Home — Essay Samples — History — Civil Rights Movement — How Did Martin Luther King Change the World?

How Did Martin Luther King Change The World?

- Categories: Civil Rights Movement

About this sample

Words: 459 |

Published: Mar 5, 2024

Words: 459 | Page: 1 | 3 min read

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Dr Jacklynne

Verified writer

- Expert in: History

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

2 pages / 1077 words

3 pages / 1141 words

3 pages / 1293 words

3 pages / 1536 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Civil Rights Movement

The Black Panther Party, originally the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense, was a revolutionary socialist organization founded in the United States in 1966. The party's primary objectives were to challenge police brutality and [...]

As one of the most influential and powerful nations in the world, the question of whether America still exists is a thought-provoking and complex topic. With its rich history, diverse population, and global impact, America has [...]

Madame Haupt is a significant character in the novel "Les Misérables" by Victor Hugo. Her role in the story is complex, and her actions and decisions have a profound impact on the lives of other characters. This essay will [...]

In the history of the United States, two prominent figures, Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X, have played pivotal roles in the fight for civil rights and equality. While both leaders had different approaches and ideologies, [...]

Civil rights are formed by a nation or a state, are legally binding and enforced by those nations and states. Civil rights vouch for essentially equality, the belief that an individual can participate in the civil life of a [...]

Civil rights activist Rosa Parks (February 4, 1913 to October 24, 2005) refused to surrender her seat to a white passenger on a segregated Montgomery, Alabama bus, which spurred on the 381-day Montgomery Bus Boycott that helped [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

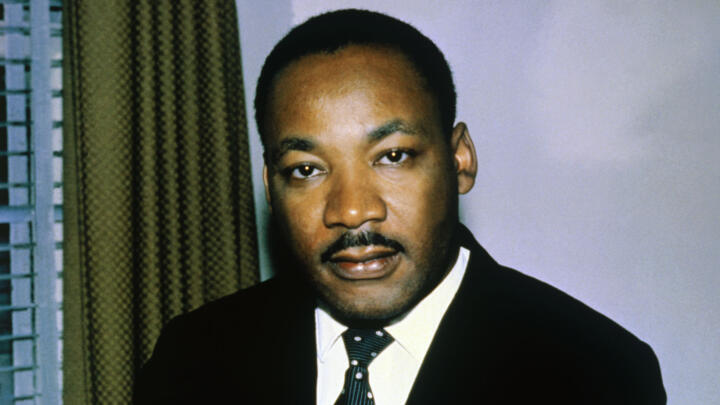

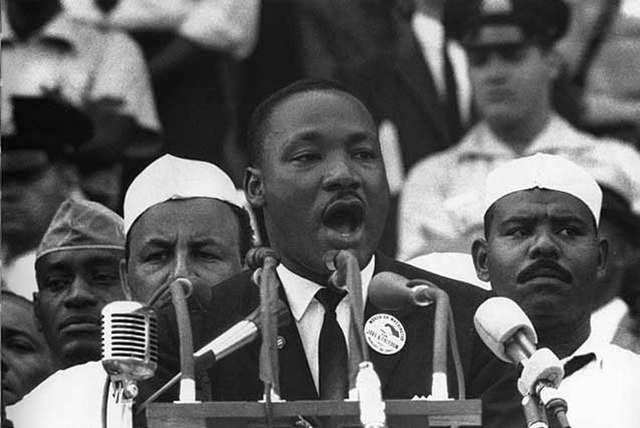

Examining The Global Impact Of Martin Luther King Jr.

On Martin Luther King Jr. Day, Americans pay tribute to the iconic leader renowned for his role in the U.S. civil rights movement. What some may not know is that King’s influence and legacy extended beyond the U.S.; he visited countries in West Africa, toured Europe and South America, and spent a month in India where it is said he was inspired by Mahatma Gandhi’s use of nonviolence in protests against British rule.

Texas A&M Today spoke with Professor of History Dr. Albert S. Broussard about King’s global impact. Broussard specializes in African-American history and is the author of books and other publications on topics including slavery, civil rights and racial equality.

What are some of the ways King carried his humanitarian message to the world?

Martin Luther King, Jr. is regarded today as one of the most significant leaders in world history. Although he is widely regarded as one of the most important civil rights leaders in U.S. history, Dr. King began to speak out on other pressing global issues following receipt of the Nobel Peace Prize in 1964.

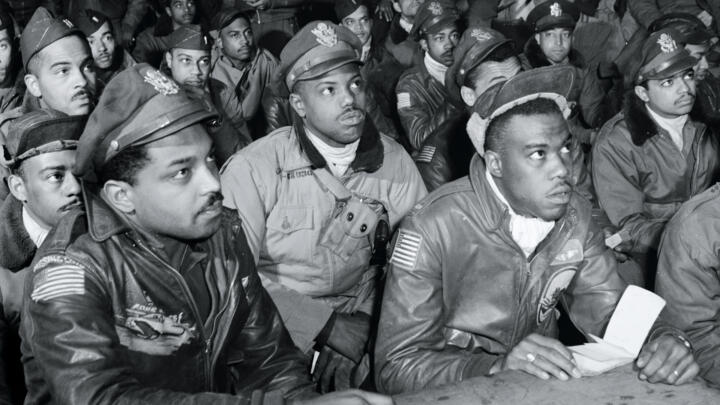

King, himself, felt that the award imposed a responsibility to address issues larger than civil rights, and he felt that receiving an international award also gave him the gravitas to offer his views. Few people know that King, for example, spoke out against the racist apartheid regime in South Africa, which collapsed in 1991. Had he lived, there is no doubt that King and Nelson Mandela, South Africa’s first Black president, would have become kindred spirits. King also spoke out against nuclear war and regarded himself as an anti-nuclear war activist, condemning the use of nuclear weapons against Japan during World War II. Finally, Dr. King was a major critic of the Vietnam War, and his criticism of the war and the role that the U.S. played drew widespread condemnation against the United States and fueled the anti-war movement in America.

Why do you think it was important to King to have a place on the global stage?

King, like many global activists, believed that he had an obligation to speak out against global issues in part because of his celebrity. But, as a Christian minister, he also believed that Jesus had spoken to him directly from the time of his first civil rights campaign in Montgomery, Alabama, in 1955. To put this another way, Dr. King believed that he was doing God’s work.

What is your favorite King quote as it relates to spreading his message worldwide?

The quote that I always recall by Dr. King that can be used to support both national and international reform is, “The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice.” According to Clayborne Carson, editor of the Martin Luther King, Jr. Papers Project at Stanford University, this quote has been attributed to Theodore Parker, a 19th century abolitionist and Unitarian.

How is his message still relevant today?

I think leaders like Dr. King provide hope, even in the darkest moments of a nation’s history, that change is possible if people are willing to struggle and make sacrifices. As the great 19th century Black abolitionist Frederick Douglass wrote, “Power concedes nothing without a demand.” Dr. King certainly understood that sentiment as well as thousands of ordinary people and activists around the world today fighting to improve their lives and to guarantee a better future for their families.

Related Stories

Department Of Philosophy Announces New Major

The state-approved Society, Ethics and Law major is for students interested in professions such as law, fundraising and community service.

Aggie Special Agent Protects Team USA Judo At Paris Olympics

Caleb Lenard '13 said his involvement in programs and organizations as a student at Texas A&M helped him land a highly competitive job.

Texas A&M’s Quest To Save An Alamo Cannon

A team of anthropologists developed an acid solution to remove a mysterious substance growing on the 18th century bronze cannon.

Recent Stories

Department of Economics Receives $1 Million Endowment From Former Student

The gift from Luke Soules ’61 will support future professors in the department whose work focuses on global macroeconomics theory and policy.

Drinking Alcohol Before Conceiving A Child Could Accelerate Their Aging

Texas A&M research shows parents' chronic alcohol use has an enduring effect on the next generation.

From Turfgrass To Touchdowns

Go behind the scenes to see how Aggie turfgrass science students keep Kyle Field game day ready.

Subscribe to the Texas A&M Today newsletter for the latest news and stories every week.

Loading to How Did Martin Luther King Change History....

Martin Luther King Essay for Students and Children

500+ words essay on martin luter king.

Martin Luther King Jr. was an African-American leader in the U.S. He lost his life while performing a peaceful protest for the betterment of blacks in America. His real name was Michael King Jr. He completed his studies and attained a Ph.D. After that, he joined the American Civil Right Movement. He was among one of the great men who dedicated their life for the community.

Reason for Martin Luther King to be famous

There are two reasons for someone to be famous either he is a good man or a very bad person. Martin Luther King was among the good one who dedicated his life to the community. Martin Luther King was also known as MLK Jr. He gained popularity after he became the leader and spokesperson of the Civil Rights Movement in the 1950s and 1960s.

Martin Luther King was an American activist, minister, and humanitarian. Also, he had worked for several other causes and actively participated in many protests and boycotts. He was a peaceful man that has faith in Christian beliefs and non-violence. Also, his inspiration for them was the work of Mahatma Gandhi and Nelson Mandela. For his work in the field of civil rights, the Nobel Committee awarded him the Nobel Peace Prize.

He was a great speaker that motivated the blacks to protest using non-violence. Also, he uses peaceful strategies like a boycott, protest march , and sit-ins, etc. for protests against the government.

Impact of King

King is one of the renowned leaders of the African-American who worked for the welfare of his community throughout his life. He was very famous among the community and is the strongest voice of the community. King and his fellow companies and peaceful protesters forced the government several times to bend their laws. Also, kings’ life made a seismic impact on life and thinking of the blacks. He was among one of the great leaders of the era.

Get the huge list of more than 500 Essay Topics and Ideas

Humanitarian and civil rights work

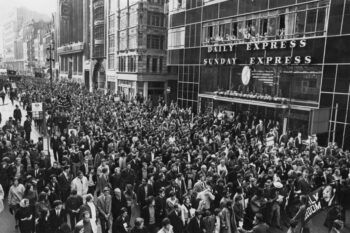

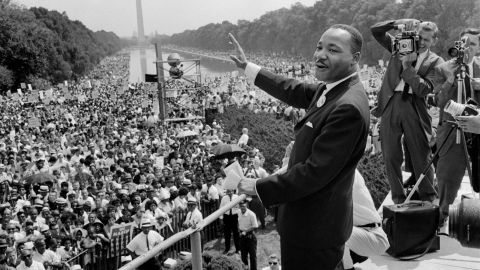

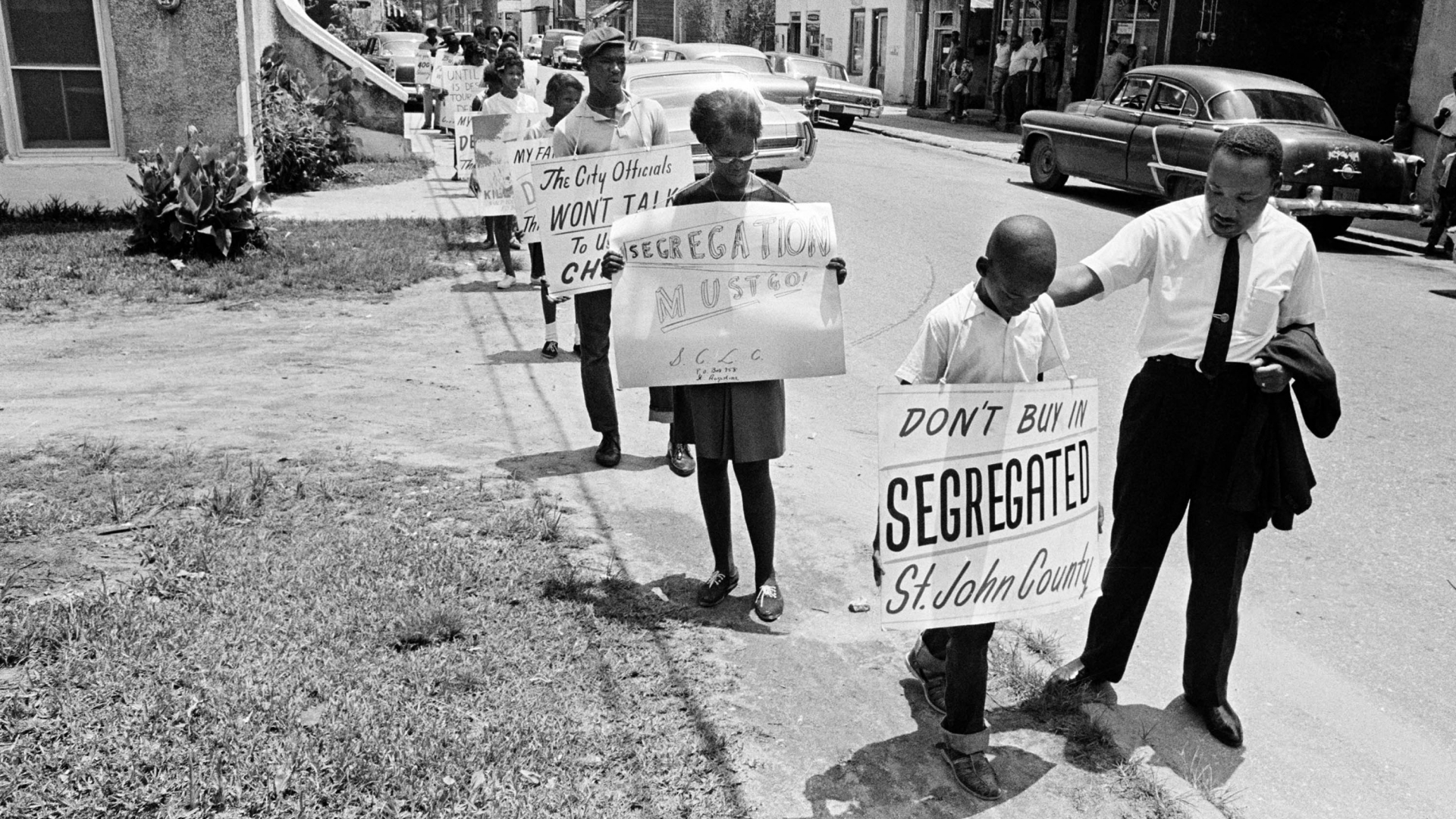

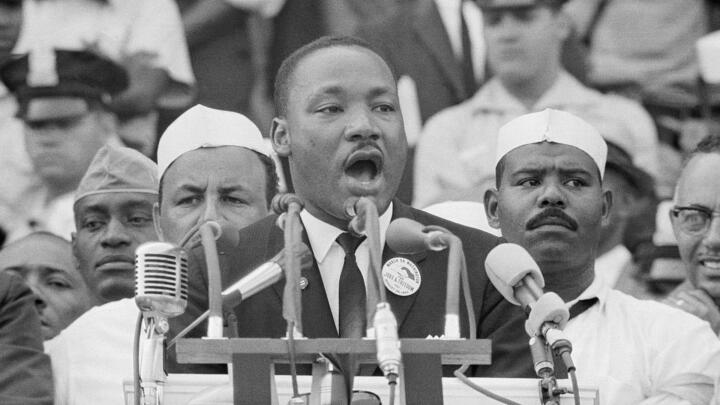

As we know that King was a civic leader . Also, he has taken part in many civil right campaigns and boycotts like the Bus Boycott, Voting Rights and the most famous March on Washington. In this march along with more than 200,000 people, he marched towards Washington for human right. Also, it’s the largest human right campaign in U.S.A. history. During the protest, he gave a speech named “I Have a Dream” which is history’s one of the renowned speeches.

Death and memorial

During his life working as a leader of the Civil Rights Movement he makes many enemies. Also, the government and plans do everything to hurt his reputation. Martin Luther King was assassinated in 1968. Every year the US celebrates his anniversary as Martin Luther King Jr. day in the US. Also, they honored kings’ memory by naming school and building after him and a Memorial at Independence Mall.

Martin Luther King was a great man who dedicated his whole life for his community. Also, he was an active leader and a great spokesperson that not only served his people but also humanity. It was due to his contribution that the African-American got their civil rights.

Essay Topics on Famous Leaders

- Mahatma Gandhi

- APJ Abdul Kalam

- Jawaharlal Nehru

- Swami Vivekananda

- Mother Teresa

- Rabindranath Tagore

- Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel

- Subhash Chandra Bose

- Abraham Lincoln

- Martin Luther King

Customize your course in 30 seconds

Which class are you in.

- Travelling Essay

- Picnic Essay

- Our Country Essay

- My Parents Essay

- Essay on Favourite Personality

- Essay on Memorable Day of My Life

- Essay on Knowledge is Power

- Essay on Gurpurab

- Essay on My Favourite Season

- Essay on Types of Sports

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Download the App

- HISTORY & CULTURE

- RACE IN AMERICA

How Martin Luther King, Jr.’s multifaceted view on human rights still inspires today

The legendary civil rights activist pushed to ban nuclear weapons, end the Vietnam War, and lift people out of poverty through labor unions and access to healthcare.

The Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr. towers over history as a civil rights legend—known for leading the movement to end segregation and counter prejudice against Black Americans in the 1950s and 1960s, largely through peaceful protests. He helped pass landmark federal civil rights and voting rights legislation that outlawed segregation and enfranchised Americans who had been barred from the polls through intimidation and discriminatory state and local laws.

( How the Voting Rights Act was won—and why it’s under fire today .)

But King knew it would take more to achieve true equality. And so he also worked tirelessly for education, wage equity, peace, housing, and to lift people out of poverty. Some of King’s most iconic speeches and marches were devoted to ending war, dismantling nuclear weapons, and bringing economic justice. As King said after receiving the Nobel Peace Prize in 1964 , he believed that any “spiritual and moral lag” in humanity was due to racial injustice, poverty, and war.

His multifaceted view on human rights still inspires today, and on the third Monday in January every year, the United States honors King’s legacy of fighting for equal rights—and standing up for human rights everywhere.

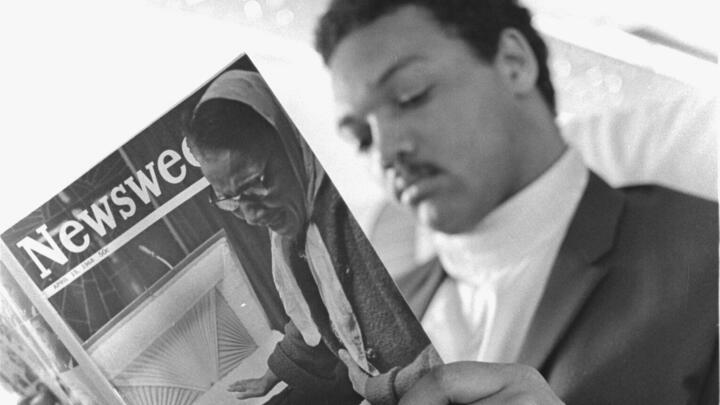

During his lifetime, King’s views often made him unpopular and heralded harsh criticism. At the time of his assassination in 1968, a Harris poll revealed a low approval rating of only about 25 percent among white Americans and 52 percent among Black Americans. But in the decades after he was killed, more Americans came to recognize the enormity of King’s contributions. Communities across the country began to name streets and landmarks after him, and soon a push began to establish a federal holiday in his birth month of January.

( Subscriber exclusive: Where the streets have MLK’s name .)

In 1983 , over objections from Southern lawmakers, President Ronald Reagan finally signed a bill creating the holiday into law and the first celebrations of Martin Luther King, Jr. Day took place in January 1986—although it would take another decade for states such as Arizona and South Carolina to follow suit.

King’s work continues to influence and inspire activism—particularly in the realm of environmental justice, as studies indicate that climate change disproportionately harms marginalized communities. Here are the many layers of King’s work that the U.S. honors on Martin Luther King, Jr. Day.

He advocated against the use of nuclear weapons

King was adamant that peace was inextricably linked to civil rights. Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, major powers like the United States and the U.S.S.R. were aggressively developing and testing nuclear weapons, and several times crept to the brink of warfare that threatened to annihilate the world.

King made clear the connection between the Black freedom struggle and the need for nuclear disarmament, writes nuclear studies and African American history expert Vincent Intondi in the book African Americans Against the Bomb: Nuclear Weapons, Colonialism, and the Black Freedom Movement . King argued that it would be “rather absurd” to integrate schools and lunch counters but not be concerned with world peace and survival.

King spoke out about nuclear warfare as early as 1957, when he signed onto a full-page advertisement in The New York Times that called for all nations to suspend nuclear tests immediately. When asked about his stance later that same year, King tied the weapons to the whole of war, and argued that they should be banned everywhere.

“It cannot be disputed that a full-scale nuclear war would be utterly catastrophic,” he told Ebony magazine in an interview. “The principal objective of all nations must be the total abolition of war.”

As part of King’s advocacy for peace and nuclear disarmament, he condemned the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki the U.S. government had carried out more than a decade earlier to effectively end World War II. Today, Hiroshima is one of the only cities outside North America to celebrate Martin Luther King Day.

King also used the Cuban Missile Crisis in October 1962—a 13-day stretch in which the U.S. and Soviet Union stood on the brink of nuclear war over the discovery of Soviet missiles in Cuba—as an opportunity to connect nuclear disarmament to racial and economic justice. King called for the U.S. government to instead turn its attention and funds to education, Medicare, and civil rights, Intondi writes. He then voiced his support for a nuclear test ban treaty , which was signed by President John F. Kennedy in 1963.

He was outspoken against the Vietnam War

King often linked nuclear disarmament with the Vietnam War as it escalated in the 1960s.

King was against the war but initially worried that making his stance public would derail his work to pass the Civil Rights Act and impair his relationship with President Lyndon B. Johnson, according to the Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Education Institute at Stanford University .

But in 1965, the year the first U.S. ground troops were sent to Vietnam, King issued his first public statement, asserting the war was “accomplishing nothing” and calling for a peace treaty.

He tempered his criticism for the next two years to avoid diminishing the impact of his civil rights work, but by 1967, King was active in the anti-war sphere again, attending a march in Chicago before he went on to make his most notable speech on the matter a few days later on April 4.

It is no longer a choice, my friends, between violence and nonviolence. It is either nonviolence or nonexistence. And the alternative to disarmament… may well be a civilization plunged into the abyss of annihilation , and our earthly habitat would be transformed into an inferno that even the mind of Dante could not imagine. Martin Luther King, Jr.

On that day at the Riverside Church in New York City, King denounced the war for deepening the problems of Black Americans and people living in poverty. He condemned the “madness” of Vietnam as a “symptom of a far deeper malady” that put the U.S. at odds with the aspirations for social justice throughout the world. Just 11 days later, King led 125,000 demonstrators on an anti-war march to the United Nations headquarters in New York as one of the largest peace demonstrations in history.

You May Also Like

The perfect storm that led to the Jonestown massacre

Harriet Tubman, the spy: uncovering her secret Civil War missions

MLK and Malcolm X only met once. Here’s the story behind an iconic image.

During the last year of his life , King continued his anti-war work by encouraging grassroots peace activism. On March 31, 1968, five days before he died, King denounced the Vietnam War in his final Sunday sermon at the National Cathedral in Washington, D.C., saying that it was “one of the most unjust wars that has ever been fought in the history of the world.”

King did not live to see the war end. U.S. troops officially pulled out of Vietnam in April 1975 .

He championed union representation and worker’s rights

King's passion for union representation and workers' rights is also an important part of his legacy. Much as he had done with his anti-war speeches, King often tied workers’ rights to the civil rights movement.

“I had also learned that the inseparable twin of racial injustice was economic injustice,” King said in a 1958 speech in New York . “Although I came from a home of economic security and relative comfort, I could never get out of my mind the economic insecurity of many of my playmates and the tragic poverty of those living around me.”

In a 1959 interview with Challenge magazine , King acknowledged that labor unions had historically left out Black Americans, but also could be a key to economic justice. He called for Black Americans to organize their economic and political power in the form of labor unions, and he championed ideas in the labor movement, including better working conditions, adequate housing, guaranteed annual income, and access to healthcare.

For years, King continued to call for economic justice, notably at the August 28, 1963, March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. Before a crowd of 250,000 people, he delivered the legendary “I Have A Dream” speech on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial, where he called for an end to poverty, especially targeted poverty and discrimination against Black Americans.

One of King’s last actions before his assassination was in support of the labor movement. King’s final days were spent supporting a group of Black sanitation workers striking in Memphis, Tennessee.

After two workers had been crushed to death by a malfunctioning truck, 1,300 Black workers went on strike for 11 days, seeking an end to a long pattern of neglect and abuse from their management. The strike would’ve ended after the City Council voted to recognize their newly formed union, but the Memphis mayor rejected the vote. King traveled to Memphis to lead a protest march and, on April 3, he spoke to the striking sanitation workers.

“We’ve got to give ourselves to this struggle until the end,” King said . “Nothing would be more tragic than to stop at this point in Memphis. We’ve got to see it through.”

King was gunned down by an assassin on the balcony of his Memphis hotel the next day. On April 16, the sanitation workers’ union was finally recognized and a better wage was promised—the first of many examples of how King’s legacy would continue to reverberate in the work of those whom he inspired.

I have the audacity to believe that peoples everywhere can have three meals a day for their bodies, education and culture for their minds, and dignity, equality and freedom for their spirits. Martin Luther King, Jr.

He’s inspiring a new generation of environmental activists

Although King’s last act supporting the Black sanitation workers in Memphis was not explicitly an act of environmental justice , it has inspired a generation of activists. The working conditions the sanitation workers had endured were polluted and hazardous—much like the conditions many Black Americans endured in their communities and jobs at the time.

Modern environmental activists have drawn on King’s message: Much as segregation and discrimination were inseparable from poverty, they point out that poor communities of color disproportionately face environmental hazards such as pollution. They also bear the brunt of the harmful effects of climate change, including extreme weather events.

( The origins of environmental justice—and why it’s finally getting the attention it deserves .)

Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which prohibits discrimination in the use of federal funds , even gave marginalized people a means to address racial discrimination in environmental matters. As the environmental justice movement grew, King’s work also inspired the Clean Air Act, the Clean Water Act, and the Endangered Species Act.

His advocacy for people of color to have a voice and power has inspired many communities impacted most by climate change to speak up—and take action. Now, the holiday honoring King is typically observed as a national day of service. Organizations and individuals alike volunteer for their communities, often cleaning up roads or river banks in the name of a man who many believe would be on the forefront of the climate fight if he were still alive today.

Related Topics

- CIVIL RIGHTS

- HUMAN RIGHTS

- ENVIRONMENTAL JUSTICE

- NUCLEAR WEAPONS

- VIETNAM WAR

Why Aboriginal Australians are still fighting for recognition

Meet the mom who took on toxic waste—and won

This is what you need to know about lead and your health

The surprising way that millions of new trees could transform America

How César Chávez changed the labor movement—and became an icon

- Environment

- Paid Content

History & Culture

- History & Culture

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Your US State Privacy Rights

- Children's Online Privacy Policy

- Interest-Based Ads

- About Nielsen Measurement

- Do Not Sell or Share My Personal Information

- Nat Geo Home

- Attend a Live Event

- Book a Trip

- Inspire Your Kids

- Shop Nat Geo

- Visit the D.C. Museum

- Learn About Our Impact

- Support Our Mission

- Advertise With Us

- Customer Service

- Renew Subscription

- Manage Your Subscription

- Work at Nat Geo

- Sign Up for Our Newsletters

- Contribute to Protect the Planet

Copyright © 1996-2015 National Geographic Society Copyright © 2015-2024 National Geographic Partners, LLC. All rights reserved

How Did Martin Luther King Changed The World Essay

Martin Luther King Jr.’s vision changed the world by empowering African Americans to fight for their rights through nonviolent civil disobedience. Martin Luther King’s “I Have a Dream” speech is widely considered one of the greatest speeches in American history. In it, he called for an end to racial segregation and discrimination. His words inspired millions of black Americans to stand up for their rights, culminating in the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

These laws outlawed discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex, or national origin. They also guaranteed African Americans the right to vote. Martin Luther King’s vision changed America for the better and ensured that everyone is treated equally regardless of skin color.

Most of us have dreams, but Martin Luther King Jr. had a dream that surpassed most and changed the course of history for African American people. Martin Luther King Jr. was one of the most prominent African American civil rights leaders during his time. Under his leadership, many important advances were made for equality and justice.

His work towards equality and civil disobedience continues to influence people today. Martin Luther King Jr’s dream was to see the African American people gain equal rights to the white people. Sadly, he was assassinated before he could see his dream come true. However, his vision did change the world in many ways.

Martin Luther King Jr.’s famous “I Have a Dream” speech called for an end to discrimination and violence against African Americans. His words inspired many people, both black and white, to work together for change. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 outlawing segregation in public places and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 giving African Americans the right to vote are just two examples of how Martin Luther King’s vision changed the world.

Today, Martin Luther King’s dream of equality is still being fought for. Although there has been much progress made, there is still more work to be done. Martin Luther King’s vision continues to inspire people all over the world to stand up for what they believe in and fight for change.

Martin Luther King Jr. was an important leader of the civil rights movement who worked hard to change America’s laws and improve the situation for African Americans. He always used peaceful methods in his protests against discrimination, which made him very respected by many people.

Martin Luther King’s vision changed the world by helping to end segregation and racism in America, as well as promoting non-violent protests as a way to achieve change.

Martin Luther King Jr. was born in Atlanta, Georgia on January 15, 1929. He was an African American Baptist minister and activist who is most well-known for his role in the civil rights movement. Martin Luther King received his Ph.D. in systematic theology from Boston University in 1955. In 1963, Martin Luther King organized and led the March on Washington, where he delivered his famous “I Have a Dream” speech advocating for racial harmony.

King’s work towards social change began long before the March on Washington though. In December of 1955, Martin Luther King led the Montgomery Bus Boycott to protest segregation on public buses in Alabama. The boycott lasted 381 days and resulted in a U.S. Supreme Court ruling that declared segregated buses unconstitutional.

In 1957, Martin Luther King helped found the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), an organization devoted to peaceful protests for civil rights reform. Under Martin Luther King’s leadership, the SCLC organized multiple campaigns against segregation and racism, including the famous Birmingham Campaign of 1963.

The Birmingham Campaign was a series of nonviolent protests in Birmingham, Alabama that took place between April and May of 1963. The campaign was organized by Martin Luther King and the SCLC in order to draw attention to the injustices faced by African Americans in Birmingham, such as police brutality and racial segregation in public places. The campaign ended with the arrest of over 2,000 people, including Martin Luther King.

While he was in jail, Martin Luther King wrote his famous “Letter from Birmingham Jail” in which he argued that individuals have a moral responsibility to disobey unjust laws. The letter became one of the most important documents of the civil rights movement and helped Martin Luther King gain support for his cause.

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., is unquestionably the most famous and accomplished activist in history. Dr. Martin Luther King, Junior, as he was originally known, lived for only thirty-nine years on this Earth. He had one of the biggest influences on African-American rights and America itself during his thirty-nine years on earth.

Lower social status groups were treated unfairly during 1954-1968, radiating frustration, racism, hunger and violence throughout the entire society. Martin Luther King Jr., an outstanding hero who used to be a priest, helped African Americans and poor people gain basic human rights after the Civil War. Although he only lived for thirty nine years old, he was deeply influenced by Christianity and allusive of the Bible in both his notion speeches.

Martin Luther King believed that people should not be judged by the color of their skin but by their character, which is also one of the principles in Christianity.

He fought for what he thought was right and changed American society—African-Americans could now get an education, have a job, and vote. Martin Luther King’s speeches were often quoted “I Have a Dream” which is his most famous speech delivered on August 28th, 1963, at the Lincoln Memorial during the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom.

In this speech, Martin Luther King Jr. used rhetoric to appeal to both emotion and logic, making it an incredibly effective speech that helped galvanize the Civil Rights Movement. By using personal stories and images, he was able to tap into the hearts of his audience and get them to see the world through his eyes.

Martin Luther King’s vision for America was one where all people would be treated equally, regardless of race or gender. This dream has largely been realized in America today, although there is still room for improvement. Thanks to Martin Luther King Jr., we are now closer to achieving true equality in America than ever before. His vision changed the world and continues to inspire people to fight for what they believe in.

Martin Luther King Jr. is a role model for many people because he fought for what he thought was right, even though it was not the popular opinion at the time. He showed that change is possible if enough people come together and stand up for what they believe in. Martin Luther King’s vision for America is one that is still relevant today, and his legacy will continue to inspire people for generations to come.

More Essays

- Did Martin Luther King Jr Dream Come True

- Gandhi And Martin Luther King Similarities

- Martin Luther King Reflection Essay

- Similarities Between Martin Luther King And Mahatma Gandhi Essay

- Martin Luther King and Malcom X

- Rhetorical Analysis Of Dr. Martin Luther King’s Letter From Birmingham Jail Essay

- Summary Of I Have A Dream Speech Essay

- Rhetorical Strategies In Letter From Birmingham Jail Essay

- King Jr Human Rights Essay

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

24/7 writing help on your phone

To install StudyMoose App tap and then “Add to Home Screen”

How Did Martin Luther King's Vision Change the World?

Save to my list

Remove from my list

Works Cited

How Did Martin Luther King's Vision Change the World?. (2020, Sep 13). Retrieved from https://studymoose.com/how-did-martin-luther-kings-vision-change-the-world-essay

"How Did Martin Luther King's Vision Change the World?." StudyMoose , 13 Sep 2020, https://studymoose.com/how-did-martin-luther-kings-vision-change-the-world-essay

StudyMoose. (2020). How Did Martin Luther King's Vision Change the World? . [Online]. Available at: https://studymoose.com/how-did-martin-luther-kings-vision-change-the-world-essay [Accessed: 30 Aug. 2024]

"How Did Martin Luther King's Vision Change the World?." StudyMoose, Sep 13, 2020. Accessed August 30, 2024. https://studymoose.com/how-did-martin-luther-kings-vision-change-the-world-essay

"How Did Martin Luther King's Vision Change the World?," StudyMoose , 13-Sep-2020. [Online]. Available: https://studymoose.com/how-did-martin-luther-kings-vision-change-the-world-essay. [Accessed: 30-Aug-2024]

StudyMoose. (2020). How Did Martin Luther King's Vision Change the World? . [Online]. Available at: https://studymoose.com/how-did-martin-luther-kings-vision-change-the-world-essay [Accessed: 30-Aug-2024]

- How Did Martin Luther King Changed The World Pages: 2 (500 words)

- Martin Luther King's Nobel Prize Acceptance Speech: A Vision for Equality Pages: 3 (608 words)

- Martin Luther King's Influence on Today's World Pages: 3 (850 words)

- Martin Luther King Jr Speech Compared to a Raisin in the Sun Pages: 2 (368 words)

- The Impact of Martin Luther King’s Philosophy of non-violence Pages: 5 (1340 words)

- Comparison of speeches by Barrack Obama and Martin Luther King Pages: 6 (1781 words)

- Research Paper: Malcolm X & Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Pages: 7 (1963 words)

- The Six Principles of Nonviolence by Martin Luther King, Jr. Pages: 8 (2305 words)

- The Message of Martin Luther King Jr. in His Letter From Birmingham Jail Pages: 7 (1867 words)

- Comparative Analysis: Martin Luther King and Winston Churchill's Rhetoric Pages: 5 (1245 words)

👋 Hi! I’m your smart assistant Amy!

Don’t know where to start? Type your requirements and I’ll connect you to an academic expert within 3 minutes.

- The Big Think Interview

- Your Brain on Money

- Explore the Library

- The Universe. A History.

- The Progress Issue

- A Brief History Of Quantum Mechanics

- 6 Flaws In Our Understanding Of The Universe

- Michio Kaku

- Neil deGrasse Tyson

- Michelle Thaller

- Steven Pinker

- Ray Kurzweil

- Cornel West

- Helen Fisher

- Smart Skills

- High Culture

- The Present

- Hard Science

- Special Issues

- Starts With A Bang

- Everyday Philosophy

- The Learning Curve

- The Long Game

- Perception Box

- Strange Maps

- Free Newsletters

- Memberships

5 ways Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. changed American history

It was 50 years ago on April 4th, 1968 that millions across the United States and the world were stunned to learn that Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. had been assassinated. Prior to that, for many people, the simple knowledge that Dr. King was out there somewhere working to make the world a better, fairer place had been a comfort, and his killing came as a gut-wrenching shock. People who followed the activist preacher more closely — and certainly King himself — were less surprised. In 1966, after all, a bomb had exploded on the porch of the King residence and death threats were a daily occurrence for his family; he was also surveilled with suspicion by the U.S. government. The night before he died, King spoke to a crowd in Memphis:

Well, I don’t know what will happen now; we’ve got some difficult days ahead. But it really doesn’t matter to with me now, because I’ve been to the mountaintop. And I don’t mind. Like anybody, I would like to live a long life — longevity has its place. But I’m not concerned about that now. I just want to do God’s will. And He’s allowed me to go up to the mountain. And I’ve looked over, and I’ve seen the Promised Land. I may not get there with you. But I want you to know tonight, that we, as a people, will get to the Promised Land. And so I’m happy tonight; I’m not worried about anything; I’m not fearing any man. Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord.

Dr. King’s signature insights

Some of King’s signature insights:

- Those in power can be expected to divide people against each other and use those divisions to provoke violence. However, strategic protest can neutralize those outcomes.

- Media, especially television, is a powerful platform that can be leveraged to reach the heart of the American public.

The tactics of power that King wanted to defeat

The nasty game of us vs. them.

The idea here is to pick a characteristic held by some people within the population and promote those people as somehow different and responsible for everyone else’s hardships. It may be skin color, it may be religion, but whoever the target is, the intention is to create a decoy enemy: they want our money, they want our possessions, they’re taking over, they’re denying us what’s rightfully ours.

It’s a devastatingly effective trick because it distracts from the true problem, presenting a make-believe zero-sum game where either you win or they do. In reality, however, what is being fought over is merely what remains after the powerful have satiated themselves.

The trick is especially insidious because people lower and lower in the power structure — having taken the bait — are more willingly join in. At that point, us vs. them rationalizes cruelty toward others as the freedom to protect one’s domain.

Us vs. them is not just an illusion for the masses — it serves equally well as a self-delusion for the powerful. Consider slaveholders who chose to view their slaves somehow different, somehow less , and unworthy of consideration or fair treatment.

Provocation of violence as an excuse for repression

When people do speak up, particularly as a group, the powerful have the option of silencing them using armed police, military personnel, and so on. However, to preserve the illusion that the problem is with the fictional them , authorities may deliberately provoke — or even invent — a violent act on the part of people raising their voice to justify the deployment of brutal force. It’s a trick that’s been employed when workers went on strike , and we still see it today when agitators, some of whom are planted by opponents of the cause being promoted, appear at gatherings and attempt to provoke violence.

Dr. King’s legacy

King’s struggle sadly continues in 2018. There have been steps both forward and back across the racial divide he sought for years to bridge. Late in life, King focused on the problem of economic inequality, which has gotten worse since his death.

We’re still easily divided against each other by fear, and inexcusable violence is excused by those in power on a regular basis. Still, there’s reason to hope: Progress eventually tends to move forward. Nonetheless, King’s lasting impact is indelible and multifaceted, his life a model of commitment and his strategy a continuing influence on those still struggling for positive change in America and throughout the world. Across the globe over a thousand streets have been renamed in tribute. Here are five examples of his lasting impact.

1. Dr. King was the first to master TV as a force for change

America watched the charismatic, captivating King as he spoke, marched and was attacked and arrested. Through him, the entire nation began, at last, to see just how false the us vs. them narrative really was. Racial discrimination was no longer something that only its victims had to reckon with, but a grave problem for the American soul. Designed to be viewed from the average Joe’s couch, King devised political spectacle that would inevitably attract TV coverage that just as inevitably changed the heart of a nation.

King’s gatherings provided a model that still works. Even in 2018, the sight of crowds gathering for an idea remains powerful in demonstrations such as 2017’s Women’s March and the March for Our Lives rallies this year in the wake of the Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School shooting.

2. America began to confront its post-slavery race problem

King would no doubt be the first to remind us that he traveled with many others on the road towards the end of legal segregation in the United States and the federal Civil Rights Act of 1964 and Voting Rights Act of 1964. Still, it would be difficult to overstate the magnitude of his personal oratory and influence, and the fundamental way that it changed America’s understanding of both its racial history and its current culture.

3. Showing America to itself

Most people know by now that there’s no such thing as race, biologically — it’s simply an arbitrary social construct . By so eloquently invoking our moral obligations to each other, King made it clear that we’re all in this together, and as a result, a gathering of his supporters was a tapestry of people in all shades, sizes, ages, and genders.

To watch a rally on TV such as in 1963’s March on Washington for Freedom and Jobs was to see a new, vital United States. Not the white one depicted on our other shows or in history books taught from in schools. It was the first good look Americans got at themselves.

4. The power of non-violence demonstrated

King advocated non-violence categorically and weathered his critics who said that violence was the only way to truly get oppressors’ attention.

Non-violence allowed King to keep attention focused on the issues at hand while allowing people of good conscience to participate (and feel safer doing so). On a more strategic level, though, he was well aware that non-violence may be returned with violence, resulting in TV coverage that would help the viewing public to sympathize with his cause and pierce any indifference to racial issues

5. Poverty is not just a problem of theirs. It’s everyone’s problem.

Towards the end of his life, King had refocused his efforts on the pernicious and devastating effects of poverty, regardless of its victims’ complexions. He saw inequality growing, and as a crucial danger to the entire nation. In 1968 when he died, 12.8% lived below the poverty line. The number in 2016 was 14%.

To listen to some, welfare in the U.S. today primarily benefits black Americans and immigrants. It’s not true : Poor whites receive the lion’s share of government money. Of the 70 million Medicare beneficiaries in 2016, 43% were white, 18% black, and 30% Hispanic. 36% of the 43 million food stamp recipients that year were white, 25.6% black, and 17.2% Hispanic (the remaining recipients are unknown).

Difficult days ahead

We are still far from King’s promised land. Yet no matter how heartbreaking the setbacks are, forward is the only direction we can go. Race is not even a consideration in contemporary music, TV, and films. We just need to keep calm — as King preached — and take care of each other as we travel forward together. In the long run, there’s simply no other sensible choice. We may yet arrive.

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- Games & Quizzes

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

Martin Luther King, Jr. summary

Learn about the life of martin luther king, jr., and his role in the civil rights movement in the united states.

Martin Luther King, Jr. , (born Jan. 15, 1929, Atlanta, Ga., U.S.—died April 4, 1968, Memphis, Tenn.), U.S. civil rights leader.

The son and grandson of Baptist preachers, King became an adherent of nonviolence while in college. Ordained a Baptist minister himself in 1954, he became pastor of a church in Montgomery, Ala.; the following year he received a doctorate from Boston University. He was selected to head the Montgomery Improvement Association, whose boycott efforts eventually ended the city’s policies of racial segregation on public transportation.

In 1957 King formed the Southern Christian Leadership Conference and began lecturing nationwide, urging active nonviolence to achieve civil rights for Black Americans. In 1960 he returned to Atlanta to become copastor with his father of Ebenezer Baptist Church. He was arrested and jailed for protesting segregation at a lunch counter; the case drew national attention, and presidential candidate John F. Kennedy interceded to obtain his release.

In 1963 King helped organize the March on Washington, an assembly of more than 200,000 people at which he made his famous “I Have a Dream” speech. The march influenced the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, and King was awarded the 1964 Nobel Prize for Peace.

In 1965 he was criticized from within the civil rights movement for yielding to state troopers at a march in Selma, Ala., and for failing in the effort to change Chicago’s housing segregation policies. Thereafter he broadened his advocacy, addressing the plight of the poor of all races and opposing the Vietnam War. In 1968 he went to Memphis, Tenn., to support a strike by sanitation workers; there on April 4, he was assassinated by James Earl Ray.

A U.S. national holiday is celebrated in King’s honour on the third Monday in January.

- This Day In History

- History Classics

- HISTORY Podcasts

HISTORY Vault

- Link HISTORY on facebook

- Link HISTORY on twitter

- Link HISTORY on youtube

- Link HISTORY on instagram

- Link HISTORY on tiktok

✯ ✯ ✯ Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. ✯ ✯ ✯ His Life and Legacy

Martin Luther King Jr. dedicated his life to the nonviolent struggle for civil rights in the United States. King's leadership played a pivotal role in ending entrenched segregation for African Americans and to the creation of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, considered a crowning achievement of the civil rights era. King was assassinated in 1968, but his words and legacy continue to resonate for all those seeking justice in the United States and around the world. As King said at the Washington National Cathedral on March 31, 1968, "Darkness cannot drive out darkness; only light can do that. Hate cannot drive out hate; only love can do that."

10 Things You May Not Know About Martin Luther King Jr.

An Intimate View of MLK Through the Lens of a Friend

The Fight for Martin Luther King Jr. Day

7 of Martin Luther King Jr.'s Most Notable Speeches

Martin Luther King Jr.

7 Things You May Not Know About MLK’s 'I Have a Dream' Speech

America in Mourning After MLK's Shocking Assassination: Photos

For Martin Luther King Jr., Nonviolent Protest Never Meant ‘Wait and See’

How an Assassination Attempt Affirmed MLK’s Faith in Nonviolence

Jesse Jackson on M.L.K.: One Bullet Couldn’t Kill the Movement

Martin Luther King Jr.’s Final Speech

MLK's Poor People's Campaign Demanded Economic Justice

Martin Luther King Jr.’s Famous Speech Almost Didn’t Have the Phrase 'I Have a Dream'

How Selma's 'Bloody Sunday' Became a Turning Point in the Civil Rights Movement

Playlist: Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

Watch the Black History collection on HISTORY Vault to look back on the history of African American achievements.

Get instant access to free updates.

Don’t Miss Out on HISTORY news, behind the scenes content, and more.

- Privacy Notice

- Terms of Use

Need help with the site?

Create a profile to add this show to your list.

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Critic’s Notebook

The Lasting Power of Dr. King’s Dream Speech

By Michiko Kakutani

- Aug. 27, 2013

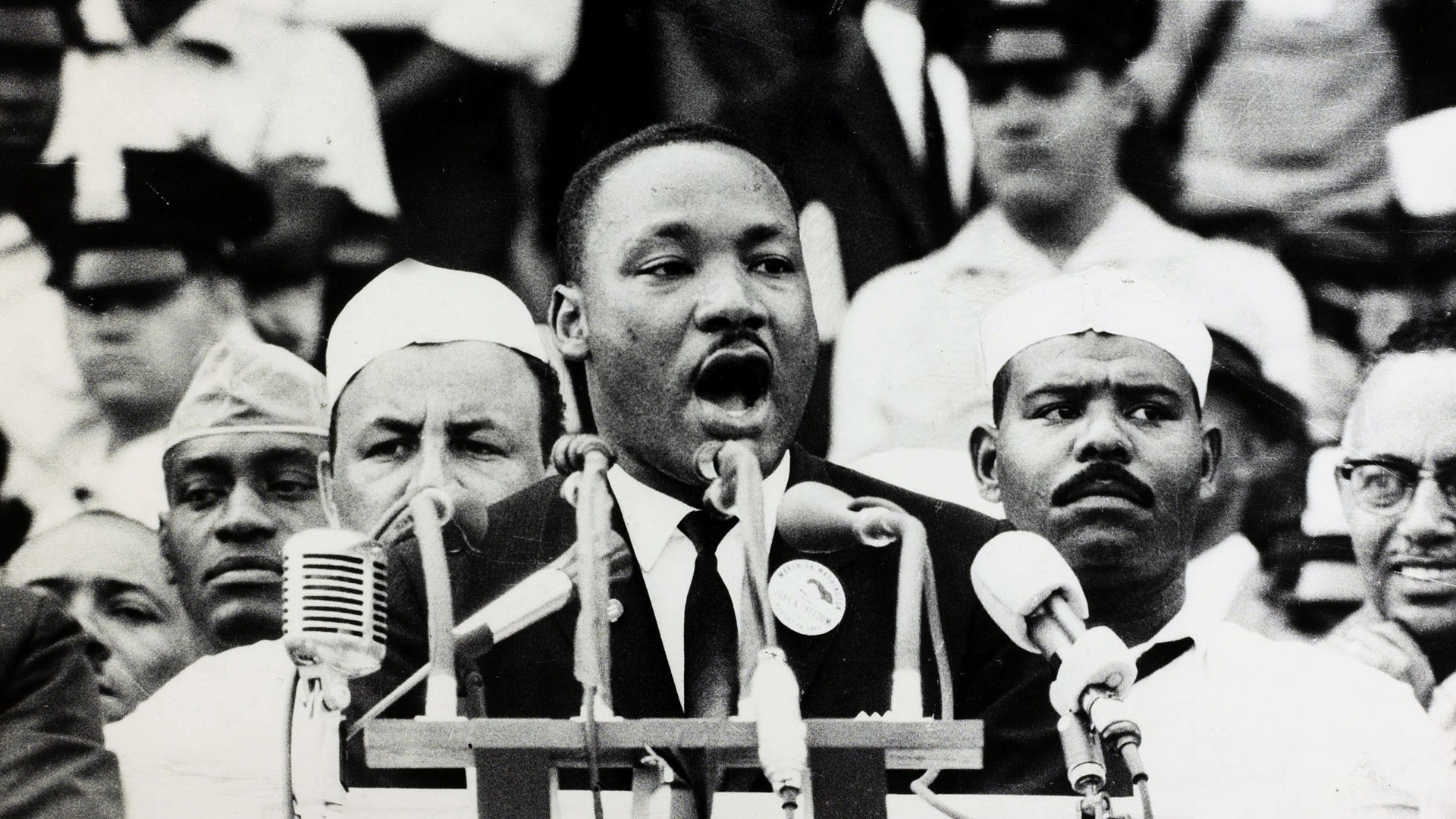

It was late in the day and hot, and after a long march and an afternoon of speeches about federal legislation, unemployment and racial and social justice, the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. finally stepped to the lectern, in front of the Lincoln Memorial, to address the crowd of 250,000 gathered on the National Mall.

He began slowly, with magisterial gravity, talking about what it was to be black in America in 1963 and the “shameful condition” of race relations a hundred years after the Emancipation Proclamation. Unlike many of the day’s previous speakers, he did not talk about particular bills before Congress or the marchers’ demands. Instead, he situated the civil rights movement within the broader landscape of history — time past, present and future — and within the timeless vistas of Scripture.

Dr. King was about halfway through his prepared speech when Mahalia Jackson — who earlier that day had delivered a stirring rendition of the spiritual “I Been ’Buked and I Been Scorned” — shouted out to him from the speakers’ stand: “Tell ’em about the ‘Dream,’ Martin, tell ’em about the ‘Dream’!” She was referring to a riff he had delivered on earlier occasions, and Dr. King pushed the text of his remarks to the side and began an extraordinary improvisation on the dream theme that would become one of the most recognizable refrains in the world.

With his improvised riff, Dr. King took a leap into history, jumping from prose to poetry, from the podium to the pulpit. His voice arced into an emotional crescendo as he turned from a sobering assessment of current social injustices to a radiant vision of hope — of what America could be. “I have a dream,” he declared, “my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character. I have a dream today!”

Many in the crowd that afternoon, 50 years ago on Wednesday, had taken buses and trains from around the country. Many wore hats and their Sunday best — “People then,” the civil rights leader John Lewis would recall, “when they went out for a protest, they dressed up” — and the Red Cross was passing out ice cubes to help alleviate the sweltering August heat. But if people were tired after a long day, they were absolutely electrified by Dr. King. There was reverent silence when he began speaking, and when he started to talk about his dream, they called out, “Amen,” and, “Preach, Dr. King, preach,” offering, in the words of his adviser Clarence B. Jones, “every version of the encouragements you would hear in a Baptist church multiplied by tens of thousands.”

You could feel “the passion of the people flowing up to him,” James Baldwin, a skeptic of that day’s March on Washington, later wrote, and in that moment, “it almost seemed that we stood on a height, and could see our inheritance; perhaps we could make the kingdom real.”

We are having trouble retrieving the article content.

Please enable JavaScript in your browser settings.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access. If you are in Reader mode please exit and log into your Times account, or subscribe for all of The Times.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access.

Already a subscriber? Log in .

Want all of The Times? Subscribe .

Nonviolence

As a theologian, Martin Luther King reflected often on his understanding of nonviolence. He described his own “pilgrimage to nonviolence” in his first book, Stride Toward Freedom , and in subsequent books and articles. “True pacifism,” or “nonviolent resistance,” King wrote, is “a courageous confrontation of evil by the power of love” (King, Stride , 80). Both “morally and practically” committed to nonviolence, King believed that “the Christian doctrine of love operating through the Gandhian method of nonviolence was one of the most potent weapons available to oppressed people in their struggle for freedom” (King, Stride , 79; Papers 5:422 ).

King was first introduced to the concept of nonviolence when he read Henry David Thoreau’s Essay on Civil Disobedience as a freshman at Morehouse College . Having grown up in Atlanta and witnessed segregation and racism every day, King was “fascinated by the idea of refusing to cooperate with an evil system” (King, Stride , 73).

In 1950, as a student at Crozer Theological Seminary , King heard a talk by Dr. Mordecai Johnson , president of Howard University. Dr. Johnson, who had recently traveled to India , spoke about the life and teachings of Mohandas K. Gandhi . Gandhi, King later wrote, was the first person to transform Christian love into a powerful force for social change. Gandhi’s stress on love and nonviolence gave King “the method for social reform that I had been seeking” (King, Stride , 79).

While intellectually committed to nonviolence, King did not experience the power of nonviolent direct action first-hand until the start of the Montgomery bus boycott in 1955. During the boycott, King personally enacted Gandhian principles. With guidance from black pacifist Bayard Rustin and Glenn Smiley of the Fellowship of Reconciliation , King eventually decided not to use armed bodyguards despite threats on his life, and reacted to violent experiences, such as the bombing of his home, with compassion. Through the practical experience of leading nonviolent protest, King came to understand how nonviolence could become a way of life, applicable to all situations. King called the principle of nonviolent resistance the “guiding light of our movement. Christ furnished the spirit and motivation while Gandhi furnished the method” ( Papers 5:423 ).

King’s notion of nonviolence had six key principles. First, one can resist evil without resorting to violence. Second, nonviolence seeks to win the “friendship and understanding” of the opponent, not to humiliate him (King, Stride , 84). Third, evil itself, not the people committing evil acts, should be opposed. Fourth, those committed to nonviolence must be willing to suffer without retaliation as suffering itself can be redemptive. Fifth, nonviolent resistance avoids “external physical violence” and “internal violence of spirit” as well: “The nonviolent resister not only refuses to shoot his opponent but he also refuses to hate him” (King, Stride , 85). The resister should be motivated by love in the sense of the Greek word agape , which means “understanding,” or “redeeming good will for all men” (King, Stride , 86). The sixth principle is that the nonviolent resister must have a “deep faith in the future,” stemming from the conviction that “The universe is on the side of justice” (King, Stride , 88).

During the years after the bus boycott, King grew increasingly committed to nonviolence. An India trip in 1959 helped him connect more intimately with Gandhi’s legacy. King began to advocate nonviolence not just in a national sphere, but internationally as well: “the potential destructiveness of modern weapons” convinced King that “the choice today is no longer between violence and nonviolence. It is either nonviolence or nonexistence” ( Papers 5:424 ).

After Black Power advocates such as Stokely Carmichael began to reject nonviolence, King lamented that some African Americans had lost hope, and reaffirmed his own commitment to nonviolence: “Occasionally in life one develops a conviction so precious and meaningful that he will stand on it till the end. This is what I have found in nonviolence” (King, Where , 63–64). He wrote in his 1967 book, Where Do We Go from Here: Chaos or Community? : “We maintained the hope while transforming the hate of traditional revolutions into positive nonviolent power. As long as the hope was fulfilled there was little questioning of nonviolence. But when the hopes were blasted, when people came to see that in spite of progress their conditions were still insufferable … despair began to set in” (King, Where , 45). Arguing that violent revolution was impractical in the context of a multiracial society, he concluded: “Darkness cannot drive out darkness: only light can do that. Hate cannot drive out hate: only love can do that. The beauty of nonviolence is that in its own way and in its own time it seeks to break the chain reaction of evil” (King, Where , 62–63).

King, “Pilgrimage to Nonviolence,” 13 April 1960, in Papers 5:419–425 .

King, Stride Toward Freedom , 1958.

King, Where Do We Go from Here , 1967.

Find anything you save across the site in your account

How Martin Luther Changed the World

Clang! Clang! Down the corridors of religious history we hear this sound: Martin Luther, an energetic thirty-three-year-old Augustinian friar, hammering his Ninety-five Theses to the doors of the Castle Church of Wittenberg, in Saxony, and thus, eventually, splitting the thousand-year-old Roman Catholic Church into two churches—one loyal to the Pope in Rome, the other protesting against the Pope’s rule and soon, in fact, calling itself Protestant. This month marks the five-hundredth anniversary of Luther’s famous action. Accordingly, a number of books have come out, reconsidering the man and his influence. They differ on many points, but something that most of them agree on is that the hammering episode, so satisfying symbolically—loud, metallic, violent—never occurred. Not only were there no eyewitnesses; Luther himself, ordinarily an enthusiastic self-dramatizer, was vague on what had happened. He remembered drawing up a list of ninety-five theses around the date in question, but, as for what he did with it, all he was sure of was that he sent it to the local archbishop. Furthermore, the theses were not, as is often imagined, a set of non-negotiable demands about how the Church should reform itself in accordance with Brother Martin’s standards. Rather, like all “theses” in those days, they were points to be thrashed out in public disputations, in the manner of the ecclesiastical scholars of the twelfth century or, for that matter, the debate clubs of tradition-minded universities in our own time.

If the Ninety-five Theses sprouted a myth, that is no surprise. Luther was one of those figures who touched off something much larger than himself; namely, the Reformation—the sundering of the Church and a fundamental revision of its theology. Once he had divided the Church, it could not be healed. His reforms survived to breed other reforms, many of which he disapproved of. His church splintered and splintered. To tote up the Protestant denominations discussed in Alec Ryrie’s new book, “ Protestants ” (Viking), is almost comical, there are so many of them. That means a lot of people, though. An eighth of the human race is now Protestant.

The Reformation, in turn, reshaped Europe. As German-speaking lands asserted their independence from Rome, other forces were unleashed. In the Knights’ Revolt of 1522, and the Peasants’ War, a couple of years later, minor gentry and impoverished agricultural workers saw Protestantism as a way of redressing social grievances. (More than eighty thousand poorly armed peasants were slaughtered when the latter rebellion failed.) Indeed, the horrific Thirty Years’ War, in which, basically, Europe’s Roman Catholics killed all the Protestants they could, and vice versa, can in some measure be laid at Luther’s door. Although it did not begin until decades after his death, it arose in part because he had created no institutional structure to replace the one he walked away from.

Almost as soon as Luther started the Reformation, alternative Reformations arose in other localities. From town to town, preachers told the citizenry what it should no longer put up with, whereupon they stood a good chance of being shoved aside—indeed, strung up—by other preachers. Religious houses began to close down. Luther led the movement mostly by his writings. Meanwhile, he did what he thought was his main job in life, teaching the Bible at the University of Wittenberg. The Reformation wasn’t led, exactly; it just spread, metastasized.

And that was because Europe was so ready for it. The relationship between the people and the rulers could hardly have been worse. Maximilian I, the Holy Roman Emperor, was dying—he brought his coffin with him wherever he travelled—but he was taking his time about it. The presumptive heir, King Charles I of Spain, was looked upon with grave suspicion. He already had Spain and the Netherlands. Why did he need the Holy Roman Empire as well? Furthermore, he was young—only seventeen when Luther wrote the Ninety-five Theses. The biggest trouble, though, was money. The Church had incurred enormous expenses. It was warring with the Turks at the walls of Vienna. It had also started an ambitious building campaign, including the reconstruction of St. Peter’s Basilica, in Rome. To pay for these ventures, it had borrowed huge sums from Europe’s banks, and to repay the banks it was strangling the people with taxes.

It has often been said that, fundamentally, Luther gave us “modernity.” Among the recent studies, Eric Metaxas’s “ Martin Luther: The Man Who Rediscovered God and Changed the World ” (Viking) makes this claim in grandiose terms. “The quintessentially modern idea of the individual was as unthinkable before Luther as is color in a world of black and white,” he writes. “And the more recent ideas of pluralism, religious liberty, self-government, and liberty all entered history through the door that Luther opened.” The other books are more reserved. As they point out, Luther wanted no part of pluralism—even for the time, he was vehemently anti-Semitic—and not much part of individualism. People were to believe and act as their churches dictated.

The fact that Luther’s protest, rather than others that preceded it, brought about the Reformation is probably due in large measure to his outsized personality. He was a charismatic man, and maniacally energetic. Above all, he was intransigent. To oppose was his joy. And though at times he showed that hankering for martyrdom that we detect, with distaste, in the stories of certain religious figures, it seems that, most of the time, he just got out of bed in the morning and got on with his work. Among other things, he translated the New Testament from Greek into German in eleven weeks.

Luther was born in 1483 and grew up in Mansfeld, a small mining town in Saxony. His father started out as a miner but soon rose to become a master smelter, a specialist in separating valuable metal (in this case, copper) from ore. The family was not poor. Archeologists have been at work in their basement. The Luthers ate suckling pig and owned drinking glasses. They had either seven or eight children, of whom five survived. The father wanted Martin, the eldest, to study law, in order to help him in his business, but Martin disliked law school and promptly had one of those experiences often undergone in the old days by young people who did not wish to take their parents’ career advice. Caught in a violent thunderstorm one day in 1505—he was twenty-one—he vowed to St. Anne, the mother of the Virgin Mary, that if he survived he would become a monk. He kept his promise, and was ordained two years later. In the heavily psychoanalytic nineteen-fifties, much was made of the idea that this flouting of his father’s wishes set the stage for his rebellion against the Holy Father in Rome. Such is the main point of Erik Erikson’s 1958 book, “ Young Man Luther ,” which became the basis of a famous play by John Osborne (filmed, in 1974, with Stacy Keach in the title role).

Today, psychoanalytic interpretations tend to be tittered at by Luther biographers. But the desire to find some great psychological source, or even a middle-sized one, for Luther’s great story is understandable, because, for many years, nothing much happened to him. This man who changed the world left his German-speaking lands only once in his life. (In 1510, he was part of a mission sent to Rome to heal a rent in the Augustinian order. It failed.) Most of his youth was spent in dirty little towns where men worked long hours each day and then, at night, went to the tavern and got into fights. He described his university town, Erfurt, as consisting of “a whorehouse and a beerhouse.” Wittenberg, where he lived for the remainder of his life, was bigger—with two thousand inhabitants when he settled there—but not much better. As Lyndal Roper, one of the best of the new biographers, writes, in “ Martin Luther: Renegade and Prophet ” (Random House), it was a mess of “muddy houses, unclean lanes.” At that time, however, the new ruler of Saxony, Frederick the Wise, was trying to make a real city of it. He built a castle and a church—the one on whose door the famous theses were supposedly nailed—and he hired an important artist, Lucas Cranach the Elder, as his court painter. Most important, he founded a university, and staffed it with able scholars, including Johann von Staupitz, the vicar-general of the Augustinian friars of the German-speaking territories. Staupitz had been Luther’s confessor at Erfurt, and when he found himself overworked at Wittenberg he summoned Luther, persuaded him to take a doctorate, and handed over many of his duties to him. Luther supervised everything from monasteries (eleven of them) to fish ponds, but most crucial was his succeeding Staupitz as the university’s professor of the Bible, a job that he took on at the age of twenty-eight and retained until his death. In this capacity, he lectured on Scripture, held disputations, and preached to the staff of the university.

He was apparently a galvanizing speaker, but during his first twelve years as a monk he published almost nothing. This was no doubt due in part to the responsibilities heaped on him at Wittenberg, but at this time, and for a long time, he also suffered what seems to have been a severe psychospiritual crisis. He called his problem his Anfechtungen —trials, tribulations—but this feels too slight a word to cover the afflictions he describes: cold sweats, nausea, constipation, crushing headaches, ringing in his ears, together with depression, anxiety, and a general feeling that, as he put it, the angel of Satan was beating him with his fists. Most painful, it seems, for this passionately religious young man was to discover his anger against God. Years later, commenting on his reading of Scripture as a young friar, Luther spoke of his rage at the description of God’s righteousness, and of his grief that, as he was certain, he would not be judged worthy: “I did not love, yes, I hated the righteous God who punishes sinners.”

There were good reasons for an intense young priest to feel disillusioned. One of the most bitterly resented abuses of the Church at that time was the so-called indulgences, a kind of late-medieval get-out-of-jail-free card used by the Church to make money. When a Christian purchased an indulgence from the Church, he obtained—for himself or whomever else he was trying to benefit—a reduction in the amount of time the person’s soul had to spend in Purgatory, atoning for his sins, before ascending to Heaven. You might pay to have a special Mass said for the sinner or, less expensively, you could buy candles or new altar cloths for the church. But, in the most common transaction, the purchaser simply paid an agreed-upon amount of money and, in return, was given a document saying that the beneficiary—the name was written in on a printed form—was forgiven x amount of time in Purgatory. The more time off, the more it cost, but the indulgence-sellers promised that whatever you paid for you got.

Actually, they could change their minds about that. In 1515, the Church cancelled the exculpatory powers of already purchased indulgences for the next eight years. If you wanted that period covered, you had to buy a new indulgence. Realizing that this was hard on people—essentially, they had wasted their money—the Church declared that purchasers of the new indulgences did not have to make confession or even exhibit contrition. They just had to hand over the money and the thing was done, because this new issue was especially powerful. Johann Tetzel, a Dominican friar locally famous for his zeal in selling indulgences, is said to have boasted that one of the new ones could obtain remission from sin even for someone who had raped the Virgin Mary. (In the 1974 movie “ Luther ,” Tetzel is played with a wonderful, bug-eyed wickedness by Hugh Griffith.) Even by the standards of the very corrupt sixteenth-century Church, this was shocking.

In Luther’s mind, the indulgence trade seems to have crystallized the spiritual crisis he was experiencing. It brought him up against the absurdity of bargaining with God, jockeying for his favor—indeed, paying for his favor. Why had God given his only begotten son? And why had the son died on the cross? Because that’s how much God loved the world. And that alone, Luther now reasoned, was sufficient for a person to be found “justified,” or worthy. From this thought, the Ninety-five Theses were born. Most of them were challenges to the sale of indulgences. And out of them came what would be the two guiding principles of Luther’s theology: sola fide and sola scriptura .

Sola fide means “by faith alone”—faith, as opposed to good works, as the basis for salvation. This was not a new idea. St. Augustine, the founder of Luther’s monastic order, laid it out in the fourth century. Furthermore, it is not an idea that fits well with what we know of Luther. Pure faith, contemplation, white light: surely these are the gifts of the Asian religions, or of medieval Christianity, of St. Francis with his birds. As for Luther, with his rages and sweats, does he seem a good candidate? Eventually, however, he discovered (with lapses) that he could be released from those torments by the simple act of accepting God’s love for him. Lest it be thought that this stern man then concluded that we could stop worrying about our behavior and do whatever we wanted, he said that works issue from faith. In his words, “We can no more separate works from faith than heat and light from fire.” But he did believe that the world was irretrievably full of sin, and that repairing that situation was not the point of our moral lives. “Be a sinner, and let your sins be strong, but let your trust in Christ be stronger,” he wrote to a friend.

The second great principle, sola scriptura , or “by scripture alone,” was the belief that only the Bible could tell us the truth. Like sola fide , this was a rejection of what, to Luther, were the lies of the Church—symbolized most of all by the indulgence market. Indulgences brought you an abbreviation of your stay in Purgatory, but what was Purgatory? No such thing is mentioned in the Bible. Some people think that Dante made it up; others say Gregory the Great. In any case, Luther decided that somebody made it up.

Guided by those convictions, and fired by his new certainty of God’s love for him, Luther became radicalized. He preached, he disputed. Above all, he wrote pamphlets. He denounced not only the indulgence trade but all the other ways in which the Church made money off Christians: the endless pilgrimages, the yearly Masses for the dead, the cults of the saints. He questioned the sacraments. His arguments made sense to many people, notably Frederick the Wise. Frederick was pained that Saxony was widely considered a backwater. He now saw how much attention Luther brought to his state, and how much respect accrued to the university that he (Frederick) had founded at Wittenberg. He vowed to protect this troublemaker.

Things came to a head in 1520. By then, Luther had taken to calling the Church a brothel, and Pope Leo X the Antichrist. Leo gave Luther sixty days to appear in Rome and answer charges of heresy. Luther let the sixty days elapse; the Pope excommunicated him; Luther responded by publicly burning the papal order in the pit where one of Wittenberg’s hospitals burned its used rags. Reformers had been executed for less, but Luther was by now a very popular man throughout Europe. The authorities knew they would have serious trouble if they killed him, and the Church gave him one more chance to recant, at the upcoming diet—or congregation of officers, sacred and secular—in the cathedral city of Worms in 1521. He went, and declared that he could not retract any of the charges he had made against the Church, because the Church could not show him, in Scripture, that any of them were false:

Since then your serene majesties and your lordships seek a simple answer, I will give it in this manner, plain and unvarnished: Unless I am convinced by the testimony of the scriptures or clear reason, for I do not trust in the Pope or in the councils alone, since it is well known that they often err and contradict themselves, I am bound to the Scriptures I have quoted and my conscience is captive to the Word of God. I cannot and will not retract anything.

Link copied

The Pope often errs! Luther will decide what God wants! By consulting Scripture! No wonder that an institution wedded to the idea of its leader’s infallibility was profoundly shaken by this declaration. Once the Diet of Worms came to an end, Luther headed for home, but he was “kidnapped” on the way, by a posse of knights sent by his protector, Frederick the Wise. The knights spirited him off to the Wartburg, a secluded castle in Eisenach, in order to give the authorities time to cool off. Luther was annoyed by the delay, but he didn’t waste time. That’s when he translated the New Testament.

During his lifetime, Luther became probably the biggest celebrity in the German-speaking lands. When he travelled, people flocked to the high road to see his cart go by. This was due not just to his personal qualities and the importance of his cause but to timing. Luther was born only a few decades after the invention of printing, and though it took him a while to start writing, it was hard to stop him once he got going. Among the quincentennial books is an entire volume on his relationship to print, “ Brand Luther ” (Penguin), by the British historian Andrew Pettegree. Luther’s collected writings come to a hundred and twenty volumes. In the first half of the sixteenth century, a third of all books published in German were written by him.

By producing them, he didn’t just create the Reformation; he also created his country’s vernacular, as Dante is said to have done with Italian. The majority of his writings were in Early New High German, a form of the language that was starting to gel in southern Germany at that time. Under his influence, it did gel.

The crucial text is his Bible: the New Testament, translated from the original Greek and published in 1523, followed by the Old Testament, in 1534, translated from the Hebrew. Had he not created Protestantism, this book would be the culminating achievement of Luther’s life. It was not the first German translation of the Bible—indeed, it had eighteen predecessors—but it was unquestionably the most beautiful, graced with the same combination of exaltation and simplicity, but more so, as the King James Bible. (William Tyndale, whose English version of the Bible, for which he was executed, was more or less the basis of the King James, knew and admired Luther’s translation.) Luther very consciously sought a fresh, vigorous idiom. For his Bible’s vocabulary, he said, “we must ask the mother in the home, the children on the street,” and, like other writers with such aims—William Blake, for example—he ended up with something songlike. He loved alliteration—“ Der Herr ist mein Hirte ” (“The Lord is my shepherd”); “ Dein Stecken und Stab ” (“thy rod and thy staff”)—and he loved repetition and forceful rhythms. This made his texts easy and pleasing to read aloud, at home, to the children. The books also featured a hundred and twenty-eight woodcut illustrations, all by one artist from the Cranach workshop, known to us only as Master MS. There they were, all those wondrous things—the Garden of Eden, Abraham and Isaac, Jacob wrestling with the angel—which modern people are used to seeing images of and which Luther’s contemporaries were not. There were marginal glosses, as well as short prefaces for each book, which would have been useful for the children of the household and probably also for the family member reading to them.

These virtues, plus the fact that the Bible was probably, in many cases, the only book in the house, meant that it was widely used as a primer. More people learned to read, and the more they knew how to read the more they wanted to own this book, or give it to others. The three-thousand-copy first edition of the New Testament, though it was not cheap (it cost about as much as a calf), sold out immediately. As many as half a million Luther Bibles seem to have been printed by the mid-sixteenth century. In his discussions of sola scriptura , Luther had declared that all believers were priests: laypeople had as much right as the clergy to determine what Scripture meant. With his Bible, he gave German speakers the means to do so.