Center for Teaching

Case studies.

Print Version

Case studies are stories that are used as a teaching tool to show the application of a theory or concept to real situations. Dependent on the goal they are meant to fulfill, cases can be fact-driven and deductive where there is a correct answer, or they can be context driven where multiple solutions are possible. Various disciplines have employed case studies, including humanities, social sciences, sciences, engineering, law, business, and medicine. Good cases generally have the following features: they tell a good story, are recent, include dialogue, create empathy with the main characters, are relevant to the reader, serve a teaching function, require a dilemma to be solved, and have generality.

Instructors can create their own cases or can find cases that already exist. The following are some things to keep in mind when creating a case:

- What do you want students to learn from the discussion of the case?

- What do they already know that applies to the case?

- What are the issues that may be raised in discussion?

- How will the case and discussion be introduced?

- What preparation is expected of students? (Do they need to read the case ahead of time? Do research? Write anything?)

- What directions do you need to provide students regarding what they are supposed to do and accomplish?

- Do you need to divide students into groups or will they discuss as the whole class?

- Are you going to use role-playing or facilitators or record keepers? If so, how?

- What are the opening questions?

- How much time is needed for students to discuss the case?

- What concepts are to be applied/extracted during the discussion?

- How will you evaluate students?

To find other cases that already exist, try the following websites:

- The National Center for Case Study Teaching in Science , University of Buffalo. SUNY-Buffalo maintains this set of links to other case studies on the web in disciplines ranging from engineering and ethics to sociology and business

- A Journal of Teaching Cases in Public Administration and Public Policy , University of Washington

For more information:

- World Association for Case Method Research and Application

Book Review : Teaching and the Case Method , 3rd ed., vols. 1 and 2, by Louis Barnes, C. Roland (Chris) Christensen, and Abby Hansen. Harvard Business School Press, 1994; 333 pp. (vol 1), 412 pp. (vol 2).

Teaching Guides

- Online Course Development Resources

- Principles & Frameworks

- Pedagogies & Strategies

- Reflecting & Assessing

- Challenges & Opportunities

- Populations & Contexts

Quick Links

- Services for Departments and Schools

- Examples of Online Instructional Modules

- Our Mission

Making Learning Relevant With Case Studies

The open-ended problems presented in case studies give students work that feels connected to their lives.

To prepare students for jobs that haven’t been created yet, we need to teach them how to be great problem solvers so that they’ll be ready for anything. One way to do this is by teaching content and skills using real-world case studies, a learning model that’s focused on reflection during the problem-solving process. It’s similar to project-based learning, but PBL is more focused on students creating a product.

Case studies have been used for years by businesses, law and medical schools, physicians on rounds, and artists critiquing work. Like other forms of problem-based learning, case studies can be accessible for every age group, both in one subject and in interdisciplinary work.

You can get started with case studies by tackling relatable questions like these with your students:

- How can we limit food waste in the cafeteria?

- How can we get our school to recycle and compost waste? (Or, if you want to be more complex, how can our school reduce its carbon footprint?)

- How can we improve school attendance?

- How can we reduce the number of people who get sick at school during cold and flu season?

Addressing questions like these leads students to identify topics they need to learn more about. In researching the first question, for example, students may see that they need to research food chains and nutrition. Students often ask, reasonably, why they need to learn something, or when they’ll use their knowledge in the future. Learning is most successful for students when the content and skills they’re studying are relevant, and case studies offer one way to create that sense of relevance.

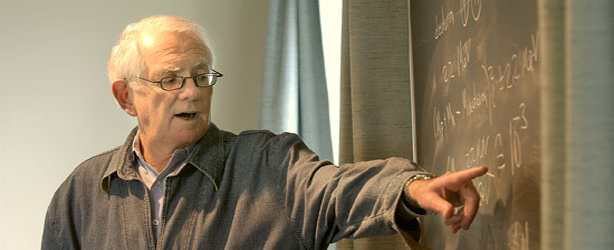

Teaching With Case Studies

Ultimately, a case study is simply an interesting problem with many correct answers. What does case study work look like in classrooms? Teachers generally start by having students read the case or watch a video that summarizes the case. Students then work in small groups or individually to solve the case study. Teachers set milestones defining what students should accomplish to help them manage their time.

During the case study learning process, student assessment of learning should be focused on reflection. Arthur L. Costa and Bena Kallick’s Learning and Leading With Habits of Mind gives several examples of what this reflection can look like in a classroom:

Journaling: At the end of each work period, have students write an entry summarizing what they worked on, what worked well, what didn’t, and why. Sentence starters and clear rubrics or guidelines will help students be successful. At the end of a case study project, as Costa and Kallick write, it’s helpful to have students “select significant learnings, envision how they could apply these learnings to future situations, and commit to an action plan to consciously modify their behaviors.”

Interviews: While working on a case study, students can interview each other about their progress and learning. Teachers can interview students individually or in small groups to assess their learning process and their progress.

Student discussion: Discussions can be unstructured—students can talk about what they worked on that day in a think-pair-share or as a full class—or structured, using Socratic seminars or fishbowl discussions. If your class is tackling a case study in small groups, create a second set of small groups with a representative from each of the case study groups so that the groups can share their learning.

4 Tips for Setting Up a Case Study

1. Identify a problem to investigate: This should be something accessible and relevant to students’ lives. The problem should also be challenging and complex enough to yield multiple solutions with many layers.

2. Give context: Think of this step as a movie preview or book summary. Hook the learners to help them understand just enough about the problem to want to learn more.

3. Have a clear rubric: Giving structure to your definition of quality group work and products will lead to stronger end products. You may be able to have your learners help build these definitions.

4. Provide structures for presenting solutions: The amount of scaffolding you build in depends on your students’ skill level and development. A case study product can be something like several pieces of evidence of students collaborating to solve the case study, and ultimately presenting their solution with a detailed slide deck or an essay—you can scaffold this by providing specified headings for the sections of the essay.

Problem-Based Teaching Resources

There are many high-quality, peer-reviewed resources that are open source and easily accessible online.

- The National Center for Case Study Teaching in Science at the University at Buffalo built an online collection of more than 800 cases that cover topics ranging from biochemistry to economics. There are resources for middle and high school students.

- Models of Excellence , a project maintained by EL Education and the Harvard Graduate School of Education, has examples of great problem- and project-based tasks—and corresponding exemplary student work—for grades pre-K to 12.

- The Interdisciplinary Journal of Problem-Based Learning at Purdue University is an open-source journal that publishes examples of problem-based learning in K–12 and post-secondary classrooms.

- The Tech Edvocate has a list of websites and tools related to problem-based learning.

In their book Problems as Possibilities , Linda Torp and Sara Sage write that at the elementary school level, students particularly appreciate how they feel that they are taken seriously when solving case studies. At the middle school level, “researchers stress the importance of relating middle school curriculum to issues of student concern and interest.” And high schoolers, they write, find the case study method “beneficial in preparing them for their future.”

- Subject List

- Take a Tour

- For Authors

- Subscriber Services

- Publications

- African American Studies

- African Studies

- American Literature

- Anthropology

- Architecture Planning and Preservation

- Art History

- Atlantic History

- Biblical Studies

- British and Irish Literature

- Childhood Studies

- Chinese Studies

- Cinema and Media Studies

- Communication

- Criminology

- Environmental Science

- Evolutionary Biology

- International Law

- International Relations

- Islamic Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Latino Studies

- Linguistics

- Literary and Critical Theory

- Medieval Studies

- Military History

- Political Science

- Public Health

- Renaissance and Reformation

- Social Work

- Urban Studies

- Victorian Literature

- Browse All Subjects

How to Subscribe

- Free Trials

In This Article Expand or collapse the "in this article" section Case Study in Education Research

Introduction, general overview and foundational texts of the late 20th century.

- Conceptualisations and Definitions of Case Study

- Case Study and Theoretical Grounding

- Choosing Cases

- Methodology, Method, Genre, or Approach

- Case Study: Quality and Generalizability

- Multiple Case Studies

- Exemplary Case Studies and Example Case Studies

- Criticism, Defense, and Debate around Case Study

Related Articles Expand or collapse the "related articles" section about

About related articles close popup.

Lorem Ipsum Sit Dolor Amet

Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia Curae; Aliquam ligula odio, euismod ut aliquam et, vestibulum nec risus. Nulla viverra, arcu et iaculis consequat, justo diam ornare tellus, semper ultrices tellus nunc eu tellus.

- Data Collection in Educational Research

- Educational Research Approaches: A Comparison

- Mixed Methods Research

- Program Evaluation

Other Subject Areas

Forthcoming articles expand or collapse the "forthcoming articles" section.

- Cyber Safety in Schools

- Girls' Education in the Developing World

- History of Education in Europe

- Find more forthcoming articles...

- Export Citations

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Case Study in Education Research by Lorna Hamilton LAST REVIEWED: 27 June 2018 LAST MODIFIED: 27 June 2018 DOI: 10.1093/obo/9780199756810-0201

It is important to distinguish between case study as a teaching methodology and case study as an approach, genre, or method in educational research. The use of case study as teaching method highlights the ways in which the essential qualities of the case—richness of real-world data and lived experiences—can help learners gain insights into a different world and can bring learning to life. The use of case study in this way has been around for about a hundred years or more. Case study use in educational research, meanwhile, emerged particularly strongly in the 1970s and 1980s in the United Kingdom and the United States as a means of harnessing the richness and depth of understanding of individuals, groups, and institutions; their beliefs and perceptions; their interactions; and their challenges and issues. Writers, such as Lawrence Stenhouse, advocated the use of case study as a form that teacher-researchers could use as they focused on the richness and intensity of their own practices. In addition, academic writers and postgraduate students embraced case study as a means of providing structure and depth to educational projects. However, as educational research has developed, so has debate on the quality and usefulness of case study as well as the problems surrounding the lack of generalizability when dealing with single or even multiple cases. The question of how to define and support case study work has formed the basis for innumerable books and discursive articles, starting with Robert Yin’s original book on case study ( Yin 1984 , cited under General Overview and Foundational Texts of the Late 20th Century ) to the myriad authors who attempt to bring something new to the realm of case study in educational research in the 21st century.

This section briefly considers the ways in which case study research has developed over the last forty to fifty years in educational research usage and reflects on whether the field has finally come of age, respected by creators and consumers of research. Case study has its roots in anthropological studies in which a strong ethnographic approach to the study of peoples and culture encouraged researchers to identify and investigate key individuals and groups by trying to understand the lived world of such people from their points of view. Although ethnography has emphasized the role of researcher as immersive and engaged with the lived world of participants via participant observation, evolving approaches to case study in education has been about the richness and depth of understanding that can be gained through involvement in the case by drawing on diverse perspectives and diverse forms of data collection. Embracing case study as a means of entering these lived worlds in educational research projects, was encouraged in the 1970s and 1980s by researchers, such as Lawrence Stenhouse, who provided a helpful impetus for case study work in education ( Stenhouse 1980 ). Stenhouse wrestled with the use of case study as ethnography because ethnographers traditionally had been unfamiliar with the peoples they were investigating, whereas educational researchers often worked in situations that were inherently familiar. Stenhouse also emphasized the need for evidence of rigorous processes and decisions in order to encourage robust practice and accountability to the wider field by allowing others to judge the quality of work through transparency of processes. Yin 1984 , the first book focused wholly on case study in research, gave a brief and basic outline of case study and associated practices. Various authors followed this approach, striving to engage more deeply in the significance of case study in the social sciences. Key among these are Merriam 1988 and Stake 1995 , along with Yin 1984 , who established powerful groundings for case study work. Additionally, evidence of the increasing popularity of case study can be found in a broad range of generic research methods texts, but these often do not have much scope for the extensive discussion of case study found in case study–specific books. Yin’s books and numerous editions provide a developing or evolving notion of case study with more detailed accounts of the possible purposes of case study, followed by Merriam 1988 and Stake 1995 who wrestled with alternative ways of looking at purposes and the positioning of case study within potential disciplinary modes. The authors referenced in this section are often characterized as the foundational authors on this subject and may have published various editions of their work, cited elsewhere in this article, based on their shifting ideas or emphases.

Merriam, S. B. 1988. Case study research in education: A qualitative approach . San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

This is Merriam’s initial text on case study and is eminently accessible. The author establishes and reinforces various key features of case study; demonstrates support for positioning the case within a subject domain, e.g., psychology, sociology, etc.; and further shapes the case according to its purpose or intent.

Stake, R. E. 1995. The art of case study research . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

Stake is a very readable author, accessible and yet engaging with complex topics. The author establishes his key forms of case study: intrinsic, instrumental, and collective. Stake brings the reader through the process of conceptualizing the case, carrying it out, and analyzing the data. The author uses authentic examples to help readers understand and appreciate the nuances of an interpretive approach to case study.

Stenhouse, L. 1980. The study of samples and the study of cases. British Educational Research Journal 6:1–6.

DOI: 10.1080/0141192800060101

A key article in which Stenhouse sets out his stand on case study work. Those interested in the evolution of case study use in educational research should consider this article and the insights given.

Yin, R. K. 1984. Case Study Research: Design and Methods . Beverley Hills, CA: SAGE.

This preliminary text from Yin was very basic. However, it may be of interest in comparison with later books because Yin shows the ways in which case study as an approach or method in research has evolved in relation to detailed discussions of purpose, as well as the practicalities of working through the research process.

back to top

Users without a subscription are not able to see the full content on this page. Please subscribe or login .

Oxford Bibliographies Online is available by subscription and perpetual access to institutions. For more information or to contact an Oxford Sales Representative click here .

- About Education »

- Meet the Editorial Board »

- Academic Achievement

- Academic Audit for Universities

- Academic Freedom and Tenure in the United States

- Action Research in Education

- Adjuncts in Higher Education in the United States

- Administrator Preparation

- Adolescence

- Advanced Placement and International Baccalaureate Courses

- Advocacy and Activism in Early Childhood

- African American Racial Identity and Learning

- Alaska Native Education

- Alternative Certification Programs for Educators

- Alternative Schools

- American Indian Education

- Animals in Environmental Education

- Art Education

- Artificial Intelligence and Learning

- Assessing School Leader Effectiveness

- Assessment, Behavioral

- Assessment, Educational

- Assessment in Early Childhood Education

- Assistive Technology

- Augmented Reality in Education

- Beginning-Teacher Induction

- Bilingual Education and Bilingualism

- Black Undergraduate Women: Critical Race and Gender Perspe...

- Black Women in Academia

- Blended Learning

- Case Study in Education Research

- Changing Professional and Academic Identities

- Character Education

- Children’s and Young Adult Literature

- Children's Beliefs about Intelligence

- Children's Rights in Early Childhood Education

- Citizenship Education

- Civic and Social Engagement of Higher Education

- Classroom Learning Environments: Assessing and Investigati...

- Classroom Management

- Coherent Instructional Systems at the School and School Sy...

- College Admissions in the United States

- College Athletics in the United States

- Community Relations

- Comparative Education

- Computer-Assisted Language Learning

- Computer-Based Testing

- Conceptualizing, Measuring, and Evaluating Improvement Net...

- Continuous Improvement and "High Leverage" Educational Pro...

- Counseling in Schools

- Critical Approaches to Gender in Higher Education

- Critical Perspectives on Educational Innovation and Improv...

- Critical Race Theory

- Crossborder and Transnational Higher Education

- Cross-National Research on Continuous Improvement

- Cross-Sector Research on Continuous Learning and Improveme...

- Cultural Diversity in Early Childhood Education

- Culturally Responsive Leadership

- Culturally Responsive Pedagogies

- Culturally Responsive Teacher Education in the United Stat...

- Curriculum Design

- Data-driven Decision Making in the United States

- Deaf Education

- Desegregation and Integration

- Design Thinking and the Learning Sciences: Theoretical, Pr...

- Development, Moral

- Dialogic Pedagogy

- Digital Age Teacher, The

- Digital Citizenship

- Digital Divides

- Disabilities

- Distance Learning

- Distributed Leadership

- Doctoral Education and Training

- Early Childhood Education and Care (ECEC) in Denmark

- Early Childhood Education and Development in Mexico

- Early Childhood Education in Aotearoa New Zealand

- Early Childhood Education in Australia

- Early Childhood Education in China

- Early Childhood Education in Europe

- Early Childhood Education in Sub-Saharan Africa

- Early Childhood Education in Sweden

- Early Childhood Education Pedagogy

- Early Childhood Education Policy

- Early Childhood Education, The Arts in

- Early Childhood Mathematics

- Early Childhood Science

- Early Childhood Teacher Education

- Early Childhood Teachers in Aotearoa New Zealand

- Early Years Professionalism and Professionalization Polici...

- Economics of Education

- Education For Children with Autism

- Education for Sustainable Development

- Education Leadership, Empirical Perspectives in

- Education of Native Hawaiian Students

- Education Reform and School Change

- Educational Statistics for Longitudinal Research

- Educator Partnerships with Parents and Families with a Foc...

- Emotional and Affective Issues in Environmental and Sustai...

- Emotional and Behavioral Disorders

- English as an International Language for Academic Publishi...

- Environmental and Science Education: Overlaps and Issues

- Environmental Education

- Environmental Education in Brazil

- Epistemic Beliefs

- Equity and Improvement: Engaging Communities in Educationa...

- Equity, Ethnicity, Diversity, and Excellence in Education

- Ethical Research with Young Children

- Ethics and Education

- Ethics of Teaching

- Ethnic Studies

- Evidence-Based Communication Assessment and Intervention

- Family and Community Partnerships in Education

- Family Day Care

- Federal Government Programs and Issues

- Feminization of Labor in Academia

- Finance, Education

- Financial Aid

- Formative Assessment

- Future-Focused Education

- Gender and Achievement

- Gender and Alternative Education

- Gender, Power and Politics in the Academy

- Gender-Based Violence on University Campuses

- Gifted Education

- Global Mindedness and Global Citizenship Education

- Global University Rankings

- Governance, Education

- Grounded Theory

- Growth of Effective Mental Health Services in Schools in t...

- Higher Education and Globalization

- Higher Education and the Developing World

- Higher Education Faculty Characteristics and Trends in the...

- Higher Education Finance

- Higher Education Governance

- Higher Education Graduate Outcomes and Destinations

- Higher Education in Africa

- Higher Education in China

- Higher Education in Latin America

- Higher Education in the United States, Historical Evolutio...

- Higher Education, International Issues in

- Higher Education Management

- Higher Education Policy

- Higher Education Research

- Higher Education Student Assessment

- High-stakes Testing

- History of Early Childhood Education in the United States

- History of Education in the United States

- History of Technology Integration in Education

- Homeschooling

- Inclusion in Early Childhood: Difference, Disability, and ...

- Inclusive Education

- Indigenous Education in a Global Context

- Indigenous Learning Environments

- Indigenous Students in Higher Education in the United Stat...

- Infant and Toddler Pedagogy

- Inservice Teacher Education

- Integrating Art across the Curriculum

- Intelligence

- Intensive Interventions for Children and Adolescents with ...

- International Perspectives on Academic Freedom

- Intersectionality and Education

- Knowledge Development in Early Childhood

- Leadership Development, Coaching and Feedback for

- Leadership in Early Childhood Education

- Leadership Training with an Emphasis on the United States

- Learning Analytics in Higher Education

- Learning Difficulties

- Learning, Lifelong

- Learning, Multimedia

- Learning Strategies

- Legal Matters and Education Law

- LGBT Youth in Schools

- Linguistic Diversity

- Linguistically Inclusive Pedagogy

- Literacy Development and Language Acquisition

- Literature Reviews

- Mathematics Identity

- Mathematics Instruction and Interventions for Students wit...

- Mathematics Teacher Education

- Measurement for Improvement in Education

- Measurement in Education in the United States

- Meta-Analysis and Research Synthesis in Education

- Methodological Approaches for Impact Evaluation in Educati...

- Methodologies for Conducting Education Research

- Mindfulness, Learning, and Education

- Motherscholars

- Multiliteracies in Early Childhood Education

- Multiple Documents Literacy: Theory, Research, and Applica...

- Multivariate Research Methodology

- Museums, Education, and Curriculum

- Music Education

- Narrative Research in Education

- Native American Studies

- Nonformal and Informal Environmental Education

- Note-Taking

- Numeracy Education

- One-to-One Technology in the K-12 Classroom

- Online Education

- Open Education

- Organizing for Continuous Improvement in Education

- Organizing Schools for the Inclusion of Students with Disa...

- Outdoor Play and Learning

- Outdoor Play and Learning in Early Childhood Education

- Pedagogical Leadership

- Pedagogy of Teacher Education, A

- Performance Objectives and Measurement

- Performance-based Research Assessment in Higher Education

- Performance-based Research Funding

- Phenomenology in Educational Research

- Philosophy of Education

- Physical Education

- Podcasts in Education

- Policy Context of United States Educational Innovation and...

- Politics of Education

- Portable Technology Use in Special Education Programs and ...

- Post-humanism and Environmental Education

- Pre-Service Teacher Education

- Problem Solving

- Productivity and Higher Education

- Professional Development

- Professional Learning Communities

- Programs and Services for Students with Emotional or Behav...

- Psychology Learning and Teaching

- Psychometric Issues in the Assessment of English Language ...

- Qualitative Data Analysis Techniques

- Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Research Samp...

- Qualitative Research Design

- Quantitative Research Designs in Educational Research

- Queering the English Language Arts (ELA) Writing Classroom

- Race and Affirmative Action in Higher Education

- Reading Education

- Refugee and New Immigrant Learners

- Relational and Developmental Trauma and Schools

- Relational Pedagogies in Early Childhood Education

- Reliability in Educational Assessments

- Religion in Elementary and Secondary Education in the Unit...

- Researcher Development and Skills Training within the Cont...

- Research-Practice Partnerships in Education within the Uni...

- Response to Intervention

- Restorative Practices

- Risky Play in Early Childhood Education

- Scale and Sustainability of Education Innovation and Impro...

- Scaling Up Research-based Educational Practices

- School Accreditation

- School Choice

- School Culture

- School District Budgeting and Financial Management in the ...

- School Improvement through Inclusive Education

- School Reform

- Schools, Private and Independent

- School-Wide Positive Behavior Support

- Science Education

- Secondary to Postsecondary Transition Issues

- Self-Regulated Learning

- Self-Study of Teacher Education Practices

- Service-Learning

- Severe Disabilities

- Single Salary Schedule

- Single-sex Education

- Single-Subject Research Design

- Social Context of Education

- Social Justice

- Social Network Analysis

- Social Pedagogy

- Social Science and Education Research

- Social Studies Education

- Sociology of Education

- Standards-Based Education

- Statistical Assumptions

- Student Access, Equity, and Diversity in Higher Education

- Student Assignment Policy

- Student Engagement in Tertiary Education

- Student Learning, Development, Engagement, and Motivation ...

- Student Participation

- Student Voice in Teacher Development

- Sustainability Education in Early Childhood Education

- Sustainability in Early Childhood Education

- Sustainability in Higher Education

- Teacher Beliefs and Epistemologies

- Teacher Collaboration in School Improvement

- Teacher Evaluation and Teacher Effectiveness

- Teacher Preparation

- Teacher Training and Development

- Teacher Unions and Associations

- Teacher-Student Relationships

- Teaching Critical Thinking

- Technologies, Teaching, and Learning in Higher Education

- Technology Education in Early Childhood

- Technology, Educational

- Technology-based Assessment

- The Bologna Process

- The Regulation of Standards in Higher Education

- Theories of Educational Leadership

- Three Conceptions of Literacy: Media, Narrative, and Gamin...

- Tracking and Detracking

- Traditions of Quality Improvement in Education

- Transformative Learning

- Transitions in Early Childhood Education

- Tribally Controlled Colleges and Universities in the Unite...

- Understanding the Psycho-Social Dimensions of Schools and ...

- University Faculty Roles and Responsibilities in the Unite...

- Using Ethnography in Educational Research

- Value of Higher Education for Students and Other Stakehold...

- Virtual Learning Environments

- Vocational and Technical Education

- Wellness and Well-Being in Education

- Women's and Gender Studies

- Young Children and Spirituality

- Young Children's Learning Dispositions

- Young Children's Working Theories

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

Powered by:

- [185.80.149.115]

- 185.80.149.115

Search form

- About Faculty Development and Support

- Programs and Funding Opportunities

Consultations, Observations, and Services

- Strategic Resources & Digital Publications

- Canvas @ Yale Support

- Learning Environments @ Yale

- Teaching Workshops

- Teaching Consultations and Classroom Observations

- Teaching Programs

- Spring Teaching Forum

- Written and Oral Communication Workshops and Panels

- Writing Resources & Tutorials

- About the Graduate Writing Laboratory

- Writing and Public Speaking Consultations

- Writing Workshops and Panels

- Writing Peer-Review Groups

- Writing Retreats and All Writes

- Online Writing Resources for Graduate Students

- About Teaching Development for Graduate and Professional School Students

- Teaching Programs and Grants

- Teaching Forums

- Resources for Graduate Student Teachers

- About Undergraduate Writing and Tutoring

- Academic Strategies Program

- The Writing Center

- STEM Tutoring & Programs

- Humanities & Social Sciences

- Center for Language Study

- Online Course Catalog

- Antiracist Pedagogy

- NECQL 2019: NorthEast Consortium for Quantitative Literacy XXII Meeting

- STEMinar Series

- Teaching in Context: Troubling Times

- Helmsley Postdoctoral Teaching Scholars

- Pedagogical Partners

- Instructional Materials

- Evaluation & Research

- STEM Education Job Opportunities

- Yale Connect

- Online Education Legal Statements

You are here

Case-based learning.

Case-based learning (CBL) is an established approach used across disciplines where students apply their knowledge to real-world scenarios, promoting higher levels of cognition (see Bloom’s Taxonomy ). In CBL classrooms, students typically work in groups on case studies, stories involving one or more characters and/or scenarios. The cases present a disciplinary problem or problems for which students devise solutions under the guidance of the instructor. CBL has a strong history of successful implementation in medical, law, and business schools, and is increasingly used within undergraduate education, particularly within pre-professional majors and the sciences (Herreid, 1994). This method involves guided inquiry and is grounded in constructivism whereby students form new meanings by interacting with their knowledge and the environment (Lee, 2012).

There are a number of benefits to using CBL in the classroom. In a review of the literature, Williams (2005) describes how CBL: utilizes collaborative learning, facilitates the integration of learning, develops students’ intrinsic and extrinsic motivation to learn, encourages learner self-reflection and critical reflection, allows for scientific inquiry, integrates knowledge and practice, and supports the development of a variety of learning skills.

CBL has several defining characteristics, including versatility, storytelling power, and efficient self-guided learning. In a systematic analysis of 104 articles in health professions education, CBL was found to be utilized in courses with less than 50 to over 1000 students (Thistlethwaite et al., 2012). In these classrooms, group sizes ranged from 1 to 30, with most consisting of 2 to 15 students. Instructors varied in the proportion of time they implemented CBL in the classroom, ranging from one case spanning two hours of classroom time, to year-long case-based courses. These findings demonstrate that instructors use CBL in a variety of ways in their classrooms.

The stories that comprise the framework of case studies are also a key component to CBL’s effectiveness. Jonassen and Hernandez-Serrano (2002, p.66) describe how storytelling:

Is a method of negotiating and renegotiating meanings that allows us to enter into other’s realms of meaning through messages they utter in their stories,

Helps us find our place in a culture,

Allows us to explicate and to interpret, and

Facilitates the attainment of vicarious experience by helping us to distinguish the positive models to emulate from the negative model.

Neurochemically, listening to stories can activate oxytocin, a hormone that increases one’s sensitivity to social cues, resulting in more empathy, generosity, compassion and trustworthiness (Zak, 2013; Kosfeld et al., 2005). The stories within case studies serve as a means by which learners form new understandings through characters and/or scenarios.

CBL is often described in conjunction or in comparison with problem-based learning (PBL). While the lines are often confusingly blurred within the literature, in the most conservative of definitions, the features distinguishing the two approaches include that PBL involves open rather than guided inquiry, is less structured, and the instructor plays a more passive role. In PBL multiple solutions to the problem may exit, but the problem is often initially not well-defined. PBL also has a stronger emphasis on developing self-directed learning. The choice between implementing CBL versus PBL is highly dependent on the goals and context of the instruction. For example, in a comparison of PBL and CBL approaches during a curricular shift at two medical schools, students and faculty preferred CBL to PBL (Srinivasan et al., 2007). Students perceived CBL to be a more efficient process and more clinically applicable. However, in another context, PBL might be the favored approach.

In a review of the effectiveness of CBL in health profession education, Thistlethwaite et al. (2012), found several benefits:

Students enjoyed the method and thought it enhanced their learning,

Instructors liked how CBL engaged students in learning,

CBL seemed to facilitate small group learning, but the authors could not distinguish between whether it was the case itself or the small group learning that occurred as facilitated by the case.

Other studies have also reported on the effectiveness of CBL in achieving learning outcomes (Bonney, 2015; Breslin, 2008; Herreid, 2013; Krain, 2016). These findings suggest that CBL is a vehicle of engagement for instruction, and facilitates an environment whereby students can construct knowledge.

Science – Students are given a scenario to which they apply their basic science knowledge and problem-solving skills to help them solve the case. One example within the biological sciences is two brothers who have a family history of a genetic illness. They each have mutations within a particular sequence in their DNA. Students work through the case and draw conclusions about the biological impacts of these mutations using basic science. Sample cases: You are Not the Mother of Your Children ; Organic Chemisty and Your Cellphone: Organic Light-Emitting Diodes ; A Light on Physics: F-Number and Exposure Time

Medicine – Medical or pre-health students read about a patient presenting with specific symptoms. Students decide which questions are important to ask the patient in their medical history, how long they have experienced such symptoms, etc. The case unfolds and students use clinical reasoning, propose relevant tests, develop a differential diagnoses and a plan of treatment. Sample cases: The Case of the Crying Baby: Surgical vs. Medical Management ; The Plan: Ethics and Physician Assisted Suicide ; The Haemophilus Vaccine: A Victory for Immunologic Engineering

Public Health – A case study describes a pandemic of a deadly infectious disease. Students work through the case to identify Patient Zero, the person who was the first to spread the disease, and how that individual became infected. Sample cases: The Protective Parent ; The Elusive Tuberculosis Case: The CDC and Andrew Speaker ; Credible Voice: WHO-Beijing and the SARS Crisis

Law – A case study presents a legal dilemma for which students use problem solving to decide the best way to advise and defend a client. Students are presented information that changes during the case. Sample cases: Mortgage Crisis Call (abstract) ; The Case of the Unpaid Interns (abstract) ; Police-Community Dialogue (abstract)

Business – Students work on a case study that presents the history of a business success or failure. They apply business principles learned in the classroom and assess why the venture was successful or not. Sample cases: SELCO-Determining a path forward ; Project Masiluleke: Texting and Testing to Fight HIV/AIDS in South Africa ; Mayo Clinic: Design Thinking in Healthcare

Humanities - Students consider a case that presents a theater facing financial and management difficulties. They apply business and theater principles learned in the classroom to the case, working together to create solutions for the theater. Sample cases: David Geffen School of Drama

Recommendations

Finding and Writing Cases

Consider utilizing or adapting open access cases - The availability of open resources and databases containing cases that instructors can download makes this approach even more accessible in the classroom. Two examples of open databases are the Case Center on Public Leadership and Harvard Kennedy School (HKS) Case Program , which focus on government, leadership and public policy case studies.

- Consider writing original cases - In the event that an instructor is unable to find open access cases relevant to their course learning objectives, they may choose to write their own. See the following resources on case writing: Cooking with Betty Crocker: A Recipe for Case Writing ; The Way of Flesch: The Art of Writing Readable Cases ; Twixt Fact and Fiction: A Case Writer’s Dilemma ; And All That Jazz: An Essay Extolling the Virtues of Writing Case Teaching Notes .

Implementing Cases

Take baby steps if new to CBL - While entire courses and curricula may involve case-based learning, instructors who desire to implement on a smaller-scale can integrate a single case into their class, and increase the number of cases utilized over time as desired.

Use cases in classes that are small, medium or large - Cases can be scaled to any course size. In large classes with stadium seating, students can work with peers nearby, while in small classes with more flexible seating arrangements, teams can move their chairs closer together. CBL can introduce more noise (and energy) in the classroom to which an instructor often quickly becomes accustomed. Further, students can be asked to work on cases outside of class, and wrap up discussion during the next class meeting.

Encourage collaborative work - Cases present an opportunity for students to work together to solve cases which the historical literature supports as beneficial to student learning (Bruffee, 1993). Allow students to work in groups to answer case questions.

Form diverse teams as feasible - When students work within diverse teams they can be exposed to a variety of perspectives that can help them solve the case. Depending on the context of the course, priorities, and the background information gathered about the students enrolled in the class, instructors may choose to organize student groups to allow for diversity in factors such as current course grades, gender, race/ethnicity, personality, among other items.

Use stable teams as appropriate - If CBL is a large component of the course, a research-supported practice is to keep teams together long enough to go through the stages of group development: forming, storming, norming, performing and adjourning (Tuckman, 1965).

Walk around to guide groups - In CBL instructors serve as facilitators of student learning. Walking around allows the instructor to monitor student progress as well as identify and support any groups that may be struggling. Teaching assistants can also play a valuable role in supporting groups.

Interrupt strategically - Only every so often, for conversation in large group discussion of the case, especially when students appear confused on key concepts. An effective practice to help students meet case learning goals is to guide them as a whole group when the class is ready. This may include selecting a few student groups to present answers to discussion questions to the entire class, asking the class a question relevant to the case using polling software, and/or performing a mini-lesson on an area that appears to be confusing among students.

Assess student learning in multiple ways - Students can be assessed informally by asking groups to report back answers to various case questions. This practice also helps students stay on task, and keeps them accountable. Cases can also be included on exams using related scenarios where students are asked to apply their knowledge.

Barrows HS. (1996). Problem-based learning in medicine and beyond: a brief overview. New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 68, 3-12.

Bonney KM. (2015). Case Study Teaching Method Improves Student Performance and Perceptions of Learning Gains. Journal of Microbiology and Biology Education, 16(1): 21-28.

Breslin M, Buchanan, R. (2008) On the Case Study Method of Research and Teaching in Design. Design Issues, 24(1), 36-40.

Bruffee KS. (1993). Collaborative learning: Higher education, interdependence, and authority of knowledge. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, MD.

Herreid CF. (2013). Start with a Story: The Case Study Method of Teaching College Science, edited by Clyde Freeman Herreid. Originally published in 2006 by the National Science Teachers Association (NSTA); reprinted by the National Center for Case Study Teaching in Science (NCCSTS) in 2013.

Herreid CH. (1994). Case studies in science: A novel method of science education. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 23(4), 221–229.

Jonassen DH and Hernandez-Serrano J. (2002). Case-based reasoning and instructional design: Using stories to support problem solving. Educational Technology, Research and Development, 50(2), 65-77.

Kosfeld M, Heinrichs M, Zak PJ, Fischbacher U, Fehr E. (2005). Oxytocin increases trust in humans. Nature, 435, 673-676.

Krain M. (2016) Putting the learning in case learning? The effects of case-based approaches on student knowledge, attitudes, and engagement. Journal on Excellence in College Teaching, 27(2), 131-153.

Lee V. (2012). What is Inquiry-Guided Learning? New Directions for Learning, 129:5-14.

Nkhoma M, Sriratanaviriyakul N. (2017). Using case method to enrich students’ learning outcomes. Active Learning in Higher Education, 18(1):37-50.

Srinivasan et al. (2007). Comparing problem-based learning with case-based learning: Effects of a major curricular shift at two institutions. Academic Medicine, 82(1): 74-82.

Thistlethwaite JE et al. (2012). The effectiveness of case-based learning in health professional education. A BEME systematic review: BEME Guide No. 23. Medical Teacher, 34, e421-e444.

Tuckman B. (1965). Development sequence in small groups. Psychological Bulletin, 63(6), 384-99.

Williams B. (2005). Case-based learning - a review of the literature: is there scope for this educational paradigm in prehospital education? Emerg Med, 22, 577-581.

Zak, PJ (2013). How Stories Change the Brain. Retrieved from: https://greatergood.berkeley.edu/article/item/how_stories_change_brain

YOU MAY BE INTERESTED IN

Reserve a Room

The Poorvu Center for Teaching and Learning partners with departments and groups on-campus throughout the year to share its space. Please review the reservation form and submit a request.

Instructional Enhancement Fund

The Instructional Enhancement Fund (IEF) awards grants of up to $500 to support the timely integration of new learning activities into an existing undergraduate or graduate course. All Yale instructors of record, including tenured and tenure-track faculty, clinical instructional faculty, lecturers, lectors, and part-time acting instructors (PTAIs), are eligible to apply. Award decisions are typically provided within two weeks to help instructors implement ideas for the current semester.

The Poorvu Center for Teaching and Learning routinely supports members of the Yale community with individual instructional consultations and classroom observations.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- What Is a Case Study? | Definition, Examples & Methods

What Is a Case Study? | Definition, Examples & Methods

Published on May 8, 2019 by Shona McCombes . Revised on November 20, 2023.

A case study is a detailed study of a specific subject, such as a person, group, place, event, organization, or phenomenon. Case studies are commonly used in social, educational, clinical, and business research.

A case study research design usually involves qualitative methods , but quantitative methods are sometimes also used. Case studies are good for describing , comparing, evaluating and understanding different aspects of a research problem .

Table of contents

When to do a case study, step 1: select a case, step 2: build a theoretical framework, step 3: collect your data, step 4: describe and analyze the case, other interesting articles.

A case study is an appropriate research design when you want to gain concrete, contextual, in-depth knowledge about a specific real-world subject. It allows you to explore the key characteristics, meanings, and implications of the case.

Case studies are often a good choice in a thesis or dissertation . They keep your project focused and manageable when you don’t have the time or resources to do large-scale research.

You might use just one complex case study where you explore a single subject in depth, or conduct multiple case studies to compare and illuminate different aspects of your research problem.

| Research question | Case study |

|---|---|

| What are the ecological effects of wolf reintroduction? | Case study of wolf reintroduction in Yellowstone National Park |

| How do populist politicians use narratives about history to gain support? | Case studies of Hungarian prime minister Viktor Orbán and US president Donald Trump |

| How can teachers implement active learning strategies in mixed-level classrooms? | Case study of a local school that promotes active learning |

| What are the main advantages and disadvantages of wind farms for rural communities? | Case studies of three rural wind farm development projects in different parts of the country |

| How are viral marketing strategies changing the relationship between companies and consumers? | Case study of the iPhone X marketing campaign |

| How do experiences of work in the gig economy differ by gender, race and age? | Case studies of Deliveroo and Uber drivers in London |

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

Once you have developed your problem statement and research questions , you should be ready to choose the specific case that you want to focus on. A good case study should have the potential to:

- Provide new or unexpected insights into the subject

- Challenge or complicate existing assumptions and theories

- Propose practical courses of action to resolve a problem

- Open up new directions for future research

TipIf your research is more practical in nature and aims to simultaneously investigate an issue as you solve it, consider conducting action research instead.

Unlike quantitative or experimental research , a strong case study does not require a random or representative sample. In fact, case studies often deliberately focus on unusual, neglected, or outlying cases which may shed new light on the research problem.

Example of an outlying case studyIn the 1960s the town of Roseto, Pennsylvania was discovered to have extremely low rates of heart disease compared to the US average. It became an important case study for understanding previously neglected causes of heart disease.

However, you can also choose a more common or representative case to exemplify a particular category, experience or phenomenon.

Example of a representative case studyIn the 1920s, two sociologists used Muncie, Indiana as a case study of a typical American city that supposedly exemplified the changing culture of the US at the time.

While case studies focus more on concrete details than general theories, they should usually have some connection with theory in the field. This way the case study is not just an isolated description, but is integrated into existing knowledge about the topic. It might aim to:

- Exemplify a theory by showing how it explains the case under investigation

- Expand on a theory by uncovering new concepts and ideas that need to be incorporated

- Challenge a theory by exploring an outlier case that doesn’t fit with established assumptions

To ensure that your analysis of the case has a solid academic grounding, you should conduct a literature review of sources related to the topic and develop a theoretical framework . This means identifying key concepts and theories to guide your analysis and interpretation.

There are many different research methods you can use to collect data on your subject. Case studies tend to focus on qualitative data using methods such as interviews , observations , and analysis of primary and secondary sources (e.g., newspaper articles, photographs, official records). Sometimes a case study will also collect quantitative data.

Example of a mixed methods case studyFor a case study of a wind farm development in a rural area, you could collect quantitative data on employment rates and business revenue, collect qualitative data on local people’s perceptions and experiences, and analyze local and national media coverage of the development.

The aim is to gain as thorough an understanding as possible of the case and its context.

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

In writing up the case study, you need to bring together all the relevant aspects to give as complete a picture as possible of the subject.

How you report your findings depends on the type of research you are doing. Some case studies are structured like a standard scientific paper or thesis , with separate sections or chapters for the methods , results and discussion .

Others are written in a more narrative style, aiming to explore the case from various angles and analyze its meanings and implications (for example, by using textual analysis or discourse analysis ).

In all cases, though, make sure to give contextual details about the case, connect it back to the literature and theory, and discuss how it fits into wider patterns or debates.

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Normal distribution

- Degrees of freedom

- Null hypothesis

- Discourse analysis

- Control groups

- Mixed methods research

- Non-probability sampling

- Quantitative research

- Ecological validity

Research bias

- Rosenthal effect

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Selection bias

- Negativity bias

- Status quo bias

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, November 20). What Is a Case Study? | Definition, Examples & Methods. Scribbr. Retrieved August 3, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/case-study/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, primary vs. secondary sources | difference & examples, what is a theoretical framework | guide to organizing, what is action research | definition & examples, "i thought ai proofreading was useless but..".

I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes”

Using Case Studies to Teach

Why Use Cases?

Many students are more inductive than deductive reasoners, which means that they learn better from examples than from logical development starting with basic principles. The use of case studies can therefore be a very effective classroom technique.

Case studies are have long been used in business schools, law schools, medical schools and the social sciences, but they can be used in any discipline when instructors want students to explore how what they have learned applies to real world situations. Cases come in many formats, from a simple “What would you do in this situation?” question to a detailed description of a situation with accompanying data to analyze. Whether to use a simple scenario-type case or a complex detailed one depends on your course objectives.

Most case assignments require students to answer an open-ended question or develop a solution to an open-ended problem with multiple potential solutions. Requirements can range from a one-paragraph answer to a fully developed group action plan, proposal or decision.

Common Case Elements

Most “full-blown” cases have these common elements:

- A decision-maker who is grappling with some question or problem that needs to be solved.

- A description of the problem’s context (a law, an industry, a family).

- Supporting data, which can range from data tables to links to URLs, quoted statements or testimony, supporting documents, images, video, or audio.

Case assignments can be done individually or in teams so that the students can brainstorm solutions and share the work load.

The following discussion of this topic incorporates material presented by Robb Dixon of the School of Management and Rob Schadt of the School of Public Health at CEIT workshops. Professor Dixon also provided some written comments that the discussion incorporates.

Advantages to the use of case studies in class

A major advantage of teaching with case studies is that the students are actively engaged in figuring out the principles by abstracting from the examples. This develops their skills in:

- Problem solving

- Analytical tools, quantitative and/or qualitative, depending on the case

- Decision making in complex situations

- Coping with ambiguities

Guidelines for using case studies in class

In the most straightforward application, the presentation of the case study establishes a framework for analysis. It is helpful if the statement of the case provides enough information for the students to figure out solutions and then to identify how to apply those solutions in other similar situations. Instructors may choose to use several cases so that students can identify both the similarities and differences among the cases.

Depending on the course objectives, the instructor may encourage students to follow a systematic approach to their analysis. For example:

- What is the issue?

- What is the goal of the analysis?

- What is the context of the problem?

- What key facts should be considered?

- What alternatives are available to the decision-maker?

- What would you recommend — and why?

An innovative approach to case analysis might be to have students role-play the part of the people involved in the case. This not only actively engages students, but forces them to really understand the perspectives of the case characters. Videos or even field trips showing the venue in which the case is situated can help students to visualize the situation that they need to analyze.

Accompanying Readings

Case studies can be especially effective if they are paired with a reading assignment that introduces or explains a concept or analytical method that applies to the case. The amount of emphasis placed on the use of the reading during the case discussion depends on the complexity of the concept or method. If it is straightforward, the focus of the discussion can be placed on the use of the analytical results. If the method is more complex, the instructor may need to walk students through its application and the interpretation of the results.

Leading the Case Discussion and Evaluating Performance

Decision cases are more interesting than descriptive ones. In order to start the discussion in class, the instructor can start with an easy, noncontroversial question that all the students should be able to answer readily. However, some of the best case discussions start by forcing the students to take a stand. Some instructors will ask a student to do a formal “open” of the case, outlining his or her entire analysis. Others may choose to guide discussion with questions that move students from problem identification to solutions. A skilled instructor steers questions and discussion to keep the class on track and moving at a reasonable pace.

In order to motivate the students to complete the assignment before class as well as to stimulate attentiveness during the class, the instructor should grade the participation—quantity and especially quality—during the discussion of the case. This might be a simple check, check-plus, check-minus or zero. The instructor should involve as many students as possible. In order to engage all the students, the instructor can divide them into groups, give each group several minutes to discuss how to answer a question related to the case, and then ask a randomly selected person in each group to present the group’s answer and reasoning. Random selection can be accomplished through rolling of dice, shuffled index cards, each with one student’s name, a spinning wheel, etc.

Tips on the Penn State U. website: https://sites.psu.edu/pedagogicalpractices/case-studies/

If you are interested in using this technique in a science course, there is a good website on use of case studies in the sciences at the National Science Teaching Association.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- J Microbiol Biol Educ

- v.16(1); 2015 May

Case Study Teaching Method Improves Student Performance and Perceptions of Learning Gains †

Associated data.

- Appendix 1: Example assessment questions used to assess the effectiveness of case studies at promoting learning

- Appendix 2: Student learning gains were assessed using a modified version of the SALG course evaluation tool

Following years of widespread use in business and medical education, the case study teaching method is becoming an increasingly common teaching strategy in science education. However, the current body of research provides limited evidence that the use of published case studies effectively promotes the fulfillment of specific learning objectives integral to many biology courses. This study tested the hypothesis that case studies are more effective than classroom discussions and textbook reading at promoting learning of key biological concepts, development of written and oral communication skills, and comprehension of the relevance of biological concepts to everyday life. This study also tested the hypothesis that case studies produced by the instructor of a course are more effective at promoting learning than those produced by unaffiliated instructors. Additionally, performance on quantitative learning assessments and student perceptions of learning gains were analyzed to determine whether reported perceptions of learning gains accurately reflect academic performance. The results reported here suggest that case studies, regardless of the source, are significantly more effective than other methods of content delivery at increasing performance on examination questions related to chemical bonds, osmosis and diffusion, mitosis and meiosis, and DNA structure and replication. This finding was positively correlated to increased student perceptions of learning gains associated with oral and written communication skills and the ability to recognize connections between biological concepts and other aspects of life. Based on these findings, case studies should be considered as a preferred method for teaching about a variety of concepts in science courses.

INTRODUCTION

The case study teaching method is a highly adaptable style of teaching that involves problem-based learning and promotes the development of analytical skills ( 8 ). By presenting content in the format of a narrative accompanied by questions and activities that promote group discussion and solving of complex problems, case studies facilitate development of the higher levels of Bloom’s taxonomy of cognitive learning; moving beyond recall of knowledge to analysis, evaluation, and application ( 1 , 9 ). Similarly, case studies facilitate interdisciplinary learning and can be used to highlight connections between specific academic topics and real-world societal issues and applications ( 3 , 9 ). This has been reported to increase student motivation to participate in class activities, which promotes learning and increases performance on assessments ( 7 , 16 , 19 , 23 ). For these reasons, case-based teaching has been widely used in business and medical education for many years ( 4 , 11 , 12 , 14 ). Although case studies were considered a novel method of science education just 20 years ago, the case study teaching method has gained popularity in recent years among an array of scientific disciplines such as biology, chemistry, nursing, and psychology ( 5 – 7 , 9 , 11 , 13 , 15 – 17 , 21 , 22 , 24 ).

Although there is now a substantive and growing body of literature describing how to develop and use case studies in science teaching, current research on the effectiveness of case study teaching at meeting specific learning objectives is of limited scope and depth. Studies have shown that working in groups during completion of case studies significantly improves student perceptions of learning and may increase performance on assessment questions, and that the use of clickers can increase student engagement in case study activities, particularly among non-science majors, women, and freshmen ( 7 , 21 , 22 ). Case study teaching has been shown to improve exam performance in an anatomy and physiology course, increasing the mean score across all exams given in a two-semester sequence from 66% to 73% ( 5 ). Use of case studies was also shown to improve students’ ability to synthesize complex analytical questions about the real-world issues associated with a scientific topic ( 6 ). In a high school chemistry course, it was demonstrated that the case study teaching method produces significant increases in self-reported control of learning, task value, and self-efficacy for learning and performance ( 24 ). This effect on student motivation is important because enhanced motivation for learning activities has been shown to promote student engagement and academic performance ( 19 , 24 ). Additionally, faculty from a number of institutions have reported that using case studies promotes critical thinking, learning, and participation among students, especially in terms of the ability to view an issue from multiple perspectives and to grasp the practical application of core course concepts ( 23 ).

Despite what is known about the effectiveness of case studies in science education, questions remain about the functionality of the case study teaching method at promoting specific learning objectives that are important to many undergraduate biology courses. A recent survey of teachers who use case studies found that the topics most often covered in general biology courses included genetics and heredity, cell structure, cells and energy, chemistry of life, and cell cycle and cancer, suggesting that these topics should be of particular interest in studies that examine the effectiveness of the case study teaching method ( 8 ). However, the existing body of literature lacks direct evidence that the case study method is an effective tool for teaching about this collection of important topics in biology courses. Further, the extent to which case study teaching promotes development of science communication skills and the ability to understand the connections between biological concepts and everyday life has not been examined, yet these are core learning objectives shared by a variety of science courses. Although many instructors have produced case studies for use in their own classrooms, the production of novel case studies is time-consuming and requires skills that not all instructors have perfected. It is therefore important to determine whether case studies published by instructors who are unaffiliated with a particular course can be used effectively and obviate the need for each instructor to develop new case studies for their own courses. The results reported herein indicate that teaching with case studies results in significantly higher performance on examination questions about chemical bonds, osmosis and diffusion, mitosis and meiosis, and DNA structure and replication than that achieved by class discussions and textbook reading for topics of similar complexity. Case studies also increased overall student perceptions of learning gains and perceptions of learning gains specifically related to written and oral communication skills and the ability to grasp connections between scientific topics and their real-world applications. The effectiveness of the case study teaching method at increasing academic performance was not correlated to whether the case study used was authored by the instructor of the course or by an unaffiliated instructor. These findings support increased use of published case studies in the teaching of a variety of biological concepts and learning objectives.

Student population

This study was conducted at Kingsborough Community College, which is part of the City University of New York system, located in Brooklyn, New York. Kingsborough Community College has a diverse population of approximately 19,000 undergraduate students. The student population included in this study was enrolled in the first semester of a two-semester sequence of general (introductory) biology for biology majors during the spring, winter, or summer semester of 2014. A total of 63 students completed the course during this time period; 56 students consented to the inclusion of their data in the study. Of the students included in the study, 23 (41%) were male and 33 (59%) were female; 40 (71%) were registered as college freshmen and 16 (29%) were registered as college sophomores. To normalize participant groups, the same student population pooled from three classes taught by the same instructor was used to assess both experimental and control teaching methods.

Course material

The four biological concepts assessed during this study (chemical bonds, osmosis and diffusion, mitosis and meiosis, and DNA structure and replication) were selected as topics for studying the effectiveness of case study teaching because they were the key concepts addressed by this particular course that were most likely to be taught in a number of other courses, including biology courses for both majors and nonmajors at outside institutions. At the start of this study, relevant existing case studies were freely available from the National Center for Case Study Teaching in Science (NCCSTS) to address mitosis and meiosis and DNA structure and replication, but published case studies that appropriately addressed chemical bonds and osmosis and diffusion were not available. Therefore, original case studies that addressed the latter two topics were produced as part of this study, and case studies produced by unaffiliated instructors and published by the NCCSTS were used to address the former two topics. By the conclusion of this study, all four case studies had been peer-reviewed and accepted for publication by the NCCSTS ( http://sciencecases.lib.buffalo.edu/cs/ ). Four of the remaining core topics covered in this course (macromolecules, photosynthesis, genetic inheritance, and translation) were selected as control lessons to provide control assessment data.

To minimize extraneous variation, control topics and assessments were carefully matched in complexity, format, and number with case studies, and an equal amount of class time was allocated for each case study and the corresponding control lesson. Instruction related to control lessons was delivered using minimal slide-based lectures, with emphasis on textbook reading assignments accompanied by worksheets completed by students in and out of the classroom, and small and large group discussion of key points. Completion of activities and discussion related to all case studies and control topics that were analyzed was conducted in the classroom, with the exception of the take-home portion of the osmosis and diffusion case study.

Data collection and analysis

This study was performed in accordance with a protocol approved by the Kingsborough Community College Human Research Protection Program and the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the City University of New York (CUNY IRB reference 539938-1; KCC IRB application #: KCC 13-12-126-0138). Assessment scores were collected from regularly scheduled course examinations. For each case study, control questions were included on the same examination that were similar in number, format, point value, and difficulty level, but related to a different topic covered in the course that was of similar complexity. Complexity and difficulty of both case study and control questions were evaluated using experiential data from previous iterations of the course; the Bloom’s taxonomy designation and amount of material covered by each question, as well as the average score on similar questions achieved by students in previous iterations of the course was considered in determining appropriate controls. All assessment questions were scored using a standardized, pre-determined rubric. Student perceptions of learning gains were assessed using a modified version of the Student Assessment of Learning Gains (SALG) course evaluation tool ( http://www.salgsite.org ), distributed in hardcopy and completed anonymously during the last week of the course. Students were presented with a consent form to opt-in to having their data included in the data analysis. After the course had concluded and final course grades had been posted, data from consenting students were pooled in a database and identifying information was removed prior to analysis. Statistical analysis of data was conducted using the Kruskal-Wallis one-way analysis of variance and calculation of the R 2 coefficient of determination.

Teaching with case studies improves performance on learning assessments, independent of case study origin

To evaluate the effectiveness of the case study teaching method at promoting learning, student performance on examination questions related to material covered by case studies was compared with performance on questions that covered material addressed through classroom discussions and textbook reading. The latter questions served as control items; assessment items for each case study were compared with control items that were of similar format, difficulty, and point value ( Appendix 1 ). Each of the four case studies resulted in an increase in examination performance compared with control questions that was statistically significant, with an average difference of 18% ( Fig. 1 ). The mean score on case study-related questions was 73% for the chemical bonds case study, 79% for osmosis and diffusion, 76% for mitosis and meiosis, and 70% for DNA structure and replication ( Fig. 1 ). The mean score for non-case study-related control questions was 60%, 54%, 60%, and 52%, respectively ( Fig. 1 ). In terms of examination performance, no significant difference between case studies produced by the instructor of the course (chemical bonds and osmosis and diffusion) and those produced by unaffiliated instructors (mitosis and meiosis and DNA structure and replication) was indicated by the Kruskal-Wallis one-way analysis of variance. However, the 25% difference between the mean score on questions related to the osmosis and diffusion case study and the mean score on the paired control questions was notably higher than the 13–18% differences observed for the other case studies ( Fig. 1 ).

Case study teaching method increases student performance on examination questions. Mean score on a set of examination questions related to lessons covered by case studies (black bars) and paired control questions of similar format and difficulty about an unrelated topic (white bars). Chemical bonds, n = 54; Osmosis and diffusion, n = 54; Mitosis and meiosis, n = 51; DNA structure and replication, n = 50. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean (SEM). Asterisk indicates p < 0.05.

Case study teaching increases student perception of learning gains related to core course objectives

Student learning gains were assessed using a modified version of the SALG course evaluation tool ( Appendix 2 ). To determine whether completing case studies was more effective at increasing student perceptions of learning gains than completing textbook readings or participating in class discussions, perceptions of student learning gains for each were compared. In response to the question “Overall, how much did each of the following aspects of the class help your learning?” 82% of students responded that case studies helped a “good” or “great” amount, compared with 70% for participating in class discussions and 58% for completing textbook reading; only 4% of students responded that case studies helped a “small amount” or “provided no help,” compared with 2% for class discussions and 22% for textbook reading ( Fig. 2A ). The differences in reported learning gains derived from the use of case studies compared with class discussion and textbook readings were statistically significant, while the difference in learning gains associated with class discussion compared with textbook reading was not statistically significant by a narrow margin ( p = 0.051).