- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

George Washington

By: History.com Editors

Updated: June 25, 2024 | Original: October 29, 2009

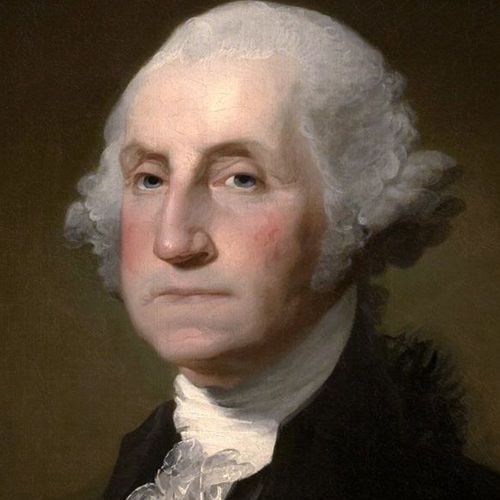

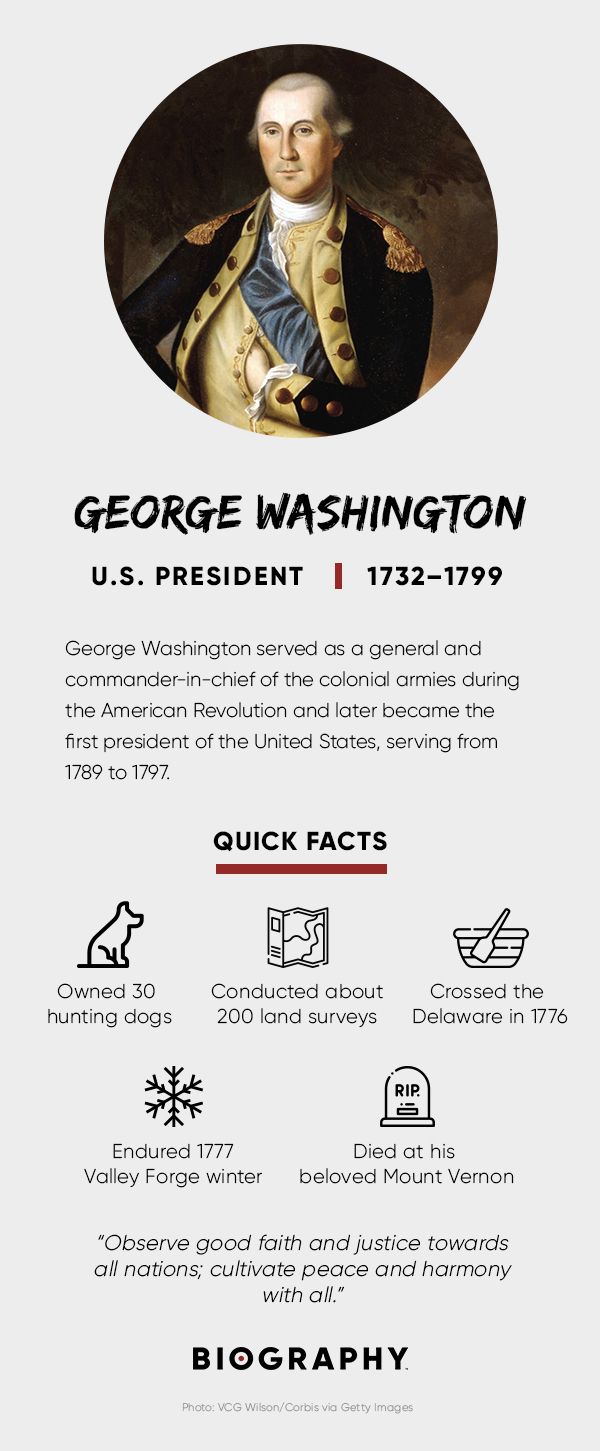

George Washington (1732-99) was commander in chief of the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War (1775-83) and served two terms as the first U.S. president, from 1789 to 1797. The son of a prosperous planter, Washington was raised in colonial Virginia. As a young man, he worked as a surveyor then fought in the French and Indian War (1754-63).

During the American Revolution, he led the colonial forces to victory over the British and became a national hero. In 1787, he was elected president of the convention that wrote the U.S. Constitution. Two years later, Washington became America’s first president. Realizing that the way he handled the job would impact how future presidents approached the position, he handed down a legacy of strength, integrity and national purpose. Less than three years after leaving office, he died at his Virginia plantation, Mount Vernon, at age 67.

George Washington's Early Years

George Washington was born on February 22, 1732 , at his family’s plantation on Pope’s Creek in Westmoreland County, in the British colony of Virginia , to Augustine Washington (1694-1743) and his second wife, Mary Ball Washington (1708-89). George, the eldest of Augustine and Mary Washington’s six children, spent much of his childhood at Ferry Farm, a plantation near Fredericksburg, Virginia. After Washington’s father died when he was 11, it’s likely he helped his mother manage the plantation.

Did you know? At the time of his death in 1799, George Washington owned some 300 enslaved people. However, before his passing, he had become opposed to slavery, and in his will, he ordered that his enslaved workers be freed after his wife's death.

Few details about Washington’s early education are known, although children of prosperous families like his typically were taught at home by private tutors or attended private schools. It’s believed he finished his formal schooling at around age 15.

As a teenager, Washington, who had shown an aptitude for mathematics, became a successful surveyor. His surveying expeditions into the Virginia wilderness earned him enough money to begin acquiring land of his own.

In 1751, Washington made his only trip outside of America, when he traveled to Barbados with his older half-brother Lawrence Washington (1718-52), who was suffering from tuberculosis and hoped the warm climate would help him recuperate. Shortly after their arrival, George contracted smallpox. He survived, although the illness left him with permanent facial scars. In 1752, Lawrence, who had been educated in England and served as Washington’s mentor, died. Washington eventually inherited Lawrence’s estate, Mount Vernon , on the Potomac River near Alexandria, Virginia.

An Officer and Gentleman Farmer

In December 1752, Washington, who had no previous military experience, was made a commander of the Virginia militia. He saw action in the French and Indian War and was eventually put in charge of all of Virginia’s militia forces. By 1759, Washington had resigned his commission, returned to Mount Vernon and was elected to the Virginia House of Burgesses, where he served until 1774. In January 1759, he married Martha Dandridge Custis (1731-1802), a wealthy widow with two children. Washington became a devoted stepfather to her children; he and Martha Washington never had any offspring of their own.

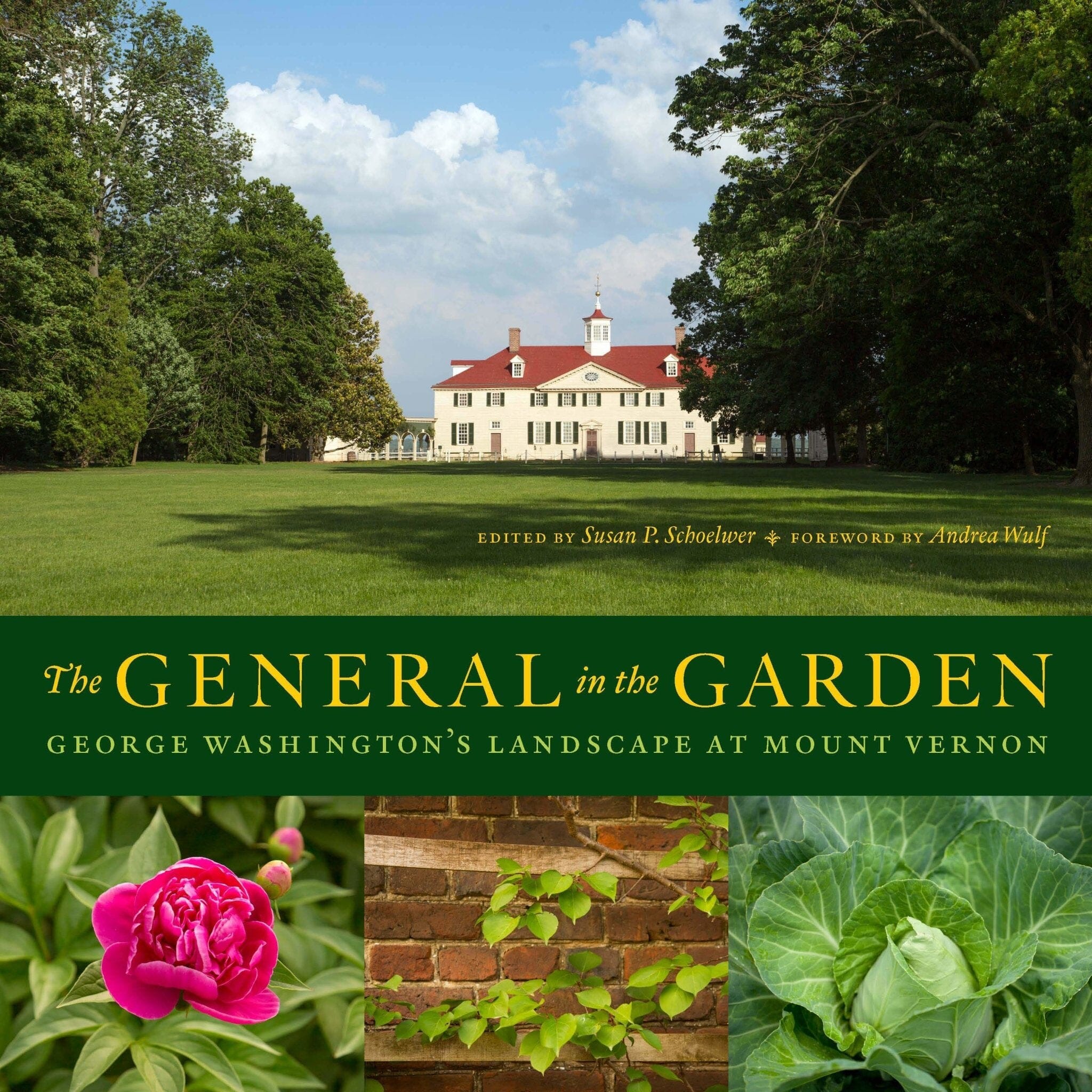

In the ensuing years, Washington expanded Mount Vernon from 2,000 acres into an 8,000-acre property with five farms. He grew a variety of crops, including wheat and corn, bred mules and maintained fruit orchards and a successful fishery. He was deeply interested in farming and continually experimented with new crops and methods of land conservation.

George Washington During the American Revolution

Washington proved to be a better general than military strategist. His strength lay not in his genius on the battlefield but in his ability to keep the struggling colonial army together. His troops were poorly trained and lacked food, ammunition and other supplies (soldiers sometimes even went without shoes in winter). However, Washington was able to give them direction and motivation. His leadership during the winter of 1777-1778 at Valley Forge was a testament to his power to inspire his men to keep going.

By the late 1760s, Washington had experienced firsthand the effects of rising taxes imposed on American colonists by the British and came to believe that it was in the best interests of the colonists to declare independence from England. Washington served as a delegate to the First Continental Congress in 1774 in Philadelphia. By the time the Second Continental Congress convened a year later, the American Revolution had begun in earnest, and Washington was named commander in chief of the Continental Army.

Over the course of the grueling eight-year war, the colonial forces won few battles but consistently held their own against the British. In October 1781, with the aid of the French (who allied themselves with the colonists over their rivals the British), the Continental forces were able to capture British troops under General Charles Cornwallis (1738-1805) in the Battle of Yorktown . This action effectively ended the Revolutionary War and Washington was declared a national hero.

America’s First President

In 1783, with the signing of the Treaty of Paris between Great Britain and the U.S., Washington, believing he had done his duty, gave up his command of the army and returned to Mount Vernon, intent on resuming his life as a gentleman farmer and family man. However, in 1787, he was asked to attend the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia and head the committee to draft the new constitution . His impressive leadership there convinced the delegates that he was by far the most qualified man to become the nation’s first president.

At first, Washington balked. He wanted to, at last, return to a quiet life at home and leave governing the new nation to others. But public opinion was so strong that eventually he gave in. The first presidential election was held on January 7, 1789, and Washington won handily. John Adams (1735-1826), who received the second-largest number of votes, became the nation’s first vice president. The 57-year-old Washington was inaugurated on April 30, 1789, in New York City. Because Washington, D.C. , America’s future capital city wasn’t yet built, he lived in New York and Philadelphia. While in office, he signed a bill establishing a future, permanent U.S. capital along the Potomac River—the city later named Washington, D.C., in his honor.

George Washington Raised Martha’s Children and Grandchildren as His Own

The 'Father of the Nation' stressed education among his family's younger generations and even offered advice on navigating love.

How 22‑Year‑Old George Washington Inadvertently Sparked a World War

The first U.S. president’s celebrated military career actually started out quite poorly, in the French and Indian War.

11 Little‑Known Facts About George Washington

He's America's first president. The icon we all think we know. But in reality, he was a complicated human being.

George Washington’s Accomplishments

The United States was a small nation when Washington took office, consisting of 11 states and approximately 4 million people, and there was no precedent for how the new president should conduct domestic or foreign business. Mindful that his actions would likely determine how future presidents were expected to govern, Washington worked hard to set an example of fairness, prudence and integrity. In foreign matters, he supported cordial relations with other countries but also favored a position of neutrality in foreign conflicts. Domestically, he nominated the first chief justice of the U.S. Supreme Court , John Jay (1745-1829), signed a bill establishing the first national bank, the Bank of the United States , and set up his own presidential cabinet .

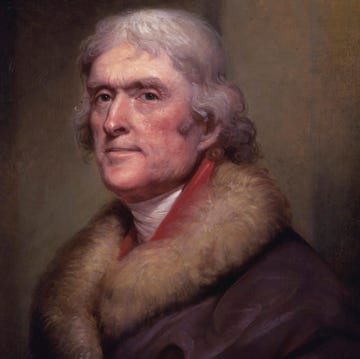

His two most prominent cabinet appointees were Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson (1743-1826) and Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton (1755-1804), two men who disagreed strongly on the role of the federal government. Hamilton favored a strong central government and was part of the Federalist Party , while Jefferson favored stronger states’ rights as part of the Democratic-Republican Party, the forerunner to the Democratic Party . Washington believed that divergent views were critical for the health of the new government, but he was distressed at what he saw as an emerging partisanship.

How George Washington Used Spies to Win the American Revolution

Secret agents, invisible ink, ciphers and codes—the gritty and dangerous underworld of the colonial insurgency

5 Myths About George Washington, Debunked

No, he didn’t really chop down that cherry tree, and his teeth weren’t wooden.

George Washington’s Final Years—And Sudden, Agonizing Death

The Founding Father left the presidency a healthy man, but then died from a sudden illness less than three years later.

George Washington’s presidency was marked by a series of firsts. He signed the first United States copyright law, protecting the copyrights of authors. He also signed the first Thanksgiving proclamation, making November 26 a national day of Thanksgiving for the end of the war for American independence and the successful ratification of the Constitution.

During Washington’s presidency, Congress passed the first federal revenue law, a tax on distilled spirits. In July 1794, farmers in Western Pennsylvania rebelled over the so-called “whiskey tax.” Washington called in over 12,000 militiamen to Pennsylvania to dissolve the Whiskey Rebellion in one of the first major tests of the authority of the national government.

Under Washington’s leadership, the states ratified the Bill of Rights , and five new states entered the union: North Carolina (1789), Rhode Island (1790), Vermont (1791), Kentucky (1792) and Tennessee (1796).

In his second term, Washington issued the proclamation of neutrality to avoid entering the 1793 war between Great Britain and France. But when French minister to the United States Edmond Charles Genet—known to history as “Citizen Genet”—toured the United States, he boldly flaunted the proclamation, attempting to set up American ports as French military bases and gain support for his cause in the Western United States. His meddling caused a stir between Federalists and Democratic-Republicans, widening the rift between parties and making consensus-building more difficult.

In 1795, Washington signed the “Treaty of Amity Commerce and Navigation, between His Britannic Majesty; and The United States of America,” or Jay’s Treaty , so-named for John Jay , who had negotiated it with the government of King George III . It helped the U.S. avoid war with Great Britain, but also rankled certain members of Congress back home and was fiercely opposed by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison . Internationally, it caused a stir among the French, who believed it violated previous treaties between the United States and France.

Washington’s administration signed two other influential international treaties. Pinckney’s Treaty of 1795, also known as the Treaty of San Lorenzo, established friendly relations between the United States and Spain, firming up borders between the U.S. and Spanish territories in North America and opening up the Mississippi to American traders. The Treaty of Tripoli, signed the following year, gave American ships access to Mediterranean shipping lanes in exchange for a yearly tribute to the Pasha of Tripoli.

George Washington’s Retirement to Mount Vernon and Death

In 1796, after two terms as president and declining to serve a third term, Washington finally retired. In Washington’s farewell address , he urged the new nation to maintain the highest standards domestically and to keep involvement with foreign powers to a minimum. The address is still read each February in the U.S. Senate to commemorate Washington’s birthday.

Washington returned to Mount Vernon and devoted his attentions to making the plantation as productive as it had been before he became president. More than four decades of public service had aged him, but he was still a commanding figure. In December 1799, he caught a cold after inspecting his properties in the rain. The cold developed into a throat infection and Washington died on the night of December 14, 1799, at the age of 67. He was entombed at Mount Vernon, which in 1960 was designated a national historic landmark.

Washington left one of the most enduring legacies of any American in history. Known as the “Father of His Country,” his face appears on the U.S. dollar bill and quarter, and dozens of U.S. schools, towns and counties, as well as the state of Washington and the nation’s capital city, are named for him.

HISTORY Vault: Washington

Watch HISTORY's mini-series, 'Washington,' which brings to life the man whose name is known to all, but whose epic story is understood by few.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- Games & Quizzes

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

- Introduction & Top Questions

Childhood and youth

- Early military career

- Marriage and plantation life

- Prerevolutionary politics

- Head of the colonial forces

- The Trenton-Princeton campaign

- At a glance: the Washington presidency

- Postrevolutionary politics

- The Washington administration

- Cabinet of Pres. George Washington

What is George Washington known for?

What political party did george washington belong to, did george washington own slaves, how did george washington die, did george washington chop down his father’s cherry tree.

George Washington

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- United States Senate - Biography of George Washington

- Miller Center - George Washington

- History Central - Biography of George Washington

- George Washington's Mount Vernon - George Washington

- The White House - Biography of George Washington

- Khan Academy - The presidency of George Washington

- Official Site of Kris Kristofferson

- George Washington - Children's Encyclopedia (Ages 8-11)

- George Washington - Student Encyclopedia (Ages 11 and up)

- Table Of Contents

George Washington is often called the “Father of His Country.” He not only served as the first president of the United States , but he also commanded the Continental Army during the American Revolution (1775–83) and presided over the convention that drafted the U.S. Constitution . The U.S. capital is named after Washington—as are many schools, parks, and cities. Today his face appears on the U.S. dollar bill and the quarter.

George Washington did not belong to a political party. He ran as a nonpartisan candidate in the presidential elections of 1789 and 1792 . To this day, Washington is the only U.S. president to have been unanimously elected by the electoral college .

Yes, George Washington owned slaves. Washington was born into a Virginia planter family. After his father’s death in 1743, Washington inherited 10 enslaved people. In 1761 Washington acquired a farmhouse (which he later expanded to a five-farm estate) called Mount Vernon . In 1760, 49 enslaved people lived and worked on the estate; by 1799 that number had increased to over 300. Washington eventually freed the 123 people he owned. In his will he ordered that they be freed “upon the decease of my wife .”

After serving two terms as president, George Washington retired to his estate at Mount Vernon in 1797. Two years into his retirement, Washington caught a cold. The cold developed into a throat infection. Doctors cared for Washington as they thought best—by bleeding him, blistering him, and attempting (unsuccessfully) to give him a gargle of “molasses, vinegar, and butter.” Despite their efforts, Washington died on the night of December 14, 1799.

For years people have shared a story about the first U.S. president involving a hatchet, a cherry tree, and a young Washington who “cannot tell a lie.” The legend attests to George Washington’s honesty, virtue, and piety—that is, if it is true. It is not. The legend was the invention of a 19th-century bookseller named Mason Locke Weems who wanted to present a role model to his American readers . It is one of many legends about Washington.

Recent News

George Washington (born February 22 [February 11, Old Style], 1732, Westmoreland county, Virginia [U.S.]—died December 14, 1799, Mount Vernon, Virginia, U.S.) was an American general and commander in chief of the colonial armies in the American Revolution (1775–83) and subsequently first president of the United States (1789–97).

Washington’s father, Augustine Washington, had gone to school in England, tasted seafaring life, and then settled down to manage his growing Virginia estates. His mother was Mary Ball, whom Augustine, a widower, had married early the previous year. Washington’s paternal lineage had some distinction; an early forebear was described as a “gentleman,” Henry VIII later gave the family lands, and its members held various offices. But family fortunes fell with the Puritan revolution in England, and John Washington, grandfather of Augustine, migrated in 1657 to Virginia. The ancestral home at Sulgrave, Northamptonshire , is maintained as a Washington memorial. Little definite information exists on any of the line until Augustine. He was an energetic, ambitious man who acquired much land, built mills, took an interest in opening iron mines, and sent his two eldest sons to England for schooling. By his first wife, Jane Butler, he had four children. By his second wife, Mary Ball, he had six. Augustine died April 12, 1743.

Little is known of George Washington’s early childhood, spent largely on the Ferry Farm on the Rappahannock River , opposite Fredericksburg , Virginia. Mason L. Weems ’s stories of the hatchet and cherry tree and of young Washington’s repugnance to fighting are apocryphal efforts to fill a manifest gap. He attended school irregularly from his 7th to his 15th year, first with the local church sexton and later with a schoolmaster named Williams. Some of his schoolboy papers survive. He was fairly well trained in practical mathematics—gauging, several types of mensuration, and such trigonometry as was useful in surveying . He studied geography, possibly had a little Latin, and certainly read some of The Spectator and other English classics. The copybook in which he transcribed at 14 a set of moral precepts, or Rules of Civility and Decent Behaviour in Company and Conversation , was carefully preserved. His best training, however, was given him by practical men and outdoor occupations, not by books. He mastered tobacco growing and stock raising, and early in his teens he was sufficiently familiar with surveying to plot the fields about him.

At his father’s death, the 11-year-old boy became the ward of his half brother Lawrence, a man of fine character who gave him wise and affectionate care. Lawrence inherited the beautiful estate of Little Hunting Creek, which had been granted to the original settler, John Washington, and which Augustine had done much since 1738 to develop. Lawrence married Anne (Nancy) Fairfax, daughter of Col. William Fairfax, a cousin and agent of Lord Fairfax and one of the chief proprietors of the region. Lawrence also built a house and named the 2,500-acre (1,000-hectare) holding Mount Vernon in honor of the admiral under whom he had served in the siege of Cartagena . Living there chiefly with Lawrence (though he spent some time near Fredericksburg with his other half brother, Augustine, called Austin), George entered a more spacious and polite world. Anne Fairfax Washington was a woman of charm, grace, and culture; Lawrence had brought from his English school and naval service much knowledge and experience. A valued neighbor and relative, George William Fairfax, whose large estate, Belvoir, was about 4 miles (6 km) distant, and other relatives by marriage, the Carlyles of Alexandria, helped form George’s mind and manners.

The youth turned first to surveying as a profession. Lord Fairfax, a middle-aged bachelor who owned more than 5,000,000 acres (2,000,000 hectares) in northern Virginia and the Shenandoah Valley , came to America in 1746 to live with his cousin George William at Belvoir and to look after his properties. Two years later he sent to the Shenandoah Valley a party to survey and plot his lands to make regular tenants of the squatters moving in from Pennsylvania . With the official surveyor of Prince William county in charge, Washington went along as assistant. The 16-year-old lad kept a disjointed diary of the trip, which shows skill in observation. He describes the discomfort of sleeping under “one thread Bear blanket with double its Weight of Vermin such as Lice Fleas & c”; an encounter with an Indian war party bearing a scalp; the Pennsylvania-German emigrants, “as ignorant a set of people as the Indians they would never speak English but when spoken to they speak all Dutch”; and the serving of roast wild turkey on “a Large Chip,” for “as for dishes we had none.”

The following year (1749), aided by Lord Fairfax, Washington received an appointment as official surveyor of Culpeper county, and for more than two years he was kept almost constantly busy. Surveying not only in Culpeper but also in Frederick and Augusta counties, he made journeys far beyond the Tidewater region into the western wilderness. The experience taught him resourcefulness and endurance and toughened him in both body and mind. Coupled with Lawrence’s ventures in land, it also gave him an interest in western development that endured throughout his life. He was always disposed to speculate in western holdings and to view favorably projects for colonizing the West, and he greatly resented the limitations that the crown in time laid on the westward movement . In 1752 Lord Fairfax determined to take up his final residence in the Shenandoah Valley and settled there in a log hunting lodge, which he called Greenway Court after a Kentish manor of his family’s. There Washington was sometimes entertained and had access to a small library that Fairfax had begun accumulating at Oxford.

The years 1751–52 marked a turning point in Washington’s life, for they placed him in control of Mount Vernon . Lawrence, stricken by tuberculosis , went to Barbados in 1751 for his health, taking George along. From this sole journey beyond the present borders of the United States, Washington returned with the light scars of an attack of smallpox . In July of the next year, Lawrence died, making George executor and residuary heir of his estate should his daughter, Sarah, die without issue. As she died within two months, Washington at age 20 became head of one of the best Virginia estates. He always thought farming the “most delectable” of pursuits. “It is honorable,” he wrote, “it is amusing, and, with superior judgment, it is profitable.” And, of all the spots for farming, he thought Mount Vernon the best. “No estate in United America,” he assured an English correspondent, “is more pleasantly situated than this.” His greatest pride in later days was to be regarded as the first farmer of the land.

He gradually increased the estate until it exceeded 8,000 acres (3,000 hectares). He enlarged the house in 1760 and made further enlargements and improvements on the house and its landscaping in 1784–86. He also tried to keep abreast of the latest scientific advances.

For the next 20 years the main background of Washington’s life was the work and society of Mount Vernon. He gave assiduous attention to the rotation of crops, fertilization of the soil, and the management of livestock. He had to manage the 18 slaves that came with the estate and others he bought later; by 1760 he had paid taxes on 49 slaves—though he strongly disapproved of the institution and hoped for some mode of abolishing it. At the time of his death, more than 300 slaves were housed in the quarters on his property. He had been unwilling to sell slaves lest families be broken up, even though the increase in their numbers placed a burden on him for their upkeep and gave him a larger force of workers than he required, especially after he gave up the cultivation of tobacco. In his will, he bequeathed the slaves in his possession to his wife and ordered that upon her death they be set free, declaring also that the young, the aged, and the infirm among them “shall be comfortably cloathed & fed by my heirs.” Still, this accounted for only about half the slaves on his property. The other half, owned by his wife, were entailed to the Custis estate, so that on her death they were destined to pass to her heirs. However, she freed all the slaves in 1800 after his death.

For diversion Washington was fond of riding, fox hunting, and dancing, of such theatrical performances as he could reach, and of duck hunting and sturgeon fishing. He liked billiards and cards and not only subscribed to racing associations but also ran his own horses in races. In all outdoor pursuits, from wrestling to colt breaking, he excelled. A friend of the 1750s describes him as “straight as an Indian, measuring six feet two inches in his stockings”; as very muscular and broad-shouldered but, though large-boned, weighing only 175 pounds; and as having long arms and legs. His penetrating blue-gray eyes were overhung by heavy brows, his nose was large and straight, and his mouth was large and firmly closed. “His movements and gestures are graceful, his walk majestic, and he is a splendid horseman.” He soon became prominent in community affairs, was an active member and later vestryman of the Episcopal church , and as early as 1755 expressed a desire to stand for the Virginia House of Burgesses .

George Washington

George Washington, a Founding Father of the United States, led the Continental Army to victory in the Revolutionary War and was America’s first president.

(1732-1799)

Who Was George Washington?

George Washington was a Virginia plantation owner who served as a general and commander-in-chief of the colonial armies during the American Revolutionary War, and later became the first president of the United States, serving from 1789 to 1797.

Early Life and Family

Washington was born on February 22, 1732, in Westmoreland County, Virginia. He was the eldest of Augustine and Mary’s six children, all of whom survived into adulthood.

The family lived on Pope's Creek in Westmoreland County, Virginia. They were moderately prosperous members of Virginia's "middling class."

But much of the family’s wealth in England was lost under the Puritan government of Oliver Cromwell . In 1657 Washington’s grandfather, Lawrence Washington, migrated to Virginia. Little information is available about the family in North America until Washington’s father, Augustine, was born in 1694.

Augustine Washington was an ambitious man who acquired land and enslaved people, built mills, and grew tobacco. For a time, he had an interest in opening iron mines. He married his first wife, Jane Butler, and they had three children. Jane died in 1729 and Augustine married Mary Ball in 1731.

Mount Vernon

In 1735, Augustine moved the family up the Potomac River to another Washington family home, Little Hunting Creek Plantation — later renamed Mount Vernon .

They moved again in 1738 to Ferry Farm on the Rappahannock River, opposite Fredericksburg, Virginia, where Washington spent much of his youth.

Childhood and Education

Little is known about Washington's childhood, which fostered many of the fables later biographers manufactured to fill in the gap. Among these are the stories that Washington threw a silver dollar across the Potomac and after chopping down his father's prize cherry tree, he openly confessed to the crime.

It is known that from age seven to 15, Washington was home-schooled and studied with the local church sexton and later a schoolmaster in practical math, geography, Latin and the English classics.

But much of the knowledge he would use the rest of his life was through his acquaintance with woodsmen and the plantation foreman. By his early teens, he had mastered growing tobacco, stock raising and surveying.

Washington’s father died when he was 11 and he became the ward of his half-brother, Lawrence, who gave him a good upbringing. Lawrence had inherited the family's Little Hunting Creek Plantation and married Anne Fairfax, the daughter of Colonel William Fairfax, patriarch of the well-to-do Fairfax family. Under her tutelage, Washington was schooled in the finer aspects of colonial culture.

In 1748, when he was 16, Washington traveled with a surveying party plotting land in Virginia’s western territory. The following year, aided by Lord Fairfax, Washington received an appointment as the official surveyor of Culpeper County.

For two years he was very busy surveying the land in Culpeper, Frederick and Augusta counties. The experience made him resourceful and toughened his body and mind. It also piqued his interest in western land holdings, an interest that endured throughout his life with speculative land purchases and a belief that the future of the nation lay in colonizing the West.

In July 1752, Washington's brother, Lawrence, died of tuberculosis, making him the heir apparent of the Washington lands. Lawrence’s only child, Sarah, died two months later and Washington became the head of one of Virginia's most prominent estates, Mount Vernon. He was 20 years old.

Throughout his life, he would hold farming as one of the most honorable professions and he was most proud of Mount Vernon. Washington would gradually increase his landholdings there to about 8,000 acres

Pre-Revolutionary Military Career

In the early 1750s, France and Britain were at peace. However, the French military had begun occupying much of the Ohio Valley, protecting the King's land interests, particularly fur trappers and French settlers. But the borderlands of this area were unclear and prone to dispute between the two countries.

Washington showed early signs of natural leadership and shortly after Lawrence's death, Virginia's Lieutenant Governor, Robert Dinwiddie, appointed Washington adjutant with a rank of major in the Virginia militia.

French and Indian War

On October 31, 1753, Dinwiddie sent Washington to Fort LeBoeuf, at what is now Waterford, Pennsylvania, to warn the French to remove themselves from land claimed by Britain. The French politely refused and Washington made a hasty ride back to Williamsburg, Virginia's colonial capital.

Dinwiddie sent Washington back with troops and they set up a post at Great Meadows. Washington's small force attacked a French post at Fort Duquesne, killing the commander, Coulon de Jumonville, and nine others and taking the rest prisoners. The French and Indian War had begun.

The French counterattacked and drove Washington and his men back to his post at Great Meadows (later named "Fort Necessity.") After a full day siege, Washington surrendered and was soon released and returned to Williamsburg, promising not to build another fort on the Ohio River.

Though a little embarrassed at being captured, he was grateful to receive the thanks from the House of Burgesses and see his name mentioned in the London gazettes.

Washington was given the honorary rank of colonel and joined British General Edward Braddock's army in Virginia in 1755. The British had devised a plan for a three-prong assault on French forces attacking Fort Duquesne, Fort Niagara and Crown Point.

During the encounter, the French and their Indian allies ambushed Braddock, who was mortally wounded. Washington escaped injury with four bullet holes in his cloak and two horses shot out from under him. Though he fought bravely, he could do little to turn back the rout and led the defeated army back to safety.

Commander of Virginia Troops

In August 1755, Washington was made commander of all Virginia troops at age 23. He was sent to the frontier to patrol and protect nearly 400 miles of border with some 700 ill-disciplined colonial troops and a Virginia colonial legislature unwilling to support him.

It was a frustrating assignment. His health failed in the closing months of 1757 and he was sent home with dysentery.

In 1758, Washington returned to duty on another expedition to capture Fort Duquesne. A friendly-fire incident took place, killing 14 and wounding 26 of Washington's men. However, the British were able to score a major victory, capturing Fort Duquesne and control of the Ohio Valley.

Washington retired from his Virginia regiment in December 1758. His experience during the war was generally frustrating, with key decisions made slowly, poor support from the colonial legislature and poorly trained recruits.

Washington applied for a commission with the British army but was turned down. In 1758, he resigned his commission and returned to Mount Vernon disillusioned. The same year, he entered politics and was elected to Virginia's House of Burgesses.

Martha Washington

A month after leaving the army, Washington married Martha Dandridge Custis, a widow, who was only a few months older than he. Martha brought to the marriage a considerable fortune: an 18,000-acre estate, from which Washington personally acquired 6,000 acres.

With this and land he was granted for his military service, Washington became one of the more wealthy landowners in Virginia. The marriage also brought Martha's two young children, John (Jacky) and Martha (Patsy), ages six and four, respectively.

Washington lavished great affection on both of them, and was heartbroken when Patsy died just before the Revolution. Jacky died during the Revolution, and Washington adopted two of his children.

Enslaved People

During his retirement from the Virginia militia until the start of the Revolution, Washington devoted himself to the care and development of his land holdings, attending the rotation of crops, managing livestock and keeping up with the latest scientific advances.

By the 1790s, Washington kept over 300 enslaved people at Mount Vernon. He was said to dislike the institution of slavery , but accepted the fact that it was legal.

Washington, in his will, made his displeasure with slavery known, as he ordered that all his enslaved people be granted their freedom upon the death of his wife Martha. (This act of generosity, however, applied to fewer than half of Mount Vernon's enslaved people: Those enslaved people owned by the Custis family were given to Martha’s grandchildren after her death.)

Washington loved the landed gentry's life of horseback riding, fox hunts, fishing and cotillions. He worked six days a week, often taking off his coat and performing manual labor with his workers. He was an innovative and responsible landowner, breeding cattle and horses and tending to his fruit orchards.

Much has been made of the fact that Washington used false teeth or dentures for most of his adult life. Indeed, Washington's correspondence to friends and family makes frequent references to aching teeth, inflamed gums and various dental woes.

Washington had one tooth pulled when he was just 24 years old, and by the time of his inauguration in 1789 he had just one natural tooth left. But his false teeth weren't made of wood, as some legends suggest.

Instead, Washington's false teeth were fashioned from human teeth — including teeth from enslaved people and his own pulled teeth — ivory, animal teeth and assorted metals.

Washington's dental problems, according to some historians, probably impacted the shape of his face and may have contributed to his quiet, somber demeanor: During the Constitutional Convention, Washington addressed the gathered dignitaries only once.

American Revolution

Though the British Proclamation Act of 1763 — prohibiting settlement beyond the Alleghenies — irritated Washington and he opposed the Stamp Act of 1765, he did not take a leading role in the growing colonial resistance against the British until the widespread protest of the Townshend Acts in 1767.

His letters of this period indicate he was totally opposed to the colonies declaring independence. However, by 1767, he wasn't opposed to resisting what he believed were fundamental violations by the Crown of the rights of Englishmen.

In 1769, Washington introduced a resolution to the House of Burgesses calling for Virginia to boycott British goods until the Acts were repealed.

After the passage of the Coercive Acts in 1774, Washington chaired a meeting in which the Fairfax Resolves were adopted, calling for the convening of the Continental Congress and the use of armed resistance as a last resort. He was selected as a delegate to the First Continental Congress in March 1775.

Commander-in-Chief of the Continental Army

After the battles of Lexington and Concord in April 1775, the political dispute between Great Britain and her North American colonies escalated into an armed conflict. In May, Washington traveled to the Second Continental Congress in Philadelphia dressed in a military uniform, indicating that he was prepared for war.

On June 15th, he was appointed Major General and Commander-in-Chief of the colonial forces against Great Britain. As was his custom, he did not seek out the office of commander, but he faced no serious competition.

Washington was the best choice for a number of reasons: he had the prestige, military experience and charisma for the job and he had been advising Congress for months.

Another factor was political: The Revolution had started in New England and at the time, they were the only colonies that had directly felt the brunt of British tyranny. Virginia was the largest British colony and New England needed Southern colonial support.

Political considerations and force of personality aside, Washington was not necessarily qualified to wage war on the world's most powerful nation. Washington's training and experience were primarily in frontier warfare involving small numbers of soldiers. He wasn't trained in the open-field style of battle practiced by the commanding British generals.

He also had no practical experience maneuvering large formations of infantry, commanding cavalry or artillery, or maintaining the flow of supplies for thousands of men in the field. But he was courageous and determined and smart enough to keep one step ahead of the enemy.

Washington and his small army did taste victory early in March 1776 by placing artillery above Boston, on Dorchester Heights, forcing the British to withdraw. Washington then moved his troops into New York City. But in June, a new British commander, Sir William Howe , arrived in the Colonies with the largest expeditionary force Britain had ever deployed to date.

Crossing the Delaware

In August 1776, the British army launched an attack and quickly took New York City in the largest battle of the war. Washington's army was routed and suffered the surrender of 2,800 men.

He ordered the remains of his army to retreat into Pennsylvania across the Delaware River. Confident the war would be over in a few months, General Howe wintered his troops at Trenton and Princeton, leaving Washington free to attack at the time and place of his choosing.

On Christmas night, 1776, Washington and his men returned across the Delaware River and attacked unsuspecting Hessian mercenaries at Trenton, forcing their surrender. A few days later, evading a force that had been sent to destroy his army, Washington attacked the British again, this time at Princeton, dealing them a humiliating loss.

Victories and Losses

General Howe's strategy was to capture colonial cities and stop the rebellion at key economic and political centers. He never abandoned the belief that once the Americans were deprived of their major cities, the rebellion would wither.

In the summer of 1777, he mounted an offensive against Philadelphia. Washington moved in his army to defend the city but was defeated at the Battle of Brandywine . Philadelphia fell two weeks later.

In the late summer of 1777, the British army sent a major force, under the command of John Burgoyne, south from Quebec to Saratoga, New York, to split the rebellion between New England and the southern colonies. But the strategy backfired, as Burgoyne became trapped by the American armies led by Horatio Gates and Benedict Arnold at the Battle of Saratoga .

Without support from Howe, who couldn't reach him in time, Burgoyne was forced to surrender his entire 6,200 man army. The victory was a major turning point in the war as it encouraged France to openly ally itself with the American cause for independence.

Through all of this, Washington discovered an important lesson: The political nature of war was just as important as the military one. Washington began to understand that military victories were as important as keeping the resistance alive.

Americans began to believe that they could meet their objective of independence without defeating the British army. Meanwhile, British General Howe clung to the strategy of capturing colonial cities in hopes of smothering the rebellion.

Howe didn't realize that capturing cities like Philadelphia and New York would not unseat colonial power. The Congress would just pack up and meet elsewhere.

Valley Forge

The darkest time for Washington and the Continental Army was during the winter of 1777 at Valley Forge, Pennsylvania. The 11,000-man force went into winter quarters and over the next six months suffered thousands of deaths, mostly from disease. But the army emerged from the winter still intact and in relatively good order.

Realizing their strategy of capturing colonial cities had failed, the British command replaced General Howe with Sir Henry Clinton. The British army evacuated Philadelphia to return to New York City. Washington and his men delivered several quick blows to the moving army, attacking the British flank near Monmouth Courthouse. Though a tactical standoff, the encounter proved Washington's army capable of open field battle.

For the remainder of the war, Washington was content to keep the British confined to New York, although he never totally abandoned the idea of retaking the city. The alliance with France had brought a large French army and a navy fleet.

Washington and his French counterparts decided to let Clinton be and attack British General Charles Cornwallis at Yorktown, Virginia. Facing the combined French and Colonial armies and the French fleet of 29 warships at his back, Cornwallis held out as long as he could, but on October 19, 1781, he surrendered his forces.

Revolutionary War Victory

Washington had no way of knowing the Yorktown victory would bring the war to a close.

The British still had 26,000 troops occupying New York City, Charleston and Savannah, plus a large fleet of warships in the Colonies. By 1782, the French army and navy had departed, the Continental treasury was depleted, and most of his soldiers hadn’t been paid for several years.

A near-mutiny was avoided when Washington convinced Congress to grant a five-year bonus for soldiers in March 1783. By November of that year, the British had evacuated New York City and other cities and the war was essentially over.

The Americans had won their independence. Washington formally bade his troops farewell and on December 23, 1783, he resigned his commission as commander-in-chief of the army and returned to Mount Vernon.

For four years, Washington attempted to fulfill his dream of resuming life as a gentleman farmer and to give his much-neglected Mount Vernon plantation the care and attention it deserved.

The war had been costly to the Washington family with lands neglected, no exports of goods, and the depreciation of paper money. But Washington was able to repair his fortunes with a generous land grant from Congress for his military service and become profitable once again.

Constitutional Convention

In 1787, Washington was again called to the duty of his country. Since independence, the young republic had been struggling under the Articles of Confederation , a structure of government that centered power with the states.

But the states were not unified. They fought among themselves over boundaries and navigation rights and refused to contribute to paying off the nation's war debt. In some instances, state legislatures imposed tyrannical tax policies on their own citizens.

Washington was intensely dismayed at the state of affairs, but only slowly came to the realization that something should be done about it. Perhaps he wasn't sure the time was right so soon after the Revolution to be making major adjustments to the democratic experiment. Or perhaps because he hoped he would not be called upon to serve, he remained noncommittal.

But when Shays' Rebellion erupted in Massachusetts, Washington knew something needed to be done to improve the nation’s government. In 1786, Congress approved a convention to be held in Philadelphia to amend the Articles of Confederation.

At the Constitutional Convention , Washington was unanimously chosen as president. Washington, James Madison and Alexander Hamilton had come to the conclusion that it wasn't amendments that were needed, but a new constitution that would give the national government more authority.

In the end, the Convention produced a plan for government that not only would address the country's current problems, but would endure through time. After the convention adjourned, Washington's reputation and support for the new government were indispensable to the ratification of the new U.S. Constitution .

The opposition was strident, if not organized, with many of America's leading political figures — including Patrick Henry and Sam Adams — condemning the proposed government as a grab for power. Even in Washington's native Virginia, the Constitution was ratified by only one vote.

DOWNLOAD BIOGRAPHY'S GEORGE WASHINGTON FACT CARD

George Washington: Presidency

Still hoping to retire to his beloved Mount Vernon, Washington was once again called upon to serve this country.

During the presidential election of 1789, he received a vote from every elector to the Electoral College, the only president in American history to be elected by unanimous approval. He took the oath of office at Federal Hall in New York City, the capital of the United States at the time.

As the first president, Washington was astutely aware that his presidency would set a precedent for all that would follow. He carefully attended to the responsibilities and duties of his office, remaining vigilant to not emulate any European royal court. To that end, he preferred the title "Mr. President," instead of more imposing names that were suggested.

At first he declined the $25,000 salary Congress offered the office of the presidency, for he was already wealthy and wanted to protect his image as a selfless public servant. However, Congress persuaded him to accept the compensation to avoid giving the impression that only wealthy men could serve as president.

Washington proved to be an able administrator. He surrounded himself with some of the most capable people in the country, appointing Hamilton as Secretary of the Treasury and Thomas Jefferson as Secretary of State. He delegated authority wisely and consulted regularly with his cabinet listening to their advice before making a decision.

Washington established broad-ranging presidential authority, but always with the highest integrity, exercising power with restraint and honesty. In doing so, he set a standard rarely met by his successors, but one that established an ideal by which all are judged.

READ MORE: How George Washington’s Personal and Physical Characteristics Helped Him Win the Presidency

Accomplishments

During his first term, Washington adopted a series of measures proposed by Treasury Secretary Hamilton to reduce the nation's debt and place its finances on sound footing.

His administration also established several peace treaties with Native American tribes and approved a bill establishing the nation's capital in a permanent district along the Potomac River.

Whiskey Rebellion

Then, in 1791, Washington signed a bill authorizing Congress to place a tax on distilled spirits, which stirred protests in rural areas of Pennsylvania.

Quickly, the protests turned into a full-scale defiance of federal law known as the Whiskey Rebellion . Washington invoked the Militia Act of 1792, summoning local militias from several states to put down the rebellion.

Washington personally took command, marching the troops into the areas of rebellion and demonstrating that the federal government would use force, when necessary, to enforce the law. This was also the only time a sitting U.S. president has led troops into battle.

In foreign affairs, Washington took a cautious approach, realizing that the weak young nation could not succumb to Europe's political intrigues. In 1793, France and Great Britain were once again at war.

At the urging of Hamilton, Washington disregarded the U.S. alliance with France and pursued a course of neutrality. In 1794, he sent John Jay to Britain to negotiate a treaty (known as the "Jay Treaty") to secure a peace with Britain and clear up some issues held over from the Revolutionary War.

The action infuriated Jefferson, who supported the French and felt that the U.S. needed to honor its treaty obligations. Washington was able to mobilize public support for the treaty, which proved decisive in securing ratification in the Senate.

Though controversial, the treaty proved beneficial to the United States by removing British forts along the western frontier, establishing a clear boundary between Canada and the United States, and most importantly, delaying a war with Britain and providing over a decade of prosperous trade and development the fledgling country so desperately needed.

Political Parties

All through his two terms as president, Washington was dismayed at the growing partisanship within the government and the nation. The power bestowed on the federal government by the Constitution made for important decisions, and people joined together to influence those decisions. The formation of political parties at first were influenced more by personality than by issues.

As Treasury secretary, Hamilton pushed for a strong national government and an economy built in industry. Secretary of State Jefferson desired to keep government small and center power more at the local level, where citizens' freedom could be better protected. He envisioned an economy based on farming.

Those who followed Hamilton's vision took the name Federalists and people who opposed those ideas and tended to lean toward Jefferson’s view began calling themselves Democratic-Republicans. Washington despised political partisanship, believing that ideological differences should never become institutionalized. He strongly felt that political leaders should be free to debate important issues without being bound by party loyalty.

However, Washington could do little to slow the development of political parties. The ideals promoted by Hamilton and Jefferson produced a two-party system that proved remarkably durable. These opposing viewpoints represented a continuation of the debate over the proper role of government, a debate that began with the conception of the Constitution and continues today.

Washington's administration was not without its critics who questioned what they saw as extravagant conventions in the office of the president. During his two terms, Washington rented the best houses available and was driven in a coach drawn by four horses, with outriders and lackeys in rich uniforms.

After being overwhelmed by callers, he announced that except for the scheduled weekly reception open to all, he would only see people by appointment. Washington entertained lavishly, but in private dinners and receptions at invitation only. He was, by some, accused of conducting himself like a king.

However, ever mindful his presidency would set the precedent for those to follow, he was careful to avoid the trappings of a monarchy. At public ceremonies, he did not appear in a military uniform or the monarchical robes. Instead, he dressed in a black velvet suit with gold buckles and powdered hair, as was the common custom. His reserved manner was more due to inherent reticence than any excessive sense of dignity.

Desiring to return to Mount Vernon and his farming, and feeling the decline of his physical powers with age, Washington refused to yield to the pressures to serve a third term, even though he would probably not have faced any opposition.

By doing this, he was again mindful of the precedent of being the "first president," and chose to establish a peaceful transition of government.

Farewell Address

In the last months of his presidency, Washington felt he needed to give his country one last measure of himself. With the help of Hamilton, he composed his Farewell Address to the American people, which urged his fellow citizens to cherish the Union and avoid partisanship and permanent foreign alliances.

In March 1797, he turned over the government to John Adams and returned to Mount Vernon, determined to live his last years as a simple gentleman farmer. His last official act was to pardon the participants in the Whiskey Rebellion.

Upon returning to Mount Vernon in the spring of 1797, Washington felt a reflective sense of relief and accomplishment. He had left the government in capable hands, at peace, its debts well-managed, and set on a course of prosperity.

He devoted much of his time to tending the farm's operations and management. Although he was perceived to be wealthy, his land holdings were only marginally profitable.

On a cold December day in 1799, Washington spent much of it inspecting the farm on horseback in a driving snowstorm. When he returned home, he hastily ate his supper in his wet clothes and then went to bed.

The next morning, on December 13, he awoke with a severe sore throat and became increasingly hoarse. He retired early, but awoke around 3 a.m. and told Martha that he felt very sick. The illness progressed until he died late in the evening of December 14, 1799.

The news of Washington's death at age 67 spread throughout the country, plunging the nation into a deep mourning. Many towns and cities held mock funerals and presented hundreds of eulogies to honor their fallen hero. When the news of this death reached Europe, the British fleet paid tribute to his memory, and Napoleon ordered ten days of mourning.

Washington could have been a king. Instead, he chose to be a citizen. He set many precedents for the national government and the presidency: The two-term limit in office, only broken once by Franklin D. Roosevelt , was later ensconced in the Constitution's 22nd Amendment.

He crystallized the power of the presidency as a part of the government’s three branches of government , able to exercise authority when necessary, but also accept the checks and balances of power inherent in the system.

He was not only considered a military and revolutionary hero, but a man of great personal integrity, with a deep sense of duty, honor and patriotism. For over 200 years, Washington has been acclaimed as indispensable to the success of the Revolution and the birth of the nation.

But his most important legacy may be that he insisted he was dispensable, asserting that the cause of liberty was larger than any single individual.

Watch "George Washington: Founding Father" on HISTORY Vault

QUICK FACTS

- Name: George Washington

- Birth Year: 1732

- Birth date: February 22, 1732

- Birth State: Virginia

- Birth City: Westmoreland County

- Birth Country: United States

- Gender: Male

- Best Known For: George Washington, a Founding Father of the United States, led the Continental Army to victory in the Revolutionary War and was America’s first president.

- U.S. Politics

- Astrological Sign: Pisces

- Death Year: 1799

- Death date: December 14, 1799

- Death State: Virginia

- Death City: Mount Vernon

- Death Country: United States

We strive for accuracy and fairness.If you see something that doesn't look right, contact us !

CITATION INFORMATION

- Article Title: George Washington Biography

- Author: Biography.com Editors

- Website Name: The Biography.com website

- Url: https://www.biography.com/political-figures/george-washington

- Access Date:

- Publisher: A&E; Television Networks

- Last Updated: September 11, 2020

- Original Published Date: April 3, 2014

- Observe good faith and justice towards all nations; cultivate peace and harmony with all.

- When we assumed the soldier, we did not lay aside the citizen.

- Be courteous to all, but intimate with few.

- [T]he preservation of the sacred fire of liberty, and the destiny of the republican model of government, are justly considered as deeply, perhaps as finally staked, on the experiment entrusted to the hands of the American people.

- We should never despair, our situation before has been unpromising and has changed for the better, so I trust, it will again. If new difficulties arise, we must only put forth new exertions and proportion our efforts to the exigency of the times.

- There can be no greater error than to expect or calculate upon real favors from nation to nation.

- [M]y movements to the chair of government will be accompanied by feelings not unlike those of a culprit who is going to the place of his execution.

- True friendship is a plant of slow growth, and must undergo and withstand the shocks of adversity before it is entitled to the appellation.

- Of all the dispositions and habits which lead to political prosperity, religion and morality are indispensable supports.

- I heard the bullets whistle, and, believe me, there is something charming in the sound.

- Discipline is the soul of an army. It makes small numbers formidable; procures success to the weak, and esteem to all.

- The basis of our political Systems is the right of the people to make and to alter their Constitutions of Government. But the Constitution which at any time exists, 'till changed by an explicit and authentic act of the whole People, is sacredly obligatory upon all.

- I hold the maxim no less applicable to public than to private affairs, that honesty is the best policy.

- The bosom of America is open to receive not only the opulent and respectable stranger, but the oppressed and persecuted of all nations and religions.

Watch Next .css-16toot1:after{background-color:#262626;color:#fff;margin-left:1.8rem;margin-top:1.25rem;width:1.5rem;height:0.063rem;content:'';display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;}

U.S. Presidents

Franklin D. Roosevelt

Thomas Jefferson

A Car Accident Killed Joe Biden’s Wife and Baby

These Are the Major 2024 Presidential Candidates

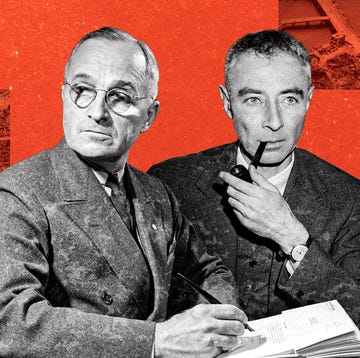

Oppenheimer and Truman Met Once. It Went Badly.

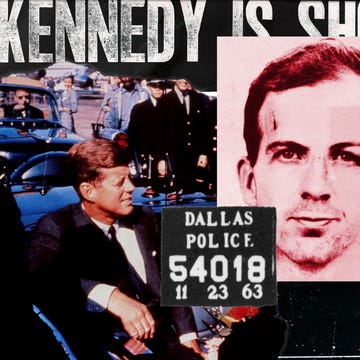

Who Killed JFK? You Won’t Believe Us Anyway

John F. Kennedy

Jimmy Carter

Inside Jimmy and Rosalynn Carter’s 77-Year Love

Abraham Lincoln

Who Is Walt Nauta, the Man Indicted with Trump?

Visiting Sleeping Beauties: Reawakening Fashion?

You must join the virtual exhibition queue when you arrive. If capacity has been reached for the day, the queue will close early.

Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History Essays

George washington: man, myth, monument.

George Washington

Horatio Greenough

Charles Willson Peale

Hiram Powers

George Washington and William Lee (George Washington)

John Trumbull

James Peale

Charles Peale Polk

Giuseppe Ceracchi

Washington Reviewing the Western Army at Fort Cumberland, Maryland

Attributed to Frederick Kemmelmeyer

Gilbert Stuart

The American Star (George Washington)

Frederick Kemmelmeyer

[Girl with Portrait of George Washington]

Southworth and Hawes

Washington Crossing the Delaware

Emanuel Leutze

Rembrandt Peale

Apotheosis of George Washington

Heinrich Weishaupt

George Washington Quilt

Century Vase

Designed by Karl L. H. Müller

Karl L. H. Müller

Carrie Rebora Barratt The American Wing, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

The multiplicity of depictions of George Washington (1732–1799) testifies to his persistence in American life and myth. During his lifetime, his very image, whether presented as a Revolutionary War hero or as chief executive of the United States, exemplified the ideal leader: authoritative, victorious, strong, moral, and compassionate. Over the course of the nineteenth century, American and European popular culture elaborated on Washington’s iconic persona and adapted it to patriotic and sentimental purposes.

Two major bequests to the Metropolitan ensured that the collection would be rich in images of Washington in various media. In 1883, William Henry Huntington bequeathed more than 2,000 American portraits , primarily of Washington, Benjamin Franklin, and the marquis de Lafayette. For much of his life, Huntington was a Paris correspondent for the New York Tribune . An inveterate seeker of Americana at shops and flea markets, he purchased an array of medals, porcelains, textiles, and other works of art while abroad. The second gift to the Museum came in 1924 from Charles Allen Munn, editor and publisher of Scientific American for forty-three years. By the time of his death, Munn had assembled a notable collection of portraits of Washington. Among the highlights of his bequest are portraits by the American artists for whom Washington actually sat, including Gilbert Stuart ( 07.160 ), Charles Willson Peale ( 97.33 ), and John Trumbull ( 24.109.88 ).

General George Washington A gentleman farmer from Virginia, Washington began his military career at the age of twenty, when he was commissioned as a major in the state’s militia; within three years, he had risen through the ranks to be appointed commander in chief of those troops. Twenty years later, in 1775, he was named commander in chief of the Continental Forces of North America, and he led his army to victory over Great Britain. He was admired for his ability to inspire and lead a disparate group of men into battle. After his retirement from service at the war’s end, he was venerated by his contemporaries and by subsequent generations of military men. Washington’s image in uniform, portrayed by so many artists in a variety of media, became a symbol not only of military prowess but also of national unity and American liberty.

President George Washington During Washington’s two terms as president (1789–97), his image was modeled almost exclusively on portraits by Gilbert Stuart (1755–1828), the premier painter of the new nation . Stuart executed three different portraits from life sittings with the president, but it was the so-called Athenaeum portrait that became the most popular. Stuart himself painted at least seventy replicas of it, and, because it was exhibited in the Boston Athenaeum after Stuart’s death, many other artists were able to use it as the basis for their work. Stuart’s portrayal of Washington became so pervasive that, as the artist’s biographer, the critic William Dunlap, put it in 1832, “if George Washington should appear on earth, . . he would be treated as an impostor, when compared to Stuart’s likeness of him, unless he produced his credentials.”

The Myth of George Washington The extraordinary outpouring of emotion after Washington’s death on December 14, 1799, reverberated worldwide, as mourners grieved not merely for the man himself but for the hero he had become and, still more warmly, for the father of the country. Washington’s role in American life had been of long duration and great depth. His image symbolized the power and legitimacy of the newly independent nation, which was still very much in the formative stages during the nineteenth century. His imposing figure as president embodied ideals of honesty, virtue, and patriotism ( 62.256.7 ). Nineteenth-century images of Washington ranged from his godlike apotheosis ( 52.585.66 ) to scenes of his personal life . His home, Mount Vernon , on the Potomac River in northern Virginia, became a shrine to his mythic celebrity. In 1853, the Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association was founded, mostly through the efforts of women, in order to save the historic property and honor Washington’s legacy.

George Washington and the American Centennials In 1876, the United States observed the centennial of its founding, and 1889 marked the 100th anniversary of George Washington’s first inauguration as president. Nearing the turn of the twentieth century , at a time when Americans clamored for reassurance that their leaders were trustworthy and the country secure, both celebrations featured commemorative images of Washington—the epitome of an honorable head of state—in his varied roles as public servant and private individual.

In Philadelphia, the Centennial Exposition of 1876 featured new developments in art, design, and technology from an international group of exhibitors and attracted more than 8 million visitors. Washington’s portrait on plates ( 69.194.1 ), handkerchiefs ( 1985.347 ), glassware, and prints provided a nostalgic foil to burgeoning technological developments and made the country’s progress seem a natural continuum, from the American Revolution to the Industrial Revolution.

In 1889, grand celebrations were mounted in honor of the centennial of Washington’s inauguration. New York City officials erected a great arch at the foot of Fifth Avenue (in Washington Square), held a parade, launched a naval flotilla, and reenacted the swearing-in ceremony that had taken place in New York when it was briefly the nation’s capital. The Metropolitan Opera House hosted a gala ball and mounted an exhibition of Washington’s personal belongings and related memorabilia—pieces of history that established an authentic link to the country’s past and gave promise for the future.

Barratt, Carrie Rebora. “George Washington: Man, Myth, Monument.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History . New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/wash/hd_wash.htm (May 2009)

Further Reading

Barratt, Carrie Rebora, and Ellen G. Miles. Gilbert Stuart . Exhibition catalogue. New York: Yale University Press, 2004. See on MetPublications

Ellis, Joseph J. His Excellency: George Washington . New York: Knopf, 2004.

Fischer, David Hackett. Washington's Crossing . Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004.

Schwartz, Barry. George Washington: The Making of an American Symbol . New York: Free Press, 1987.

Additional Essays by Carrie Rebora Barratt

- Barratt, Carrie Rebora. “ Gilbert Stuart (1755–1828) .” (October 2003)

- Barratt, Carrie Rebora. “ American Portrait Miniatures of the Nineteenth Century .” (October 2004)

- Barratt, Carrie Rebora. “ John Singleton Copley (1738–1815) .” (October 2003)

- Barratt, Carrie Rebora. “ American Portrait Miniatures of the Eighteenth Century .” (October 2003)

- Barratt, Carrie Rebora. “ American Scenes of Everyday Life, 1840–1910 .” (September 2009)

- Barratt, Carrie Rebora. “ Nineteenth-Century American Folk Art .” (October 2004)

- Barratt, Carrie Rebora. “ Students of Benjamin West (1738–1820) .” (October 2004)

- Barratt, Carrie Rebora. “ Thomas Sully (1783–1872) and Queen Victoria .” (October 2004)

Related Essays

- American Portrait Miniatures of the Eighteenth Century

- Art and Identity in the British North American Colonies, 1700–1776

- Art and Society of the New Republic, 1776–1800

- Gilbert Stuart (1755–1828)

- Hiram Powers (1805–1873)

- American Federal-Era Period Rooms

- American Furniture, 1730–1790: Queen Anne and Chippendale Styles

- American Georgian Interiors (Mid-Eighteenth-Century Period Rooms)

- American Neoclassical Sculptors Abroad

- American Portrait Miniatures of the Nineteenth Century

- American Revival Styles, 1840–76

- American Scenes of Everyday Life, 1840–1910

- American Silver Vessels for Wine, Beer, and Punch

- Architecture, Furniture, and Silver from Colonial Dutch America

- Augustus Saint-Gaudens (1848–1907)

- Coffee, Tea, and Chocolate in Early Colonial America

- Duncan Phyfe (1770–1854) and Charles-Honoré Lannuier (1779–1819)

- English Ornament Prints and Furniture Books in Eighteenth-Century America

- Frederick William MacMonnies (1863–1937)

- Henry Kirke Brown (1814–1886), John Quincy Adams Ward (1830–1910), and Realism in American Sculpture

- John Singleton Copley (1738–1815)

- John Townsend (1733–1809)

- Paul Revere, Jr. (1734–1818)

- Students of Benjamin West (1738–1820)

List of Rulers

- Presidents of the United States of America

- The United States and Canada, 1800–1900 A.D.

- The United States, 1600–1800 A.D.

- 18th Century A.D.

- 19th Century A.D.

- American Art

- American Decorative Arts

- Architectural Element

- Colonial American Art

- Nationalism

- North America

- United States

Artist or Maker

- Ceracchi, Giuseppe

- Greenough, Horatio

- Hawes, Josiah Johnson

- Kemmelmeyer, Frederick

- Leutze, Emanuel Gottlieb

- Moore, Samuel

- Müller, Karl L.H.

- Peale, Charles Willson

- Peale, James

- Peale, Rembrandt

- Polk, Charles Peale

- Powers, Hiram

- Southworth, Albert Sands

- Stuart, Gilbert

- Trumbull, John

- Union Porcelain Works

- Weishaupt, H.

Online Features

- Connections: “Smile” by Kathy Galitz

- Connections: “The Ideal Man” by Nadine Orenstein

Plan Your Visit

- Things to Do

- Where to Eat

- Hours & Directions

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Accessibility

- Washington, D.C. Metro Area

- Guest Policies

- Historic Area

- Distillery & Gristmill

- Virtual Tour

- George Washington

- French & Indian War

- Revolutionary War

- Constitution

- First President

- Martha Washington

- Native Americans

- Back to Main menu

Preservation

- Collections

- Archaeology

- Architecture

- The Mount Vernon Ladies' Association

- Restoration Projects

- Preserving the View

- Preservation Timeline

- Primary Source Collections

- Secondary Sources

- Educational Events

- Interactive Tools

- Videos and Podcasts

- Hands on History at Home

Washington Library

- Catalogs and Digital Resources

- Research Fellowships

- The Papers of George Washington

- Library Events & Programs

- Leadership Institute

- Center for Digital History

- George Washington Prize

- About the Library

Estate Hours

9 a.m. to 5 p.m.

u_turn_left Directions & Parking

10 Things You Really Ought to Know about George Washington

1. washington was mostly self-educated.

When George Washington’s father died in 1743, there was little money left to support the formal education of 11-year-old George.

Washington’s formal schooling ended by the time he was 15, but his pursuit of knowledge continued throughout his life. He read to become a better soldier, farmer, and president; he corresponded with authors and friends in America and Europe; and he exchanged ideas that fed the ongoing agricultural, social, and political revolutions of his day.

Rules of Civility Washington the Reader

Washington portrayed as a young, self-motivated surveyor. (MVLA)

2. He was fearless in battle

With men and officers being shot down all around him, George Washington rode forward to take charge of the collapsing lines at the Battle of the Monongahela on July 9, 1755.

While riding along the ranks looking to steady the men, Washington had two horses shot out from under him and four bullet holes shot through his coat.

At the Battle of Princeton (January 3, 1777), Washington rode forward on his white charger as he led his soldiers in a successful counter-attack against the British. At one point Washington was no more than 30 yards from the British line and was an easy target.

Despite the widespread fears that he would be shot down at any moment, Washington was heard to say to his troops, “Parade with me my fine fellows, we will have them soon!”

French & Indian War 10 Facts about the Battle of Princeton

George Washington at the Battle of Monmouth by Emanuel Leutze (1857), from the collection of the Monmouth County Historical Association.

3. Washington’s bold actions saved the American Revolution, twice

After a series of stinging defeats in New York and New Jersey, the Continental Army and the patriot cause seemed near extinction by December 1776.

Most generals would have slipped away to the safety of winter quarters, but Gen. Washington had an entirely different plan in mind.

His bold counterstroke across the ice-choked Delaware River on December 25, 1776, led to three successive battlefield victories and a stunning strategic reversal which bolstered American morale and saved the new nation.

With the Revolution once again on the brink of defeat in early 1781, Washington embarked on a risky march south to surround and attack Lord Cornwallis’ British army at Yorktown, Virginia . Washington’s victory at Yorktown in October 1781 proved to be the decisive battle of the war.

Video: Crossing the Delaware Video: Yorktown Revolutionary War

Washington and Lafayette at Valley Forge in the winter of 1777-78. Library of Congress.

4. He never abused power

While Washington is best known for the positions he held, both as a general and president, it is his willingness to surrender power that may be his most important legacy.

On December 23, 1783, Washington strode into the Maryland State House in Annapolis and surrendered his military commission to Congress—thereby affirming the principle of civilian control of the military.

When King George III heard that Washington would surrender his commission, he reportedly said that if "He did [this] He would be the greatest man in the world."

As president, in a time when there were no term limits and many would have supported a lifetime role, Washington stepped down after the end of his second term—setting an important precedent that lasted until the middle of the 20th century.

Lessons in Leadership

“General George Washington Resigning His Commission to Congress As Commander in Chief of the Army at Annapolis, Maryland, December 23d, 1783,” John Trumbull, oil on canvas, Commissioned 1817, purchased 1824. Image courtesy of Architect of the Capitol.

5. Washington owned more than 50,000 acres and was an ardent promoter of westward expansion

Washington owned more than 50,000 acres in the western portions of Virginia and what is now West Virginia, as well as in Maryland, Pennsylvania, New York, Kentucky, and the Ohio country.

Long before Lewis and Clark set forth on their journey westward, Washington had a keen appreciation for how an expansion into western territory would not only enrich the new nation, but also help to better knit the country together.

By linking the headwaters of the west-flowing Ohio and the east-flowing Potomac, Washington envisioned a continental transportation system that would allow the future produce of the Ohio Valley to flow easily to Atlantic ports.

Even Washington’s choice to place the national capital along the banks of the Potomac was designed to reinforce this westward-looking view.

Washington and the West Washington’s World Map

George Washington, depicted as a young surveyor. Painting by Henry Hintermeister, 1948. Wikimedia.

6. Washington loved parties and was an excellent dancer

Many see Washington as a stoic and unapproachable figure, but in reality he was a man who loved entertainment and the company of others.

There are many accounts of his dancing late into the night at various balls, cotillions, and parties. He loved theater and attended plays of all sorts throughout his life.

And during a time where stiff 18th-century formality pervaded relations between the sexes, Washington was known as an interested and engaged communicator with women.

DANCING WITH GENERAL WASHINGTON A Love Letter