenda than are nonlegal states (69% vs. 18%, p = .008), as are states with recreational marijuana (82% vs. 18%, p = .001). There was no statistically significant difference in the share of late-adopter medical marijuana states that allow ballot initiatives versus nonlegal states (33% vs. 18%, p = .46). Seven of the first 10 states to establish medical marijuana provisions did so by initiative or referenda. However, the trend has shifted toward legislative approval of medical marijuana, with only 9 of the 21 states passing medical marijuana laws since 2010 doing so by ballot initiative. Recreational marijuana laws have passed by ballot initiative in all but one state (Vermont), which permits possession/use only, while the other states permit both sales and use.

Drug and Social Policies

Table 2 compares drug and social policies among nonlegal, early-adopter medical, late-adopter medical, and recreational marijuana states. States with legal medical and recreational marijuana are also more likely to have decriminalized marijuana compared with nonlegal states (57–100% vs. 18%, p ≤ .02). States in all categories of marijuana legalization also are less likely to have a ban on off-premises sales of alcohol on Sundays compared with nonlegal states (0–10% vs. 41%, p ≤ .051). However, there was no significant difference in the shares of states with alcohol sales tax controls.

State Social and Drug Policies by Marijuana Legalization Status (Percentages and Medians).

State sets the price of and gains profit/revenue directly (rather than solely from taxation) from the wholesale or retail system of distribution for the index beverage.

Bans on Off-Premises Sunday Sales—States are classified as having local option if at least some local governments have the authority to permit Sunday sales as an exception to a State ban.

Residents of states in which medical or recreational marijuana is legal were more likely to approve of gay marriage than residents in nonlegal states (55–61% vs. 44%, p ≤ .015). Early-adopter medical and legal marijuana states are more likely than nonlegal states to allow nurse practitioners to practice without physician oversight (73–85% vs. 24%, p ≤ .019), but this difference is not apparent for late-adopter medical states (33%, p = .721).

There are notable differences in abortion policy between early-adopter medical and recreational marijuana states as compared with late-adopter medical and nonlegal states. Approximately three quarters of early adopter medical and recreational states protect or strongly protect abortion access, while less than one third of late-adopter medical states and no nonlegal states protect abortion access ( p ≤ .005). Abortion access is severely restricted in 94% of nonlegal marijuana states and 52% of late-adopter medical marijuana states. In contrast, there are no significant differences across state categories regarding stand-your-ground or concealed-carry gun laws, although a lower share of all categories of legal marijuana states have stand-your-ground gun laws (27–38%) as compared with nonlegal marijuana states (65%, p ≥ .12). Legal marijuana states also have a higher share of states with limited issue of concealed-carry permits (18–24% vs. 0%), but the overall differences are not statistically significant ( p ≥ .076).

Figure 2 shows geographic patterns regarding marijuana legalization, support for gay marriage, laws allowing nurse practitioners to practice without physician oversight, and “stand-your-ground” gun laws. The associations described in Table 2 are apparent in these maps. The same geographic regions that have been resistant to liberalized marijuana policies—southeastern and south central states—also are less likely to support gay marriage or allow nurse practitioners to practice without physician oversight. More complex relationships are apparent between states with stand-your-ground gun laws and those that have liberalized marijuana policy. All western states with stand-your-ground laws permit medical marijuana (Arizona, Montana, Utah) or recreational marijuana (Nevada). Among the five south central and southeastern states with medical marijuana laws (Arkansas, Florida, Louisiana, Oklahoma, West Virginia), all but one (Arkansas) have stand-your-ground gun laws; most other states in these regions have stand-your-ground gun laws but have resisted medical marijuana and none have legalized recreational marijuana. Michigan and New Hampshire are the only two other states with both stand-your-ground and medical marijuana laws.

In the U.S., passage of restrictive marijuana control policies commenced in the early 20th century with a movement across states that culminated in a federal policy prohibiting all cultivation, sales, and use ( Siff, 2014 ). Over the past 20 years, we have witnessed a dismantling of marijuana control policies in a similar movement across states. This study investigated the underlying social and political factors that may influence marijuana policy liberalization.

We observed that the passage of more permissive marijuana policies follows a clear geographic pattern. In all cases—decriminalization, medical marijuana, and recreational use laws—the pattern began in western states. Once western states initiated adoption of a less restrictive marijuana policy, the pattern of diffusion “jumped coasts” to the northeast, reaching states that share similar (but less pronounced) social and political characteristics. After a critical mass of these states passed the given marijuana policy, the trend moved toward states in the northern central and mid-Atlantic regions. There has been little movement toward liberal marijuana policy in the Southeastern and Central regions. This geo-temporal pattern has been observed in the diffusion of decriminalization and medical marijuana laws and appears to be in its early stages for laws permitting adult recreational use.

We found clear patterns in the social and political characteristics of states participating in the recent wave of marijuana policy liberalization, characterized by large immigrant populations and low rates of goods production, Evangelical Protestantism, religious observance, and political conservatism. States that have resisted liberalization, which are generally located in the Southeastern and Central regions, tend toward Evangelical Protestantism and strong religious observance, disproportionately low representations of Asians and immigrants, and high shares of workers in goods-producing occupations. The associations measured in our analysis do not demonstrate causal relationships and, for some variables such as goods production, may reflect other geographically correlated social patterns. Other associations, such as religiosity, are more likely to directly explain marijuana policy trends. Religion has had an important influence in American alcohol and other drug policy, with Evangelicalism playing a large role in the U.S. temperance and prohibition movements ( Schmidt, 1995 ).

The political environment, including whether citizens can place initiatives and referenda on the ballot, is also associated with the establishment of liberal marijuana policies. The states that first allowed medical marijuana often did so by initiative or referendum, which likely reflected the difference between established policy and public perceptions of marijuana. The option for citizens to propose initiatives and referenda also aligns with libertarian views of government regulation and policy change, which may extend to drug policy.

In recent years, legislative passage of medical marijuana has become more common than ballot initiatives. There also has been a notable shift in toward medical marijuana passage in states in which Republicans controlled the state legislature in 2014. National advocacy organizations, including the Marijuana Policy Project (MPP), National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws (NORML), and Drug Policy Alliance, have provided financial and logistical support to campaigns for liberal marijuana policies through both legislation and initiatives/referenda. Through 2014, political donations by MPP were directed primarily at Democrats. However, since 2016, a greater share of their donations has gone to Republican candidates ( OpenSecrets.org, 2018 ). These organizations and new advocacy groups, such as the New Federalism Fund and the National Cannabis Industry Association, are increasingly funded by the marijuana industry ( Hughes, 2018 ; Wallace, 2017 ). In early 2018, the value of the marijuana industry was estimated at $8 billion, generating at least $2 billion in taxes ( Hughes, 2018 ), increasing the financial incentive to lawmakers to adopt permissive policies.

Comparisons of marijuana laws and other drug and social policies found positive correlations: The divide between states on marijuana policy is mirrored in political divisions over widening the scope of nurse practitioner practice, gun control, and gay marriage. However, we observed some notable exceptions. Some western states that have legalized recreational use depart from the pattern by opposing gun control. This could be accounted for by the different political configurations in more libertarian western states, where personal freedoms are highly valued, including both freedoms to own guns and use marijuana. At the same time, traditionally conservative southeastern states have higher shares of Evangelical Protestants who attend religious services regularly, and these states are also prone to restrict nurse practitioner practice and disapprove of gay marriage.

Galston and Dionne (2013) examined a number of social policies in relation to support for marijuana legalization and highlighted key factors that are apparent in our analysis. First, although Democrats are more likely to support legalization of marijuana than Republicans, a growing share of Republicans also support legalization or at least do not actively support criminalization. This appears to be associated with skepticism about whether enforcing marijuana laws produces a net social benefit, as well as libertarian leanings among some Republicans. Galston and Dionne also note that divisions in views of social policies across age groups may be predictive of long-term changes. For example, views of gay marriage are correlated with age, with younger people strongly in support, portending a trend toward widespread support of gay marriage. In contrast, views of abortion are not associated with age, suggesting ongoing conflict, and states with restrictive abortion policies also strongly lean toward restrictive marijuana policies. However, public option of marijuana legalization is more positive among younger people than older people, which increases the potential for national liberalization of marijuana policy over time.

Each state’s medical marijuana law is different, with variation in provisions such as whether patients must register with the state, whether caregivers can purchase marijuana for patients, how much marijuana a patient can possess, and whether patients can grow their own plants. Previous research has categorized state laws through 2014 according to how easy it is to become an approved medical marijuana user, the quantity of marijuana that can be possessed, and the degree of state control over marijuana distribution ( Chapman, Spetz, Lin, Chan, & Schmidt, 2016 ). States that passed medical marijuana laws prior to 2010 permit possession of larger quantities, make it easier to be approved as a medical marijuana user, and have less-controlled distribution systems than states that passed laws from 2010 through 2014. In other words, late adopters of medical marijuana have established more conservative and controlled programs than early adopters.

In the past three years, five southeastern states passed medical marijuana laws, suggesting a shift toward approval of medical marijuana even in states that have historically resisted it. President Trump won the vote by wide margins in these states and his administration has indicated support for medical marijuana ( Halper, 2018 ). National polls show increasingly widespread support for the use of marijuana if prescribed by a physician ( Bogdanoski, 2010 ) and, in 2016, 57% of adults favored recreational legalization ( Anderson & Olmstead, 2016 ). National policy also is shifting; the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved a marijuana-derived pharmaceutical for the treatment of epilepsy in 2018 ( Joseph, 2018 ) and bipartisan federal legislation would remove marijuana from the Drug Enforcement Agency Schedule 1 category, which is for drugs that have no accepted medical use and a high potential for abuse ( Halper, 2018 ). MPP has spent more than $1 million in federal lobbying since 2002, and the Drug Policy Alliance, which seeks reform of all drug laws, has spent almost $4.2 million in federal lobbying since 2001. Nonetheless, medical marijuana legislation proposed in most states that do not yet permit it did not fare well in 2018, demonstrating ongoing resistance to marijuana legalization.

Limitations

This study has two important limitations. First, the analysis is correlational and is not designed to precisely define the complex processes that underlie marijuana policy change. The demographic, economic, political, and social characteristics and policies examined were measured at only one point in time, even though many of the characteristics are time-varying. Thus, the variables were not measured for the years when most states passed their medical or recreational marijuana laws. We examined whether the patterns described in this paper changed if different years of data were used for a few variables, such as unemployment rates in 2004 and 2016, and obtained similar results. However, because the relationships described are asynchronous, the analysis cannot be viewed as predictive or causal with respect to marijuana policies.

Second, patterns in marijuana policy adoption are almost certainly driven by more complex factors than those discussed here. The interplay of social norms, political structure, legislative and ballot initiative strategy, and advocacy cannot be readily disentangled. Nonetheless, we found some patterns both across states and over time that suggest that some demographic, economic, and political characteristics may be more important than others.

This study was an initial effort to understand patterns of marijuana liberalization across diverse U.S. states. Future research should examine international variation in geo-temporal patterns, as well as in the underlying social and political configurations observed here, which may be applicable to other societies. There is a further need for systematic studies on the characteristics of new marijuana policies ( Chapman et al., 2016 ), which may reflect subtle differences in social, demographic, and economic characteristics ( Gass, 2016 ; Kilmer & Pacula, 2017 ). Differences in the ways liberalization policies regulate marijuana may be critical for mitigating public health harms, such as youth marijuana use and secondhand smoke exposure.

The trend toward marijuana policy liberalization, in the U.S. and worldwide, raises concerns about the current scarcity of research on the medical value of marijuana and its public health impacts ( Hajizadeh, 2016 ; Lake & Kerr, 2017 ). Research to date suggests that marijuana use is accompanied by a range of harms ( Feeney & Kampman, 2016 ; Volkow et al., 2014 ), although advocates for legalization argue that marijuana is already widely available through illicit markets, leaving governments unable to regulate its potency and distribution ( Nathan, Clark, & Elders, 2017 ; Williams, 2016 ), prevent youth exposure ( Spithoff & Kahan, 2014 ; Ubelacker, 2014 ), and consider the benefits of making marijuana available as an alternative to riskier substances ( Lau et al., 2015 ; Lucas et al., 2013 , 2015 ; Vyas, LeBaron, & Gilson, 2017 ). Evidence presented here suggests that, because the liberalization of marijuana policy is likely to continue, there is a global need to build up the evidence base on marijuana and health, the public health consequences of rolling back marijuana controls, and strategies for regulating access in a legalization context.

Acknowledgments

The assistance of Jessica Lin and Krista Chan in collecting state-level data is appreciated. Juliana Fung helped to develop graphics for the figures.

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by a grant from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01 DA034091–01).

Author Biographies

Joanne Spetz , PhD, is a professor at the Philip R. Lee Institute for Health Policy Studies and the Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of California, San Francisco. She also is Associate Director for Research at Healthforce Center at University of California, San Francisco.