- Recent Reviews

- New Releases

- Five Star Reads

- Best of the Years

- Children’s (MG) SFF

- Young Adult (YA) FF

- Comics Reviews

- How to Read Comics

- Short Fiction

- Stand-Alone SFF

- British Science Fiction Award

- Locus Award

- Mythopoeic Award

- Nebula Award

- Shirley Jackson Award

- Theodore Sturgeon Award

- World Fantasy Award

- SFF on Film & TV

- The FanLit Reviewers

- Our rating system

- Contact / Donate / FAQ

- Apply to join our staff

- The FanLit Stacks

Select Page

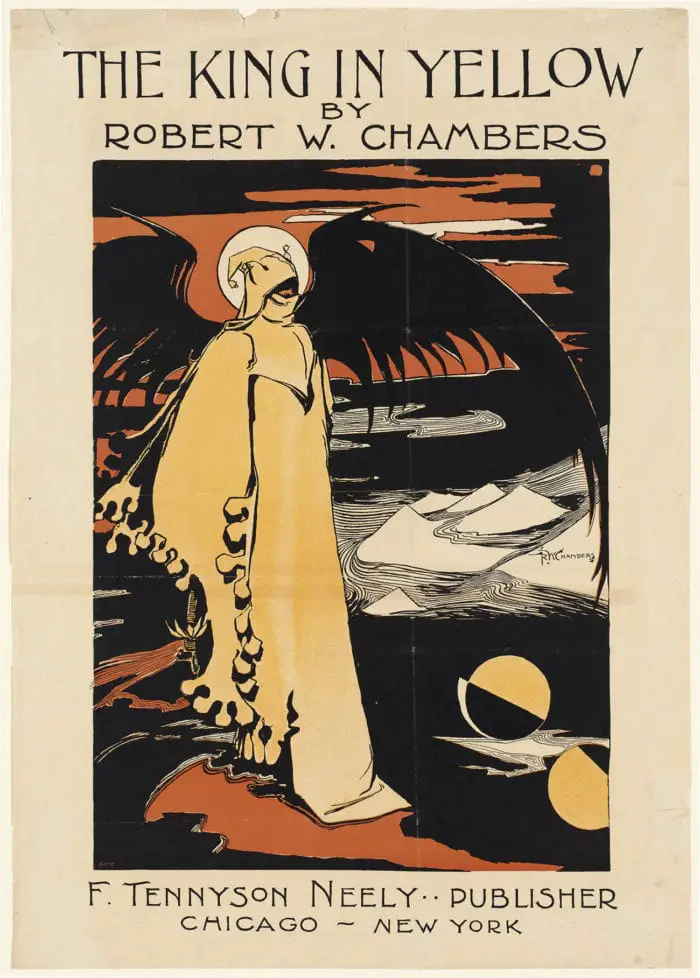

The King in Yellow: Weird stories that inspired H.P. Lovecraft

Posted by Marion Deeds and Jason Golomb ´s rating: 4 | Robert W. Chambers | Horror , Short Fiction , Stand-Alone | SFF Reviews | 7 comments |

… It is well known how the book spread like an infectious disease, from city to city, from continent to continent, barred out here, confiscated there, denounced by Press and pulpit, censured by even the most advanced of literary anarchists… It could not be judged by any known standard, yet, although it was acknowledged that the supreme note of art had been struck in The King in Yellow, all felt that human nature could not bear the strain, nor thrive on the words in which the essence of purest poison lurked.

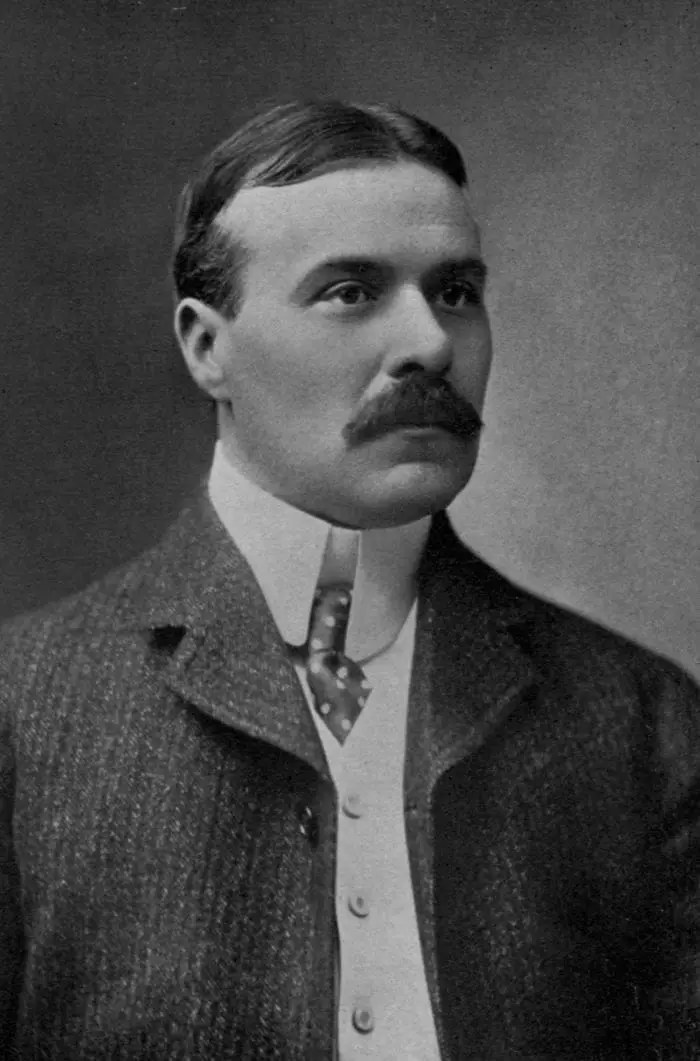

Robert W. Chambers was an American writer who was born in 1865. He studied art in Paris for a time, returning to the U.S. to be an artist and illustrator. He sold some drawings, then switched tracks and began writing. His first novel was called In the Quarter and was a partially biographical story set in Paris’s Latin Quarter, following a group of artists and art students. In 1895, he published a collection of stories called The King in Yellow . In the first four stories, some character has an encounter with a mysterious play also called The King in Yellow . People who read The King in Yellow either go mad or experience some dire, supernatural misfortune.

These four stories and the idea of a book/play that infects its readers with madness later inspired writers like H.P. Lovecraft , Clark Ashton Smith and Lin Carter , and contemporary writers like Karl Edward Wagner. Chambers could write, and his strength was description, probably because he was bringing a painter’s eye to the scenes he imagined. He also had an ear for dialogue. The “yellow king” stories are good examples for their time. Lovecraft, in a letter to Clark Ashton Smith, compared Chambers to “fallen Titans,” saying, “He has the right brain and education but is wholly out of the habit of using them.” I think I detect a bit of envy in that sentence, though.

99c Kindle version

The four “yellow king” stories take place in either Paris or New York. In “The Repairer of Reputations,” Hildred Castaigne, our narrator, describes a futuristic 1920s New York (remember that the story was published in 1895). The Imperial Dynasty of America is isolationist and gloriously martial, with cantering companies of cavalry and beautiful white warships at anchor in the harbor. Hildred is a friend of a strange man named Mr. Wilde; Wilde and Castaigne are both servants of the King in Yellow. That king has promised Hildred that once he and his minions enter this plane, Hildred will be crowned king, subject only to the yellow king himself. One thing stands in Hildred’s way: Louis, his cousin and rightful heir to the crown. Chambers does a great job of introducing menace into this story from early on, when Hildred ruminates on what he will do to the doctor who had him shut up in an institution for a time following Hildred’s fall from a horse. The descriptions and imagination here are astounding; Wilde, with his cropped ears and his devil-cat; Hildred’s elaborate time-locked safe that holds his gold and diamond crown, a token from the yellow king, are beautiful strange images that stay with you. When Chambers begins to shred the illusion, he does it very well, especially from a first-person perspective. It’s a good use of an unreliable narrator.

The disfigured “repairer of reputations” can’t be named Wilde by coincidence. The idea of a “yellow” book that drives people mad may not be coincidental either. In 1894, the literary quarterly The Yellow Book was published for the first time. The color of the cover reflected infamous “French novels.” Audrey Beardsley was one of the illustrators for the periodical, which was abused by critics and seen as decadent and deviant by large swathes of the public (“from the Press to the pulpit?”). When, in April, 1894, Oscar Wilde was arrested, reporters said he was carrying a “yellow book.” Soon, this translated into “the Yellow Book ” even though Wilde had said publicly that he hated the journal. Wilde also has a character in The Portrait of Dorian Grey read a “yellow book” as an escape after a loved one has committed suicide. It’s hard to believe these correspondences are all coincidental.

“The Repairer of Reputations” is the one story that details the most about The King in Yellow and his city, Carcosa, but we will hear about Carcosa again.

“The Mask” opens with a scene from the play The King in Yellow , introducing the characters of Camilla, Cassilda and The Stranger. This snippet of dialogue seems to echo Edgar Allen Poe’s “Masque of the Red Death.” The story moves in another direction, though, following a tragic love triangle that includes our narrator, Alec, his sculptor friend Boris, and Boris’s beautiful wife Genevieve. This story was not Chambers’s strongest, although once again he delivers some lush, gorgeous descriptions. Boris has discovered or invented a clear liquid that will petrify anything organic that it touches, creating a beautiful, perfect sculpture that looks like a cross between opal and the finest marble. For reasons that aren’t clear, Boris puts a pool of this deadly stuff in the middle of a room in his house he is refurbishing. (Can you say, “An accident waiting to happen?”) The story then spends time showing us that Alec once read part of The King in Yellow . He put it aside, but it was too late. Of course, Alec is hopelessly in love with Genevieve, and Genevieve loves both men, and several people get sick and babble inappropriate things while running high fevers. Chambers has to go way out on a limb to get a happy ending, and a fairy tale one at that. The tone of the story is tragic all the way through and the last paragraph really reads like a sudden change in direction, and a bad one.

“The Court of the Dragon” was my favorite of this set. A nameless first-person narrator relates his experience at church, where the organ music, for the first time ever, is disturbing him. He sees the organist, and that person flashes him a look of intense hatred. Our character is startled and frightened, and flees the church, intending to return home to his apartment in the Court of the Dragon. To his horror he is followed by the organist, trapped in the court, and then — wakes up to discover he has dozed off during the services. Again, the descriptions Chambers uses, from a mass of flowers in the market (the first flowers spotted are yellow jonquils) to the description of the court, are glorious. And of course, the story relies on a twist ending. In this story, for the first time, we catch of glimpse of “the towers of Carcosa.”

Carcosa was not original to Chambers; he seems to have used the magpie-factor all good writers employ and stolen from the best, borrowing the name Carcosa and the idea of a city from a short story by Ambrose Pierce, “ An Inhabitant of Carcosa ” published in 1891. (The site is free but donations are appreciated.) Pierce is less interested in the city than in the main character’s journey, and an “Ozymandias”-like exploration of the power of time, but Chambers makes the city of Carcosa his own. “The Court of the Dragon” also reveals some less-than-enlightened attitudes of the author, as he describes the street level of the court is the home of second hand dealers and iron workers, then says, “All day long the place rings with the clank of hammers and the clang of metal bars. Unsavoury as it is below, there is cheerfulness, and comfort, and honest, hard work above.” Presumably anyone who works with their hands (unless he’s an artist) is dishonest by definition.

“The Yellow Sign” is a conventional horror story that shares its roots with dozens of scary-campfire-tales. Scott is a painter in New York. He sees a disgusting-looking man, who reminds him of a “coffin worm” on the stoop of his building. Distracted by this man, Scott ruins the portrait he is working on, and his model, Tessie, scolds him. When Tessie looks out the window and sees the worm-like man, she reacts with horror and tells Scott about a dream she had of a hearse and a coffin. Scott laughs it off, but has a similar dream the next night. The story shifts its focus to the growing relationship between Tessie and Scott. Scott buys her a small cross, and she gives him a pendant she found, with a yellow sign on it. The origins of the worm-like man, who has not left, become more frightening, as Scott gathers information from his concierge and others in the building. When an accident leaves him unable to paint, Tessie finds a book to read to him, and somehow, it is The King in Yellow .

I was dumfounded. Who had placed it here? How came it in my rooms? I had long ago decided that I should never open that book, and nothing on earth could have persuaded me to buy it… If I ever had had any curiosity to read it, the awful tragedy of young Castaigne, whom I knew, prevented me from exploring its wicked pages…

Several of the remaining stories in the book have supernatural elements. In “The Demoiselle D’ys” an American on a walking tour in Breton gets lost, encounters an unusual young woman, and accompanies her to her castle. Anyone who has ever read a “fairy” story knows where this one is going, but again, lovely descriptions and Chambers’s use of 15 th century language make it a treat to read.

I consider “The Prophet’s Paradise,” a series of linked vignettes connected by ending lines, to be almost experimental. It was an interesting read.

In “The Street of the Four Winds” a lonely artist, Severn, adopts a cat he finds on his threshold. The white cat is not beautiful; it is starving and has lost some hair but we see the beauty in it as it begins to trust Severn. Severn pines for his lost love, Sylvia. Because he is an honorable man, he asks around about the cat, and soon finds that a woman who lives in the same building once had a white cat. Then he discovers that the cat has a jeweled garter buckled around its neck. The story progresses to a haunting ending, but it is more sad than macabre. I loved the writing here and the evocation of the once-glorious, now shabby building, but it is Severn’s loneliness and his friendship with the cat that makes this story still work today.

“The Street of the First Shell” once again visits a group of male art students and the women in their lives, but it is instructive because it takes place during the 1870 siege of Paris. This is something I knew about only in the abstract. Chambers creates a sense of dread as shells whistle down around the Latin Quarter, and the characters try to maintain their lives. This story and two others, “Our Lady of the Fields” and “Rue Barree,” made me roll my eyes at the chivalrous, innocent American male heroes, the pure or not-so-pure maidens, and the eternal moment of doomed love — but that eye-rolling is a direct result in the difference in values and mores between 1895 and 2015. I can see in all three of these forbidden-love tales just why Chambers would make most of his writing money from “shopgirl romances;” his honeyed prose, his sentimentality and his eagerness to dodge subtlety at any cost (the protagonist and the kept-woman he is infatuated with in “Our Lady of the Fields” meet on a bench underneath a statue of Eros) must lend themselves perfectly to star-crossed lovers, stolen kisses, secrets revealed and happy endings.

If you like weird horror, you’re a Lovecraft fan, or you have an interest in tales where the terror is internal and the characters can’t quite trust their own senses, then Chambers is worth reading for his own sake. Those interested in the history and influence of horror and supernatural fiction definitely owe it to themselves to put The King in Yellow on their bookshelves.

~Marion Deeds

Stephen King has embedded the genetics of Weird Fiction in some of his most famous work. One need look no further than It , From a Buick 8 , and the recent King bestseller Revival to find the massive, vague, ill defined, but horror-imbued Lovecraftian “otherness.” Williams precedes Lovecraft and helped the genre gain a foothold of acceptance.

As Marion highlights, only four of Williams’ 10 stories (though it’s really 9 stories and one meandering poem) incorporate the myth of the “The King in Yellow,” a fictional play that turns every reader or viewer mad. “The Repairer of Reputations” is probably the strongest work, in part because it’s the first introduction to “The King in Yellow.” On page two:

I pray God will curse the writer, as the writer has cursed the world with this beautiful, stupendous creation terrible in its simplicity, irresistible in its truth – a world which now trembles before the King in Yellow.

“The Mask,” “In the Court of the Dragon,” and “The Yellow Sign” all incorporate elements of the core Yellow mythology. Following “Repairer” and “The Demoiselle D’ys,” which is a touching time-travel romance, the stories grow progressively more confusing, and sometimes incomprehensible.

The language was as one might expect from literature of 1895. I was prepared for the convoluted sentence structure but there were instances where I had to read Williams’ dialogue multiple times in the hopes of deciphering where he was trying to lead me with his plot. In most cases I realized I didn’t care.

If you’re a fan of weird fiction, I’d absolutely recommend reading the stories tied to The King in Yellow. I’d equally and more sternly recommend that you not bother with the rest.

~Jason Golomb

Marion Deeds, with us since March, 2011, is the author of the fantasy novella ALUMINUM LEAVES. Her short fiction has appeared in the anthologies BEYOND THE STARS, THE WAND THAT ROCKS THE CRADLE, STRANGE CALIFORNIA, and in Podcastle, The Noyo River Review, Daily Science Fiction and Flash Fiction Online. She’s retired from 35 years in county government, and spends some of her free time volunteering at a second-hand bookstore in her home town.

JASON GOLOMB graduated with a degree in Communications from Boston University in 1992, and an M.B.A. from Marymount University in 2005. His passion for ice hockey led to jobs in minor league hockey in Baltimore and Fort Worth, before he returned to his home in the D.C. metro area where he worked for America Online. His next step was National Geographic, which led to an obsession with all things Inca, Aztec and Ancient Rome. But his first loves remain SciFi and Horror, balanced with a healthy dose of Historical Fiction.

March 3rd, 2017. Marion Deeds and Jason Golomb ´s rating: 4 | Robert W. Chambers | Horror , Short Fiction , Stand-Alone | SFF Reviews | 7 comments |

I’ve always wondered about this book, esp. since I found out that it was the inspiration for the first season of True Detective.

I haven’t watched it but a friend of mine who has said the references to this book are well done.

After reading your review, I went and found a copy of The King in Yellow via Amazon and immediately downloaded it. Thanks for helping me find another addition to my October creepy reading list, Marion!

This book is also free on Project Gutenberg, if you want to save the 99 cents Amazon charges. :)

Terrific review. I love the whole Lovecraftian-style mythos. And also find the play-makes-you-crazy fascinating. The whole movie-subgenre of tv/videos turning people mad like “The Ring” is terrific but would’ve had no idea it actually goes back to the 1800s.

I thought of The Ring, too. I think it’s a nice way of making literal the power of story-telling. A book (or a play, or a movie) really can change how you see the world. And maybe sometimes that change isn’t good.

Chambers The King in Yellow is indeed a little gem and, as noted,has become something of a cult classic. Just as Chambers influenced Lovecraft, so too was he influenced by the weird fiction of Ambrose Bierce, as demonstrated by his referencing the mythical city of Carcossa, mentioned in one of Bierce’s classic short stories.

Leave a reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Don't subscribe All new comments Replies to my comments Notify me of followup comments via e-mail. If you prefer, you can click here to subscribe without commenting .

Subscribe to all posts:

You can subscribe to our new posts via email, email digest, browser notifications, rss, etc. you can filter by tag, keyword, post author, etc. we won't share your email address with anyone and you can easily unsubscribe at any time., get notified about giveaways:, enter your email address to get notifications about giveaways only. we won't share your address with anyone and you can easily unsubscribe at any time., support fanlit.

- KINDLE DAILY SFF DEALS

- KINDLE $3.99 OR LESS MONTHLY DEALS

Recent Discussion:

Troy, 100% agreed. Sadly the BBC adaptation is also confused about this. They seem to think Orciny is some kind…

Hey Marion! The weather is the *same* in Ul Qoma and Beszel in the novel. They even have a recurring…

Narrated by Samuel L. Jackson....

On a more serious note, well, shoot. I was torn between reading James by Percival Everett, or rereading Hard-Boiled Universe…

"Goodnight F***ing Moon?" Hahahahahahahaha!

Subscribe to all comments:

Switch to the light mode that's kinder on your eyes at day time.

Switch to the dark mode that's kinder on your eyes at night time.

The King in Yellow: An Overlooked Classic

The King in Yellow is a masterful collection of stories composed by Robert W. Chambers and first published in 1895. It comprises ten stories of varying lengths and levels of fright, ranging from short and intense to highly disturbing slow burns.

The premise revolves around a play published within the story of the book itself, also entitled The King in Yellow , that is so sublimely and terrifyingly profound that it drives its readers insane. What’s more…it is repeatedly hinted throughout the collection that the embodied source of this insanity is mystifyingly real and, let’s just say, not from around here.

If you’ve never heard of Chambers before, there’s a reason.

25 years before the great literary mastermind H.P. Lovecraft was born in Rhode Island, Chambers was born in New York. Though eminently talented, he was in the unfortunate position of having absolutely no idea what he wanted. Starting as an artist, he moved to Paris, where his work was featured in the Paris Salon and purchased by several magazines [1].

By all accounts, he was doing better than he had any right to expect when he inexplicably abandoned painting for writing horror. As it happened, he was surprisingly good, which only made it weirder when he recklessly dropped scary stories for eye-rolling romance novels. Lastly, and less bizarrely, Chambers gave up writing romance for historical fiction when the First World War began. At the time of his death in December 1933, he left behind a legacy much like a bag of trail snacks: tasty but mixed [2].

Of him, Lovecraft remarked,

Chambers is like Rupert Hughes and a few other fallen Titans—equipped with the right brains and education but wholly out of the habit of using them. [3]

Despite the rough treatment, it’s only thanks to Lovecraft that we are even speaking of Chambers at all. During his days of writing horror, he captured the attention of Lovecraft and his ilk with a splendid collection of stories entitled The King in Yellow .

Thoroughly impressed, he included The King in Yellow in Supernatural Horror in Literature, Lovecraft’s erudite examination of the genre [4]. In fact, there’s a good argument that Lovecraft’s signature style of slow and nebulous narration is directly inspired by Chambers. Going even further, Lovecraft partially incorporated The King in Yellow into his own Cthulhu mythos by way of several references. Without those inclusions, it is entirely possible that The King in Yellow would not have survived the ravages of time.

Fortunately for us, it has.

What follows is a prodigious literary danse macabre across several shadow-laden locations and tragic characters. The first four stories directly connect to each other in both theme and character, while the remaining six are independent.

Each story takes place within the same world and period of time, and though they feature different locations and characters, they all connect. Anyone familiar with the narrative style of the recent Marvel movies will understand this perfectly. A seemingly random name mentioned offhand by a character in the first story may be the protagonist of the third. The distant hometown of the protagonist in the second story may well be the main setting of the fourth, and so on. As such, The King in Yellow improves with repeated reads as one comes to see the grisly intricacy with which Chambers weaves his web.

The King in Yellow begins with “The Repairer of Reputations,” the longest story in the collection. This is partly due to the fact that it begins with a solid three pages of backstory establishing the time period for the rest of the book. Alongside the worldbuilding, “The Repairer of Reputations” opens with an excerpt from the King in Yellow play, giving us a peek into the nightmare pages that will torment us during the upcoming chapters.

“The Repairer of Reputations” follows the story of Hildred Castaigne, a young and semi-aristocratic man whose personality has been recently altered by an ill-timed head injury. Hildred is the very definition of the unreliable narrator archetype, and Chambers was one of the very first to employ it. Sometime shortly after his injury, Hildred reads a copy of The King in Yellow and descends into both lunacy and staggering neuroticism. His immediate associates are then cast into a world of psychotic danger as Hildred grows ever more violent and delusional. For its time, The Repairer of Reputations was starkly experimental and avant-garde. It still holds up very well today and is a brilliant opening note for the collection.

The second story within The King in Yellow is entitled “The Mask ,” and whereas “The Repairer of Reputations” is long and gritty, this one is short and dream-like. It also begins with an excerpt from the King in Yellow play and features a man named Alec as the protagonist. Alec is friends with a young sculptor by the name of Boris and two other Paris-dwelling bohemians. Boris however is certainly not the average sculptor and is something of an alchemist, too. The four friends end up being exposed to The King in Yellow over the course of the story, and delirium-induced tragedy ensues. That being said, the ending of “The Mask” is actually quite positive for a horror story, so I won’t dare spoil it here.

Next is “In the Court of the Dragon ,” the shortest and most intense of the first four stories. This time our narrator has no name and is merely described as something of a failed artist living in France. Our new friend is busy attending church when the story begins, though we soon learn he is there to seek comfort from unseen woes. Turns out, our protagonist has been doing some reading in The King in Yellow and is now suffering from some rather crippling paranoia. Because of how quickly the story moves, I can’t say much more without giving spoilers, but this is probably the most fun of the first four stories. In perfect contrast to the previous work which ends somewhat positively, the finale of “In the Court of the Dragon” is downright insane.

The last of the first four stories is called “The Yellow Sign,” and it takes place in New York. This time, our main character is a painter by the last name of Scott. Mr. Scott may be the most connected character in the entire collection as he seems to appear in three separate stories and is even aware of the events in a fourth. In “The Yellow Sign ,” Scott is joined by his art model Tessie in a slow-burning tale of impending death and gloom. As the title suggests, the story largely focuses on The Yellow Sign, an oft mentioned McGuffin throughout the previous three tales. Just like Scott himself, “The Yellow Sign” is the most interconnected of the stories and brings a lot of previous hints and clues together. No wonder, as this is clearly the finale of the arc the first four stories create.

Indeed, when one is referring to The King in Yellow , one is typically speaking of the first four stories. The fifth and seventh are unrelated to the first four but are still spooky in their own right, while the sixth is no story at all. It is rather a collection of short poems which add much-appreciated lore to the first four stories and should really have been listed fifth instead of sixth. The eighth story isn’t horror per se but is certainly disturbing enough and will engender plenty of tension, if not fear.

The final two stories sadly have no relation to the previous eight and exit the realm of horror altogether, much as Chambers himself would do. Stories nine and ten are pleasant, though unremarkable, romances in Paris featuring a naive American protagonist. They are exactly what they sound like, and we are not here for that!

Still, the first four stories alone make reading the collection worth your while, and since it is entirely available within the public domain, you have nothing to lose. Once you’ve read the first four stories, you can make your own decision about going on, but I think you’ll wish to. I certainly did.

There are also several excellent audio versions available on Audible or even YouTube. My all-time favorite narrator, Ian Gordon, has an outstanding channel called Horrorbabble where he has narrated hundreds of great horror stories, including The King in Yellow and the nearly completed works of H.P. Lovecraft. If you do decide you’re interested in checking it out, his rendition is one of the best .

Alternatively, I myself have recorded a complete audio version of The King Yellow, which is available on Audible .

In the end, if you like Lovecraft, you’ll like Chambers too, at least to the extent that he writes horror. For those of us who have already read or listened to every scrap of Lovecraft available, The King in Yellow is a chilling and sinister way to get your fix.

[1] “Robert Chambers, Novelist, Is Dead,” The New York Times , December 1933, p. 36.

[2] Jonathan Nield, “A Guide to the Best Historical Novels and Tales,” in A Guide to the Best Historical Novels and Tales (New York, NY: B. Franklin, 1968), pp. 91-114.

[3] H. P. Lovecraft et al., “Selected Letters Vol II.,” in Selected Letters Vol II. (Sauk City, WI: Arkham House, 1968), p. 148.

[4] H. P. Lovecraft, Supernatural Horror in Literature. With a New Introd. by E.F. Bleiler (New York: Dover Publications, 1973).

JOIN THE CULT OF HORROR R

Step into the shadows and become part of our growing community of over 24,000 horror enthusiasts.

We don’t spam! Read our privacy policy for more info.

Check your inbox or spam folder to confirm your subscription.

Cosmic Horror Horror fiction horror literature King in Yellow Robert W Chambers Ian Gordon Horrorbabble H.P. Lovecraft

One Comment

If you enjoyed my perspective here on Horror Obsessive, then please consider listening to my Podcast on a very different subject.

I’m the host of Modernist Monastery, it’s about the connection between ancient philosophical or spiritual practices and modern scientific research. It’s also a show about how to apply that connection to your everyday life

https://modernistmonastery.transistor.fm/

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Written by Dean Delp

A content creator and editor by both passion and trade. Obsessed with the strange, interesting, intelligent and otherwise unusual. Podcaster, writer, filmmaker, narrator, and voice actor.

Creepshow Season 2 Premiere Throws It Way Back and Strikes Gold

Soho Horror Film Fest Matt Mercer Weekend: Dementia Part II, Someone’s At Your Door, and Feeding Time

Copyright @2020-2024 by Horror Obsessive

Username or Email Address

Remember Me

Forgot password?

Enter your account data and we will send you a link to reset your password.

Your password reset link appears to be invalid or expired.

Privacy policy.

To use social login you have to agree with the storage and handling of your data by this website.

Add to Collection

Public collection title

Private collection title

No Collections

Here you'll find all collections you've created before.

IMAGES

VIDEO