- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Charles M. Blow

My Journey to Pride

By Charles M. Blow

Opinion Columnist

June is L.G.B.T.Q.+ Pride Month, a month in which people in the community affirm their identities, celebrate their culture, demonstrate their solidarity and assert their humanity. It presents a concentrated opportunity to be seen, in jubilation and triumph, to recognize the struggles, to commemorate the fallen and to honor the progress.

But I must say that I have had real struggles coming to embrace — and be embraced by — the institutional structures of the gay world.

(An editorial note: I use “gay” and, more often, “queer” as shorthand for the lettered grouping. As the Association for L.G.B.T.Q. Journalists has advised of the term “queer”: “Originally a pejorative term for gay, now reclaimed by some L.G.B.T.Q. people. Use with caution; still extremely offensive when used as an epithet and still offensive to many L.G.B.T.Q. people regardless of intent. Its use may require explanation.” I am in the reclamation camp.)

My coming out was unconventional and, to many, unacceptable. I came out late, in my 40s, after a heterosexual marriage. I came out as bisexual, which is viewed with suspicion and contempt by gay people as well as straight ones. And I apparently don’t have enough gay-obvious affectations for some people, although there are quite a few people in my high school who would beg to differ.

I was even asked recently in an interview why I wasn’t more gay, or something to that effect, because people who followed me would most likely not know that I was part of the queer community. I reminded my interviewer that I had written a best-selling book about my identity and that that book has been developed into an opera that will become the first opera by a Black composer to be staged at New York’s Metropolitan Opera in its history. What other queer man can make such a claim? How much more open can a person be?

But again, it was about affectation: I wasn’t projecting enough cultural cues. Being myself, naturally, comfortably, was somehow akin to concealment.

All of this has led to some rather biting pushback, some “How dare you speak for our community?” comments that took me by surprise. As far as I was able to discern, the resentment came from the fact that my decisions, designation and presentation meant that I had been able to avoid much of the struggle that other people couldn’t, that I arrived in the space after all the hard work had been done, after I was comfortable in my career, after I was liberated from much of what could have caused me pain and did cause others pain.

I had chosen an easy path. My suffering, such as it was, was insufficient.

Here it is important to say that this criticism almost never came from the Black gay community but from the white one. This critique may be divorced from race, but in my mind, a complete divorce is unachievable.

One of the most depressing realizations about queerness is that the racism in it is just as strong and stinging as the racism in the general population.

Indeed, it can be worse, as people who have been marginalized and mistreated become blind to the notion that they have their own biases. So I am quick to remind them: Yes, the hated can also hate. And for Black queer people, this means a double demerit.

It is far too easy for people to slip into racist tropes when discussing and considering queer Black men, to fetishize the fear of them, to project onto them a sort of brutish, animalistic, dangerous allure. But, of course, this is all rooted in racism, a fact that I can see clearly and one against which I constantly rage.

This is one reason I have been perfectly content with living outside the inner circles of gay power and thought, preferring rather to honor Blackness and Black gay people, to lift their stories and write about their struggles.

For the most part, you won’t find me on the gay magazine lists. I won’t be invited to the functions. I am not part of that version of Pride. And I am at peace with that.

My version is that I like to be with the forgotten and listen to the unheard. I like to talk with the older Black queer people, who impart incredible wisdom and give invaluable perspective about how our particular path in the queer space is distinct and our stories are our own.

I have found my own Pride in my own tribe, rooted in racial pride, rooted in a legacy of resilience, rooted in the power of truth and the power of community, my own community, and that community has embraced me, lifted me and loved me.

The Black community’s response to me may seem odd to those who exist outside it, but it was to me spiritually and culturally congruent. What I hear most is, we don’t care, do you, be careful, we love you, we are proud of you, we are praying for you.

I was on a journey to be whole, but it was the Black community, its embrace of my true self, my whole self, that finally made me whole.

You came out during a pandemic. What was that like?

During Pride Month, Opinion will be publishing various essays on the L.G.B.T.Q. community at this moment in history. We plan to publish a selection of your stories as part of that coverage.

The Times is committed to publishing a diversity of letters to the editor. We’d like to hear what you think about this or any of our articles. Here are some tips . And here’s our email: [email protected] .

Follow The New York Times Opinion section on Facebook and Twitter (@NYTopinion) , and Instagram .

Charles M. Blow joined The Times in 1994 and became an Opinion columnist in 2008. He is also a television commentator and writes often about politics, social justice and vulnerable communities. @ CharlesMBlow • Facebook

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Pride Month 2024

By: History.com Editors

Updated: May 21, 2024 | Original: May 8, 2023

Pride Month is an annual celebration of the many contributions made by the LGBTQ+ community to history, society and cultures worldwide. In most places, Pride is celebrated throughout the month of June each year in commemoration of its roots in the Stonewall Riots of June 1969. However, in some areas—especially in the Southern Hemisphere—pride events occur at other times of the year.

Origins of Pride Month

The roots of the gay rights movement go back to the early 1900s, when a handful of individuals in North America and Europe created gay and lesbian organizations such as the the Society for Human Rights, founded by Henry Gerber in Chicago in the 1920s.

Following World War II , a small number of groups like the Mattachine Society and the Daughters of Bilitis published gay- and lesbian-positive newsletters and grew more vocal in demanding recognition for, and protesting discrimination against, gays and lesbians. In 1966, for example, members of the Mattachine Society held a “sip-in” protest at Julius , a bar in New York City, where they demanded drinks after announcing that they were gay, in violation of local laws against serving alcohol to gays and lesbians.

Despite some progress in the postwar era, basic civil rights were largely denied to gay, lesbian, bisexual and transgender people—until one night in June, 1969, when the gay rights movement took a furious step forward with a series of violent riots in New York City.

Stonewall Riots

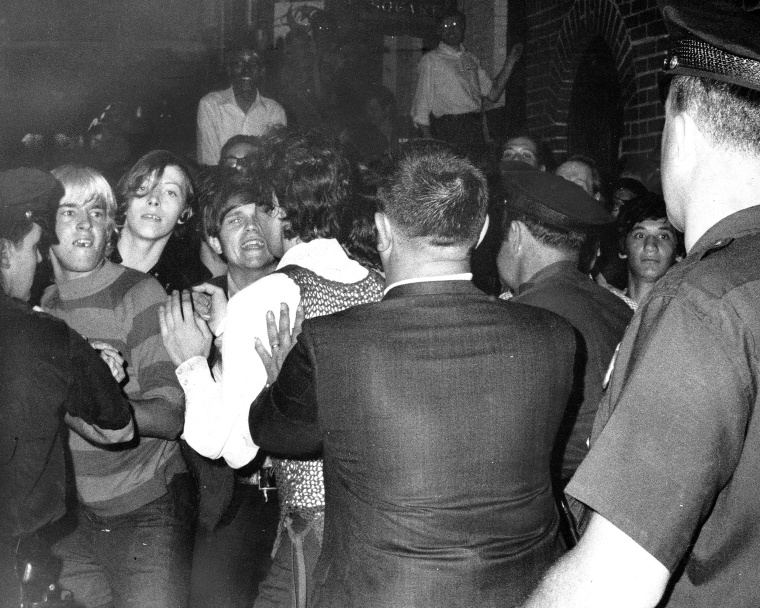

As was common practice in many cities, the New York Police Department would occasionally raid bars and restaurants where gays and lesbians were known to gather. This occurred on June 28, 1969, when the NYPD raided the Stonewall Inn , a bar in the Greenwich Village neighborhood of Manhattan.

When the police aggressively dragged patrons and employees out of the bar, several people fought back against the NYPD, and a growing crowd of angry locals gathered in the streets. The confrontations quickly escalated and sparked six days of protests and violent clashes with the NYPD outside the Stonewall Inn on Christopher Street and throughout the neighborhood.

By the time the Stonewall Riots ended on July 2, 1969, the gay rights movement went from being a fringe issue largely ignored by politicians and the media to front-page news worldwide.

First Gay Pride Parade

One year later, during the anniversary of the Stonewall Riots, activists in New York City marched through the streets of Manhattan in commemoration of the uprising. The march, organized by the Eastern Regional Conference of Homophile Organizations (ERCHO) and the Christopher Street Liberation Day Umbrella Committee, was named the Christopher Street Liberation Day March.

In time, that celebration came to be simply known as the Gay Pride Parade. According to activist Craig Schoonmaker, “I authored the word ‘pride’ for gay pride … [my] first thought was ‘Gay Power.’ I didn’t like that, so proposed gay pride. There’s very little chance for people in the world to have power. People did not have power then; even now, we only have some. But anyone can have pride in themselves, and that would make them happier as people, and produce the movement likely to produce change.”

The march, which took place on June 28, 1970, is now considered the country’s first gay pride parade . By all accounts, the New York City event was a stunning success, with an estimated 3,000 to 5,000 participants in the march, which stretched 51 blocks from Greenwich Village to Central Park. Marches and parades also took place that June in Chicago, Los Angeles and San Francisco.

7 LGBTQ Uprisings Before Stonewall

The 1969 Stonewall Riots marked a historic turning point for gay rights, but several smaller uprisings preceded Stonewall as LGBTQ communities pushed back against harassment and inequality.

The gay rights movement in the United States began in the 1920s and saw huge progress in the 2000s, with laws prohibiting homosexual activity struck down and a Supreme Court ruling legalizing same‑sex marriage.

The Gay ‘Sip‑In’ that Drew from the Civil Rights Movement to Fight Discrimination

In 1966, three men walked into a bar, stated they were gay and ordered drinks. When they were denied service, a movement began.

Gay Pride Month

Over the years, gay pride events have spread from large cities to smaller towns and villages worldwide—even in places where repression and violence against gays and lesbians are commonplace. The atmosphere at these events can range from raucous, carnivalesque celebrations to strident political protest to solemn memorials for those lost to AIDS or homophobic violence.

In June 2000, President Bill Clinton officially designated June as Gay and Lesbian Pride Month, in recognition of the Stonewall Riots and gay activism throughout the years. A more-inclusive name was chosen in 2009 by President Barack Obama : Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Pride Month.

The origins of Gay Pride Month were also honored by Obama when, in 2016, he created the Stonewall National Monument , a 7.7-acre around the Stonewall Inn where the modern gay rights movement began.

What Does LGBTQ+ Stand For?

According to the Human Rights Campaign , LGBTQ+ is an acronym that stands for "lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer (or "questioning"), with a "+" sign to recognize limitless sexual orientations and gender identities.

Pride Celebrations Around the World

Today, Gay Pride parades in many cities are enormous celebrations: The events in Sao Paulo, Sydney, New York City, Madrid, Taipei and Toronto routinely attract up to 5 million attendees.

The following U.S. Pride events are planned for 2024:

- Washington, D.C. - June 8 (Parade), June 9 (Festival). Theme: “ Totally Radical .”

- Los Angeles - June 8 (Festival) - June 9 (Parade). Theme: “ Power in Pride ”

- NYC Pride March - June 25. Theme: " Reflect. Empower. Unite. "

- Chicago - June 30 (Parade), June 22-23 (Pride Fest). Theme: “ Pride is Power ”

- San Francisco: June 29-30 (Parade). Theme: “ Beacon of Love .”

As Pride Month has grown in popularity across the globe, criticism of the events has grown, too. Some early organizers now decry the commercial influence and corporate nature of Pride parades—especially when those corporations make donations to politicians who vote against gay, lesbian and transgender rights.

Gay Pride events are nonetheless seen as vital protests against repression and isolation in places such as Serbia, Turkey and Russia, where Pride parades have been met with antigay violence. Even in the United States, a rise in bloodshed, killings and threats at Pride and other gay events and gatherings highlights the oppression the LGBTQ+ community still faces.

Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender and Queer Pride Month. Library of Congress . History of June’s recognition as LGBT Pride Month. Defense Logistics Agency . NYPD Commissioner Apologizes For 'Oppressive' 1969 Raid On Stonewall Inn. NPR . Allusionist 12: Pride. Craig Schoonmaker interview. 2015. The Allusionist . LGBTQ+ Pride Month. National Archives . The History of Pride: How Activists Fought to Create LGBTQ+ Pride. Library of Congress . Top 10 Pride Events Around the World. Flight Centre . What Is Pride Month and the History of Pride? them.us . A far-right plan to riot near an Idaho LGBTQ event heightens safety concerns at Pride. NPR . Pride events targeted in surge of anti-LGBTQ threats, violence. The Washington Post .

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

The Importance of Pride Month

Lgbtqi+ rights are human rights, but unfortunately, that still isn't status quo..

Posted June 10, 2021 | Reviewed by Chloe Williams

- The first recorded march for LGBTQI+ rights in the United States was in 1969 in New York City. Now, 150 cities host Pride events.

- In the U.S., LBTQI+ youth are almost five times more likely to have attempted suicide compared to heterosexual, cisgender youth.

- Pride Month and pride parades continue to be important for the solidarity, fight for human rights, and visibility of the LGBTQI+ community.

This month is LGBTQI+ Pride Month. In the US and other countries, many places display rainbow flags, companies have promotions, events, or products “in honor of LGBTQI+ Pride,” and there are cities around the world that have a parade sometime in the month of June.

That said, many people don’t know or understand why Pride Month exists and/or the purpose of the parade. Some react with fear and prejudice , some are puzzled as to why it’s necessary, while others think of it as just a big excuse to dress up and party.

But LGBTQI+ Pride Month actually has a very specific history and purpose. For many, if not most, in the LGBTQI+ community, it’s a deeply meaningful and moving day that has great significance.

Understanding the history of Pride

In order to understand Pride Month and why there are pride parades, it’s important to understand the history. The first recorded march for the rights of LGBTQI+ folks in the United States was in 1969 in New York City. The regular, systematic, and violent oppression of people in that community reached a boiling point, at a time when other social movements — the Civil Rights movement, Women’s Liberation movement, Disability Rights movement — were gaining momentum and fighting for oppressed groups to have a voice and demand for equal human treatment.

At that time, the police, and individuals felt it well within their rights to oppress and cause bodily harm to people within the LGBTQI+ community. The march was a response to that treatment — it was a demand that people within the community be treated with the basic rights, respect, and dignity afforded other human beings in the country.

Those first marchers were courageous. They risked their lives by exposing themselves to the public as part of the community and in doing so, they made the community visible and empowered. After this first march, it became an annual event. The next year there were also marches in Los Angeles and San Francisco. Today, there are 150 cities around the world that host Pride events during the summer.

So why are these events still happening?

Prejudice, oppression, violence, and death are still, unfortunately, common for people in the LBTQI+ community in the United States and across the globe. Many states in the US are continuing to pass legislation to deny the rights of people in this community. In the US, LBTQI+ youth are almost five times as likely to have attempted suicide compared to heterosexual, cis youth because of the continued deep prejudice, hatred, and lack of acceptance they perceive around them.

Around the world, there are laws specifically being passed to deny the rights of LBTQI+ people to live, love, work, receive medical care, go to the bathroom, exercise, and even simply exist. People in this community continue to be subjected to rejection, prejudice, violence, and death.

For this reason, Pride Month — and the pride parades — continue to be deeply important in the continued solidarity, fight for human rights, and visibility of the LGBTQI+ community. Additionally, and equally important, is the label “pride.” For a group of people who are told continuously — through laws, religions, media, bullying , and directly — that LBTQI+ people are less-than or should not exist, it is deeply psychologically important that there be counter-messaging. Shame is debilitating and can lead to mental illness, addiction , isolation, and death .

It is deeply important that there be a visible, supported, and joyous event telling people of the LBTQI+ community that it is a beautiful, diverse, supported, and welcome community, and one to be proud to be a member of, and one that deserves the rights and dignities of every human.

Samantha Stein , Psy.D., is a psychologist in private practice in San Francisco. She works with couples and individuals, specializing in intimacy, sexuality, and self-realization.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Self Tests NEW

- Therapy Center

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

It’s increasingly common for someone to be diagnosed with a condition such as ADHD or autism as an adult. A diagnosis often brings relief, but it can also come with as many questions as answers.

- Emotional Intelligence

- Gaslighting

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

This Pride, Embody the True Spirit of Queer Liberation

:upscale()/2024/06/05/762/n/49351773/tmp_QHs2ew_e14a5e16aef618e7_Main_PS24_05_Identity_PrideProtests_1456x970.jpg)

As we enter another Pride Month overrun with corporate rainbows and empty overtures, it's important to remember that Pride started as a protest — a riot, to be more specific. On a hot June day in 1969 when the New York Police Department raided the popular Stonewall Inn, Queer folks fought back, sparking a days-long riotous rebellion against police repression, youth homelessness, discrimination, and more. This moment of resistance sparked what would become a global movement against repression, oppression, marginalization, and violence.

Since long before the Stonewall Rebellion into the present, the spirit of Queer Pride has been about full liberation for all the weirdos, the deviants, and all those living on the margins of society. The entrance of the capital Q "Queer" into the social-political lexicon encapsulates this perfectly: it came from young gay and lesbian activists in the 1990s who sought to embody a politics of disruption in line with the way their gender and sexuality were inherently disruptive. In the seminal text "Punks, Bulldaggers, and Welfare Queens: The Radical Potential of Queer Politics?," Cathy Cohen describes Queer as "an acknowledgment that through our existence and everyday survival we embody sustained and multi-sited resistance to systems." To be Queer is to disrupt social norms, so it also contains infinite potential for radical disruption in the normalization of power indifference everywhere.

"This June, it's important to reflect on the responsibility of embodying Queer politics in your daily life."

This June, it's important to reflect on the responsibility of embodying Queer politics in your daily life. For me, organizing in and around the South has brought me closer to Queer community than I've ever felt before. We organize not just against big systems, but to actually take care of each other in the present. Whether it's fundraising to cover each other's rent , dropping off meals and medicine, checking in during the highs and the lows, or sharing the load of child bearing, my most loving and liberated relationships are those where we work to survive the world together. We study together, we cover each other for prayer, we actively build space in the world to hold all of us. The choice to leave apathy behind and instead engage in the fight for our lives is no small one, but I've learned the most about myself, my values, and the true meaning of liberation by being in loving, principled community.

Despite companies engaging in dubious rainbow marketing every year, safety continues to be precarious for Queer folks and especially Queer youth. According to The Trevor Project , "28% of LGBTQ youth reported experiencing homelessness or housing instability at some point in their lives — and those who did had two to four times the odds of reporting depression, anxiety, self-harm, considering suicide, and attempting suicide compared to those with stable housing."

Queer youth are under attack from all sides, as trans healthcare bans and curriculum bans continue to sweep the nation. Now more than ever, young Queer folks need their community's support. The need for disruption is palpable and urgent.

Building a world that is truly safe for all requires us to contribute to community building across identities. Anyone can start a neighborhood food distribution or mutual aid project , volunteer with a local youth project or start their own. Connect with abolitionist projects pushing back against the criminalization of Queer and trans survivors. Organize to provide stable housing, mental health services, and loving community to young Queer kids. Our Queer ancestors fought for us to retain our position in our communities as culture bearers, healers, artists and more. Community is built, not given — everyone holds a role in the web of world-building.

For those particularly frustrated with the treatment of Queer students in schools, consider joining your local school board. Queer students are harmed most when depictions of Queer sexuality are omitted from school libraries and curriculum and when teachers face threats of termination if they don't out students to their parents. Right-wing, homophobic organizations have packed school boards to promote the regressive changes they want to see. We can organize and fight for all young people to have access to quality sex education , Queer history, and Queer-affirming educational spaces, and joining your local school board is a direct way to do so. Talk to your teacher friends, too — despite threats to their careers, Queer and allied teachers have been fighting mercilessly to protect our young people in and out of the classroom. Schools are also often in need of volunteer reading partners, coaches, mentors, and more. Intergenerational community building is vital to the spirit of Pride. There are ways for everyone to plug in with local Queer youth and have a positive impact on their lives.

And as Israel continues its invasion of Rafah despite the ICJ issuing arrest warrants to halt the violence, it's important to recognize how the Zionist regime is pinkwashing their colonial project . Queer Palestinians have fought for years to push back against the narrative that Palestine is unsafe for Queer folks. As we continue to build a global movement in solidarity with Palestine and all people suffering under violent regimes, fight this narrative at home, at work, with your friends, and anywhere where Queer folks are propped up to elide other violence.

"I'm holding my community a little closer this month for all those we've lost and all the work it takes to survive in a world bent on squashing us."

The daily work of Queer liberation looks like care, resistance, and a commitment to liberation for all. Care can look like battling our own internalized homophobia and transphobia to create safer communities for all Queer folks. Resistance can look like rejecting corporate attempts to take over Pride, and encouraging your friends to take on a mutual aid or youth mentorship project that truly embodies the spirit of Pride. More than a party or protest, Pride is an invitation to be our fullest selves and fight for a world where everyone is free to do the same. A commitment to liberation for all means continuing to fight for everyone to live free of violence and injustice.

This June, honor Pride by picking up the torch of Queer activism in your workplace, school, or community. Every day is a chance to inch toward completing the project of Queer liberation, together. I'm holding my community a little closer this month for all those we've lost and all the work it takes to survive in a world bent on squashing us. Later this month, I'll have my closest homies over for a dinner party where we'll celebrate each other, mourn our martyrs, and plant seeds for the future.

Jasmine Butler is a Black, queer, Southern writer, cultural worker, and afrofuturist abolitionist, among other things. Their nonfiction has been featured in HoodCommunist, TransLash, and multiple nonprofit blogs. Their fiction has appeared on Inherited Podcast, Ebony Tomatoes Collective, and Torch Literary Arts. Jasmine is also an Outreach Editor at Apogee Journal where they publish incarcerated writers.

- Personal Essay

- Pride Month

- US Politics

Shop TODAY’s Hot List: Get gifting inspo with these expert-loved ideas

- Share this —

- Watch Full Episodes

- Read With Jenna

- Inspirational

- Relationships

- TODAY Table

- Newsletters

- Start TODAY

- Shop TODAY Awards

- Citi Concert Series

- Listen All Day

Follow today

More Brands

- On The Show

- TODAY Plaza

What is Pride Month? What to know about the annual observance

Pride Month is official here, bringing events, marches, parades, festivities and remembrances dedicated to the LGBTQ community to U.S. cities and countries throughout the world.

The annual commemoration recognizes those who identify as LGBTQ community members, as well as their supporters and allies.

Pride Month events typically culminate on June 28, the anniversary of the 1969 Stonewall Uprising in New York City.

Though celebrations often mark the occasion, Pride is also a call for greater unity , visibility and equality for the LGBTQ community , as well as being a time to reflect on the history and milestones of the past 50 years.

What is the meaning of Pride Month? According to GLAAD , the annual recognition provides “an opportunity for the community to come together, take stock and recognize the advances and setbacks made in the past year. It is also a chance for the community to come together and celebrate in a festive, affirming atmosphere.”

To learn more about the month-long recognition, see below for facts on the meaning of Pride Month , the history behind why it's celebrated, the meaning of the rainbow flag, a list of notable 2024 events, as well as important resources and other helpful information.

Here's what you need to know.

What is Pride Month?

From June 1 to June 30, Pride Month spotlights LGBTQ voices and celebrates LGBTQ culture, achievements and activism through a series of organized activities, including film festivals , art exhibits, marches, concerts and other programs throughout the month.

Through these efforts, the LGBTQ community and its allies aim to spotlight LGBTQ voices , increase awareness and knowledge on issues of inequality, as well as commemorate the lives lost to violence and the AIDS crisis.

Why is Pride Month in June?

Pride Month is observed in June to honor the anniversary of the Stonewall Uprising, a touchstone event in LGBTQ history.

In the late 1960s, being openly gay was largely prohibited in most places. New York, in particular, had a rule that the simple presence of someone gay or genderqueer counted as disorderly conduct, effectively outlawing gay bars.

On June 28, 1969, patrons of the Stonewall Inn, a popular bar with a diverse LGBTQ clientele, stood their ground after police raided the establishment. The resulting clash led to days of riots and protests, known as the Stonewall Uprising.

One year later, on the anniversary of the Stonewall Uprising, thousands of people flooded the streets of Manhattan in the Christopher Street Gay Liberation Day March, regarded as the first gay pride event ever.

How did Pride Month begin?

Before Pride became a month-long commemoration, it was initially recognized as Gay Pride Day, observed annually on the last Sunday in June.

However, as awareness increased, more activities and events were planned spanning the entire month and, eventually, Gay Pride Day evolved into the month-long recognition we now observe as Pride Month.

The designation became official in 1999 when President Bill Clinton officially declared June as Gay and Lesbian Pride Month, setting aside the month as a time to recognize the LGBTQ community’s achievements and support the community.

What is the symbol of Pride?

The rainbow flag is universally recognized as the symbol for LGBTQ pride. It was created by renowned San Francisco activist Gilbert Baker.

According to Baker, “the rainbow of humanity" is intended to symbolize all genders and races.

Each of the six colors of the rainbow flag represent a different aspect of the LGBTQ movement: life, healing, sunlight, nature, serenity and spirit.

In 2017, Philadelphia added a black and brown stripe to their flag to symbolically represent LGBTQ people of color who have often felt marginalized from their own community.

Today, many organizations have adopted the flag, with some adding the colors of the transgender pride flag, which are baby blue and light pink.

You'll find a full list of LGBTQ flags along with their meanings right here .

How can I participate in Pride Month 2024?

Along with reading LGBTQ-inspired books or posting a meaningful Pride Month quote on Instagram, you can join in any of the nationwide celebrations held throughout the month of June.

One of the largest Pride marches occurs in New York City, the birthplace of modern gay rights movement. The NYC Pride parade will take place on Sunday, June 30, this year.

The annual event is one of the country's biggest Pride events, drawing nearly 2 million attendees.

Here’s a list of some U.S. cities hosting Pride Month events this year:

- Baltimore : June 10 — 16, 2024

- Chicago : Pride Fest, June 22 — 23, 2024; Pride Parade, June 22

- Denver : June 22 — 23, 2024

- Detroit : June 8 — 9, 2024

- Key West : June 5 — 9, 2024

- Los Angeles : June 8 -9, 2024

- Nashville : June 22 — 23, 2024

- New Orleans : June 7 — 9, 2024

- New York: June 30, 2024

- Philadelphia : June 2, 2024

- Portland : June 20 — 21, 2024

- Provincetown, RI : May 31 — June 2, 2024

- San Francisco : June 29 — 30, 2024

- Seattle : June 30, 2024

Other important dates during Pride Month

- June 5 : HIV Long-Term Survivors Day , honors and increases visibility around HIV survivor issues and needs

- June 12 : Pulse Remembrance Day , a remembrance of the 2016 Pulse nightclub shooting victims

- June 19 : Juneteenth , a commemoration of African American culture and the emancipation of African American slaves

- June 27 : National HIV Testing Day , encourages individuals to be tested for HIV

- June 28 : Stonewall Riots Anniversary , commemorates the 1969 Stonewall Uprising

- June 30 : Queer Youth of Faith Day , to celebrate and empower LGBTQ youth of different faiths

LGBTQ Pride Month resources

To learn more about Pride Month or find additional ways to get involved, check out the following resources:

- GLAAD , a non-government agency founded to promote LGBTQ acceptance along with identifying and preventing discrimination against lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer individuals.

- GLSEN , a network of students, families and education advocates working to facilitate LGBTQ safety and support in schools.

- The Equality Federation is a LGBTQ advocacy group working to help advance the rights of LGBTQ people.

- The National LGBTQ Task Force , an advocacy group dedicated to advancing freedom, justice and equality for LGBTQ people.

- The Library of Congress , for history on lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer Pride Month.

- The Anti-Defamation League , an anti-hate organization dedicated to fighting bias, extremism, discrimination or hate.

- The American Civil Liberties Union , works to preserve and defend the rights and liberties of U.S. citizens.

Celebrate Pride today and everyday

- Inspirational Pride Month quotes from luminaries

- A timeline of Pride: 50 defining LGBTQ milestones that shaped history

Sarah Lemire is a lifestyle and entertainment reporter for TODAY based in New York City. She covers holidays, celebrities and everything in between.

Here’s the full list of holidays and observances in November 2024

See Heidi Klum’s elaborate Halloween costumes over the years

60 no-carve pumpkin decorating ideas that are better than the real deal

10 haunted houses to visit during spooky season

How to watch 'It's the Great Pumpkin, Charlie Brown' this Halloween

The very best TODAY Halloween costumes through the years

TODAY Halloween extravaganza 2024: Live updates and costume reveals from the plaza

10 best movies to watch this Halloween

See Hoda Kotb’s Halloween costumes on TODAY through the years

95 spooky Halloween trivia questions and answers

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

Reflections On What Makes This Pride Month So Significant

NPR's Michel Martin reflects on the uniqueness of this Pride month with journalist Eric Marcus, attorney Christy Mallory and activist J. Clapp.

Copyright © 2020 NPR. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use and permissions pages at www.npr.org for further information.

NPR transcripts are created on a rush deadline by an NPR contractor. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of NPR’s programming is the audio record.

clock This article was published more than 2 years ago

The unbridled joy of queer bars

As a lesbian, i feel protected there from the outside world — no matter how much it tries to disrupt us.

Each week in June, we are publishing an essay by an LGBTQ writer that answers this question: Where do you find pride, joy and/or comfort in your own life, particularly amid a rise in anti-LGBTQ legislation? Check back here each Monday this month to read a new installment of the series.

A lot of LGBTQ people will be able to tell you about their first trip inside a gay bar. Mine? I was 17, and was snuck into a club called Outrageous, in Carlisle, northern England, by the lesbians on my football team.

The interior was as its name suggested. The window frames were a garish pink; they played Rihanna’s “S&M” every time I went; and off to one side, there was a model horse — taken from an old-fashioned carousel — that people would sit on and take photos of themselves. The club nicknamed the horse “Randy.”

As a young lesbian in the early 2010s, that place was like a royal palace to me. I’d seen some of the lesbian couples from football kissing before, but, in public, there was often an underlying trepidation to their affection: like someone could shout at them at any moment. (And, sometimes, someone did.)

But their anxiety dissipated inside Outrageous. Suddenly, they relaxed: Here were women kissing women and men holding men, with, well, gay abandon.

It’s been just over 10 years since then, and I now live in London, but LGBTQ clubs and venues remain among the places where I find the most joy. When I was a kid, I used to shake snow globes, then watch the snow settle, and see how those idyllic microcosms were undisturbed despite my efforts. That’s kind of how I feel inside queer spaces: protected from the outside world, no matter how much it tries to disrupt us.

I can only speak from personal experience — this won’t be the same as every other LGBTQ person — but, in every relationship of mine, I’ve been discriminated against. To be more specific: In every single one, I’ve been shouted at for holding hands in public. That includes multiple times in the past year in London; one time, we were followed by teenage boys on their bikes.

The number of gay bars has dwindled. A new generation plans to bring them back.

If you are straight, try to imagine that: what it would feel like to know that, at some point — not if, but when — you’ll get heckled for simply holding your partner’s hand. It might not bother you the first time, maybe not even in the second or third instance. But consider how 10 years of it, the length of time that I’ve been “out,” might grind you down. That’s the thing with discrimination: It’s exhausting. There is an attrition to it. I am tired of being shouted at.

What I’m trying to say is this: LGBTQ clubs are like sanctuaries to me; pink-lit paradises, where I can forget about all of that while flailing around to Robyn and Muna. They are among the few places where I can kiss whom I want, knowing I won’t get harassed.

In the past couple of months, the first time since before the pandemic, I’ve started going back to a club night called Butch, Please! Held in south London’s Royal Vauxhall Tavern — where Freddie Mercury is rumored to have once smuggled Princess Diana inside — the night is specifically for queer women, trans and nonbinary people, who are often sidelined on the gay nightlife scene in London.

I’d forgotten how important Butch, Please! is to me, as a butch lesbian; what it feels like to wade into a crowded floor and see who I am reflected in the people around me. In recent years, our various LGBTQ identities have been pitted against each other. But what I see during those events is a determined unity: a sweaty community of lesbians, queer women, transgender and nonbinary people dancing together to Olivia Rodrigo. There is a solidarity between those bodies pressed together, our identities in harmony — a sea of low-fade haircuts, piercings, tattoos — when it feels like the world is trying to rip us apart.

In the capital, some of my other favorites are Gal Pals — a night for queer women, nonbinary and trans people — alongside queer venues the Glory , a drag hot spot, and Dalston Superstore . Inside each of them, it’s the same feeling: I get this sheer thrill, an unrivaled liberation, that comes from not being in the minority, just for one night. There is something very beautiful in watching people come alive in a way we’d never do in the outside world.

Statistically, in recent years, LGBTQ people here have been less safe than ever. In England and Wales, anti-LGBTQ hate crimes rose every year in the five financial years up to 2021, according to official government statistics. Earlier this year , three people were convicted in the homophobic murder of Gary Jenkins, a bisexual man, in Cardiff, Wales. LGBTQ spaces have also been targeted. A few years ago in Cumbria, a white supremacist was jailed for his plot to carry out a “slaughter” at a gay pride night. In 2016, 49 people were killed in Orlando at the LGBTQ nightclub Pulse — exactly where they were supposed to be safe.

As a lesbian, I’m often subjected to a specific kind of homophobia: one laced with misogyny and the fetishization of my relationships. It is nearly always by men. In 2018 , 2019 and 2021 (2020 was missed out), “lesbian” was the most searched for term by U.K.-based users on Pornhub, according to its own data.

GOP lawmakers push historic wave of bills targeting rights of LGBTQ teens, children and their families

In the past couple of years, I have been asked for threesomes, had “lesbian” shouted at me in the street, and had kisses aggressively blown at me — all by men. In 2019 , two women were beaten up by a group of boys on a bus in London after they refused those boys’ demands for them to kiss. Globally, my sexuality continues to be persecuted (homosexuality is still criminalized in about 70 countries).

Going by the hate crime statistics, there is a greater need than ever for LGBTQ-specific spaces, including ones not centered around alcohol. ( Research has shown that LGBTQ people are disproportionately affected by substance abuse.) But the climate for LGBTQ venues in the United Kingdom — like in the United States, which has contended with a dwindling number of lesbian bars for years — is harsh. Between 2006 and 2017, more than 50 percent of London’s lesbian bars closed, according to one study . There is just one lesbian bar in London, She Soho. Outrageous closed in 2019.

I don’t know where I would be without LGBTQ spaces. As a closeted teenager, Outrageous made me feel less alone: I used to stand on the edge of the dance floor in my plaid shirt — my way of saying I was gay without actually saying it — avoiding eye contact and nervously smiling at the floor. That place, my royal palace, showed me that I’d be all right, eventually. (And I was.)

There is unbridled joy to be found inside those queer havens. Underneath those disco balls, there is so much freedom.

Ella Braidwood is a journalist and editor based in London.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

This student essay captures a gay student’s experience navigating the challenges inherent in being visible as a gay person, as well as the responsibility to honor the sacrifices of movement leaders past by being visible today.

June is L.G.B.T.Q.+ Pride Month, a month in which people in the community affirm their identities, celebrate their culture, demonstrate their solidarity and assert their humanity.

Pride Month is an annual celebration of the many contributions made by the LGBTQ+ community to history, society and cultures worldwide. In most places, Pride is celebrated throughout the month...

Pride Month and pride parades continue to be important for the solidarity, fight for human rights, and visibility of the LGBTQI+ community.

Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender and Queer (LGBTQ) Pride Month is currently celebrated each year in the month of June to honor the 1969 Stonewall Uprising in Manhattan.

In this personal essay, Jasmine Butler writes about the true spirit of Queer Pride and how we can all fight for liberation in 2024.

What is Pride Month exactly? Find out its history, why the rainbow flag became a Pride symbol and how you can celebrate this year.

NPR's Michel Martin reflects on the uniqueness of this Pride month with journalist Eric Marcus, attorney Christy Mallory and activist J. Clapp.

Each week in June, we are publishing an essay by an LGBTQ writer that answers this question: Where do you find pride, joy and/or comfort in your own life, particularly amid a rise in anti-LGBTQ...

In New York City, the Christopher Street Liberation Day March is considered the city’s first Pride parade. Today, June is celebrated as LGBTQ+ Pride Month in commemoration of the event. Photographic slide of Marsha P. Johnson at a New York Pride march in the 1980s.