- Link to facebook

- Link to linkedin

- Link to twitter

- Link to youtube

- Writing Tips

A Guide to Rebuttals in Argumentative Essays

4-minute read

- 27th May 2023

Rebuttals are an essential part of a strong argument. But what are they, exactly, and how can you use them effectively? Read on to find out.

What Is a Rebuttal?

When writing an argumentative essay , there’s always an opposing point of view. You can’t present an argument without the possibility of someone disagreeing.

Sure, you could just focus on your argument and ignore the other perspective, but that weakens your essay. Coming up with possible alternative points of view, or counterarguments, and being prepared to address them, gives you an edge. A rebuttal is your response to these opposing viewpoints.

How Do Rebuttals Work?

With a rebuttal, you can take the fighting power away from any opposition to your idea before they have a chance to attack. For a rebuttal to work, it needs to follow the same formula as the other key points in your essay: it should be researched, developed, and presented with evidence.

Rebuttals in Action

Suppose you’re writing an essay arguing that strawberries are the best fruit. A potential counterargument could be that strawberries don’t work as well in baked goods as other berries do, as they can get soggy and lose some of their flavor. Your rebuttal would state this point and then explain why it’s not valid:

Read on for a few simple steps to formulating an effective rebuttal.

Step 1. Come up with a Counterargument

A strong rebuttal is only possible when there’s a strong counterargument. You may be convinced of your idea but try to place yourself on the other side. Rather than addressing weak opposing views that are easy to fend off, try to come up with the strongest claims that could be made.

In your essay, explain the counterargument and agree with it. That’s right, agree with it – to an extent. State why there’s some truth to it and validate the concerns it presents.

Step 2. Point Out Its Flaws

Now that you’ve presented a counterargument, poke holes in it . To do so, analyze the argument carefully and notice if there are any biases or caveats that weaken it. Looking at the claim that strawberries don’t work well in baked goods, a weakness could be that this argument only applies when strawberries are baked in a pie.

Find this useful?

Subscribe to our newsletter and get writing tips from our editors straight to your inbox.

Step 3. Present New Points

Once you reveal the counterargument’s weakness, present a new perspective, and provide supporting evidence to show that your argument is still the correct one. This means providing new points that the opposer may not have considered when presenting their claim.

Offering new ideas that weaken a counterargument makes you come off as authoritative and informed, which will make your readers more likely to agree with you.

Summary: Rebuttals

Rebuttals are essential when presenting an argument. Even if a counterargument is stronger than your point, you can construct an effective rebuttal that stands a chance against it.

We hope this guide helps you to structure and format your argumentative essay . And once you’ve finished writing, send a copy to our expert editors. We’ll ensure perfect grammar, spelling, punctuation, referencing, and more. Try it out for free today!

Frequently Asked Questions

What is a rebuttal in an essay.

A rebuttal is a response to a counterargument. It presents the potential counterclaim, discusses why it could be valid, and then explains why the original argument is still correct.

How do you form an effective rebuttal?

To use rebuttals effectively, come up with a strong counterclaim and respectfully point out its weaknesses. Then present new ideas that fill those gaps and strengthen your point.

Share this article:

Post A New Comment

Got content that needs a quick turnaround? Let us polish your work. Explore our editorial business services.

5-minute read

Free Email Newsletter Template

Promoting a brand means sharing valuable insights to connect more deeply with your audience, and...

6-minute read

How to Write a Nonprofit Grant Proposal

If you’re seeking funding to support your charitable endeavors as a nonprofit organization, you’ll need...

9-minute read

How to Use Infographics to Boost Your Presentation

Is your content getting noticed? Capturing and maintaining an audience’s attention is a challenge when...

8-minute read

Why Interactive PDFs Are Better for Engagement

Are you looking to enhance engagement and captivate your audience through your professional documents? Interactive...

7-minute read

Seven Key Strategies for Voice Search Optimization

Voice search optimization is rapidly shaping the digital landscape, requiring content professionals to adapt their...

Five Creative Ways to Showcase Your Digital Portfolio

Are you a creative freelancer looking to make a lasting impression on potential clients or...

Make sure your writing is the best it can be with our expert English proofreading and editing.

- Humanities ›

- English Grammar ›

Usage and Examples of a Rebuttal

Weakening an Opponent's Claim With Facts

David Hume Kennerly/Wikimedia Commons/Public Domain

- An Introduction to Punctuation

- Ph.D., Rhetoric and English, University of Georgia

- M.A., Modern English and American Literature, University of Leicester

- B.A., English, State University of New York

A rebuttal takes on a couple of different forms. As it pertains to an argument or debate, the definition of a rebuttal is the presentation of evidence and reasoning meant to weaken or undermine an opponent's claim. However, in persuasive speaking, a rebuttal is typically part of a discourse with colleagues and rarely a stand-alone speech.

Rebuttals are used in law, public affairs, and politics, and they're in the thick of effective public speaking. They also can be found in academic publishing, editorials, letters to the editor, formal responses to personnel matters, or customer service complaints/reviews. A rebuttal is also called a counterargument.

Types and Occurrences of Rebuttals

Rebuttals can come into play during any kind of argument or occurrence where someone has to defend a position contradictory to another opinion presented. Evidence backing up the rebuttal position is key.

Formally, students use rebuttal in debate competitions. In this arena, rebuttals don't make new arguments , just battle the positions already presented in a specific, timed format. For example, a rebuttal may get four minutes after an argument is presented in eight.

In academic publishing, an author presents an argument in a paper, such as on a work of literature, stating why it should be seen in a particular light. A rebuttal letter about the paper can find the flaws in the argument and evidence cited, and present contradictory evidence. If a writer of a paper has the paper rejected for publishing by the journal, a well-crafted rebuttal letter can give further evidence of the quality of the work and the due diligence taken to come up with the thesis or hypothesis.

In law, an attorney can present a rebuttal witness to show that a witness on the other side is in error. For example, after the defense has presented its case, the prosecution can present rebuttal witnesses. This is new evidence only and witnesses that contradict defense witness testimony. An effective rebuttal to a closing argument in a trial can leave enough doubt in the jury's minds to have a defendant found not guilty.

In public affairs and politics, people can argue points in front of the local city council or even speak in front of their state government. Our representatives in Washington present diverging points of view on bills up for debate . Citizens can argue policy and present rebuttals in the opinion pages of the newspaper.

On the job, if a person has a complaint brought against him to the human resources department, that employee has a right to respond and tell his or her side of the story in a formal procedure, such as a rebuttal letter.

In business, if a customer leaves a poor review of service or products on a website, the company's owner or a manager will, at minimum, need to diffuse the situation by apologizing and offering a concession for goodwill. But in some cases, a business needs to be defended. Maybe the irate customer left out of the complaint the fact that she was inebriated and screaming at the top of her lungs when she was asked to leave the shop. Rebuttals in these types of instances need to be delicately and objectively phrased.

Characteristics of an Effective Rebuttal

"If you disagree with a comment, explain the reason," says Tim Gillespie in "Doing Literary Criticism." He notes that "mocking, scoffing, hooting, or put-downs reflect poorly on your character and on your point of view. The most effective rebuttal to an opinion with which you strongly disagree is an articulate counterargument."

Rebuttals that rely on facts are also more ethical than those that rely solely on emotion or diversion from the topic through personal attacks on the opponent. That is the arena where politics, for example, can stray from trying to communicate a message into becoming a reality show.

With evidence as the central focal point, a good rebuttal relies on several elements to win an argument, including a clear presentation of the counterclaim, recognizing the inherent barrier standing in the way of the listener accepting the statement as truth, and presenting evidence clearly and concisely while remaining courteous and highly rational.

The evidence, as a result, must do the bulk work of proving the argument while the speaker should also preemptively defend certain erroneous attacks the opponent might make against it.

That is not to say that a rebuttal can't have an emotional element, as long as it works with evidence. A statistic about the number of people filing for bankruptcy per year due to medical debt can pair with a story of one such family as an example to support the topic of health care reform. It's both illustrative — a more personal way to talk about dry statistics — and an appeal to emotions.

To prepare an effective rebuttal, you need to know your opponent's position thoroughly to be able to formulate the proper attacks and to find evidence that dismantles the validity of that viewpoint. The first speaker will also anticipate your position and will try to make it look erroneous.

You will need to show:

- Contradictions in the first argument

- Terminology that's used in a way in order to sway opinion ( bias ) or used incorrectly. For example, when polls were taken about "Obamacare," people who didn't view the president favorably were more likely to want the policy defeated than when the actual name of it was presented as the Affordable Care Act.

- Errors in cause and effect

- Poor sources or misplaced authority

- Examples in the argument that are flawed or not comprehensive enough

- Flaws in the assumptions that the argument is based on

- Claims in the argument that are without proof or are widely accepted without actual proof. For example, alcoholism is defined by society as a disease. However, there isn't irrefutable medical proof that it is a disease like diabetes, for instance. Alcoholism manifests itself more like behavioral disorders, which are psychological.

The more points in the argument that you can dismantle, the more effective your rebuttal. Keep track of them as they're presented in the argument, and go after as many of them as you can.

Refutation Definition

The word rebuttal can be used interchangeably with refutation , which includes any contradictory statement in an argument. Strictly speaking, the distinction between the two is that a rebuttal must provide evidence, whereas a refutation merely relies on a contrary opinion. They differ in legal and argumentation contexts, wherein refutation involves any counterargument, while rebuttals rely on contradictory evidence to provide a means for a counterargument.

A successful refutation may disprove evidence with reasoning, but rebuttals must present evidence.

- the dozens (game of insults)

- Definition of Usage Labels and Notes in English Dictionaries

- Affect vs. Effect: How to Choose the Right Word

- What Is Aphesis?

- Definition and Examples of Praeteritio (Preteritio) in Rhetoric

- The Difference Between Portentous and Pretentious

- Advisor vs. Adviser: How to Choose the Right Word

- What Is a Compound Verb?

- Solecism in English

- The Difference Between "Leave" and "Let"

- The Commonly Confused Verbs Shall and Will

- Levels of Usage: Definition and Examples

- Defining Grammar

- The Commonly Confused Words Prescribe and Proscribe

- What's the Difference Between 'Baited' and 'Bated'?

- Customer Reviews

- Extended Essays

- IB Internal Assessment

- Theory of Knowledge

- Literature Review

- Dissertations

Essay Writing

- Research Writing

- Assignment Help

- Capstone Projects

- College Application

- Online Class

What is Rebuttal in an Argumentative Essay?

0 comments

Even if you have the most convincing evidence and reasons to explain your position on an issue, there will still be people in your audience who will not agree with you.

Usually, this creates an opportunity for counterclaims, which requires a response through rebuttal. So what exactly is rebuttal in an argumentative essay?

A rebuttal in an argumentative essay is a response you give to your opponent’s argument to show that the position they currently hold on an issue is wrong. While you agree with their counterargument, you point out the flaws using the strongest piece of evidence to strengthen your position.

To be clear, it’s hard to write an argument on an issue without considering counterclaim and rebuttals in the first place.

If you think about it, debatable topics require a consideration of both sides of an issue, which is why it’s important to learn about counterclaims and rebuttals in argumentative writing.

What is a Counterclaim in an Argument?

To understand why rebuttal comes into play in an argumentative essay, you first have to know what a counterclaim is and why it’s important in writing.

A counterclaim is an argument that an opponent makes to weaken your thesis. In particular, counterarguments try to show why your argument’s claim is wrong and try to propose an alternative to what you stand for.

From a writing standpoint, you have to recognize the counterclaims presented by the opposing side.

In fact, argumentative writing requires you to look at the two sides of an issue even if you’ve already taken a strong stance on it.

There are a number of benefits of including counterarguments in your argumentative essay:

- It shows your instructor that you’ve looked into both sides of the argument and recognize that some readers may not share your views initially.

- You create an opportunity to provide a strong rebuttal to the counterclaims, so readers see them before they finish reading the essay.

- You end up strengthening your writing because the essay turns out more objective than it would without recognizing the counterclaims from the opposing side.

What is Rebuttal in Argumentative Essay?

Your opponent will always look for weaknesses in your argument and try the best they can to show that you’re wrong.

Since you have solid grounds that your stance on an issue is reasonable, truthful, or more meaningful, you have to give a solid response to the opposition.

This is where rebuttal comes in.

In argumentative writing, rebuttal refers to the answer you give directly to an opponent in response to their counterargument. The answer should be a convincing explanation that shows an opponent why and/or how they’re wrong on an issue.

How to Write a Rebuttal Paragraph in Argumentative Essay

Now that you understand the connection between a counterclaim and rebuttal in an argumentative writing, let’s look at some approaches that you can use to refute your opponent’s arguments.

1. Point Out the Errors in the Counterargument

You’ve taken a stance on an issue for a reason, and mostly it’s because you believe yours is the most reasonable position based on the data, statistics, and the information you’ve collected.

Now that there’s a counterargument that tries to challenge your position, you can refute it by mentioning the flaws in it.

It’s best to analyze the counterargument carefully. Doing so will make it easy for you to identify the weaknesses, which you can point out and use the strongest points for rebuttal

2. Give New Points that Contradict the Counterclaims

Imagine yourself in a hall full of debaters. On your left side is an audience that agrees with your arguable claim and on your left is a group of listeners who don’t buy into your argument.

Your opponents in the room are not holding back, especially because they’re constantly raising their hands to question your information.

To win them over in such a situation, you have to play smart by recognizing their stance on the issue but then explaining why they’re wrong.

Now, take a closer look at the structure of an argument . You’ll notice that it features a section for counterclaims, which means you have to address them if your essay must stand out.

Here, it’s ideal to recognize and agree with the counterargument that the opposing side presents. Then, present a new point of view or facts that contradict the arguments.

Doing so will get the opposing side to consider your stance, even if they don’t agree with you entirely.

3. Twist Facts in Favor of Your Argument

Sometimes the other side of the argument may make more sense than yours does. However, that doesn’t mean you have to concede entirely.

You can agree with the other side of the argument, but then twist facts and provide solid evidence to suit your argument.

This strategy can work for just about any topic, including the most complicated or controversial ones that you have never dealt with before.

4. Making an Emotional Plea

Making an emotional plea isn’t a powerful rebuttal strategy, but it can also be a good option to consider.

It’s important to make sure that the emotional appeal you make outweighs the argument that your opponent brings forth.

Given that it’s often the least effective option in most arguments, making an emotional appeal should be a last resort if all the other options fail.

Final Thoughts

As you can see, counterclaims are important in an argumentative essay and there’s more than one way to give your rebuttal.

Whichever approach you use, make sure you use the strongest facts, stats, evidence, or argument to prove that your position on an issue makes more sense that what your opponents currently hold.

Lastly, if you feel like your essay topic is complicated and you have only a few hours to complete the assignment, you can get in touch with Help for Assessment and we’ll point you in the right direction so you get your essay done right.

You may also like

Can turnitin detect the essays i’ve bought online, how to write a last minute essay: 6 tips for better grades, subscribe to our newsletter now.

- How It Works

- Prices & Discounts

A Student's Guide: Crafting an Effective Rebuttal in Argumentative Essays

Table of contents

Share this article

Achieve Academic Success with Expert Assistance!

Crafted from Scratch for You.

Ensuring Your Work’s Originality.

Transform Your Draft into Excellence.

Perfecting Your Paper’s Grammar, Style, and Format (APA, MLA, etc.).

Calculate the cost of your paper

Get ideas for your essay

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Organizing Your Argument

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

How can I effectively present my argument?

In order for your argument to be persuasive, it must use an organizational structure that the audience perceives as both logical and easy to parse. Three argumentative methods —the Toulmin Method , Classical Method , and Rogerian Method — give guidance for how to organize the points in an argument.

Note that these are only three of the most popular models for organizing an argument. Alternatives exist. Be sure to consult your instructor and/or defer to your assignment’s directions if you’re unsure which to use (if any).

Toulmin Method

The Toulmin Method is a formula that allows writers to build a sturdy logical foundation for their arguments. First proposed by author Stephen Toulmin in The Uses of Argument (1958), the Toulmin Method emphasizes building a thorough support structure for each of an argument's key claims.

The basic format for the Toulmin Method is as follows:

Claim: In this section, you explain your overall thesis on the subject. In other words, you make your main argument.

Data (Grounds): You should use evidence to support the claim. In other words, provide the reader with facts that prove your argument is strong.

Warrant (Bridge): In this section, you explain why or how your data supports the claim. As a result, the underlying assumption that you build your argument on is grounded in reason.

Backing (Foundation): Here, you provide any additional logic or reasoning that may be necessary to support the warrant.

Counterclaim: You should anticipate a counterclaim that negates the main points in your argument. Don't avoid arguments that oppose your own. Instead, become familiar with the opposing perspective. If you respond to counterclaims, you appear unbiased (and, therefore, you earn the respect of your readers). You may even want to include several counterclaims to show that you have thoroughly researched the topic.

Rebuttal: In this section, you incorporate your own evidence that disagrees with the counterclaim. It is essential to include a thorough warrant or bridge to strengthen your essay’s argument. If you present data to your audience without explaining how it supports your thesis, your readers may not make a connection between the two, or they may draw different conclusions.

Example of the Toulmin Method:

Claim: Hybrid cars are an effective strategy to fight pollution.

Data1: Driving a private car is a typical citizen's most air-polluting activity.

Warrant 1: Due to the fact that cars are the largest source of private (as opposed to industrial) air pollution, switching to hybrid cars should have an impact on fighting pollution.

Data 2: Each vehicle produced is going to stay on the road for roughly 12 to 15 years.

Warrant 2: Cars generally have a long lifespan, meaning that the decision to switch to a hybrid car will make a long-term impact on pollution levels.

Data 3: Hybrid cars combine a gasoline engine with a battery-powered electric motor.

Warrant 3: The combination of these technologies produces less pollution.

Counterclaim: Instead of focusing on cars, which still encourages an inefficient culture of driving even as it cuts down on pollution, the nation should focus on building and encouraging the use of mass transit systems.

Rebuttal: While mass transit is an idea that should be encouraged, it is not feasible in many rural and suburban areas, or for people who must commute to work. Thus, hybrid cars are a better solution for much of the nation's population.

Rogerian Method

The Rogerian Method (named for, but not developed by, influential American psychotherapist Carl R. Rogers) is a popular method for controversial issues. This strategy seeks to find a common ground between parties by making the audience understand perspectives that stretch beyond (or even run counter to) the writer’s position. Moreso than other methods, it places an emphasis on reiterating an opponent's argument to his or her satisfaction. The persuasive power of the Rogerian Method lies in its ability to define the terms of the argument in such a way that:

- your position seems like a reasonable compromise.

- you seem compassionate and empathetic.

The basic format of the Rogerian Method is as follows:

Introduction: Introduce the issue to the audience, striving to remain as objective as possible.

Opposing View : Explain the other side’s position in an unbiased way. When you discuss the counterargument without judgement, the opposing side can see how you do not directly dismiss perspectives which conflict with your stance.

Statement of Validity (Understanding): This section discusses how you acknowledge how the other side’s points can be valid under certain circumstances. You identify how and why their perspective makes sense in a specific context, but still present your own argument.

Statement of Your Position: By this point, you have demonstrated that you understand the other side’s viewpoint. In this section, you explain your own stance.

Statement of Contexts : Explore scenarios in which your position has merit. When you explain how your argument is most appropriate for certain contexts, the reader can recognize that you acknowledge the multiple ways to view the complex issue.

Statement of Benefits: You should conclude by explaining to the opposing side why they would benefit from accepting your position. By explaining the advantages of your argument, you close on a positive note without completely dismissing the other side’s perspective.

Example of the Rogerian Method:

Introduction: The issue of whether children should wear school uniforms is subject to some debate.

Opposing View: Some parents think that requiring children to wear uniforms is best.

Statement of Validity (Understanding): Those parents who support uniforms argue that, when all students wear the same uniform, the students can develop a unified sense of school pride and inclusiveness.

Statement of Your Position : Students should not be required to wear school uniforms. Mandatory uniforms would forbid choices that allow students to be creative and express themselves through clothing.

Statement of Contexts: However, even if uniforms might hypothetically promote inclusivity, in most real-life contexts, administrators can use uniform policies to enforce conformity. Students should have the option to explore their identity through clothing without the fear of being ostracized.

Statement of Benefits: Though both sides seek to promote students' best interests, students should not be required to wear school uniforms. By giving students freedom over their choice, students can explore their self-identity by choosing how to present themselves to their peers.

Classical Method

The Classical Method of structuring an argument is another common way to organize your points. Originally devised by the Greek philosopher Aristotle (and then later developed by Roman thinkers like Cicero and Quintilian), classical arguments tend to focus on issues of definition and the careful application of evidence. Thus, the underlying assumption of classical argumentation is that, when all parties understand the issue perfectly, the correct course of action will be clear.

The basic format of the Classical Method is as follows:

Introduction (Exordium): Introduce the issue and explain its significance. You should also establish your credibility and the topic’s legitimacy.

Statement of Background (Narratio): Present vital contextual or historical information to the audience to further their understanding of the issue. By doing so, you provide the reader with a working knowledge about the topic independent of your own stance.

Proposition (Propositio): After you provide the reader with contextual knowledge, you are ready to state your claims which relate to the information you have provided previously. This section outlines your major points for the reader.

Proof (Confirmatio): You should explain your reasons and evidence to the reader. Be sure to thoroughly justify your reasons. In this section, if necessary, you can provide supplementary evidence and subpoints.

Refutation (Refuatio): In this section, you address anticipated counterarguments that disagree with your thesis. Though you acknowledge the other side’s perspective, it is important to prove why your stance is more logical.

Conclusion (Peroratio): You should summarize your main points. The conclusion also caters to the reader’s emotions and values. The use of pathos here makes the reader more inclined to consider your argument.

Example of the Classical Method:

Introduction (Exordium): Millions of workers are paid a set hourly wage nationwide. The federal minimum wage is standardized to protect workers from being paid too little. Research points to many viewpoints on how much to pay these workers. Some families cannot afford to support their households on the current wages provided for performing a minimum wage job .

Statement of Background (Narratio): Currently, millions of American workers struggle to make ends meet on a minimum wage. This puts a strain on workers’ personal and professional lives. Some work multiple jobs to provide for their families.

Proposition (Propositio): The current federal minimum wage should be increased to better accommodate millions of overworked Americans. By raising the minimum wage, workers can spend more time cultivating their livelihoods.

Proof (Confirmatio): According to the United States Department of Labor, 80.4 million Americans work for an hourly wage, but nearly 1.3 million receive wages less than the federal minimum. The pay raise will alleviate the stress of these workers. Their lives would benefit from this raise because it affects multiple areas of their lives.

Refutation (Refuatio): There is some evidence that raising the federal wage might increase the cost of living. However, other evidence contradicts this or suggests that the increase would not be great. Additionally, worries about a cost of living increase must be balanced with the benefits of providing necessary funds to millions of hardworking Americans.

Conclusion (Peroratio): If the federal minimum wage was raised, many workers could alleviate some of their financial burdens. As a result, their emotional wellbeing would improve overall. Though some argue that the cost of living could increase, the benefits outweigh the potential drawbacks.

English Current

ESL Lesson Plans, Tests, & Ideas

- North American Idioms

- Business Idioms

- Idioms Quiz

- Idiom Requests

- Proverbs Quiz & List

- Phrasal Verbs Quiz

- Basic Phrasal Verbs

- North American Idioms App

- A(n)/The: Help Understanding Articles

- The First & Second Conditional

- The Difference between 'So' & 'Too'

- The Difference between 'a few/few/a little/little'

- The Difference between "Other" & "Another"

- Check Your Level

- English Vocabulary

- Verb Tenses (Intermediate)

- Articles (A, An, The) Exercises

- Prepositions Exercises

- Irregular Verb Exercises

- Gerunds & Infinitives Exercises

- Discussion Questions

- Speech Topics

- Argumentative Essay Topics

- Top-rated Lessons

- Intermediate

- Upper-Intermediate

- Reading Lessons

- View Topic List

- Expressions for Everyday Situations

- Travel Agency Activity

- Present Progressive with Mr. Bean

- Work-related Idioms

- Adjectives to Describe Employees

- Writing for Tone, Tact, and Diplomacy

- Speaking Tactfully

- Advice on Monetizing an ESL Website

- Teaching your First Conversation Class

- How to Teach English Conversation

- Teaching Different Levels

- Teaching Grammar in Conversation Class

- Members' Home

- Update Billing Info.

- Cancel Subscription

- North American Proverbs Quiz & List

- North American Idioms Quiz

- Idioms App (Android)

- 'Be used to'" / 'Use to' / 'Get used to'

- Ergative Verbs and the Passive Voice

- Keywords & Verb Tense Exercises

- Irregular Verb List & Exercises

- Non-Progressive (State) Verbs

- Present Perfect vs. Past Simple

- Present Simple vs. Present Progressive

- Past Perfect vs. Past Simple

- Subject Verb Agreement

- The Passive Voice

- Subject & Object Relative Pronouns

- Relative Pronouns Where/When/Whose

- Commas in Adjective Clauses

- A/An and Word Sounds

- 'The' with Names of Places

- Understanding English Articles

- Article Exercises (All Levels)

- Yes/No Questions

- Wh-Questions

- How far vs. How long

- Affect vs. Effect

- A few vs. few / a little vs. little

- Boring vs. Bored

- Compliment vs. Complement

- Die vs. Dead vs. Death

- Expect vs. Suspect

- Experiences vs. Experience

- Go home vs. Go to home

- Had better vs. have to/must

- Have to vs. Have got to

- I.e. vs. E.g.

- In accordance with vs. According to

- Lay vs. Lie

- Make vs. Do

- In the meantime vs. Meanwhile

- Need vs. Require

- Notice vs. Note

- 'Other' vs 'Another'

- Pain vs. Painful vs. In Pain

- Raise vs. Rise

- So vs. Such

- So vs. So that

- Some vs. Some of / Most vs. Most of

- Sometimes vs. Sometime

- Too vs. Either vs. Neither

- Weary vs. Wary

- Who vs. Whom

- While vs. During

- While vs. When

- Wish vs. Hope

- 10 Common Writing Mistakes

- 34 Common English Mistakes

- First & Second Conditionals

- Comparative & Superlative Adjectives

- Determiners: This/That/These/Those

- Check Your English Level

- Grammar Quiz (Advanced)

- Vocabulary Test - Multiple Questions

- Vocabulary Quiz - Choose the Word

- Verb Tense Review (Intermediate)

- Verb Tense Exercises (All Levels)

- Conjunction Exercises

- List of Topics

- Business English

- Games for the ESL Classroom

- Pronunciation

- Teaching Your First Conversation Class

- How to Teach English Conversation Class

Argumentative Essays: The Counter-Argument & Refutation

An argumentative essay presents an argument for or against a topic. For example, if your topic is working from home , then your essay would either argue in favor of working from home (this is the for side) or against working from home.

Like most essays, an argumentative essay begins with an introduction that ends with the writer's position (or stance) in the thesis statement .

Introduction Paragraph

(Background information....)

- Thesis statement : Employers should give their workers the option to work from home in order to improve employee well-being and reduce office costs.

This thesis statement shows that the two points I plan to explain in my body paragraphs are 1) working from home improves well-being, and 2) it allows companies to reduce costs. Each topic will have its own paragraph. Here's an example of a very basic essay outline with these ideas:

- Background information

Body Paragraph 1

- Topic Sentence : Workers who work from home have improved well-being .

- Evidence from academic sources

Body Paragraph 2

- Topic Sentence : Furthermore, companies can reduce their expenses by allowing employees to work at home .

- Summary of key points

- Restatement of thesis statement

Does this look like a strong essay? Not really . There are no academic sources (research) used, and also...

You Need to Also Respond to the Counter-Arguments!

The above essay outline is very basic. The argument it presents can be made much stronger if you consider the counter-argument , and then try to respond (refute) its points.

The counter-argument presents the main points on the other side of the debate. Because we are arguing FOR working from home, this means the counter-argument is AGAINST working from home. The best way to find the counter-argument is by reading research on the topic to learn about the other side of the debate. The counter-argument for this topic might include these points:

- Distractions at home > could make it hard to concentrate

- Dishonest/lazy people > might work less because no one is watching

Next, we have to try to respond to the counter-argument in the refutation (or rebuttal/response) paragraph .

The Refutation/Response Paragraph

The purpose of this paragraph is to address the points of the counter-argument and to explain why they are false, somewhat false, or unimportant. So how can we respond to the above counter-argument? With research !

A study by Bloom (2013) followed workers at a call center in China who tried working from home for nine months. Its key results were as follows:

- The performance of people who worked from home increased by 13%

- These workers took fewer breaks and sick-days

- They also worked more minutes per shift

In other words, this study shows that the counter-argument might be false. (Note: To have an even stronger essay, present data from more than one study.) Now we have a refutation.

Where Do We Put the Counter-Argument and Refutation?

Commonly, these sections can go at the beginning of the essay (after the introduction), or at the end of the essay (before the conclusion). Let's put it at the beginning. Now our essay looks like this:

Counter-argument Paragraph

- Dishonest/lazy people might work less because no one is watching

Refutation/Response Paragraph

- Study: Productivity increased by 14%

- (+ other details)

Body Paragraph 3

- Topic Sentence : In addition, people who work from home have improved well-being .

Body Paragraph 4

The outline is stronger now because it includes the counter-argument and refutation. Note that the essay still needs more details and research to become more convincing.

Working from home may increase productivity.

Extra Advice on Argumentative Essays

It's not a compare and contrast essay.

An argumentative essay focuses on one topic (e.g. cats) and argues for or against it. An argumentative essay should not have two topics (e.g. cats vs dogs). When you compare two ideas, you are writing a compare and contrast essay. An argumentative essay has one topic (cats). If you are FOR cats as pets, a simplistic outline for an argumentative essay could look something like this:

- Thesis: Cats are the best pet.

- are unloving

- cause allergy issues

- This is a benefit > Many working people do not have time for a needy pet

- If you have an allergy, do not buy a cat.

- But for most people (without allergies), cats are great

- Supporting Details

Use Language in Counter-Argument That Shows Its Not Your Position

The counter-argument is not your position. To make this clear, use language such as this in your counter-argument:

- Opponents might argue that cats are unloving.

- People who dislike cats would argue that cats are unloving.

- Critics of cats could argue that cats are unloving.

- It could be argued that cats are unloving.

These underlined phrases make it clear that you are presenting someone else's argument , not your own.

Choose the Side with the Strongest Support

Do not choose your side based on your own personal opinion. Instead, do some research and learn the truth about the topic. After you have read the arguments for and against, choose the side with the strongest support as your position.

Do Not Include Too Many Counter-arguments

Include the main (two or three) points in the counter-argument. If you include too many points, refuting these points becomes quite difficult.

If you have any questions, leave a comment below.

- Matthew Barton / Creator of Englishcurrent.com

Additional Resources :

- Writing a Counter-Argument & Refutation (Richland College)

- Language for Counter-Argument and Refutation Paragraphs (Brown's Student Learning Tools)

EnglishCurrent is happily hosted on Dreamhost . If you found this page helpful, consider a donation to our hosting bill to show your support!

26 comments on “ Argumentative Essays: The Counter-Argument & Refutation ”

Thank you professor. It is really helpful.

Can you also put the counter argument in the third paragraph

It depends on what your instructor wants. Generally, a good argumentative essay needs to have a counter-argument and refutation somewhere. Most teachers will probably let you put them anywhere (e.g. in the start, middle, or end) and be happy as long as they are present. But ask your teacher to be sure.

Thank you for the information Professor

how could I address a counter argument for “plastic bags and its consumption should be banned”?

For what reasons do they say they should be banned? You need to address the reasons themselves and show that these reasons are invalid/weak.

Thank you for this useful article. I understand very well.

Thank you for the useful article, this helps me a lot!

Thank you for this useful article which helps me in my study.

Thank you, professor Mylene 102-04

it was very useful for writing essay

Very useful reference body support to began writing a good essay. Thank you!

Really very helpful. Thanks Regards Mayank

Thank you, professor, it is very helpful to write an essay.

It is really helpful thank you

It was a very helpful set of learning materials. I will follow it and use it in my essay writing. Thank you, professor. Regards Isha

Thanks Professor

This was really helpful as it lays the difference between argumentative essay and compare and contrast essay.. Thanks for the clarification.

This is such a helpful guide in composing an argumentative essay. Thank you, professor.

This was really helpful proof, thankyou!

Thanks this was really helpful to me

This was very helpful for us to generate a good form of essay

thank you so much for this useful information.

Thank you so much, Sir. This helps a lot!

Thank you for the information l have learnt a lot.

Thanks so much .i have the basics information i needed

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

How to Write a Rebuttal Essay

The function of a rebuttal is to disarm an opponent's argument. By addressing and challenging each aspect of a claim, a rebuttal provides a counter-argument, which is itself a type of argument. In the case of a rebuttal essay, the introduction should present a clear thesis statement and the body paragraphs should provide evidence and analysis to disprove the opposing claim.

Understanding the Opposing Argument

A rebuttal essay must show that the writer understands the original argument before attempting to counter it. You must read the original claim carefully, paying close attention to the explanation and examples used to support the point. For example, a claim arguing that schools should enforce mandatory uniforms for its students could support its point by saying that uniforms save money for families and they allow students to focus more intently on their studies.

Advertisement

Article continues below this ad

Formulating a Thesis

Once you are familiar with the opposing argument, you must write a thesis statement -- an overall point for the whole essay. In the case of a rebuttal essay, this single sentence should directly oppose the thesis statement of the original claim which you are countering. The thesis statement should be specific in its wording and content and should be posing a clear argument. For example, if the original thesis statement is "Scientists should not conduct testing on animals because it is inhumane," you can write "The most humane and beneficial way to test medicine for human illnesses is to first test it on animals."

More For You

Important elements in writing argument essays, where is the thesis statement often found in an essay, teaching kids how to write an introductory paragraph, how to write a higher level essay introduction, how to write a college narrative essay.

The body paragraphs of a rebuttal essay should address and counter the opposing argument point-by-point. Northern Illinois University states that a rebuttal can take several approaches when countering an argument, including addressing faulty assumptions, contradictions, unconvincing examples and errors in relating causes to effects. For every argument you present in a body paragraph, you should provide analysis, explanation and specific examples that support your overall point. Countering does not only imply disproving a point entirely, but it can also mean showing that the opposing claim is inferior to your own claim or that it is in some way flawed and therefore not credible.

Writing a Conclusion

The conclusion of your rebuttal essay should synthesize rather than restate the main points of the essay. Use the final paragraph to emphasize the strengths of your argument while also directing the reader's attention to a larger or broader meaning. St. Cloud State University suggests posing questions, looking into the future and challenging the reader in the essay's conclusion. Like a lawyer's closing arguments in a court case, the concluding paragraph is the last thing the reader hears; therefore, you should make this section have a strong impact by being specific and straight to the point.

- Northern Illinois University: An Introduction to Rebuttals

- Purdue University Writing Lab: Rebuttal Sections

- St. Cloud State University: Strategies for Writing a Conclusion

- The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill: Argument

Soheila Battaglia is a published and award-winning author and filmmaker. She holds an MA in literary cultures from New York University and a BA in ethnic studies from UC Berkeley. She is a college professor of literature and composition.

Consider the following thesis for a short paper that analyzes different approaches to stopping climate change:

Climate activism that focuses on personal actions such as recycling obscures the need for systemic change that will be required to slow carbon emissions.

The author of this thesis is promising to make the case that personal actions not only will not solve the climate problem but may actually make the problem more difficult to solve. In order to make a convincing argument, the author will need to consider how thoughtful people might disagree with this claim. In this case, the author might anticipate the following counterarguments:

- By encouraging personal actions, climate activists may raise awareness of the problem and encourage people to support larger systemic change.

- Personal actions on a global level would actually make a difference.

- Personal actions may not make a difference, but they will not obscure the need for systemic solutions.

- Personal actions cannot be put into one category and must be differentiated.

In order to make a convincing argument, the author of this essay may need to address these potential counterarguments. But you don’t need to address every possible counterargument. Rather, you should engage counterarguments when doing so allows you to strengthen your own argument by explaining how it holds up in relation to other arguments.

How to address counterarguments

Once you have considered the potential counterarguments, you will need to figure out how to address them in your essay. In general, to address a counterargument, you’ll need to take the following steps.

- State the counterargument and explain why a reasonable reader could raise that counterargument.

- Counter the counterargument. How you grapple with a counterargument will depend on what you think it means for your argument. You may explain why your argument is still convincing, even in light of this other position. You may point to a flaw in the counterargument. You may concede that the counterargument gets something right but then explain why it does not undermine your argument. You may explain why the counterargument is not relevant. You may refine your own argument in response to the counterargument.

- Consider the language you are using to address the counterargument. Words like but or however signal to the reader that you are refuting the counterargument. Words like nevertheless or still signal to the reader that your argument is not diminished by the counterargument.

Here’s an example of a paragraph in which a counterargument is raised and addressed.

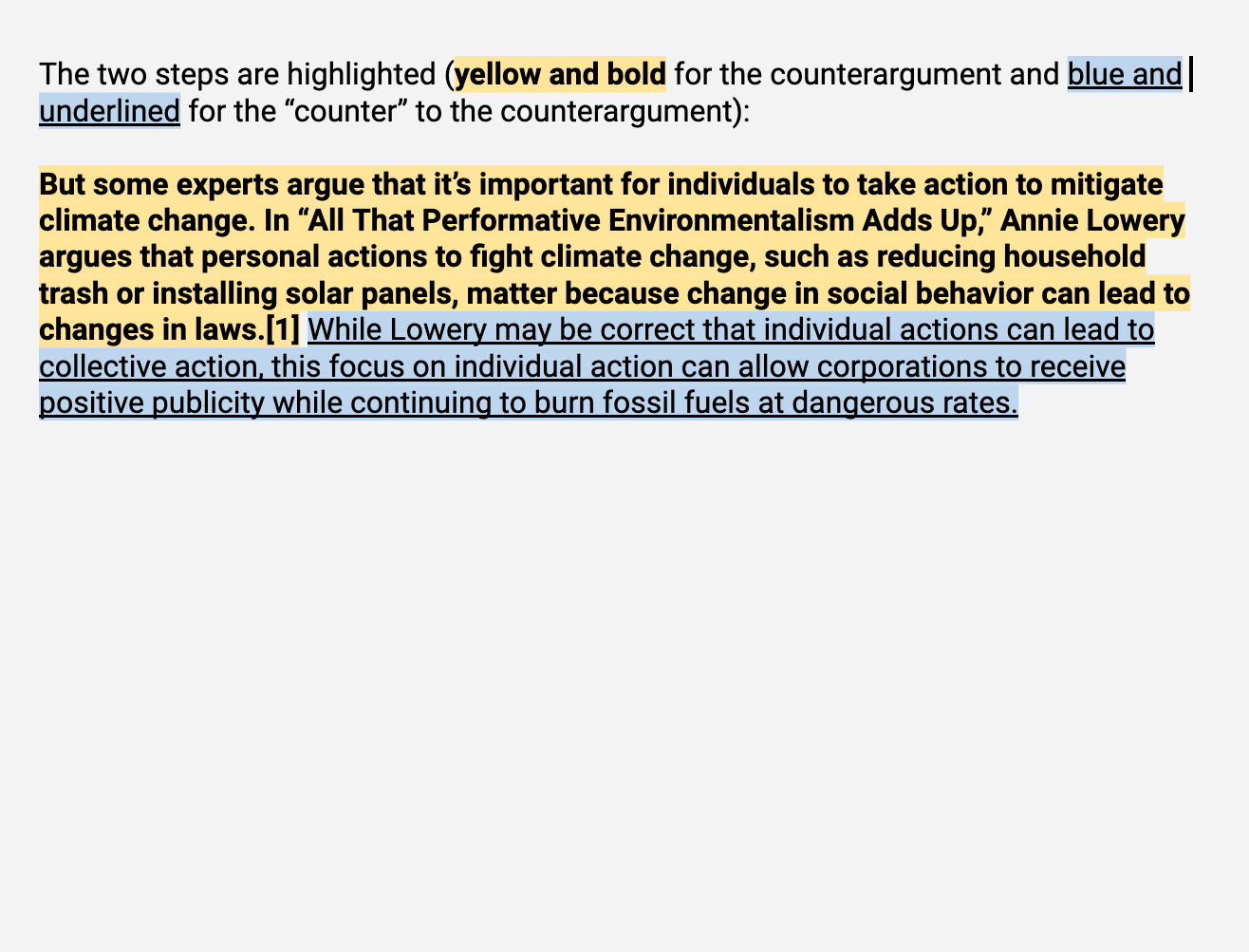

Image version

The two steps are marked with counterargument and “counter” to the counterargument: COUNTERARGUMENT/ But some experts argue that it’s important for individuals to take action to mitigate climate change. In “All That Performative Environmentalism Adds Up,” Annie Lowery argues that personal actions to fight climate change, such as reducing household trash or installing solar panels, matter because change in social behavior can lead to changes in laws. [1]

COUNTER TO THE COUNTERARGUMENT/ While Lowery may be correct that individual actions can lead to collective action, this focus on individual action can allow corporations to receive positive publicity while continuing to burn fossil fuels at dangerous rates.

Where to address counterarguments

There is no one right place for a counterargument—where you raise a particular counterargument will depend on how it fits in with the rest of your argument. The most common spots are the following:

- Before your conclusion This is a common and effective spot for a counterargument because it’s a chance to address anything that you think a reader might still be concerned about after you’ve made your main argument. Don’t put a counterargument in your conclusion, however. At that point, you won’t have the space to address it, and readers may come away confused—or less convinced by your argument.

- Before your thesis Often, your thesis will actually be a counterargument to someone else’s argument. In other words, you will be making your argument because someone else has made an argument that you disagree with. In those cases, you may want to offer that counterargument before you state your thesis to show your readers what’s at stake—someone else has made an unconvincing argument, and you are now going to make a better one.

- After your introduction In some cases, you may want to respond to a counterargument early in your essay, before you get too far into your argument. This is a good option when you think readers may need to understand why the counterargument is not as strong as your argument before you can even launch your own ideas. You might do this in the paragraph right after your thesis.

- Anywhere that makes sense As you draft an essay, you should always keep your readers in mind and think about where a thoughtful reader might disagree with you or raise an objection to an assertion or interpretation of evidence that you are offering. In those spots, you can introduce that potential objection and explain why it does not change your argument. If you think it does affect your argument, you can acknowledge that and explain why your argument is still strong.

[1] Annie Lowery, “All that Performative Environmentalism Adds Up.” The Atlantic . August 31, 2020. https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2020/08/your-tote-bag-can-mak…

- picture_as_pdf Counterargument

Home » Writers-House Blog » A Rebuttal: What It Is and How to Write One

A Rebuttal: What It Is and How to Write One

Students write thousands of essays in their academic career, and they often need to address counterarguments. However, what rebuttals are? Are they the same thing as counterarguments or should students approach them differently? Writers-house.com is here with some helpful tips.

First, a rebuttal isn’t a necessary part of an academic paper. A rebuttal is just a part of an argument. For example, when a student struggles to meet the word count, they can include a rebuttal that will both make the paper longer and strengthen the argument. Let’s consider rebuttals in more details so that everyone can figure out what a rebuttal should look like.

What Is a Rebuttal?

To understand the concept of a rebuttal, students should know how to include it in their argument. Therefore, it makes sense to consider arguments and counterarguments.

- The Argument The first part of the general argument is the author’s point. The author should have a strong opinion on an arguable topic, and the audience should be able to either agree or disagree with it.

- The Counterargument This is the opposing viewpoint. It’s what people who don’t agree with the author would say about the subject matter. The counterargument is also important because it makes the argument stronger, proving that the author has done their research and considered different opinions.

- The Rebuttal The rebuttal connects the argument and the counterargument, explaining why the former is correct and the latter is wrong. When writing a rebuttal, students can acknowledge the opposite opinion why also standing their ground.

For example, when choosing a restaurant, one may come up with an argument that a certain restaurant has great food and a nice atmosphere. A counterargument may state that the atmosphere isn’t good at all because the place is dark and the music is too loud. A possible rebuttal is that the dark atmosphere and loud music are not bad, and everything depends on a particular visitor’s preferences.

A rebuttal is a simple concept. First, the author presents their argument, then they address the counterargument, and then explain why they’re still right. Now let’s consider a rebuttal in an argumentative essay.

An Effective Rebuttal: Writing Strategies

An effective rebuttal shouldn’t just state that an argument is right and the counterargument is wrong. Academic writing requires students to use formal language and to create the right structure

1. Addressing the weaknesses of the counterargument

If a writer acknowledges the counterargument while also addressing its weaknesses, such an approach also helps to strengthen the argument. This way, the writer can demonstrate that they’ve studied the issue and considered different perspectives. Including a rebuttal allows for explaining why the argument is still valid and stronger than the counterargument.

2. Agreeing with the opposite opinion but providing additional information that weakens it

Sometimes, writers might partially agree with a counterargument, because the opposite opinion cannot be always wrong. In this case, the author should provide more information to explain why their point is still stronger, despite the validity of the counterargument. For example, there may be a piece of evidence that weakens the opposite point or illustrates very important exceptions.

Transitions and Their Importance

The argument, counterargument, and rebuttal should be connected so that the paper can be easy to comprehend. Transitions provide such connection, explaining how the author has switched from the argument to the counterargument to avoid possible confusion.

Transitions must help readers identify both the argument and counterargument, briefly explaining how the rebuttal supports the former and disproves or weakens the latter.

Final Thoughts

When writing an academic paper, one shouldn’t forget that both the counterargument and rebuttal should appear at the end of the paper. They must be followed by a strong conclusion that will help readers focus on the author’s point. It’s also important to check the required citation format and to make sure that all the sections of the paper are logically connected.

Leave a Reply

Be the First to Comment!

Place your order

- Essay Writer

- Essay Writing Service

- Term Paper Writing

- Research Paper Writing

- Assignment Writing Service

- Cover Letter Writing

- CV Writing Service

- Resume Writing Service

- 5-Paragraph Essays

- Paper By Subjects

- Affordable Papers

- Prime quality of each and every paper

- Everything written per your instructions

- Native-speaking expert writers

- 100% authenticity guaranteed

- Timely delivery

- Attentive 24/7 customer care team

- Benefits for return customers

- Affordable pricing

25 Counterargument Examples

Chris Drew (PhD)

Dr. Chris Drew is the founder of the Helpful Professor. He holds a PhD in education and has published over 20 articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education. [Image Descriptor: Photo of Chris]

Learn about our Editorial Process

A counterargument is a response, rebuttal, or refutation of an argument with your own argument. Its purpose is to oppose and disprove a theory that someone else has put forward.

We use counterarguments extensively in debates as well as argumentative essay writing.

When teaching essay writing, I teach my students to always present counterarguments to their opponents’ points of view. This helps them to strengthen their own argument and demonstrate awareness of potential rebuttals.

Below are some methods, with examples, that could be used – be it in essay writing, debates, or any other communication genre.

Counterargument Examples

1. empirical challenges.

An empirical challenge is, simply, a rebuttal that challenges the facts presented by the opponent, showing that their facts are wrong and yours are right.

To undermine your opponent’s set of facts, it will be your job to present facts that show that the opponent’s supposed facts are wrong, perhaps due to misreading data or cherry-picking.

Then, you would need to present concrete information, data, or evidence that negates the claim or conclusion of an opponent’s argument.

The core strength of empirical challenges is in their reliance on hard facts and numbers, which are difficult to refute without equally credible opposing data.

Example of Empirical Challenge: If your opponent argues that global warming isn’t a serious issue, an empirical challenge would be to provide scientific data or research studies showing the increase in global temperatures and the harmful effects.

See Also: Empirical Evidence Examples

2. Challenging the Relevance

Challenging the relevance means questioning whether your opponent’s argument or perspective is applicable to the discussion at hand.

This sort of counter-argument seeks to destabilize your opponent’s view by showing that, while their facts or arguments might be sound in isolation, they do not bear any relation to, or are unfit for, the topic at hand, making them irrelevant.

The power of relevance challenge lays in its ability to destabilize your opponent’s argument without needing to directly dispute the truth of their claims.

Example of Challenging the Relevance: You will often find this argument when comparing the usefulness of various research methodologies for a research project. Multiple research methods may be valid, but there’s likely one that’s best for any given study.

See Also: Relevance Examples

3. Reductio ad absurdum

Reductio ad absurdum is a latin term that means reducing to the absurd . This method involves demonstrating the absurdity of an opponent’s argument by showing its illogical or extreme consequences.

The goal is to show that if the argument were valid, it would inevitably lead to senseless or ridiculous outcomes.

The application of reductio ad absurdum is especially effective in debates or discussions where flawed logic or hyperbolic statements are used to influence the audience’s opinion, as it discredits the credibility of the other person’s argument.

Example of Reductio ad absurdum : Consider a scenario where someone argues for the total removal of all regulations on vehicle speed to improve the efficiency of transportation. You can counter this argument through reductio ad absurdum by stating, “By that logic, let’s allow cars to travel at 200 miles per hour down residential streets. After all, it would make the mail delivery much faster!” It becomes evident that permitting extremely high speeds could lead to dangerous conditions and potential for disastrous accidents.

4. Pointing Out Logical Fallacies

The strategy of pointing out logical fallacies involves identifying and highlighting flaws in your opponent’s reasoning.

In a debate or discussion, logical fallacies are often subtle errors that lead to invalid conclusions or arguments.

By identifying these fallacies, you avoid being swayed by flawed reasoning and instead promote cognizant, logical thought.

Successful use of this strategy requires a good understanding of the different kinds of logical fallacies , such as straw man fallacies, ad hominem attacks, and appeals to ignorance.

Example of Pointing Out Logical Fallacies: Consider an argument where your opponent asserts, “All cats I’ve ever seen have been aloof, so all cats must be aloof.” This is a hasty generalization fallacy, where a conclusion about all members of a group is drawn from inadequate sample size.

5. Counterexamples

A counterexample is an example that opposes or contradicts an argument or theory proposed by another.

The use of a counterexample is a practical and powerful means of rebutting an argument or theory that has been presented as absolute or universally applicable.

When you provide a singular example that contradicts your opponent’s proposed theory, it demonstrates the theory isn’t universally true and therefore, weakens their argument.

However, this tactic requires sound knowledge and a good command of subject matter to be able to identify and present valid exceptions.

Example of Counterexamples: Consider an argument where someone states that “Mammals can’t lay eggs.” A solid counterexample would be the platypus, a mammal that does lay eggs. This single example is sufficient to contradict the universal claim.

6. Using Hypotheticals

Hypothetical situations, in essence, are imagined scenarios used to refute your opponent’s point of view. It’s, in essence, an example that is plausible, but not real.

Using hypotheticals assists in clarifying the ramifications of a particular argument, policy, or theory. When a hypothetical scenario effectively illustrates the flaws or shortcomings of your opponent’s viewpoint, it can completely unsettle their position.

However, care must be taken to frame the hypotheticals reasonably and realistically, lest they distort the argument or derail the conversation.

Example of Using Hypotheticals: If someone argues that raising the minimum wage will lead to job loss, you could counter with a hypothetical that if businesses paid their employees more, those employees would have more spending power, bolstering the economy and creating more jobs.

7. Comparison and Contrast

Comparison and contrast entails directly comparing your argument to your opponent’s, showing the strength of your perspective and the weakness of the opponent’s.

This tool allows you to support your arguments or disprove your opponent’s by using existing examples or situations that illustrate your point clearly.

The technique relies heavily on the logical thinking of comparing two or more entities in a manner that is informative, convincing, and significant to the argument.

Example of Comparison and Contrast: Let’s say, for instance, you are arguing against privatization of public utilities. You could compare the rates and services of private utilities to those of public ones showing that private companies often charge more for the same services, thereby supporting your argument against privatization.

See More: Compare and Contrast Examples

8. Challenging Biases

Challenging biases involves questioning the objectivity of your opponent’s argument by pointing out the predispositions that may influence their perspective.

Biases can greatly affect the validity and reliability of an argument because they can skew the interpretation of information and hinder fair judgement.

By challenging biases, you can expose the partiality in your opponent’s argument, thereby diminishing its credibility and persuasiveness.

However, it’s important to respectfully and tactfully challenge biases to prevent the discussion from turning into a personal attack.

Example of Challenging Biases: If your opponent is a staunch supporter of a political party and they provide an argument that solely favors this party, you could challenge their bias by questioning whether their support for the party is unduly influencing their viewpoint, hence the need for them to consider the opposing perspectives.

See More: List of Different Biases

9. Ethical Dispute

Ethical disputes involve challenging your opponent’s argument based on moral values or principles.

Ethics play a crucial role in shaping people’s beliefs, attitudes, and actions. Therefore, ethical disputes can serve as powerful counterarguments, especially in debates concerning sensitive or controversial topics.

If your opponent’s position contradicts generally accepted ethical norms or values, you can point this out to weaken their argument.

Just remember, ethics can occasionally be subjective and personal, so it’s important to approach ethical disputes with sensitivity and respect.

Example of Ethical Dispute: If your opponent supports factory farming based on economic benefits, you could challenge their argument by pointing out the ethical issues related to animal welfare and the environment.

10. Challenging the Source

Challenging the source is a tactic used to question the credibility or reliability of the information used by your opponent in their argument.

This technique focuses on examining the origin of the evidence presented, probing whether the source is credible, trusted, and free from bias.

To do this, I recommend using this media literacy framework .

If the source used by your opponent is flawed, biased or unreliable, their argument loses credibility, making your position stronger.

Example of Challenging the Source: If your opponent uses an obscure blog as their primary source of their argument on a scientific topic, you could challenge the source by questioning its credibility and offering information from reputable scientific journals instead.

See More: Good Sources for Essay Writing

A Full List of Methods for Counterargument

- Empirical challenges

- Challenging the relevance

- Reductio ad absurdum

- Pointing out logical fallacies

- Counterexamples

- Using hypotheticals

- Comparison and contrast

- Challenging biases

- Ethical dispute

- Challenging the source

- Questioning assumptions

- Slippery slope argument

- Challenging a false dichtomy

- Historical Precedent

- Anecdotal Evidence

- Challenging the Definition

- Socratic Questioning

- Highlighting Unintended Consequences

- Appeal to Emotion

- Challenging the Frame

- Highlighting Inconsistencies

- Challenging Completeness

- Temporal Challenge

- Offering alternative explanations

- Exposing oversimplifications

- Appeal to authority

Counterargument is an essential skill for debaters and essay writers. You need to be able to know and understand strategies for countering the arguments of your opponents to position your argument in the best light possible. To do this, we have to vectors of attack: First, you can undermine their arguments and demonstrate the flaws. Second, you can present your argument as stronger.

The key, however, is to ensure your arguments are as airtight and foolproof as possible to prevent effective rebuttals to your own counterarguments!

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 10 Reasons you’re Perpetually Single

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 20 Montessori Toddler Bedrooms (Design Inspiration)

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 21 Montessori Homeschool Setups

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 101 Hidden Talents Examples

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

How to Write a Rebuttal Essay — An Easy Guide to Follow

Ever wondered how to write a rebuttal essay? Face this academic assignment for the first time and can’t find an understandable guide to follow? Don’t worry because here you’ll find a detailed guideline allowing you to set the record straight and understand what tips to follow while writing. We’ll take a look at all the aspects of writing, check what rebuttal in an essay is and list all tips to follow.

What Is a Rebuttal in an Essay — Simple Explanation

Academicians also call this form of writing a counter-argument essay. Its principal mission is to respond to some points made by a person. If you render a decision to answer one or another argument, you should present a rebuttal which is also known as a counter-argument. Otherwise stated, it is a simple attempt to disprove some statements by suggesting a counter-argument.

At a glance, this task seems to be quite challenging. However, rebuttal argument essay writing doesn’t take a massive amount of time. You just need to air your personal opinion on one or another situation.

Related essays:

- Economic recession essay

- Hamlet & formal structure

- The counter revolution and the 1960s essay

- Viacom Strategic Analysis essay

Nevertheless, your viewpoint should be based on your research and comprise a strong thesis statement. An excellent essay can even change the opinion of the intended audience. Thus, you need to be very attentive while writing and use only strong and double-checked arguments.

How to Do a Rebuttal in an Essay — Useful Tutorial

Firstly, you should conduct simple research before you start expressing your ideas. Don’t tend to procrastinate this task because it is tough to organize your thoughts when your deadline is dangerously close. If you don’t have a desire to spend the whole night poring over the books, it is better to start processing the literature as soon as possible. It would be great if you subdivide this task into a few sections. As a result, it will be easier to work!

The majority of academicians have not the slightest idea how to answer the question of how to start a rebuttal in an essay. In sober fact, you need to start with a strong introduction, comprising a thesis statement. Besides, your introductory part should explain what particular situation you are going to discuss. Your core audience should look it through and immediately understand what position you desire to explore.

You should create a list of claims and build your essay structure in the way allowing you to explain each claim one by one. Writing a rebuttal essay, you should follow a pre-written outline. As a result, you won’t face difficulties with the structure.

For instance, there is a particular situation, and you don’t agree with it. You wish to prove the targeted audience that your idea is correct. In this scenario, you need to state your opinion in a thesis statement and list all counter-arguments one by one.

Each rebuttal paragraph should be short and complete. Besides, you should avoid making too general statements because your targeted audience won’t understand what you mean. If you wish to air your proof-point, you should try to make more precise arguments. As a result, your readers won’t face difficulties trying to understand what you mean.

Rebuttal Essay Outline — Why Should You Create It

As well as any other academic paper, this one also should have a plan to follow. Your rebuttal essay outline is a sterling opportunity to organize your thoughts and create an approximate plan to follow. Commonly, your outline should look like this:

- Short but informative introduction with a thesis statement (just a few sentences).

- 3 or 5 body paragraphs presenting all counter-arguments.

- Strong conclusion where you should repeat your opinion once again.

For you not to forget some ideas, we highly recommend writing a list of all claims you wish to discuss in all paragraphs. Even if you are a seasoned writer who is engaged in this area and deals with creative assignments on a rolling basis, you won’t regret it. You’ll spend a few minutes creating the outline, but the general content of your essay will be considerably better.

Top-7 Rebuttal Essay Topics for Students

If you really can’t render a correct decision and pick a worthy topic, look through the rebuttal essay ideas published below. You can’t go wrong if you choose one of the below-listed ideas:

- Is it necessary to sentence juveniles to life imprisonment?

- Why are electro cars better for the environment?

- Distance learning is more effective than the traditional approach to education.

- Why should animal testing be forbidden?

- Modern drones can help police solve the crimes faster.

- Why should smoking marijuana be prohibited?

- Why should the screentime of kids be limited?

We hope our tips will help you catch the inspiration and create a compelling essay which will make your audience think of the discussed problem and even change their minds.

- Character Education

- Classroom Management

- Cultural Responsive

- Differentiation

- Distance Learning

- Explicit Teaching

- Figurative Language

- Interactive Notebooks

- Mentor Text

- Monthly/Seasonal

- Organization

- Social Emotional Learning

- Social Studies

- Step-by-Step Instruction

- Teaching Tips

- Testing and Review

- Freebie Vault Registration

- Login Freebie Album

- Lost Password Freebie Album

- FREE Rockstar Community

- In the News

- Writing Resources

- Reading Resources

- Social Studies Resources

- Interactive Writing Notebooks

- Interactive Reading Notebooks

- Teacher Finds

- Follow Amazon Teacher Finds on Instagram

- Pappy’s Butterfly: A Tale of Perseverance

- Rockstar Writers® Members Portal Login

- FREE MASTERCLASS: Turn Reluctant Writers into Rockstar Writers®

- Enroll in Rockstar Writers®

In an argumentative essay, a rebuttal is a counterargument or response to an opposing viewpoint. It is a crucial part of the essay’s structure because it allows you to address and refute the arguments made by those who disagree with your position or claim. A well-constructed rebuttal strengthens your overall argument by showing that you’ve considered opposing views and can defend your stance effectively.

For example:

Here’s how the structure of a rebuttal typically works in an argumentative essay:

Introduction to the Opposition

Begin by introducing the opposing viewpoint or counterargument. Make it clear what position you are addressing.

Present the Opposition's Argument

Summarize the key points of the opposing argument as fairly and accurately as possible. You should avoid misrepresenting the opposing view.

This is the heart of the rebuttal section. Here, you present your counterarguments to each point made by the opposition. You need to provide evidence, reasoning, or examples that undermine the credibility of the opposing argument. You might also expose any flaws or weaknesses in their reasoning.

Concluding Statement

Summarize your rebuttal by restating your original claim and showing how your counterarguments support your position.

By including a well-structured rebuttal, you demonstrate that you have thoroughly researched the topic and considered different perspectives. This can make your argument more persuasive, showing that you’ve thought critically about the issue and have strong reasons for your position. It also helps you anticipate and address potential objections your readers may have.

Check below for MORE ARGUMENTATIVE ESSAY BLOGPOSTS and WRITING UNITS to guide your instruction!

Keep Rockin’,

SEE SIMILAR BLOGS:

DISCOVER RELATED RESOURCES:

7th Grade Printable Argumentative Writing Unit

8th Grade Argumentative Writing – Printable Version – Middle School – Modeling

8TH GRADE WRITING 8TH GRADE NARRATIVE WRITING ARGUMENTATIVE WRITING INFORMATIVE

Argumentative Writing for Middle School Digital Version

Step-by-Step Argumentative Writing Grades 6-8

STEP-BY-STEP DIGITAL WRITING PROGRAM FOR MIDDLE SCHOOL

WRITING PROGRAM BUNDLE MIDDLE SCHOOL – PRINTABLE AND DIGITAL

Share this post on pinterest:.

WHAT IS A WARRANT IN AN ARGUMENTATIVE ESSAY?

10 teaching activities for women’s history month.

What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

I t started when my brain gave out on me in algebra class one January day in 2022. I couldn’t figure out a simple math problem; all I saw were numbers and symbols. My eyelids drooped, my head hurt, I could barely stay awake. Something wasn’t right.