18 Qualitative Research Examples

Chris Drew (PhD)

Dr. Chris Drew is the founder of the Helpful Professor. He holds a PhD in education and has published over 20 articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education. [Image Descriptor: Photo of Chris]

Learn about our Editorial Process

Qualitative research is an approach to scientific research that involves using observation to gather and analyze non-numerical, in-depth, and well-contextualized datasets.

It serves as an integral part of academic, professional, and even daily decision-making processes (Baxter & Jack, 2008).

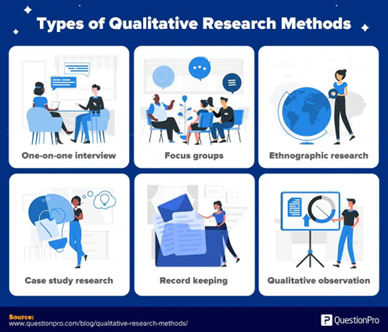

Methods of qualitative research encompass a wide range of techniques, from in-depth personal encounters, like ethnographies (studying cultures in-depth) and autoethnographies (examining one’s own cultural experiences), to collection of diverse perspectives on topics through methods like interviewing focus groups (gatherings of individuals to discuss specific topics).

Qualitative Research Examples

1. ethnography.

Definition: Ethnography is a qualitative research design aimed at exploring cultural phenomena. Rooted in the discipline of anthropology , this research approach investigates the social interactions, behaviors, and perceptions within groups, communities, or organizations.

Ethnographic research is characterized by extended observation of the group, often through direct participation, in the participants’ environment. An ethnographer typically lives with the study group for extended periods, intricately observing their everyday lives (Khan, 2014).

It aims to present a complete, detailed and accurate picture of the observed social life, rituals, symbols, and values from the perspective of the study group.

Example of Ethnographic Research

Title: “ The Everyday Lives of Men: An Ethnographic Investigation of Young Adult Male Identity “

Citation: Evans, J. (2010). The Everyday Lives of Men: An Ethnographic Investigation of Young Adult Male Identity. Peter Lang.

Overview: This study by Evans (2010) provides a rich narrative of young adult male identity as experienced in everyday life. The author immersed himself among a group of young men, participating in their activities and cultivating a deep understanding of their lifestyle, values, and motivations. This research exemplified the ethnographic approach, revealing complexities of the subjects’ identities and societal roles, which could hardly be accessed through other qualitative research designs.

Read my Full Guide on Ethnography Here

2. Autoethnography

Definition: Autoethnography is an approach to qualitative research where the researcher uses their own personal experiences to extend the understanding of a certain group, culture, or setting. Essentially, it allows for the exploration of self within the context of social phenomena.

Unlike traditional ethnography, which focuses on the study of others, autoethnography turns the ethnographic gaze inward, allowing the researcher to use their personal experiences within a culture as rich qualitative data (Durham, 2019).

The objective is to critically appraise one’s personal experiences as they navigate and negotiate cultural, political, and social meanings. The researcher becomes both the observer and the participant, intertwining personal and cultural experiences in the research.

Example of Autoethnographic Research

Title: “ A Day In The Life Of An NHS Nurse “

Citation: Osben, J. (2019). A day in the life of a NHS nurse in 21st Century Britain: An auto-ethnography. The Journal of Autoethnography for Health & Social Care. 1(1).

Overview: This study presents an autoethnography of a day in the life of an NHS nurse (who, of course, is also the researcher). The author uses the research to achieve reflexivity, with the researcher concluding: “Scrutinising my practice and situating it within a wider contextual backdrop has compelled me to significantly increase my level of scrutiny into the driving forces that influence my practice.”

Read my Full Guide on Autoethnography Here

3. Semi-Structured Interviews

Definition: Semi-structured interviews stand as one of the most frequently used methods in qualitative research. These interviews are planned and utilize a set of pre-established questions, but also allow for the interviewer to steer the conversation in other directions based on the responses given by the interviewee.

In semi-structured interviews, the interviewer prepares a guide that outlines the focal points of the discussion. However, the interview is flexible, allowing for more in-depth probing if the interviewer deems it necessary (Qu, & Dumay, 2011). This style of interviewing strikes a balance between structured ones which might limit the discussion, and unstructured ones, which could lack focus.

Example of Semi-Structured Interview Research

Title: “ Factors influencing adherence to cancer treatment in older adults with cancer: a systematic review “

Citation: Puts, M., et al. (2014). Factors influencing adherence to cancer treatment in older adults with cancer: a systematic review. Annals of oncology, 25 (3), 564-577.

Overview: Puts et al. (2014) executed an extensive systematic review in which they conducted semi-structured interviews with older adults suffering from cancer to examine the factors influencing their adherence to cancer treatment. The findings suggested that various factors, including side effects, faith in healthcare professionals, and social support have substantial impacts on treatment adherence. This research demonstrates how semi-structured interviews can provide rich and profound insights into the subjective experiences of patients.

4. Focus Groups

Definition: Focus groups are a qualitative research method that involves organized discussion with a selected group of individuals to gain their perspectives on a specific concept, product, or phenomenon. Typically, these discussions are guided by a moderator.

During a focus group session, the moderator has a list of questions or topics to discuss, and participants are encouraged to interact with each other (Morgan, 2010). This interactivity can stimulate more information and provide a broader understanding of the issue under scrutiny. The open format allows participants to ask questions and respond freely, offering invaluable insights into attitudes, experiences, and group norms.

Example of Focus Group Research

Title: “ Perspectives of Older Adults on Aging Well: A Focus Group Study “

Citation: Halaweh, H., Dahlin-Ivanoff, S., Svantesson, U., & Willén, C. (2018). Perspectives of older adults on aging well: a focus group study. Journal of aging research .

Overview: This study aimed to explore what older adults (aged 60 years and older) perceived to be ‘aging well’. The researchers identified three major themes from their focus group interviews: a sense of well-being, having good physical health, and preserving good mental health. The findings highlight the importance of factors such as positive emotions, social engagement, physical activity, healthy eating habits, and maintaining independence in promoting aging well among older adults.

5. Phenomenology

Definition: Phenomenology, a qualitative research method, involves the examination of lived experiences to gain an in-depth understanding of the essence or underlying meanings of a phenomenon.

The focus of phenomenology lies in meticulously describing participants’ conscious experiences related to the chosen phenomenon (Padilla-Díaz, 2015).

In a phenomenological study, the researcher collects detailed, first-hand perspectives of the participants, typically via in-depth interviews, and then uses various strategies to interpret and structure these experiences, ultimately revealing essential themes (Creswell, 2013). This approach focuses on the perspective of individuals experiencing the phenomenon, seeking to explore, clarify, and understand the meanings they attach to those experiences.

Example of Phenomenology Research

Title: “ A phenomenological approach to experiences with technology: current state, promise, and future directions for research ”

Citation: Cilesiz, S. (2011). A phenomenological approach to experiences with technology: Current state, promise, and future directions for research. Educational Technology Research and Development, 59 , 487-510.

Overview: A phenomenological approach to experiences with technology by Sebnem Cilesiz represents a good starting point for formulating a phenomenological study. With its focus on the ‘essence of experience’, this piece presents methodological, reliability, validity, and data analysis techniques that phenomenologists use to explain how people experience technology in their everyday lives.

6. Grounded Theory

Definition: Grounded theory is a systematic methodology in qualitative research that typically applies inductive reasoning . The primary aim is to develop a theoretical explanation or framework for a process, action, or interaction grounded in, and arising from, empirical data (Birks & Mills, 2015).

In grounded theory, data collection and analysis work together in a recursive process. The researcher collects data, analyses it, and then collects more data based on the evolving understanding of the research context. This ongoing process continues until a comprehensive theory that represents the data and the associated phenomenon emerges – a point known as theoretical saturation (Charmaz, 2014).

Example of Grounded Theory Research

Title: “ Student Engagement in High School Classrooms from the Perspective of Flow Theory “

Citation: Shernoff, D. J., Csikszentmihalyi, M., Shneider, B., & Shernoff, E. S. (2003). Student engagement in high school classrooms from the perspective of flow theory. School Psychology Quarterly, 18 (2), 158–176.

Overview: Shernoff and colleagues (2003) used grounded theory to explore student engagement in high school classrooms. The researchers collected data through student self-reports, interviews, and observations. Key findings revealed that academic challenge, student autonomy, and teacher support emerged as the most significant factors influencing students’ engagement, demonstrating how grounded theory can illuminate complex dynamics within real-world contexts.

7. Narrative Research

Definition: Narrative research is a qualitative research method dedicated to storytelling and understanding how individuals experience the world. It focuses on studying an individual’s life and experiences as narrated by that individual (Polkinghorne, 2013).

In narrative research, the researcher collects data through methods such as interviews, observations , and document analysis. The emphasis is on the stories told by participants – narratives that reflect their experiences, thoughts, and feelings.

These stories are then interpreted by the researcher, who attempts to understand the meaning the participant attributes to these experiences (Josselson, 2011).

Example of Narrative Research

Title: “Narrative Structures and the Language of the Self”

Citation: McAdams, D. P., Josselson, R., & Lieblich, A. (2006). Identity and story: Creating self in narrative . American Psychological Association.

Overview: In this innovative study, McAdams et al. (2006) employed narrative research to explore how individuals construct their identities through the stories they tell about themselves. By examining personal narratives, the researchers discerned patterns associated with characters, motivations, conflicts, and resolutions, contributing valuable insights about the relationship between narrative and individual identity.

8. Case Study Research

Definition: Case study research is a qualitative research method that involves an in-depth investigation of a single instance or event: a case. These ‘cases’ can range from individuals, groups, or entities to specific projects, programs, or strategies (Creswell, 2013).

The case study method typically uses multiple sources of information for comprehensive contextual analysis. It aims to explore and understand the complexity and uniqueness of a particular case in a real-world context (Merriam & Tisdell, 2015). This investigation could result in a detailed description of the case, a process for its development, or an exploration of a related issue or problem.

Example of Case Study Research

Title: “ Teacher’s Role in Fostering Preschoolers’ Computational Thinking: An Exploratory Case Study “

Citation: Wang, X. C., Choi, Y., Benson, K., Eggleston, C., & Weber, D. (2021). Teacher’s role in fostering preschoolers’ computational thinking: An exploratory case study. Early Education and Development , 32 (1), 26-48.

Overview: This study investigates the role of teachers in promoting computational thinking skills in preschoolers. The study utilized a qualitative case study methodology to examine the computational thinking scaffolding strategies employed by a teacher interacting with three preschoolers in a small group setting. The findings highlight the importance of teachers’ guidance in fostering computational thinking practices such as problem reformulation/decomposition, systematic testing, and debugging.

Read about some Famous Case Studies in Psychology Here

9. Participant Observation

Definition: Participant observation has the researcher immerse themselves in a group or community setting to observe the behavior of its members. It is similar to ethnography, but generally, the researcher isn’t embedded for a long period of time.

The researcher, being a participant, engages in daily activities, interactions, and events as a way of conducting a detailed study of a particular social phenomenon (Kawulich, 2005).

The method involves long-term engagement in the field, maintaining detailed records of observed events, informal interviews, direct participation, and reflexivity. This approach allows for a holistic view of the participants’ lived experiences, behaviours, and interactions within their everyday environment (Dewalt, 2011).

Example of Participant Observation Research

Title: Conflict in the boardroom: a participant observation study of supervisory board dynamics

Citation: Heemskerk, E. M., Heemskerk, K., & Wats, M. M. (2017). Conflict in the boardroom: a participant observation study of supervisory board dynamics. Journal of Management & Governance , 21 , 233-263.

Overview: This study examined how conflicts within corporate boards affect their performance. The researchers used a participant observation method, where they actively engaged with 11 supervisory boards and observed their dynamics. They found that having a shared understanding of the board’s role called a common framework, improved performance by reducing relationship conflicts, encouraging task conflicts, and minimizing conflicts between the board and CEO.

10. Non-Participant Observation

Definition: Non-participant observation is a qualitative research method in which the researcher observes the phenomena of interest without actively participating in the situation, setting, or community being studied.

This method allows the researcher to maintain a position of distance, as they are solely an observer and not a participant in the activities being observed (Kawulich, 2005).

During non-participant observation, the researcher typically records field notes on the actions, interactions, and behaviors observed , focusing on specific aspects of the situation deemed relevant to the research question.

This could include verbal and nonverbal communication , activities, interactions, and environmental contexts (Angrosino, 2007). They could also use video or audio recordings or other methods to collect data.

Example of Non-Participant Observation Research

Title: Mental Health Nurses’ attitudes towards mental illness and recovery-oriented practice in acute inpatient psychiatric units: A non-participant observation study

Citation: Sreeram, A., Cross, W. M., & Townsin, L. (2023). Mental Health Nurses’ attitudes towards mental illness and recovery‐oriented practice in acute inpatient psychiatric units: A non‐participant observation study. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing .

Overview: This study investigated the attitudes of mental health nurses towards mental illness and recovery-oriented practice in acute inpatient psychiatric units. The researchers used a non-participant observation method, meaning they observed the nurses without directly participating in their activities. The findings shed light on the nurses’ perspectives and behaviors, providing valuable insights into their attitudes toward mental health and recovery-focused care in these settings.

11. Content Analysis

Definition: Content Analysis involves scrutinizing textual, visual, or spoken content to categorize and quantify information. The goal is to identify patterns, themes, biases, or other characteristics (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005).

Content Analysis is widely used in various disciplines for a multitude of purposes. Researchers typically use this method to distill large amounts of unstructured data, like interview transcripts, newspaper articles, or social media posts, into manageable and meaningful chunks.

When wielded appropriately, Content Analysis can illuminate the density and frequency of certain themes within a dataset, provide insights into how specific terms or concepts are applied contextually, and offer inferences about the meanings of their content and use (Duriau, Reger, & Pfarrer, 2007).

Example of Content Analysis

Title: Framing European politics: A content analysis of press and television news .

Citation: Semetko, H. A., & Valkenburg, P. M. (2000). Framing European politics: A content analysis of press and television news. Journal of Communication, 50 (2), 93-109.

Overview: This study analyzed press and television news articles about European politics using a method called content analysis. The researchers examined the prevalence of different “frames” in the news, which are ways of presenting information to shape audience perceptions. They found that the most common frames were attribution of responsibility, conflict, economic consequences, human interest, and morality.

Read my Full Guide on Content Analysis Here

12. Discourse Analysis

Definition: Discourse Analysis, a qualitative research method, interprets the meanings, functions, and coherence of certain languages in context.

Discourse analysis is typically understood through social constructionism, critical theory , and poststructuralism and used for understanding how language constructs social concepts (Cheek, 2004).

Discourse Analysis offers great breadth, providing tools to examine spoken or written language, often beyond the level of the sentence. It enables researchers to scrutinize how text and talk articulate social and political interactions and hierarchies.

Insight can be garnered from different conversations, institutional text, and media coverage to understand how topics are addressed or framed within a specific social context (Jorgensen & Phillips, 2002).

Example of Discourse Analysis

Title: The construction of teacher identities in educational policy documents: A critical discourse analysis

Citation: Thomas, S. (2005). The construction of teacher identities in educational policy documents: A critical discourse analysis. Critical Studies in Education, 46 (2), 25-44.

Overview: The author examines how an education policy in one state of Australia positions teacher professionalism and teacher identities. While there are competing discourses about professional identity, the policy framework privileges a narrative that frames the ‘good’ teacher as one that accepts ever-tightening control and regulation over their professional practice.

Read my Full Guide on Discourse Analysis Here

13. Action Research

Definition: Action Research is a qualitative research technique that is employed to bring about change while simultaneously studying the process and results of that change.

This method involves a cyclical process of fact-finding, action, evaluation, and reflection (Greenwood & Levin, 2016).

Typically, Action Research is used in the fields of education, social sciences , and community development. The process isn’t just about resolving an issue but also developing knowledge that can be used in the future to address similar or related problems.

The researcher plays an active role in the research process, which is normally broken down into four steps:

- developing a plan to improve what is currently being done

- implementing the plan

- observing the effects of the plan, and

- reflecting upon these effects (Smith, 2010).

Example of Action Research

Title: Using Digital Sandbox Gaming to Improve Creativity Within Boys’ Writing

Citation: Ellison, M., & Drew, C. (2020). Using digital sandbox gaming to improve creativity within boys’ writing. Journal of Research in Childhood Education , 34 (2), 277-287.

Overview: This was a research study one of my research students completed in his own classroom under my supervision. He implemented a digital game-based approach to literacy teaching with boys and interviewed his students to see if the use of games as stimuli for storytelling helped draw them into the learning experience.

Read my Full Guide on Action Research Here

14. Semiotic Analysis

Definition: Semiotic Analysis is a qualitative method of research that interprets signs and symbols in communication to understand sociocultural phenomena. It stems from semiotics, the study of signs and symbols and their use or interpretation (Chandler, 2017).

In a Semiotic Analysis, signs (anything that represents something else) are interpreted based on their significance and the role they play in representing ideas.

This type of research often involves the examination of images, sounds, and word choice to uncover the embedded sociocultural meanings. For example, an advertisement for a car might be studied to learn more about societal views on masculinity or success (Berger, 2010).

Example of Semiotic Research

Title: Shielding the learned body: a semiotic analysis of school badges in New South Wales, Australia

Citation: Symes, C. (2023). Shielding the learned body: a semiotic analysis of school badges in New South Wales, Australia. Semiotica , 2023 (250), 167-190.

Overview: This study examines school badges in New South Wales, Australia, and explores their significance through a semiotic analysis. The badges, which are part of the school’s visual identity, are seen as symbolic representations that convey meanings. The analysis reveals that these badges often draw on heraldic models, incorporating elements like colors, names, motifs, and mottoes that reflect local culture and history, thus connecting students to their national identity. Additionally, the study highlights how some schools have shifted from traditional badges to modern logos and slogans, reflecting a more business-oriented approach.

15. Qualitative Longitudinal Studies

Definition: Qualitative Longitudinal Studies are a research method that involves repeated observation of the same items over an extended period of time.

Unlike a snapshot perspective, this method aims to piece together individual histories and examine the influences and impacts of change (Neale, 2019).

Qualitative Longitudinal Studies provide an in-depth understanding of change as it happens, including changes in people’s lives, their perceptions, and their behaviors.

For instance, this method could be used to follow a group of students through their schooling years to understand the evolution of their learning behaviors and attitudes towards education (Saldaña, 2003).

Example of Qualitative Longitudinal Research

Title: Patient and caregiver perspectives on managing pain in advanced cancer: a qualitative longitudinal study

Citation: Hackett, J., Godfrey, M., & Bennett, M. I. (2016). Patient and caregiver perspectives on managing pain in advanced cancer: a qualitative longitudinal study. Palliative medicine , 30 (8), 711-719.

Overview: This article examines how patients and their caregivers manage pain in advanced cancer through a qualitative longitudinal study. The researchers interviewed patients and caregivers at two different time points and collected audio diaries to gain insights into their experiences, making this study longitudinal.

Read my Full Guide on Longitudinal Research Here

16. Open-Ended Surveys

Definition: Open-Ended Surveys are a type of qualitative research method where respondents provide answers in their own words. Unlike closed-ended surveys, which limit responses to predefined options, open-ended surveys allow for expansive and unsolicited explanations (Fink, 2013).

Open-ended surveys are commonly used in a range of fields, from market research to social studies. As they don’t force respondents into predefined response categories, these surveys help to draw out rich, detailed data that might uncover new variables or ideas.

For example, an open-ended survey might be used to understand customer opinions about a new product or service (Lavrakas, 2008).

Contrast this to a quantitative closed-ended survey, like a Likert scale, which could theoretically help us to come up with generalizable data but is restricted by the questions on the questionnaire, meaning new and surprising data and insights can’t emerge from the survey results in the same way.

Example of Open-Ended Survey Research

Title: Advantages and disadvantages of technology in relationships: Findings from an open-ended survey

Citation: Hertlein, K. M., & Ancheta, K. (2014). Advantages and disadvantages of technology in relationships: Findings from an open-ended survey. The Qualitative Report , 19 (11), 1-11.

Overview: This article examines the advantages and disadvantages of technology in couple relationships through an open-ended survey method. Researchers analyzed responses from 410 undergraduate students to understand how technology affects relationships. They found that technology can contribute to relationship development, management, and enhancement, but it can also create challenges such as distancing, lack of clarity, and impaired trust.

17. Naturalistic Observation

Definition: Naturalistic Observation is a type of qualitative research method that involves observing individuals in their natural environments without interference or manipulation by the researcher.

Naturalistic observation is often used when conducting research on behaviors that cannot be controlled or manipulated in a laboratory setting (Kawulich, 2005).

It is frequently used in the fields of psychology, sociology, and anthropology. For instance, to understand the social dynamics in a schoolyard, a researcher could spend time observing the children interact during their recess, noting their behaviors, interactions, and conflicts without imposing their presence on the children’s activities (Forsyth, 2010).

Example of Naturalistic Observation Research

Title: Dispositional mindfulness in daily life: A naturalistic observation study

Citation: Kaplan, D. M., Raison, C. L., Milek, A., Tackman, A. M., Pace, T. W., & Mehl, M. R. (2018). Dispositional mindfulness in daily life: A naturalistic observation study. PloS one , 13 (11), e0206029.

Overview: In this study, researchers conducted two studies: one exploring assumptions about mindfulness and behavior, and the other using naturalistic observation to examine actual behavioral manifestations of mindfulness. They found that trait mindfulness is associated with a heightened perceptual focus in conversations, suggesting that being mindful is expressed primarily through sharpened attention rather than observable behavioral or social differences.

Read my Full Guide on Naturalistic Observation Here

18. Photo-Elicitation

Definition: Photo-elicitation utilizes photographs as a means to trigger discussions and evoke responses during interviews. This strategy aids in bringing out topics of discussion that may not emerge through verbal prompting alone (Harper, 2002).

Traditionally, Photo-Elicitation has been useful in various fields such as education, psychology, and sociology. The method involves the researcher or participants taking photographs, which are then used as prompts for discussion.

For instance, a researcher studying urban environmental issues might invite participants to photograph areas in their neighborhood that they perceive as environmentally detrimental, and then discuss each photo in depth (Clark-Ibáñez, 2004).

Example of Photo-Elicitation Research

Title: Early adolescent food routines: A photo-elicitation study

Citation: Green, E. M., Spivak, C., & Dollahite, J. S. (2021). Early adolescent food routines: A photo-elicitation study. Appetite, 158 .

Overview: This study focused on early adolescents (ages 10-14) and their food routines. Researchers conducted in-depth interviews using a photo-elicitation approach, where participants took photos related to their food choices and experiences. Through analysis, the study identified various routines and three main themes: family, settings, and meals/foods consumed, revealing how early adolescents view and are influenced by their eating routines.

Features of Qualitative Research

Qualitative research is a research method focused on understanding the meaning individuals or groups attribute to a social or human problem (Creswell, 2013).

Some key features of this method include:

- Naturalistic Inquiry: Qualitative research happens in the natural setting of the phenomena, aiming to understand “real world” situations (Patton, 2015). This immersion in the field or subject allows the researcher to gather a deep understanding of the subject matter.

- Emphasis on Process: It aims to understand how events unfold over time rather than focusing solely on outcomes (Merriam & Tisdell, 2015). The process-oriented nature of qualitative research allows researchers to investigate sequences, timing, and changes.

- Interpretive: It involves interpreting and making sense of phenomena in terms of the meanings people assign to them (Denzin & Lincoln, 2011). This interpretive element allows for rich, nuanced insights into human behavior and experiences.

- Holistic Perspective: Qualitative research seeks to understand the whole phenomenon rather than focusing on individual components (Creswell, 2013). It emphasizes the complex interplay of factors, providing a richer, more nuanced view of the research subject.

- Prioritizes Depth over Breadth: Qualitative research favors depth of understanding over breadth, typically involving a smaller but more focused sample size (Hennink, Hutter, & Bailey, 2020). This enables detailed exploration of the phenomena of interest, often leading to rich and complex data.

Qualitative vs Quantitative Research

Qualitative research centers on exploring and understanding the meaning individuals or groups attribute to a social or human problem (Creswell, 2013).

It involves an in-depth approach to the subject matter, aiming to capture the richness and complexity of human experience.

Examples include conducting interviews, observing behaviors, or analyzing text and images.

There are strengths inherent in this approach. In its focus on understanding subjective experiences and interpretations, qualitative research can yield rich and detailed data that quantitative research may overlook (Denzin & Lincoln, 2011).

Additionally, qualitative research is adaptive, allowing the researcher to respond to new directions and insights as they emerge during the research process.

However, there are also limitations. Because of the interpretive nature of this research, findings may not be generalizable to a broader population (Marshall & Rossman, 2014). Well-designed quantitative research, on the other hand, can be generalizable.

Moreover, the reliability and validity of qualitative data can be challenging to establish due to its subjective nature, unlike quantitative research, which is ideally more objective.

Compare Qualitative and Quantitative Research Methodologies in This Guide Here

In conclusion, qualitative research methods provide distinctive ways to explore social phenomena and understand nuances that quantitative approaches might overlook. Each method, from Ethnography to Photo-Elicitation, presents its strengths and weaknesses but they all offer valuable means of investigating complex, real-world situations. The goal for the researcher is not to find a definitive tool, but to employ the method best suited for their research questions and the context at hand (Almalki, 2016). Above all, these methods underscore the richness of human experience and deepen our understanding of the world around us.

Angrosino, M. (2007). Doing ethnographic and observational research. Sage Publications.

Areni, C. S., & Kim, D. (1994). The influence of in-store lighting on consumers’ examination of merchandise in a wine store. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 11 (2), 117-125.

Barker, C., Pistrang, N., & Elliott, R. (2016). Research Methods in Clinical Psychology: An Introduction for Students and Practitioners. John Wiley & Sons.

Baxter, P. & Jack, S. (2008). Qualitative case study methodology: Study design and implementation for novice researchers. The Qualitative Report, 13 (4), 544-559.

Berger, A. A. (2010). The Objects of Affection: Semiotics and Consumer Culture. Palgrave Macmillan.

Bevan, M. T. (2014). A method of phenomenological interviewing. Qualitative health research, 24 (1), 136-144.

Birks, M., & Mills, J. (2015). Grounded theory: A practical guide . Sage Publications.

Bryman, A. (2015) . The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research. Sage Publications.

Chandler, D. (2017). Semiotics: The Basics. Routledge.

Charmaz, K. (2014). Constructing grounded theory. Sage Publications.

Cheek, J. (2004). At the margins? Discourse analysis and qualitative research. Qualitative Health Research, 14(8), 1140-1150.

Clark-Ibáñez, M. (2004). Framing the social world with photo-elicitation interviews. American Behavioral Scientist, 47(12), 1507-1527.

Creswell, J. W. (2013). Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative and Mixed Methods Approaches. Sage Publications.

Creswell, J. W., & Creswell, J. D. (2017). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. Sage publications.

Crowe, S., Cresswell, K., Robertson, A., Huby, G., Avery, A., & Sheikh, A. (2011). The case study approach. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 11(100), 1-9.

Denzin, N. K., & Lincoln, Y. S. (2011). The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research. Sage.

Dewalt, K. M., & Dewalt, B. R. (2011). Participant observation: A guide for fieldworkers. Rowman Altamira.

Doody, O., Slevin, E., & Taggart, L. (2013). Focus group interviews in nursing research: part 1. British Journal of Nursing, 22(1), 16-19.

Durham, A. (2019). Autoethnography. In P. Atkinson (Ed.), Qualitative Research Methods. Oxford University Press.

Duriau, V. J., Reger, R. K., & Pfarrer, M. D. (2007). A content analysis of the content analysis literature in organization studies: Research themes, data sources, and methodological refinements. Organizational Research Methods, 10(1), 5-34.

Evans, J. (2010). The Everyday Lives of Men: An Ethnographic Investigation of Young Adult Male Identity. Peter Lang.

Farrall, S. (2006). What is qualitative longitudinal research? Papers in Social Research Methods, Qualitative Series, No.11, London School of Economics, Methodology Institute.

Fielding, J., & Fielding, N. (2008). Synergy and synthesis: integrating qualitative and quantitative data. The SAGE handbook of social research methods, 555-571.

Fink, A. (2013). How to conduct surveys: A step-by-step guide . SAGE.

Forsyth, D. R. (2010). Group Dynamics . Wadsworth Cengage Learning.

Fugard, A. J. B., & Potts, H. W. W. (2015). Supporting thinking on sample sizes for thematic analyses: A quantitative tool. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 18 (6), 669–684.

Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Aldine de Gruyter.

Gray, J. R., Grove, S. K., & Sutherland, S. (2017). Burns and Grove’s the Practice of Nursing Research E-Book: Appraisal, Synthesis, and Generation of Evidence. Elsevier Health Sciences.

Greenwood, D. J., & Levin, M. (2016). Introduction to action research: Social research for social change. SAGE.

Harper, D. (2002). Talking about pictures: A case for photo elicitation. Visual Studies, 17 (1), 13-26.

Heinonen, T. (2012). Making Sense of the Social: Human Sciences and the Narrative Turn. Rozenberg Publishers.

Heisley, D. D., & Levy, S. J. (1991). Autodriving: A photoelicitation technique. Journal of Consumer Research, 18 (3), 257-272.

Hennink, M. M., Hutter, I., & Bailey, A. (2020). Qualitative Research Methods . SAGE Publications Ltd.

Hsieh, H. F., & Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three Approaches to Qualitative Content Analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15 (9), 1277–1288.

Jorgensen, D. L. (2015). Participant Observation. In Emerging Trends in the Social and Behavioral Sciences: An Interdisciplinary, Searchable, and Linkable Resource. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Jorgensen, M., & Phillips, L. (2002). Discourse Analysis as Theory and Method . SAGE.

Josselson, R. (2011). Narrative research: Constructing, deconstructing, and reconstructing story. In Five ways of doing qualitative analysis . Guilford Press.

Kawulich, B. B. (2005). Participant observation as a data collection method. Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 6 (2).

Khan, S. (2014). Qualitative Research Method: Grounded Theory. Journal of Basic and Clinical Pharmacy, 5 (4), 86-88.

Koshy, E., Koshy, V., & Waterman, H. (2010). Action Research in Healthcare . SAGE.

Krippendorff, K. (2013). Content Analysis: An Introduction to its Methodology. SAGE.

Lannon, J., & Cooper, P. (2012). Humanistic Advertising: A Holistic Cultural Perspective. International Journal of Advertising, 15 (2), 97–111.

Lavrakas, P. J. (2008). Encyclopedia of survey research methods. SAGE Publications.

Lieblich, A., Tuval-Mashiach, R., & Zilber, T. (2008). Narrative research: Reading, analysis and interpretation. Sage Publications.

Mackey, A., & Gass, S. M. (2015). Second language research: Methodology and design. Routledge.

Marshall, C., & Rossman, G. B. (2014). Designing qualitative research. Sage publications.

McAdams, D. P., Josselson, R., & Lieblich, A. (2006). Identity and story: Creating self in narrative. American Psychological Association.

Merriam, S. B., & Tisdell, E. J. (2015). Qualitative Research: A Guide to Design and Implementation. Jossey-Bass.

Mick, D. G. (1986). Consumer Research and Semiotics: Exploring the Morphology of Signs, Symbols, and Significance. Journal of Consumer Research, 13 (2), 196-213.

Morgan, D. L. (2010). Focus groups as qualitative research. Sage Publications.

Mulhall, A. (2003). In the field: notes on observation in qualitative research. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 41 (3), 306-313.

Neale, B. (2019). What is Qualitative Longitudinal Research? Bloomsbury Publishing.

Nolan, L. B., & Renderos, T. B. (2012). A focus group study on the influence of fatalism and religiosity on cancer risk perceptions in rural, eastern North Carolina. Journal of religion and health, 51 (1), 91-104.

Padilla-Díaz, M. (2015). Phenomenology in educational qualitative research: Philosophy as science or philosophical science? International Journal of Educational Excellence, 1 (2), 101-110.

Parker, I. (2014). Discourse dynamics: Critical analysis for social and individual psychology . Routledge.

Patton, M. Q. (2015). Qualitative research & evaluation methods: Integrating theory and practice . Sage Publications.

Polkinghorne, D. E. (2013). Narrative configuration in qualitative analysis. In Life history and narrative. Routledge.

Puts, M. T., Tapscott, B., Fitch, M., Howell, D., Monette, J., Wan-Chow-Wah, D., Krzyzanowska, M., Leighl, N. B., Springall, E., & Alibhai, S. (2014). Factors influencing adherence to cancer treatment in older adults with cancer: a systematic review. Annals of oncology, 25 (3), 564-577.

Qu, S. Q., & Dumay, J. (2011). The qualitative research interview . Qualitative research in accounting & management.

Ali, J., & Bhaskar, S. B. (2016). Basic statistical tools in research and data analysis. Indian Journal of Anaesthesia, 60 (9), 662–669.

Rosenbaum, M. S. (2017). Exploring the social supportive role of third places in consumers’ lives. Journal of Service Research, 20 (1), 26-42.

Saldaña, J. (2003). Longitudinal Qualitative Research: Analyzing Change Through Time . AltaMira Press.

Saldaña, J. (2014). The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers. SAGE.

Shernoff, D. J., Csikszentmihalyi, M., Shneider, B., & Shernoff, E. S. (2003). Student engagement in high school classrooms from the perspective of flow theory. School Psychology Quarterly, 18 (2), 158-176.

Smith, J. A. (2015). Qualitative Psychology: A Practical Guide to Research Methods . Sage Publications.

Smith, M. K. (2010). Action Research. The encyclopedia of informal education.

Sue, V. M., & Ritter, L. A. (2012). Conducting online surveys . SAGE Publications.

Van Auken, P. M., Frisvoll, S. J., & Stewart, S. I. (2010). Visualising community: using participant-driven photo-elicitation for research and application. Local Environment, 15 (4), 373-388.

Van Voorhis, F. L., & Morgan, B. L. (2007). Understanding Power and Rules of Thumb for Determining Sample Sizes. Tutorials in Quantitative Methods for Psychology, 3 (2), 43–50.

Wodak, R., & Meyer, M. (2015). Methods of Critical Discourse Analysis . SAGE.

Zuber-Skerritt, O. (2018). Action research for developing educational theories and practices . Routledge.

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 10 Reasons you’re Perpetually Single

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 20 Montessori Toddler Bedrooms (Design Inspiration)

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 21 Montessori Homeschool Setups

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 101 Hidden Talents Examples

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Navigating the qualitative manuscript writing process: some tips for authors and reviewers

Chris roberts, koshila kumar, gabrielle finn.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Corresponding author.

Collection date 2020.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Qualitative research explores the ‘black box’ of how phenomena are constituted. Such research can provide rich and diverse insights about social practices and individual experiences across the continuum of undergraduate, postgraduate and continuing education, sectors and contexts. Qualitative research can yield unique data that can complement the numbers generated in quantitative research, [ 1 ] by answering “how” and “why” research questions. As you will notice in this paper, qualitative research is underpinned by specific philosophical assumptions, quality criteria and has a lexicon or a language specific to it.

A simple search of BMC Medical Education suggests that there are over 800 papers that employ qualitative methods either on their own or as part of a mixed methods study to evaluate various phenomena. This represents a considerable investment in time and effort for both researchers and reviewers. This paper is aimed at maximising this investment by helping early career researchers (ECRs) and reviewers new to the qualitative research field become familiar with quality criteria in qualitative research and how these can be applied in the qualitative manuscript writing process. Fortunately, there are numerous guidelines for both authors and for reviewers of qualitative research, including practical “how to” checklists [ 2 , 3 ]. These checklists can be valuable tools to confirm the essential elements of a qualitative study for early career researchers (ECRs). Our advice in this article is not intended to replace such “how to” guidance. Rather, the suggestions we make are intended to help ECRs increase their likelihood of getting published and reviewers to make informed decisions about the quality of qualitative research being submitted for publication in BMC Medical Education. Our advice is themed around long-established criteria for the quality of qualitative research developed by Lincoln and Guba [ 4 ]. (see Table 1 ) Each quality criterion outlined in Table 1 is further expanded in Table 2 in the form of several practical steps pertinent to the process of writing up qualitative research.

Five key criteria for the quality of qualitative research (adapted from Lincoln and Guba, 1995)

Practical steps in preparing qualitative research manuscripts

As a general starting point, the early career writer is advised to consult previously published qualitative papers in the journal to identify the genre (style) and relative emphasis of different components of the research paper. Patton [ 5 ] advises researchers to “FOCUS! FOCUS! FOCUS!” in deciding which components to include in the paper, highlighting the need to exclude side topics that add little to the narrative and reduce the cognitive load for readers and reviewers alike. Authors are also advised to do significant re-writing, rephrasing, re-ordering of initial drafts, to remove faulty grammar, and addresses stylistic and structural problems [ 6 ]. They should be mindful of “the golden thread,” that is their central argument that holds together the literature review, the theoretical and conceptual framework, the research questions, methodology, the analysis and organisation of the data and the conclusions. Getting a draft reviewed by someone outside of the research/writing team is one practical strategy to ensure the manuscript is well presented and relates to the plausibility element.

The introduction of a qualitative paper can be seen as beginning a conversation. Lingard advises that in this conversation, authors need to persuade the reader and reviewer of the strength, originality and contributions of their work [ 7 ]. In constructing a persuasive rationale, ECRs need to clearly distinguish between the qualitative research phenomenon (i.e. the broad research issue or concept under investigation) and the research context (i.e. the local setting or situation) [ 5 ]. The introduction section needs to culminate in a qualitative research question/s. It is important that ECRs are aware that qualitative research questions need to be fine-tuned from their original state to reflect gaps in the literature review, the researcher/s’ philosophical stance, the theory used, or unexpected findings [ 8 ]. This links to the elements of plausibility and consistency outlined in Table 1 .

Also, in the introduction of a qualitative paper, ECRs need to explain the multiple “lenses” through which they have considered complex social phenomena; including the underpinning research paradigm and theory. A research paradigm reveals the researcher/s’ values and assumptions about research and relates to axiology (what do you value?), ontology (what is out there to know?) epistemology (what and how can you know it?), and methodology (how do you go about acquiring that knowledge?) [ 9 ] ECRs are advised to explicitly state their research paradigm and its underpinning assumptions. For example, Ommering et al., state “We established our research within an interpretivist paradigm, emphasizing the subjective nature in understanding human experiences and creation of reality.” [ 10 ] Theory refers to a set of concepts or a conceptual framework that helps the writer to move beyond description to ‘explaining, predicting, or prescribing responses, events, situations, conditions, or relationships.’ [ 11 ] Theory can provide comprehensive understandings at multiple levels, including: the macro or grand level of how societies work, the mid-range level of how organisations operate; and the micro level of how people interact [ 12 ]. Qualitative studies can involve theory application or theory development [ 5 ]. ECRs are advised to briefly summarise their theoretical lens and identify what it means to consider the research phenomenon, process, or concept being studied with that specific lens. For example, Kumar and Greenhill explain how the lens of workplace affordances enabled their paper to draw “attention to the contextual, personal and interactional factors that impact on how clinical educators integrate their educational knowledge and skills into the practice setting, and undertake their educational role.” [ 13 ] Ensuring that the elements of theory and research paradigm are explicit and aligned, enhances plausibility, consistency and transparency of qualitative research. The use of theory can also add to the currency of research by enabling a new lens to be cast on a research phenomenon, process, or concept and reveal something previously unknown or surprising.

Moving to the methods, methodology is a general approach to studying a research topic and establishes how one will go about studying any phenomenon. In contrast, methods are specific research techniques and in qualitative research, data collection methods might include observation or interviewing, or photo elicitation methods, while data analysis methods may include content analysis, narrative analysis, or discourse analysis to mention a few [ 8 ]. ECRs will need to ensure the philosophical assumptions, methodology and methods follow from the introduction of a manuscript and the research question/s, [ 3 ] and this enhances the consistency and transparency elements. Moreover, triangulation or the combining of multiple observers, theories, methods, and data sources, is vital to overcome the limitation of singular methods, lone analysts, and single-perspective theories or models [ 8 ]. ECRs should report on not only what was triangulated but also how it was performed, thereby enhancing the elements of plausibility and consistency. For example, Touchie et al., describe using three researchers, three different focus groups, and representation of three different participant cohorts to ensure triangulation [ 14 ]. When it comes to the analysis of qualitative data, ECRs may claim they have used a specific methodological approach (e.g. interpretative phenomenological approach or a grounded theory approach) whereas the analytical steps are more congruent with a more generalist approach, such as thematic analysis [ 15 ]. ECRs are advised that such methodological approaches are founded on a number of philosophical considerations which need to inform the framing and conduct of a study, not just the analysis process. Alignment between the methodology and the methods informs the consistency, transparency and plausibility elements.

Comprehensively describing the research context in a way that is understandable to an international audience helps to illuminate the specific ‘laboratory’ for the research, and how the processes applied or insights generated in this ‘laboratory’ can be adapted or translated to other contexts. This addresses the relevancy element. To further enhance plausibility and relevance, ECRs should situate their work clearly on the evaluation–research continuum. Although not a strictly qualitative research consideration, evaluation focuses mostly on understanding how specific local practices may have resulted in specific outcomes for learners. While evaluation is vital for quality assurance and improvement, research has a broader and strategic focus and rates more highly against the currency and relevancy criteria. ECRs are more likely to undertake evaluation studies aimed at demonstrating the impact and outcomes of an educational intervention in their local setting, consistent with level one of Kirkpatrick’s criteria [ 16 ]. For example, Palmer and colleagues explain that they aimed to “develop and evaluate a continuing medical education (CME) course aimed at improving healthcare provider knowledge” [ 17 ]. To be competitive for publication, evaluation studies need to (measure and) report on at least level two and above of Kirkpatrick’s criteria. Learning how to problematise and frame the investigation of a problem arising from practice as research, provides ECRs with an opportunity to adopt a more critical and scholarly stance.

Also, in the methods, ECRs may provide detail about the study context and participants but little in the way of personal reflexive statements. Unlike quantitative research which claims that knowledge is objective and seeks to remove subjective influences, qualitative research recognises that subjectivity is inherent and that the researcher is directly involved in interpreting and constructing meanings [ 8 ]. For example, Bindels and colleagues provide a clear and concise description about their own backgrounds making their ‘lens’ explicit and enabling the reader to understand the multiple perspectives that have informed their research process [ 18 ]. Therefore, a clear description of the researcher/s position and relationship to the research phenomenon, context and participants, is vital for transparency, relevance and plausibility. We three are all experienced qualitative researchers, writers, reviewers and are associate editors for BMC Medical Education. We are situated in this research landscape as consumers, architects, and arbiters and we engage in these roles in collaboration with others. This provides a useful vantage point from which to provide commentary on key elements which can cause frustration for would-be authors and reviewers of qualitative research papers [ 19 ].

In the discussion of a qualitative paper, ECRs are encouraged to make detailed comments about the contributions of their research and whether these reinforce, extend, or challenge existing understandings based on an analysis that is theoretically or socially significant [ 20 ]. As an example, Barratt et al., found important data to inform the training of medical interns in the use of personal protective equipment during the COVID 19 pandemic [ 21 ]. ECRs are also expected to address the “so what” question which relates to the the consequence of findings for policy, practice and theory. Authors will need to explicitly outline the practical, theoretical or methodological implications of the study findings in a way that is actionable, thereby enhancing relevance and plausibility. For example, Burgess et al., presented their discussion according to four themes and outlined associated implications for individuals and institutions [ 22 ]. A balanced view of the research can be presented by ensuring there is congruence between the data and the claims made and searching the data and/or literature for evidence that disconfirms the findings. ECRs will also need to put forward the sources of uncertainty (rather than limitations) in their research and argue what these may mean for the interpretations made and how the contributions to knowledge could be adopted by others in different contexts [ 23 ]. This links to the plausibility and transparency elements.

In conclusion

Qualitative research is underpinned by specific philosophical assumptions, quality criteria and a lexicon, which ECRs and reviewers need to be mindful of as they navigate the qualitative manuscript writing and reviewing processes. We hope that the guidance provided here is helpful for ECRs in preparing submissions and for reviewers in making informed decisions and providing quality feedback.

Authors’ contributions

CR and KK wrote the first draft. All three authors contributed to severally revising the manuscript. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

- 1. Silverman D. Introducing Qualitative Research in Silverman D (Ed) Qualitative Research, 4th Edn. London: Sage; 1984. p. 3–14.

- 2. Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19(6):349–357. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 3. Tai J, Ajjawi R. Undertaking and reporting qualitative research. Clin Teach. 2016;13(3):175–182. doi: 10.1111/tct.12552. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 4. Lincoln YS, Guba EG. Naturalistic inquiry. Beverly Hills: Sage Publications; 1985. p. 1995. [ Google Scholar ]

- 5. Patton MQ. Qualitative research & evaluation methods: integrating theory and practice. 4th Edn. Thousan Oaks: Sage publications; 2014.

- 6. Braun V, Clarke V. Successful qualitative research: a practical guide for beginners. London: Sage; 2013.

- 7. Lingard L. Joining a conversation: the problem/gap/hook heuristic. Perspect Med Educ. 2015;4(5):252–253. doi: 10.1007/s40037-015-0211-y. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 8. Cohen L, Manion L, Morrison K. Research Methods in Education. 8th Edn. Abingdon: Routledge; 2019.

- 9. Brown MEL, Dueñas AN. A medical science Educator’s guide to selecting a research paradigm: building a basis for better research. Med Sci Educ. 2020;30(1):545–553. doi: 10.1007/s40670-019-00898-9. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 10. Ommering BWC, Wijnen-Meijer M, Dolmans DHJM, Dekker FW, van Blankenstein FM. Promoting positive perceptions of and motivation for research among undergraduate medical students to stimulate future research involvement: a grounded theory study. BMC Med Educ. 2020;20(1):204. doi: 10.1186/s12909-020-02112-6. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 11. Bradbury-Jones C, Taylor J, Herber O. How theory is used and articulated in qualitative research: development of a new typology. Soc Sci Med. 2014;120:135–141. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.09.014. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 12. Reeves S, Albert M, Kuper A, Hodges BD. Why use theories in qualitative research? BMJ. 2008;7;337:a949. 10.1136/bmj.a949. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ]

- 13. Kumar K, Greenhill J. Factors shaping how clinical educators use their educational knowledge and skills in the clinical workplace: a qualitative study. BMC Med Educ. 2016;16(1):68. doi: 10.1186/s12909-016-0590-8. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 14. Touchie C, Humphrey-Murto S, Varpio L. Teaching and assessing procedural skills: a qualitative study. BMC Med Educ. 2013;13(1):69. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-13-69. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 15. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 16. Yardley S, Dornan T. Kirkpatrick’s levels and education ‘evidence’. Med Educ. 2012;46(1):97–106. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2011.04076.x. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 17. Palmer RC, Samson R, Triantis M, Mullan ID. Development and evaluation of a web-based breast cancer cultural competency course for primary healthcare providers. BMC Med Educ. 2011;11(1):59. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-11-59. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 18. Bindels E, Verberg C, Scherpbier A, Heeneman S, Lombarts K. Reflection revisited: how physicians conceptualize and experience reflection in professional practice – a qualitative study. BMC Med Educ. 2018;18(1):105. doi: 10.1186/s12909-018-1218-y. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 19. Finlay L. “Outing” the researcher: the provenance, process, and practice of reflexivity. Qual Health Res. 2002;12:531–545. doi: 10.1177/104973202129120052. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 20. Watling CJ, Lingard L. Grounded theory in medical education research: AMEE guide no. 70. Med Teach. 2012;34(10):850–861. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2012.704439. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 21. Barratt R, Wyer M, Hor S-y, Gilbert GL. Medical interns’ reflections on their training in use of personal protective equipment. BMC Med Educ. 2020;20(1):328. doi: 10.1186/s12909-020-02238-7. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 22. Burgess A, Roberts C, Clark T, Mossman K. The social validity of a national assessment Centre for selection into general practice training. BMC Med Educ. 2014;14(1):261. doi: 10.1186/s12909-014-0261-6. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 23. Lingard L. The art of limitations. Perspect Med Educ. 2015;4(3):136–137. doi: 10.1007/s40037-015-0181-0. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- View on publisher site

- PDF (480.2 KB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical Numismatics

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Social History

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Language Acquisition

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Media

- Music and Culture

- Music and Religion

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Meta-Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Society

- Law and Politics

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Legal System - Costs and Funding

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Restitution

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Ethics

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Games

- Computer Security

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience