An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

The Relationship Between Motivation and Academic Performance Among Medical Students in Riyadh

Khalid a bin abdulrahman, abdulrahman s alshehri, khalid m alkhalifah, ahmed alasiri, mohammad s aldayel, faisal s alahmari, abdulrahman m alothman, mohammed a alfadhel.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Abdulrahman S. Alshehri [email protected]

Corresponding author.

Accepted 2023 Oct 10; Collection date 2023 Oct.

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Background: Motivation is the process whereby goal‐directed activities are initiated and sustained. Motivation is a crucial factor in academic achievement. The study aims to measure students' demographic factors and external environments' effect on their motivation and determine the impact of students' motivation and self-efficacy on their learning engagement and academic performance.

Methodology: This is a cross-sectional study that involved distributing an online digital questionnaire, which was applied in the capital of Saudi Arabia, "Riyadh." The students’ motivation was assessed using three scales that are designed to measure the students' intrinsic/extrinsic motivation, self-efficacy, and learning engagement.

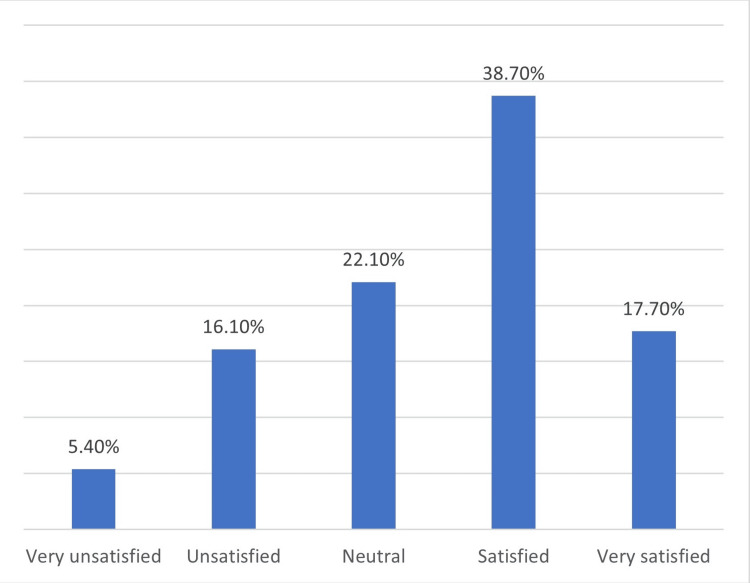

Results: In this study, we collected 429 responses from our distributed questionnaire among medical students where males represented 60.1% of the sample. Moreover, we classified the satisfaction level into five subcategories: very satisfied, satisfied, neutral, unsatisfied, and very unsatisfied. We found that most of the students (38.7%) were satisfied with their academic performance, while 17.7% were strongly satisfied. The mean enrollment motivation score in this study was 19.83 (SD 2.69), and when determining its subcategories, we found that the mean intrinsic motivation score was 10.33 (out of 12) and the mean extrinsic motivation score was 10.23 (out of 12). Moreover, the mean self-efficacy score was 9.61 and the mean learning engagement score was 8.97 (out of 12). Moreover, we found that a longer duration needed by the students to reach the college from their residence is significantly associated with lower learning engagement reported by the students (8.54 vs. 9.13 in shorter times, P=0.034). Finally, we found that students who entered medical school as their first choice had significantly higher intrinsic motivation, extrinsic motivation, self-efficacy, and learning engagement.

Conclusion: A student's preference for entering medical school will affect their motivation, self-efficacy, and learning engagement. Moreover, intrinsic and extrinsic motivations significantly correlate with self-efficacy and satisfaction with academic performance; however, they have no effect on the grade point average (GPA) of the last semester. The only factor that positively correlates with students' GPA is learning engagement.

Keywords: ability-performance motivation, family medicine, analyzing, evaluation of performance, medical school students

Introduction

"Motivation is the process whereby goal‐directed activities are initiated and sustained"[ 1 ]. However, there is no consensual definition of motivation regarding the dozens of theories built around the concept. Among these, the social cognitive approach has gained considerable importance in studying motivation because it is considered a highly integrative and holistic way of understanding the concept of motivation to learn. According to this approach, motivation to learn is determined by both the individual himself and the environment. More precisely, it results from the constant interaction between a student's perceptions of his learning environment, learning behavior, and environmental factors [ 2 ]. All human beings share the motivation to secure their basic survival needs, including communication with each other, food, water, sex, and adaptation. To achieve these needs, motivation is a fundamental requirement at the right time. The concept of motivation is a useful summary concept for how the organism's internal physiological states, current environmental conditions, and the organism's history and experiences interact to modulate goal-directed activity [ 3 ].

Motivation is a crucial factor in academic achievement [ 4 ]. Precisely, the higher the motivation of medical students, the better their quality of learning, their learning strategies, persistence, and academic performance [ 2 ]. Motivation is a concept that has attracted researchers for many decades. Medical education has recently become interested in motivation, having always believed that medical students should be motivated because of their involvement in highly specific training, leading to a particular profession. However, medical students who have an absence of motivation are discouraged and have lost interest in their studies, with a feeling of powerlessness or resignation [ 2 ].

Academic motivation is one of the concepts studied with respect to student engagement. A previous study conducted by Skinner et al. looked at student participation as a result of their initiatives [ 5 ]. In addition, without engagement, there is no effective psychological cycle in learning and development. Moreover, Dörnyei found that students, even those with a high level of self-efficacy, find it difficult to understand the whole unless they are actively involved in learning [ 6 ]. Lin discussed the relationship between academic motivation and student engagement and considered academic motivation as a form of discipline that affects a person's behavior positively or negatively [ 7 ]. In addition, academic motivation, along with student involvement, influences one's goals, past experiences, cultural background, and the opinions of teachers and peers. Self-efficacy expresses one's belief in overcoming adversity [ 8 ]. Bandura et al. defined the word as an individual achieving the desired academic results. If students believe they can complete a task, they are more likely to engage in it. After Bandura et al. introduced the definition, the relationship between self-efficacy and academic success was discovered [ 9 ]. According to the results of the study, students with high levels of participation are more self-efficient than students with low levels of participation; It has been observed that these students spend a lot of time learning [ 10 ].

The impact and the influence of motivation on students' academic achievements and how motivation plays a vital role in learning have been well researched; many well-conducted studies over the past decades have shown that students' motivation has a high positive correlation with their academic performance. Internationally, a recent cross-sectional study in China in 2020 investigated the relationships between medical students' motivation and self-efficacy, learning engagement, and academic performance. They collected data from 1930 medical students by using an electronic questionnaire and data provided by their institutions; they found that the effectiveness of intrinsic motivation (e.g., if they have a strong interest in medicine) on academic performance is larger than that of extrinsic motivation (e.g., if their family or friends strongly encourage them to choose medicine). The direct effect of self-efficacy on academic performance was not significant. In addition, in this study, gender plays an important role. They found that male students have higher intrinsic motivation but surprisingly lower academic performance in comparison to females [ 11 ]. In a subsequent cross-sectional study conducted in 2018, 4,290 medical students from 10 countries in Latin America were among the students. This study investigates if the motivation that pushed Latin American students to choose a medical career is associated with their academic performance during their medical studies [ 12 ].

Different types of motivation have been shown to positively impact study technique, academic performance, and adjustment in students in education areas other than medical education [ 13 ]. Studying motivation, especially in medical students, is very important because clinical education is not quite the same as general education in different aspects. Some of them require clinical work alongside study. A recent study in the Netherlands created motivational profiles of medical students using high or low intrinsic and controlled motivation. It assessed whether different motivational profiles are associated with various academic performance results. They found high intrinsic motivation with low controlled motivations related to great study hours, deep learning strategy, good academic performance, and low exhaustion from studying. High intrinsic high controlled motivation was also associated with a good learning profile, except that those students with this profile showed high surface strategy. Low intrinsic high controlled and low intrinsic low controlled motivation was related to the least desirable learning practice [ 14 ]. Another study conducted in Iran investigated the relationship between academic self-efficacy and academic motivation among Iran's medical science students. Two hundred sixty-four undergraduate students at Qom University of Medical Sciences were selected through a random sampling method. They completed a questionnaire consisting of three sections: demographic characteristics, academic motivation, and academic self-efficacy. They found that achievement scores at the end of each semester and all scores on self-efficacy were altogether associated with academic motivation, while there was no noteworthy relationship between some demographic factors (e.g., age, gender) and academic motivation [ 15 ]. That confidence in academic performance outside of the classroom resulted in students' success. Such performance encourages the student to have faith in themselves and their self-efficacy and be more academically motivated. As time goes on, year after year, students lose their motivation.

Our study aims to measure students' demographic factors and external environments' effect on their motivation and determine the impact of students' motivation and self-efficacy on their learning engagement and academic performance. With that being stated, we believe motivation is a critical aspect of elevating academic performance. We aim to explore the relationship between motivation and academic performance in Riyadh medical schools to promote motivation and improve academic performance and outcomes.

Materials and methods

Study design and setting

This is a cross-sectional study that involved distributing an online digital questionnaire, which was applied in the capital of Saudi Arabia, "Riyadh."

Study subjects

The study population is all current medical students in medical schools in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. The sample size was estimated via calculation using the sample size formula to assume that the number of medical students in Riyadh is 6,000, 95% confidence level, and 5% margin of error resulting in a sample size of 362. Inclusion criteria encompassed all current medical students in Riyadh, while students outside Riyadh were excluded.

Study tools

In this study, we depended on the questionnaire that was validated and used in a previous study conducted in a different setting [ 11 ]. The questionnaire consisted of two main parts: the first part included questions about the demographic factors of the students including gender, level, time needed from student’s residency to reach the university, and method of admission to medical school. The second part was divided into three parts including enrollment motivation, self-efficacy, and learning engagement. The three subscales were designed to measure the students' intrinsic/extrinsic motivation, self-efficacy, and learning engagement, respectively. In particular, the enrolment motivation scale was adapted from the academic motivation scale (AMS) [ 16 ]. The AMS scale consisted of 20 items which represent 42.2% of the total variance and discovered three factors: self-discovery, using the knowledge, and discovery. Internal consistency changed between 0.72 and 0.88 in both factors, and the total scale’s Cronbach alpha value was 0.92 [ 17 ], while the learning engagement scale was adapted from the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale (UWES) for students [ 18 ]. The UWES-9S is a nine-item self-report scale grouped into three subscales with three items each: vigor, dedication, and absorption [ 19 ]. All items were scored on a seven-point frequency rating scale ranging from 0 (never) to 6 (always).

Statistical analysis

The collected data was cleaned, entered, and analyzed using SPSS Statistics version 23 (IBM Corp. Released 2015. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 23.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.). Frequency and percent were used for the description of categorical variables, while mean, SD, maximum, and minimum were used for the description of ongoing variables. ANOVA test was used to find the correlation between the scores of both tools with the status of vision. All statements were considered significant if the p-value was less than 0.05.

Ethical consideration

The study was conducted after receiving ethical approval from Imam Mohammed Ibn Saud Islamic University, College of Medicine (19-2021). All patients had to provide consent before participating in the questionnaire.

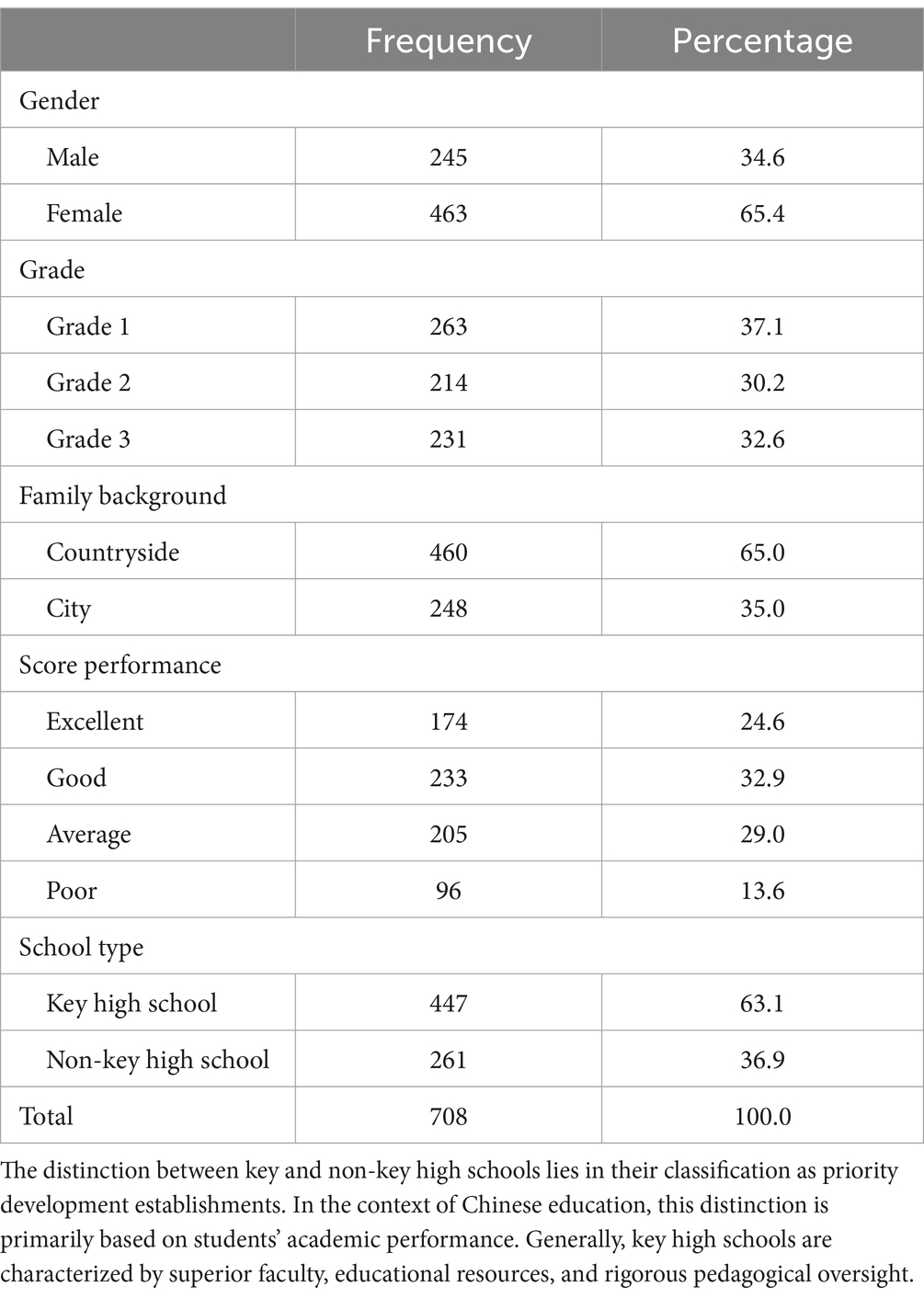

In this study, we collected 429 responses from our distributed questionnaire among medical students with an 85% response rate, where males represented 60.1% of the sample. Considering the marital status of the students, we found that almost all of the students were single. Moreover, 41.7% of students claimed that getting to their medical school from their residence required them to travel for 15 to 30 minutes each day, while 31.9% needed less than 15 minutes and 26.3% needed more than half an hour. Furthermore, 24.9% of the students were in year 1, while 23.1% were in year 3, and 22.8% were in year 2. Moreover, we found that 93.7 % of the students entered medical school as their first choice and 41.3% indicated that they had a grade point average (GPA) of 4.75-5 in the last semester. Furthermore, we found that 71.8% of the students thought that they had the complete motivation to complete their education, whereas family members were the main persons who gave them the motivation (69%), as shown in Table 1 .

Table 1. Demographic factors of the students (N=429).

GPA: grade point average

As represented in Figure 1 , we found that 38.7% of the students were satisfied with their academic performance, while 17.7% were strongly satisfied; however, 16.1% of the students were unsatisfied with their academic performance, while 5.4% were very unsatisfied.

Figure 1. Students' satisfaction with their academic performance.

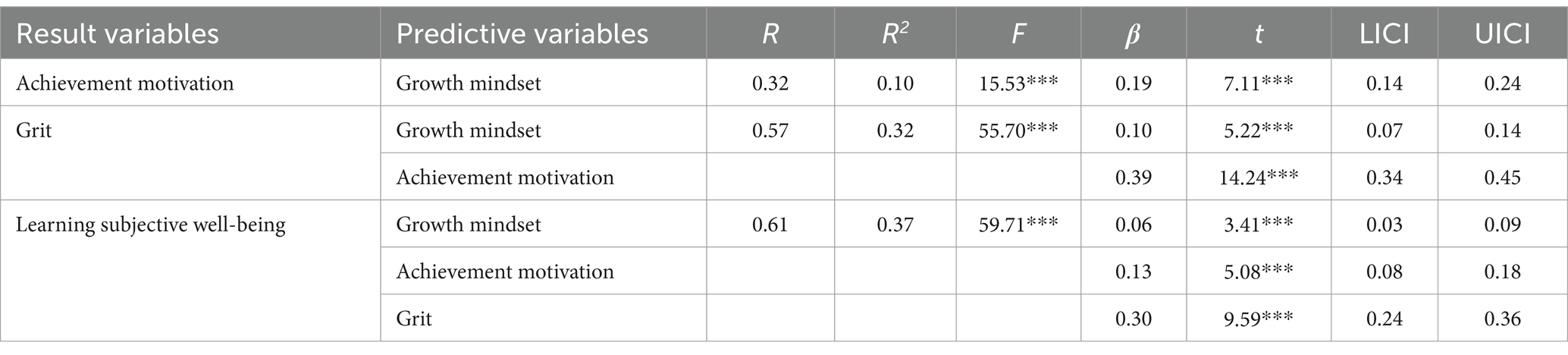

Moreover, in this study, we used three scales to assess three factors of the students including their enrollment motivations, self-efficacy, and learning involvement. Enrollment motivation scores in this study ranged from 8 to 24 with a mean score of 19.83 (SD: 2.69), and when determining its subcategories, we found that the mean intrinsic motivation score was 10.33 (out of 12), and the mean extrinsic motivation score was 10.23 (out of 12). Moreover, the self-efficacy score ranged from 2 to 12 with a mean score of 9.61, and the mean learning engagement score was 8.97 (out of 12), as shown in Table 2 .

Table 2. Mean, SD, minimum, and maximum scores of the three scales including enrollment motivation, self-efficacy, and learning engagement.

In this study, we found that entering medical school as the first choice or not significantly affects enrolment motivations, where students who entered medical school as their first choice had significantly higher intrinsic motivation, extrinsic motivation, self-efficacy, learning engagement, students’ motivation, and enrollment motivation. Moreover, we did not find any significant differences among students with different GPAs depending on their motivation, self-efficacy, or learning engagement. However, when dividing the students into two groups with GPAs lower and higher than 4.5, we found a significant difference between the two groups. Intrinsic motivation was significantly higher in students with higher GPAs than other students (10.35 vs. 10.06, P=0.04), as well as considering self-efficacy where students with GPAs higher than 4.5 reported a higher level of self-efficacy (9.79 vs. 9.34, P=0.012) and higher learning engagement in students with GPAs higher than 4.5 (9.15) than those with GPAs lower than 4.5 (8.72) (P=0.035). Extrinsic motivation was higher in students with higher GPAs but with no significant difference (P=0.175). Considering students’ enrollment motivation, we found that students with higher GPAs have a higher level of enrollment motivation and a significantly higher level of students’ motivation than those with lower GPAs (Table 3 ).

Table 3. The relationship between students’ demographic factors and their motivation, self-efficacy, and learning engagement.

* Significant at p-value less than or equal to 0.05

IM: intrinsic motivation, EM: extrinsic motivation, SE: self-efficacy, LE: learning engagement, GPA: grade point average

In Table 4 , we showed the correlation between enrollment motivation and self-efficacy, learning engagement, and GPA. We found that intrinsic and extrinsic motivation significantly correlate with self-efficacy and learning engagement; however, they had no effect on the GPA of the last semester. The only factor that was positively correlated with the GPA of students was learning engagement, where the higher the learning engagement score of the students, the higher their GPA (Table 4 ).

Table 4. The correlation between enrollment motivation and self-efficacy, learning engagement, and GPA and their satisfaction with academic performance.

IM: intrinsic motivations, EM: extrinsic motivation, SE: self-efficacy, LE: learning engagement, GPA: grade point average

In this study, we aimed to measure the impact of students' demographic factors and external environments on their motivation and determine the impact of students' motivation and self-efficacy on their learning engagement and academic performance.

The results of this study showed that neither the gender, grade of the students, nor how far their residency had an impact on their motivation. Moreover, a student's preference for entering medical school will affect their motivation, self-efficacy, and learning engagement. Moreover, intrinsic and extrinsic motivations significantly correlate with self-efficacy and satisfaction with academic performance but have no effect on the GPA of the last semester. The only factor that positively correlated with the students' GPAs was learning engagement. A study by Javadi et al. found that the mean intrinsic and extrinsic motivation score was higher in females than in males and in freshmen than higher-level students [ 20 ]. A study by Wu et al. found that male students reported significantly higher intrinsic motivation but surprisingly lower levels of academic performance than female students [ 11 ]. In another study conducted by Kusurkar et al., females had higher intrinsic motivation than males in medical education settings [ 14 ]. The only factor that affected the students’ motivation, whether intrinsic or extrinsic motivation, was their willingness to enter medical school; students who reported that entering medical school was their first choice had a significantly higher motivation than those who said it wasn't. Considering demographic factors affecting self-efficacy, we found that students' gender, grade, and willingness to enter medical school are all factors that affect their level of self-efficacy; males, older students, and those who indicated that entering medical school was their first choice all reported having higher levels of self-efficacy. Moreover, we found that there was no difference reported between genders in terms of learning engagement. However, we found that the time it takes to get to the college from residency has a significant impact on learning engagement, where students at farther residency would have lower learning engagement than those at closer residency. This result was also reported in previous studies [ 21 , 22 ]. Furthermore, we found that students who enter medical school as their first choice have a higher level of learning engagement, contrary to those who didn’t choose medical school as their first choice. These results indicated that the main factors affecting student’s motivation, self-efficacy, and learning engagement are their choice and will to enter medical school. Therefore, one of the important recommendations in this study is to let students choose their career destination [ 23 ]. In Saudi Arabia, as well as many other Arabic countries, entering medical school is a great achievement from the point of view of parents and society [ 24 ]. Therefore, this could put pressure on students to enter medical school even though this is not what they want. According to our study, this will affect their motivation, self-efficacy, and learning motivations.

Moreover, the results of this study showed that intrinsic and extrinsic motivation significantly correlate with self-efficacy, learning engagement, and satisfaction with academic performance but have no effect on the GPA of the last semester. The only factor that positively correlates with the GPA of students was learning engagement where the higher the learning engagement score of the students, the higher their GPA. This indicates that the motivations of the students have a significant impact on their learning engagement and academic performance. These results contradict those of Javadi et al. who found no significant correlation between intrinsic and extrinsic motivation and academic performance [ 20 ]. Previous studies, including that of Wu et al., found that intrinsic and extrinsic motivation was significantly and positively associated with self-efficacy and learning engagement. However, in this study, extrinsic motivation had no significant association with the students’ academic performance while intrinsic motivations had [ 11 ]. Moreover, these results were also found in other studies including that of Fan et al. [ 25 ], Walker et al. [ 26 ], Bakker [ 27 ], and Baker [ 28 ]. Moreover, previous studies confirmed a positive relationship between learning engagement and academic performance found in this study [ 29 , 30 ].

Limitations

This study has some limitations. One of these limitations is the dependence on self-reported questionnaires which could lead to some personal bias including the desire of students to appear better. Moreover, we depended on students’ self-report of their GPA of the last semester which could lead to some bias including remember bias and personal bias where students would tend to report higher scores. The study’s sample size and gender distribution might limit the generalizability of the findings. Addressing these limitations through diverse samples and longitudinal studies would enhance the study’s quality and enrich the insights drawn from its results.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we found that students’ will to enter medical school is the main factor affecting their motivation, self-efficacy, and learning engagement. Moreover, intrinsic and extrinsic motivations significantly correlate with self-efficacy, learning engagement, and satisfaction with academic performance but have no effect on the GPA of the last semester. The only factor that positively correlates with the students' GPA is learning engagement.

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Author Contributions

Concept and design: Abdulrahman S. Alshehri, Khalid A. Bin Abdulrahman, Khalid M. Alkhalifah, Ahmed Alasiri, Mohammad S. Aldayel, Faisal S. Alahmari, Abdulrahman M. Alothman, Mohammed A. Alfadhel

Drafting of the manuscript: Abdulrahman S. Alshehri, Khalid M. Alkhalifah, Ahmed Alasiri, Mohammad S. Aldayel, Faisal S. Alahmari, Abdulrahman M. Alothman, Mohammed A. Alfadhel

Critical review of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Khalid A. Bin Abdulrahman, Khalid M. Alkhalifah, Ahmed Alasiri, Mohammad S. Aldayel, Faisal S. Alahmari, Abdulrahman M. Alothman, Mohammed A. Alfadhel

Supervision: Khalid A. Bin Abdulrahman

Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: Khalid M. Alkhalifah, Ahmed Alasiri, Mohammad S. Aldayel, Faisal S. Alahmari, Abdulrahman M. Alothman, Mohammed A. Alfadhel

Human Ethics

Consent was obtained or waived by all participants in this study. Imam Mohammad Ibn Saud Islamic University Institutional Review Board (IRB) issued approval 19-2021

Animal Ethics

Animal subjects: All authors have confirmed that this study did not involve animal subjects or tissue.

- 1. Motivation to learn: an overview of contemporary theories. Cook DA, Artino AR Jr. Med Educ. 2016;50:997–1014. doi: 10.1111/medu.13074. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 2. Motivation in medical education. Pelaccia T, Viau R. Med Teach. 2017;39:136–140. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2016.1248924. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 3. The behavioral neuroscience of motivation: an overview of concepts, measures, and translational applications. Simpson EH, Balsam PD. Curr Top Behav Neurosci. 2016;27:1–12. doi: 10.1007/7854_2015_402. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 4. Motivation and academic achievement in medical students. Yousefy A, Ghassemi G, Firouznia S. J Educ Health Promot. 2012;1:4. doi: 10.4103/2277-9531.94412. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 5. A motivational perspective on engagement and disaffection: conceptualization and assessment of children's behavioral and emotional participation in academic activities in the classroom. Skinner EA, Kindermann TA, Furrer CJ. Educ Psychol Meas. 2008;69:493–525. [ Google Scholar ]

- 6. Motivation in action: towards a process-oriented conceptualisation of student motivation. Dörnyei Z. Br J Educ Psychol. 2000;70 Pt 4:519–538. doi: 10.1348/000709900158281. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 7. Lin T-J. Student engagement and motivation in the foreign language classroom. 2012. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED547714 https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED547714

- 8. The relations between student motivational beliefs and cognitive engagement in high school. Walker CO, Greene BA. J Educ Res. 2009;102:463–472. [ Google Scholar ]

- 9. Impact of self-regulatory influences on writing course attainment. Zimmerman BJ, Bandura A. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.3102/00028312031004845 Am Educ Res J. 1994;31:845–862. [ Google Scholar ]

- 10. Development during adolescence: the impact of stage-environment fit on young adolescents' experiences in schools and in families. Eccles JS, Midgley C, Wigfield A, Buchanan CM, Reuman D, Flanagan C, Mac Iver D. Am Psychol. 1993;48:90–101. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.48.2.90. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 11. Medical students' motivation and academic performance: the mediating roles of self-efficacy and learning engagement. Wu H, Li S, Zheng J, Guo J. Med Educ Online. 2020;25:1742964. doi: 10.1080/10872981.2020.1742964. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 12. Motivation towards medical career choice and academic performance in Latin American medical students: a cross-sectional study. Torres-Roman JS, Cruz-Avila Y, Suarez-Osorio K, et al. PLoS One. 2018;13:0. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0205674. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 13. Motivational profiles from a self-determination perspective: The quality of motivation matters. Vansteenkiste M, Sierens E, Soenens B, Luyckx K, Lens W. J Educ Psychol. 2009;101:671–688. [ Google Scholar ]

- 14. Motivational profiles of medical students: association with study effort, academic performance and exhaustion. Kusurkar RA, Croiset G, Galindo-Garré F, Ten Cate O. BMC Med Educ. 2013;13:87. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-13-87. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 15. Relationship between academic self-efficacy and motivation among medical science students. Taheri-Kharameh Z, Sharififard F, Asayesh H, Sepahvandi M, Hoseini MH. J Clin Diagnostic Res. 2018;7:0–10. [ Google Scholar ]

- 16. The academic motivation scale: a measure of intrinsic, extrinsic, and amotivation in education. Vallerand RJ, Pelletier LG, Blais MR, Briere NM, Senecal C, Vallieres EF. Educ Psychol Meas. 1992;52:1003–1017. [ Google Scholar ]

- 17. Student engagement, academic self-efficacy, and academic motivation as predictors of academic performance. Dogan U. Anthropol. 2015;20:553–561. [ Google Scholar ]

- 18. WB S, AB B. Utrecht work engagement scale—Italian version. Utrecht Work Engagement Scale (UWES) preliminary manual, Occupational Health Psychology Unit. Published online. 2003. https://psycnet.apa.org/doiLanding?doi=10.1037%2Ft01350-000 https://psycnet.apa.org/doiLanding?doi=10.1037%2Ft01350-000

- 19. The measurement of work engagement with a short questionnaire. Schaufeli WB, Bakker AB, Salanova M. Educ Psychol Meas. 2006;66:701–706. [ Google Scholar ]

- 20. Relationship between motivation and academic performance in students at Birjand University of Medical Sciences. Javadi A, Faryabi R. http://edcbmj.ir/article-1-974-en.html Educ Strategy Med Sci. 2016;9:142–149. [ Google Scholar ]

- 21. Staying close or going away: how distance to college impacts the educational attainment and academic performance of first-generation college students. Garza AN, Fullerton AS. Sociol Perspect. 2018;61:164–185. [ Google Scholar ]

- 22. College residence and academic performance: who benefits from living on campus? López Turley RN, Wodtke G. Urban Educ. 2010;45:506–532. [ Google Scholar ]

- 23. The influences of perceived social support and personality on trajectories of subsequent depressive symptoms in Taiwanese youth. Lien YJ, Hu JN, Chen CY. Soc Sci Med. 2016;153:148–155. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.02.015. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 24. Selection of medical students and its implication for students at King Faisal University. Kamal BA. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3410121/ J Family Community Med. 2005;12:107–111. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 25. The effects of parental involvement on students’ academic self‐efficacy, engagement and intrinsic motivation. Fan W, Williams CM. Educ Psychol. 2010;30:53–74. [ Google Scholar ]

- 26. Identification with academics, intrinsic/extrinsic motivation, and self-efficacy as predictors of cognitive engagement. Walker CO, Greene BA, Mansell RA. Learn Individ Differ. 2006;16:1–12. [ Google Scholar ]

- 27. An evidence-based model of work engagement. Bakker AB. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2011;20:265–269. [ Google Scholar ]

- 28. Intrinsic, extrinsic, and amotivational orientations: Their role in university adjustment, stress, well-being, and subsequent academic performance. Baker SR. Curr Psychol. 2007;23:189–202. [ Google Scholar ]

- 29. The relationship between self-efficacy and self-regulated learning in one-to-one computing environment: the mediated role of task values. Li S, Zheng J. Asia-Pacific Educ Res. 2018;27:455–463. [ Google Scholar ]

- 30. The relationship between student engagement and academic performance: is it a myth or reality? Lee JS. J Educ Res. 2014;107:177–185. [ Google Scholar ]

- View on publisher site

- PDF (210.9 KB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 21 October 2024

Mediating role of academic self-efficacy and academic emotions in the relationship between teacher support and academic achievement

- Bingjie Xu 1

Scientific Reports volume 14 , Article number: 24705 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

239 Accesses

Metrics details

- Human behaviour

Academic achievement reflects students’ learning outcomes over a period of time and serves as a crucial gauge of student learning levels, as well as a focal point of societal interest. To investigate the impact of teacher support on academic achievement and its mechanism of action, this study introduces two mediating variables—academic self-efficacy and academic emotions—to construct a chain mediation model, and conducts a survey among 800 university students in Nanjing. The findings reveal that teacher support directly impacts academic achievement; academic self-efficacy mediates the effect of teacher support on academic achievement; academic emotions also mediate the effect of teacher support on academic achievement; and there is a chain mediating effect of academic self-efficacy and academic emotions in the relationship between teacher support and academic achievement. This research elucidates the relationship between teacher support and academic achievement, providing a theoretical foundation and practical recommendations for enhancing the academic performance of university students.

Similar content being viewed by others

Effect of teacher social support on students’ emotions and learning engagement: a U.S.-Chinese classroom investigation

Online class-related boredom and perceived academic achievement among college students: the roles of gender and school motivation

Academic self-discipline as a mediating variable in the relationship between social media addiction and academic achievement: mixed methodology

Introduction.

Within the sphere of higher education, academic achievement is universally acknowledged as a pivotal metric of university students’ academic progression, attracting extensive scholarly and societal interest 1 . It serves not merely as a reflection of transitions in learning from elementary to advanced stages but also as a fundamental criterion for assessing the pedagogical efficacy of higher education institutions 2 . The past few years have witnessed devastating incidents involving Chinese university students, whose academic struggles have led to tragic outcomes, thereby igniting widespread societal concerns. For instance, in 2019, a student from a Beijing university, identified as Zhang, faced the inability to graduate on account of academic shortcomings and, despite an additional year’s effort, failed to meet the requisite course completions. This led Zhang to make the harrowing decision to end his life by leaping from the 18th floor of a building, following his return to the institution to retrieve his completion certificate. Similarly, in 2022, a distressing attempt was made by a 19-year-old female student who, in the wake of failing her final examinations, ingested 293 antipsychotic pills. These heartrending events not only elicit deep sorrow but also underscore the imperative for a comprehensive examination of the determinants of academic achievement.

Contemporary research into the factors influencing university students’ academic performance predominantly concentrates on two dimensions: individual student characteristics and their external milieu. Within this context, particular emphasis has been placed on the significant influence of external environmental factors, as highlighted by Xiao and Jian 3 investigation, which reveals a positive association between family economic status and academic achievement. Recent research has further corroborated this by indicating that socio-economic background and family support systems are crucial predictors of academic success in university students 4 . Nonetheless, the role of teachers, as a crucial element of this external environment, remains instrumental in shaping students’ educational journeys. While existing studies have largely focused on the impact of teacher support at the primary and secondary education levels, there remains a paucity of research examining the effect of university educators’ support on the academic outcomes of university students 5 , 6 . Additionally, much of the scholarly discourse has been oriented towards understanding academic achievement from the perspective of the students themselves, acknowledging the pronounced independence and autonomy characteristic of this demographic 7 . This autonomy is particularly influential on their academic performance, notably at the psychological level. Studies have delineated the direct impact of cognitive factors and the indirect influence of emotional factors on academic achievement, mediated through cognitive pathways 8 , 9 . Researchers such as Tong and Miao 10 have explored the correlation between university students’ self-efficacy and their academic outcomes, discovering that elevated self-efficacy levels correlate positively with improved academic performance, with optimism serving as a mediator. Furthermore, Zhao et al. 11 have investigated the linkage between students’ academic emotions and their academic performance, unveiling a positive correlation between affirmative academic emotions and academic achievement. Despite these insights, there is a notable dearth of research concurrently examining cognitive and emotional factors as mediators in academic achievement.

In the discussion on the relationship between teacher support and academic achievement, significant advancements have been made by scholars, both domestically and internationally 5 , 12 . Efforts to decipher the intricate mechanism through which teacher support influences academic achievement have led to empirical inquiries into the interactions among teacher support, academic self-efficacy, academic emotions, and academic achievement 13 , 14 . Yet, the exploration specifically targeting university students, particularly regarding the chain mediating role of academic self-efficacy and academic emotions in the context of teacher support and academic achievement, remains limited. This study, therefore, seeks to extend the body of existing research by examining the mechanisms through which teacher support impacts the academic achievement of university students, with a focus on the intricate mediating roles played by academic self-efficacy and academic emotions.

This investigation makes significant contributions on two fronts: theoretically, it augments the domestic corpus of research concerning the academic achievement of university students, a domain previously dominated by studies on familial, parental, policy, and personal influences, while often neglecting the pivotal impact of university educators on students’ academic endeavors 15 , 16 , 17 . Practically, it offers actionable insights for the enhancement of academic outcomes among university students. By delving into the effects of teacher support, alongside the mediating roles of academic self-efficacy and academic emotions, this study equips educators and administrators in higher education with the necessary understanding to tailor their pedagogical and managerial approaches effectively. This, in turn, facilitates targeted interventions and enhancements in teaching and administrative practices, aiding students in bolstering their academic self-efficacy, managing their academic emotions, and, ultimately, refining their talent development capabilities.

Literature review and research hypotheses

The relationship between teacher support and academic achievement.

The concept of “teacher support,” as initially delineated by Trickett and Moos 18 , encompasses various forms of care, assistance, and encouragement that students perceive from their educators. This construct has been explored extensively by scholars globally, leading to a consensus that teacher support constitutes a multifaceted amalgam of emotional, instructional, and appraisal support 19 , 20 . These dimensions are universally recognized as pivotal in fulfilling students’ basic needs throughout their educational journey. Despite nuanced variations in definitions across different studies, the essence of teacher support invariably centers on fostering an environment conducive to learning by addressing the emotional well-being of students, enhancing their sense of competence, and providing valuable information and feedback. “Academic achievement,” on the other hand, is characterized as the culmination of students’ learning endeavors, reflecting the breadth and depth of knowledge and skills amassed over time 21 . The Grade Point Average (GPA) stands as a universally endorsed metric for gauging academic achievement, offering a comprehensive assessment of students’ learning outcomes and the caliber of their academic performance 22 .

The phenomenon known as the Rosenthal effect posits that the quality of attention and the level of care and affection bestowed by teachers upon their students can significantly bolster the latter’s confidence and positivity. This, in turn, catalyzes a more focused and engaged approach to learning 23 . Empirical evidence supports the assertion that teacher support behaviors exert a direct impact on students’ academic achievements. Studies, such as those conducted by Ouyang et al., have demonstrated that students who perceive high levels of teacher support tend to exhibit superior academic performance compared to their peers receiving less support. Similarly, research by Chen and Guo 24 has established a positive correlation between perceived teacher support behaviors and academic achievement, underscoring the potential of teacher support as a predictive factor of students’ academic success. Moreover, studies like those of Wentzel et al. 25 have shown that adolescents receiving affirmative support from teachers and peers are more likely to achieve enhanced academic and social outcomes. Further, Reyes et al. 26 have discovered that perceived teacher support plays a crucial role in amplifying student engagement and invigorating learning enthusiasm, which in turn facilitates academic achievement. In a recent study, Hoferichter et al. 27 also explored the direct impact of teacher support on students’ academic performance in their article titled “The Relationship Between Teacher and Peer Support, Student Stress, and Academic Achievement.”

These collective insights underscore the instrumental role of teacher support in bolstering academic achievement, suggesting its potential to exert a similarly positive influence on the academic performance of university students 28 . Thus, based on the evidence presented and the theoretical underpinnings of the role of teacher support, this study posits the following hypothesis for further investigation:

Teacher support is positively associated with academic achievement, implying that higher levels of perceived support from teachers are likely to result in enhanced academic outcomes among university students.

The relationship between teacher support, academic self-efficacy, and academic achievement

The construct of “self-efficacy,” first introduced by psychologist Albert Bandura in 1977, encapsulates an individual’s belief in their capacity to execute actions necessary to achieve specific performance levels 29 . Bandura’s conceptualization of self-efficacy was subsequently expanded into the educational realm as “academic self-efficacy,” which denotes students’ beliefs in their ability to mobilize the knowledge and skills they have acquired to successfully complete academic tasks.

In the context of education, teacher support is widely recognized as a pivotal element that significantly impacts students’ academic outcomes. Beyond this, academic self-efficacy stands as a critical facet of the learning ecosystem, serving as an essential bridge linking teacher support with academic achievement 30 , 31 . The teacher expectation theory posits that educators develop varying expectations for students based on perceived student attributes, which subsequently shape their interactions with and attitudes toward these students. These teacher behaviors, in turn, influence students’ perceptions and initiate internal psychological transformations that bear on their academic success 32 . Given Bandura’s assertion that self-efficacy is inherently a subjective perception, it can thus be regarded as an internal psychological attribute that plays a crucial role in academic contexts 29 .

Social cognitive theory further elucidates the dynamic interplay between teacher-student interactions and student outcomes. Marzano 33 argues that positive relational dynamics between teachers and students bolster students’ self-efficacy beliefs, which in turn, enhance academic performance. The implication here is that the extent of support rendered by teachers is directly proportional to the likelihood of fostering positive teacher-student relationships, which enhances students’ academic self-efficacy and, consequently, their academic achievement 34 . Empirical studies by Beghetto 35 and Kang and Liew 36 corroborate this theoretical framework, demonstrating a positive correlation between perceived teacher support, elevated academic self-efficacy, and improved academic outcomes. In light of these considerations, the current investigation posits the following hypothesis for further exploration:

Academic self-efficacy functions as a mediating variable in the relationship between teacher support and academic achievement, suggesting that teacher support enhances academic self-efficacy, which in turn positively influences academic achievement.

The relationship between teacher support, academic emotions, and academic achievement

Introduced by Pekrun et al. 37 , the concept of “academic emotions” encompasses the spectrum of emotional experiences directly linked to academic successes or failures within the educational setting. This definition was later broadened by Chinese scholars Yu and Dong 38 , who posited that academic emotions extend beyond reactions to academic outcomes to encompass the diverse emotional experiences encountered during learning-related activities, such as homework completion, class participation, or examination processes.

Drawing from ecological systems theory, which postulates that environmental influences typically manifest through individual internal variables, teacher support is conceptualized as an external environmental factor, whereas academic emotions are regarded as internal psychological states. Hence, the pathway from teacher support to academic achievement is potentially mediated by academic emotions, aligning with Bronfenbrenner’s 39 theoretical framework. Furthermore, basic psychological needs theory articulates that the fulfillment of individuals’ needs for autonomy, belonging, and competence fosters a conducive adaptation to social contexts 40 . Within the educational milieu, the provision of teacher support plays a critical role in meeting students’ fundamental psychological needs, which, when satisfied, engender a conducive learning environment 41 . Teacher support can be delineated into three distinct categories—autonomy support, emotional support, and competence support—each of which, when perceived by students, can invigorate their learning interest, enhance their sense of ability, and bolster their efforts. This, in turn, cultivates positive academic emotions in the face of academic endeavors, facilitating the adoption of effective learning strategies and, ultimately, fostering academic achievement 42 .

Pekrun 43 emphasized the profound impact of significant others’ (e.g., teachers) expectations and support on students’ academic performance and, correspondingly, on their academic emotions. The perception of teacher attention and expectations fosters positive learning emotions and attitudes, thereby kindling learning motivation and improving academic outcomes. This perspective has been corroborated by subsequent studies, including those by Zhang 14 , Cao 42 and Hughes et al. 44 , which have demonstrated that academic emotions serve as a mediating factor in the relationship between perceived teacher support and academic achievement. Based on these insights, the current investigation advances the following hypothesis:

Academic emotions act as a mediating variable between teacher support and academic achievement, indicating that teacher support positively influences academic emotions, which in turn contribute to enhanced academic achievement.

The relationship between teacher support, academic self-efficacy, academic emotions, and academic achievement

Pekrun’s 43 integration of social cognitive theory and cognitive motivation theory into the control-value theory of academic emotions offers a comprehensive framework for understanding the interplay between students’ perceptions of their external environment, their academic emotions, and the ensuing impact on the learning process. This theory elucidates how task characteristics, environmental factors, and evaluative judgments collectively shape students’ academic emotions and, subsequently, their learning outcomes. Specifically, the control-value theory posits that students’ assessments of the importance of a task, coupled with their belief in their ability to accomplish it, bolster their academic self-efficacy. This elevated sense of self-efficacy fosters positive academic emotions, which in turn ignite learning motivation and enhance academic achievement 42 . Accordingly, this theoretical construct underpins the hypothesis that teacher support positively impacts academic achievement via the sequential mediation of academic self-efficacy and academic emotions.

Further, Brophy and Good 32 delineated the mechanism of the teacher expectation effect as a sequence that commences with student characteristics, which shape teacher expectations, subsequently influencing teacher behavior. This behavior, in turn, informs student perceptions, which impact their emotions and, ultimately, their academic achievement. This model suggests that teachers process and interpret information about students, forming expectations that are conveyed through their behavior. Students perceive these expectations, which influences their self-perception and emotional response, aligning their efforts with the direction of the anticipated outcomes, thereby affecting their academic achievement 45 . Bandura’s 29 elaboration on the notion of “expectations” introduces the concept of efficacy expectations, emphasizing the individual’s belief in their capacity to execute behaviors necessary to produce desired outcomes. Thus, self-expectations serve as a form of self-efficacy expectation, implying that heightened self-efficacy expectations for future performance motivate individuals to improve their capabilities, thereby enhancing their academic self-efficacy.

This theoretical exploration provides a solid foundation for positing that teacher support can bolster academic self-efficacy, which, in turn, influences academic emotions and academic achievement. Therefore, this study introduces the following hypothesis for examination:

Teacher support influences academic achievement through the chain mediating effect of academic self-efficacy and academic emotions.

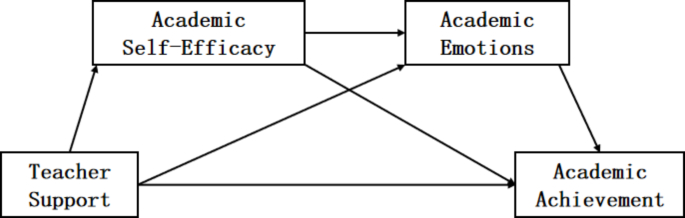

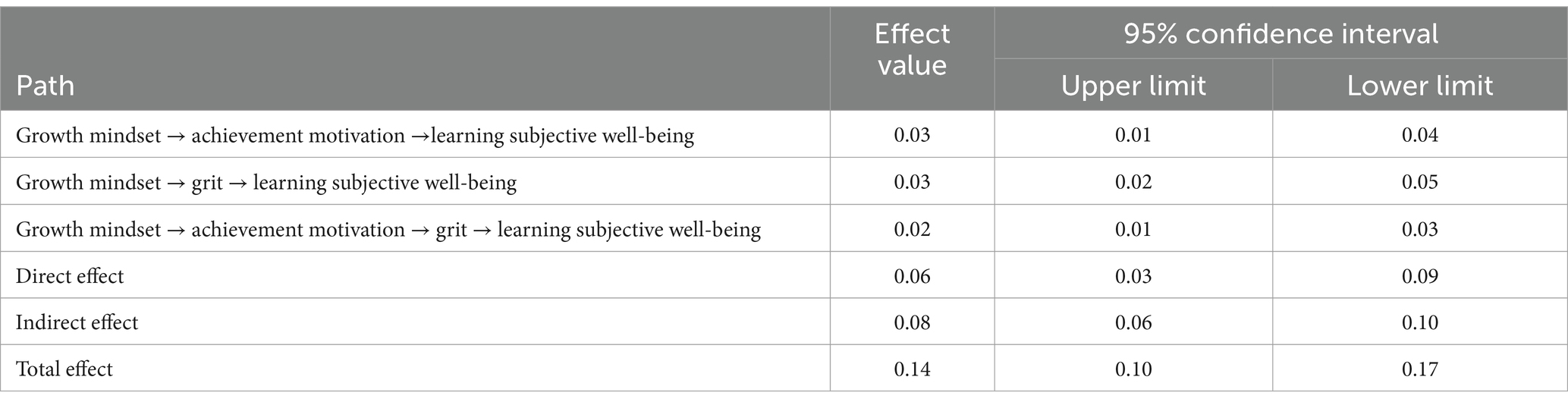

In alignment with these theoretical insights, the present study proposes a chain mediation model (refer to Fig. 1 ) designed to scrutinize the relationships among teacher support, academic self-efficacy, academic emotions, and academic achievement. This model aims to furnish empirical evidence and theoretical rationales for the proposition that enhancing teacher support can significantly elevate academic achievement through the synergistic interplay of academic self-efficacy and academic emotions.

Chain mediation model.

Research subjects and methods

Research participants.

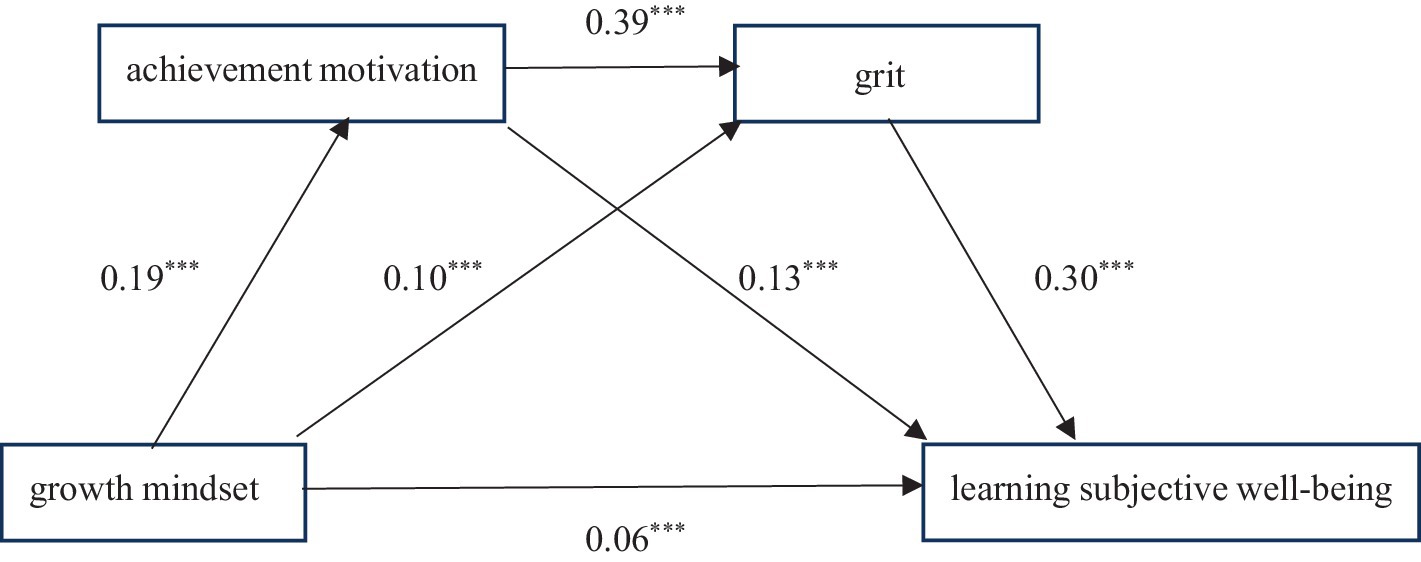

This research adopted a hybrid sampling strategy, leveraging both random and cluster sampling techniques, to recruit participants from a university located in Nanjing, Jiangsu Province. In the course of this study, a total of 800 questionnaires were disseminated among the student body, from which 781 responses were collected. Following a meticulous screening process to exclude 60 questionnaires due to incomplete basic information or answers, a final tally of 721 questionnaires was deemed valid, resulting in a validity rate of 90.125%. The gender distribution within the valid sample comprised 206 male participants, accounting for 28.571% of the sample, and 515 female participants, representing 71.429%. The participants were also categorized by their academic year, with 172 (23.856%) being first-year students, 130 (18.031%) second-year students, 194 (26.907%) third-year students, and 225 (31.207%) fourth-year students. The demographic breakdown of the sample population, which is instrumental in providing a comprehensive overview of the participant base, is systematically outlined in Table 1 . This demographic composition underscores the diversity within the study’s sample and sets the stage for a nuanced analysis of the relationships between teacher support, academic self-efficacy, academic emotions, and academic achievement within this cohort.

Research tools

- Teacher support

In this study, the multifaceted construct of teacher support was quantitatively assessed through the “Teacher Support Questionnaire” as developed by Chi Xianglan. This instrument encompasses 13 items distributed across three pivotal dimensions: autonomy support, emotional support, and competence support, employing a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (“strongly disagree”) to 5 (“strongly agree”) for responses. Higher scores on this scale denote a stronger perception of teacher support, underscoring the respondents’ positive recognition of the support provided by their educators 46 . The reliability of this scale was confirmed with a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.903. Additionally, the structural validity of the questionnaire was validated through confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), yielding favorable model fit indices: RMSEA = 0.042, X 2 /df = 2.289, TLI = 0.980, GFI = 0.987, CFI = 0.993, which collectively indicate the scale’s robustness in measuring teacher support.

- Academic self-efficacy

The “Academic Self-Efficacy Scale,” adapted by Liang Yusong from Binturish’s original instrument and tailored for Chinese students, was utilized to evaluate academic self-efficacy. This scale comprises 22 items focusing on self-efficacy in learning ability and behavior, also adopting a five-point Likert scale for responses. Scores closer to 5 reflect stronger academic self-efficacy 47 . The scale demonstrated good reliability, with a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.882, and structural validity, evidenced by CFA results showing a good model fit: RMSEA = 0.051, X 2 /df = 2.836, TLI = 0.964, GFI = 0.943, CFI = 0.974.

- Academic emotions

For measuring academic emotions, this study employed the “University Students’ Academic Emotions Scale” by Xu Xiancai, specifically focusing on the segment pertaining to positive academic emotions. This section, with 22 items, is divided into two dimensions: positive activity-oriented emotions and positive outcome-oriented emotions 48 . Responses were recorded on a five-point Likert scale, where higher scores are indicative of more intense academic emotions. The scale’s reliability was exceptionally high, as evidenced by a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.965, and its structural validity was supported by CFA results indicating a satisfactory model fit: RMSEA = 0.060, X 2 /df = 3.631, TLI = 0.966, GFI = 0.976, CFI = 0.992.

- Academic achievement

To assess academic achievement, the study leveraged the Grade Point Average (GPA) as a comprehensive metric. This quantitative measure integrates both the credit and grade points to evaluate the breadth and quality of students’ academic endeavors. GPAs were categorized into five distinct intervals for detailed analysis, with varying ranges from “fail” to “excellent,” thus facilitating a nuanced exploration of academic achievement levels among university students.

Research methods

Data analysis in this study was performed using SPSS 27.0 and AMOS 23.0, encompassing assessments of reliability and validity, common method bias, correlation, regression, and evaluation of structural equation models. Analysis of the mediation model employed the Bootstrap technique, involving 2000 resamples. Determination of mediation effects’ significance relied on the inclusion or exclusion of zero within the 95% confidence interval of the Bootstrap results.

Results and analysis

Common method bias test.

To ensure the integrity and validity of the findings, the study took into consideration the potential for common method bias (CMB), which is a concern in research utilizing self-report questionnaires. This type of bias could compromise the validity of the results by artificially inflating the associations between variables due to the shared method of data collection. To preemptively address this issue, several measures were implemented during the data collection phase, including ensuring respondent anonymity and incorporating reverse-scored items to reduce response patterns. Furthermore, a post-hoc diagnostic test, specifically Harman’s single-factor test, was conducted to evaluate the extent of CMB. This exploratory factor analysis (EFA) of all survey items, without factor rotation, identified ten distinct factors with eigenvalues exceeding 1, indicating a multifactorial structure. The most significant factor accounted for 44.072% of the total variance, falling short of the 50% threshold suggested by Podsakoff and Organ as indicative of significant common method bias. This outcome suggests that the data are not substantially affected by CMB, thereby bolstering confidence in the validity of the study’s conclusions 49 .

This meticulous approach to addressing and assessing common method bias underscores the study’s commitment to methodological rigor, ensuring that the conclusions drawn from the analysis are both reliable and reflective of genuine associations among the variables under investigation.

Descriptive statistics and correlation analysis

Descriptive statistics and correlation analyses were executed using SPSS 27.0. Findings, including means, standard deviations, and Pearson correlation coefficients, are delineated in Table 2 . Table 2 presents the descriptive statistics and correlation analysis of the variables under study. The data reveal that teacher support is highly correlated with academic self-efficacy (r = 0.884, p < 0.01), academic emotions (r = 0.888, p < 0.01), and academic achievement (r = 0.876, p < 0.01), suggesting that students who perceive higher levels of teacher support tend to exhibit stronger confidence in their academic abilities, experience more positive emotions, and achieve better academic outcomes. Additionally, academic self-efficacy is strongly correlated with academic emotions (r = 0.893, p < 0.01) and academic achievement (r = 0.842, p < 0.01), indicating that students with greater self-efficacy are more likely to experience positive academic emotions and higher achievement. Similarly, academic emotions are positively correlated with academic achievement (r = 0.837, p < 0.01), underscoring the importance of positive emotional experiences in fostering academic success. Overall, these findings highlight the pivotal role of teacher support in influencing both cognitive and emotional aspects of students’ academic performance, suggesting potential pathways for intervention.

Chain mediation effect testing

For the evaluation of mediating effects, after adjusting for demographic factors including gender, grade, only child status, place of origin, and parents’ educational levels, a structural equation model (SEM) was developed. This SEM designated teacher support as the predictor, academic achievement as the dependent variable, and academic self-efficacy and academic emotions as the mediators.

Initially, a direct effects model linking teacher support to academic achievement was formulated. Fit indices for this model included: X 2 /df = 3.370, RMSEA = 0.057, CFI = 0.989, TLI = 0.964, GFI = 0.982, signifying a good fit of the data to the model, thereby corroborating research hypothesis H1.

Subsequently, a chain mediation model featuring academic self-efficacy and academic emotions as mediators was developed. Fit indices for this model were: X 2 /df = 1.748, RMSEA = 0.032, CFI = 0.999, TLI = 0.997, GFI = 0.996, RMR = 0.002, indicating a good fit of the data to the model. Models for indirect effects 1, 2, and 3 were formulated, and the significance of mediation effects was assessed using bias-corrected percentile Bootstrap (as detailed in Table 3 ). The sequences “Teacher Support → Academic Self-Efficacy → Academic Achievement,” “Teacher Support → Academic Emotions → Academic Achievement,” and “Teacher Support → Academic Self-Efficacy → Academic Emotions → Academic Achievement” demonstrated significant indirect effects (as illustrated in Fig. 2 ). The standardized effect size for indirect effect 1 stood at 0.185, CI [0.109, 0.261]; for indirect effect 2 at 0.069, CI [0.030, 0.115]; and for indirect effect 3 at 0.068, CI [0.029, 0.113]. None of the confidence intervals for these paths included 0, signifying significant indirect effects, thus corroborating research hypotheses H2, H3, and H4. These findings underscore that both academic self-efficacy and academic emotions act as critical mediators in the nexus between teacher support and academic achievement, revealing a chain mediation effect. Such insights accentuate the significance of bolstering teacher support to enhance students’ academic self-efficacy and emotions, thereby fostering improved academic performance.

Chain mediation path diagram.

Conclusion and discussion

Drawing on extant literature, this research devised a model wherein teacher support is posited as the predictor variable, with academic self-efficacy and academic emotions acting as mediators, and academic achievement constituting the outcome variable, thereby establishing a chain mediation effect. Key findings reveal: teacher support has a direct impact on academic achievement; academic self-efficacy functions as a mediator in the relationship between teacher support and academic achievement; similarly, academic emotions serve as mediators in this dynamic; moreover, the combined influence of academic self-efficacy and academic emotions illustrates a sequential mediation effect linking teacher support and academic achievement. These insights lead to the ensuing discussion.

Direct impact of teacher support on academic achievement

This study investigates the relationship between teacher support and academic achievement, as well as the underlying mechanisms of this relationship. The findings reveal a significant positive correlation between teacher support and academic achievement. Furthermore, the direct effect of teacher support on academic achievement is substantial, confirming the validity of Hypothesis H1. This finding is consistent with the conclusions of Ouyang 20 and Hoferichter et al. 27 , both of which found that teacher support positively correlates with enhanced academic performance. In the context of contemporary shifts in educational paradigms and pedagogical innovations, the realm of university education is undergoing remarkable changes. Amidst this transformation, the role of teachers has evolved beyond the traditional scope of knowledge transmission, positioning them as critical facilitators and proponents of students’ academic journey. This evolution is especially crucial in the university setting, where effective teacher support is vital for guiding students through the complexities of higher education, fostering the development of academic skills, and enhancing professional competencies. This nuanced role of teachers underscores the need for adaptive teaching strategies that respond to diverse student needs, emphasizing the importance of personalized support to foster an environment conducive to academic excellence and professional development.

Mediating role of academic self-efficacy

The standardized effect size for the indirect effect along Path 1, “Teacher Support → Academic Self-Efficacy → Academic Achievement,” indicates that the indirect influence of teacher support on academic achievement through academic self-efficacy is significant. This finding suggests that academic self-efficacy plays a critical mediating role in the relationship between teacher support and academic achievement, thereby confirming the validity of Hypothesis H2. This finding is consistent with the conclusions of Beghetto 35 and Hughes et al. 44 , both of which found that the role of self-efficacy in mediating teacher support and academic achievement among student populations. These findings are instrumental in broadening the current dialogue within educational research, emphasizing the essential role of academic self-efficacy as a mediator between teacher support and student academic performance. This relationship highlights the profound influence teachers have in bolstering students’ confidence in their academic capabilities, thus creating an environment conducive to learning. Through sustained encouragement and constructive feedback, educators play a key role in nurturing students’ intrinsic motivation, encouraging them to navigate and surmount academic challenges, and to employ more efficient learning strategies. This dynamic interaction not only boosts students’ learning efficiency but also significantly improves their academic results, illustrating a complex, reciprocal relationship between educator encouragement and student success. Furthermore, this revelation prompts a reevaluation of educational practices, advocating for the integration of emotional and motivational support with conventional academic teaching to foster a more holistic educational experience. It suggests that enhancing teacher-student interactions to support self-efficacy can profoundly impact students’ academic trajectories, advocating for educational frameworks that emphasize the development of both cognitive skills and emotional resilience, thus facilitating a more rounded approach to student development and academic excellence.

Mediating role of academic emotions

The standardized effect size for the indirect effect along Path 2, “Teacher Support → Academic Emotions → Academic Achievement,” demonstrates that the indirect effect of teacher support on academic achievement through academic emotions is significant. This indicates that academic emotions mediate the relationship between teacher support and academic achievement, thereby confirming the validity of Hypothesis H3. This finding is consistent with the conclusions of Cao 42 and Hughes et al. 44 , both of which found that academic emotions serve as a mediator between teacher support and academic achievement. In the educational process, the role of teachers extends beyond mere instruction to include providing positive reinforcement and encouragement, which are pivotal in boosting students’ self-esteem and sparking a genuine interest in academic pursuits. This nurturing approach effectively fosters a spectrum of positive emotional experiences, such as heightened interest and joy, while concurrently mitigating feelings of anxiety and frustration that can impede learning progress. As a result, such supportive teacher-student interactions significantly enhance students’ motivation to engage deeply with their studies, setting the stage for notable improvements in academic outcomes.

This finding highlights the significant impact of teacher support on the emotional climate, influencing both learning efficacy and academic outcomes. Educators foster an environment that supports students’ emotional and cognitive growth, contributing to a holistic educational experience. Emphasizing the integration of emotional intelligence and empathy within teaching methods ensures that academic instruction is enhanced with emotional support. This approach not only maximizes academic potential but also bolsters emotional resilience, equipping students for academic and personal challenges. It advocates for an integrated educational model that positions emotional well-being as essential to academic success, underscoring the critical interplay between academic emotions and achievement.

Chain mediating role of academic self-efficacy and academic emotions

The standardized effect size for the indirect effect along Path 3, “Teacher Support → Academic Self-Efficacy → Academic Emotions → Academic Achievement,” reveals that the indirect effect of teacher support on academic achievement, through the combined influence of academic self-efficacy and academic emotions, is significant. This indicates that academic self-efficacy and academic emotions serve as sequential mediators in the relationship between teacher support and academic achievement, thereby confirming the validity of Hypothesis H4. It highlights the comprehensive role of teacher support, which transcends traditional academic instruction and material provision to encompass emotional nurturing and personal interaction. Understanding this complex relationship is crucial for developing targeted teaching strategies that not only enhance the educational experience but also significantly improve students’ academic outcomes. This analysis points to the essential integration of cognitive and emotional support in pedagogical practices, emphasizing the need for educational approaches that foster both intellectual growth and emotional well-being. Such strategies should aim to create a supportive learning environment that encourages students to develop confidence in their abilities, manage academic stresses positively, and engage more deeply with their studies. By doing so, educators can effectively stimulate students’ intrinsic motivation, facilitate a deeper connection to their learning journey, and ultimately, contribute to a more holistic development of their academic skills and emotional resilience. This expanded insight into the mediation effects of teacher support on academic achievement through self-efficacy and emotions advocates for a more nuanced understanding of educational dynamics, urging a shift towards more empathetic and supportive teaching methodologies that recognize and address the intertwined nature of students’ cognitive and emotional development.

Recommendations and strategies

Enhancing teacher support to foster mentor–mentee relationships.

The significant impact of teacher support on academic achievement underscores its pivotal role in enhancing teaching quality, fostering student development, and improving the educational environment. Teachers occupy a central role in influencing students’ academic journeys and are a crucial component of the broader social support system within universities. Therefore, it’s essential for educators to transcend traditional roles of content delivery to exemplify professional excellence, demonstrate genuine concern for student welfare, and nurture positive relationships with students. Educational institutions must prioritize comprehensive teacher training and ongoing professional development, focusing on methodologies that enable the provision of autonomy, emotional support, and skills development. Furthermore, fostering a climate of positive interactions between teachers and students strengthens the students’ support network, encouraging active participation and deeper engagement with the learning material. Ensuring teacher approachability is vital, making it easier for students to seek guidance on both academic and personal challenges. Enhancing teacher support mechanisms not only boosts academic performance but also plays a critical role in the holistic development of students, preparing them for future challenges. This marked influence of teacher support on students’ academic success highlights the indispensable role teachers play in the educational ecosystem and offers strategic insights for refining pedagogical approaches to support student achievement and well-being.

Boosting academic self-efficacy to build confident and resilient learning beliefs

Enhancing students’ academic self-efficacy significantly contributes to their resilience and optimism in the face of learning challenges, thereby facilitating superior academic performance. Strategies aimed at strengthening academic self-efficacy involve not only boosting students’ confidence through consistent positive reinforcement and support but also setting realistic and achievable learning goals that foster progress and motivation. Moreover, equipping students with effective study techniques and coping strategies is crucial for navigating academic pressures, while personalized teaching methods are essential for meeting the diverse needs of the student body. These targeted approaches allow educators to not only improve academic outcomes but also to cultivate students’ growth towards becoming confident, autonomous, and proactive learners, capable of managing their educational paths.

Additionally, incorporating feedback mechanisms that recognize and celebrate students’ incremental achievements can further reinforce self-efficacy, creating a positive loop of encouragement and success. Encouraging self-reflection and self-assessment among students can also deepen their understanding of personal strengths and areas for improvement, promoting a growth mindset. By integrating these practices, educators lay the foundation for students to develop not just academically but also emotionally and socially, preparing them for the complexities of life beyond the classroom. Ultimately, these comprehensive efforts underscore the transformative potential of enhanced academic self-efficacy in shaping students into well-rounded, lifelong learners who are equipped to tackle future challenges with confidence and adaptability, thereby enriching both their personal and professional lives.

Stimulating academic emotions to guide a positive learning attitude

Fostering positive academic emotions plays a crucial role in enhancing students’ academic achievements, whereas negative emotions can undermine their confidence and hinder their skill development. It is imperative for educators to emphasize emotional literacy as a core component of the educational process, creating a supportive and nurturing learning environment that resonates with students’ personal interests and incorporates experiential learning opportunities. By integrating these elements into the curriculum and embodying positive role models, teachers can significantly inspire and engage students. Such an environment not only stimulates students’ passion for learning but also guides them towards adopting a productive and growth-oriented mindset, which is essential for improving academic performance and encouraging comprehensive personal development.

Moreover, implementing practices that foster emotional resilience and stress management can equip students with the tools necessary to navigate academic pressures effectively. Encouraging open communication and providing a safe space for students to express their emotions and challenges can further enhance emotional well-being. Additionally, promoting collaboration and peer support within the classroom can create a sense of community and belonging, further elevating students’ positive emotional experiences. Through these multifaceted approaches, educators contribute to building a holistic educational framework that supports not just cognitive development but also emotional and social growth. This comprehensive focus on nurturing positive academic emotions and resilience not only bolsters students’ academic success but also prepares them for lifelong learning and adaptation, ensuring they emerge as well-rounded individuals ready to face the complexities of the world with confidence and a positive outlook.

Cultivating teachers’ personal care to jointly promote academic progress

To optimize university students’ academic performance, it’s essential to adopt a holistic approach that encompasses the external environment alongside cognitive and emotional considerations, acknowledging the dynamic interplay between these elements. Educators, serving as key agents of influence in students’ academic trajectories, are responsible for providing not only emotional and educational support but also a diverse array of learning materials and innovative teaching strategies. This responsibility extends to the integration of cognitive and emotional learning strategies, blending techniques for cognitive development (such as enhancing memory skills and improving time management) with methods for emotional well-being (including stress reduction and emotional regulation). Such a comprehensive approach is poised to significantly elevate students’ intellectual growth and emotional resilience.