273 Strong Verbs That’ll Spice Up Your Writing

Do you ever wonder why a grammatically correct sentence you’ve written just lies there like a dead fish?

I sure have.

Your sentence might even be full of those adjectives and adverbs your teachers and loved ones so admired in your writing when you were a kid.

But still the sentence doesn’t work.

Something simple I learned from The Elements of Style years ago changed the way I write and added verve to my prose. The authors of that little bible of style said: “Write with nouns and verbs, not with adjectives and adverbs.”

Even Mark Twain was quoted , regarding adjectives: “When in doubt, strike it out.”

That’s not to say there’s no place for adjectives. I used three in the title and first paragraph of this post alone.

The point is that good writing is more about well-chosen nouns and powerful verbs than it is about adjectives and adverbs, regardless what you were told as a kid.

There’s no quicker win for you and your manuscript than ferreting out and eliminating flabby verbs and replacing them with vibrant ones.

*Ready to take the next step as a writer? Grab Self-Editing Masterclass , a power-packed collection of video lessons and resources that gives you all the tools you’ll need to write crystal-clear prose you’ll be confident to show agents and publishers. Best of all? You can get through all the material in under two hours.*

- How To Know Which Verbs Need Replacing

Your first hint is your own discomfort with a sentence. Odds are it features a snooze-inducing verb.

As you hone your ferocious self-editing skills, train yourself to exploit opportunities to replace a weak verb for a strong one .

At the end of this post I suggest a list of 273 vivid verbs you can experiment with to replace tired ones.

What constitutes a tired verb? Here’s what to look for:

- 3 Types of Verbs to Beware of in Your Prose

1. State-of-being verbs

These are passive as opposed to powerful:

Am I saying these should never appear in your writing? Of course not. You’ll find them in this piece. But when a sentence lies limp, you can bet it contains at least one of these. Determining when a state-of-being verb is the culprit creates a problem—and finding a better, more powerful verb to replace it— is what makes us writers. [Note how I replaced the state-of-being verbs in this paragraph.]

Resist the urge to consult a thesaurus for the most exotic verb you can find. I consult such references only for the normal word that carries power but refuses to come to mind.

I would suggest even that you consult my list of powerful verbs only after you have exhaust ed all efforts to come up with one on your own. You want Make your prose to be your own creation, not yours plus Roget or Webster or Jenkins. [See how easy they are to spot and fix?]

Impotent: The man was walking on the platform.

Powerful: The man strode along the platform.

Impotent: Jim is a lover of country living.

Powerful: Jim treasures country living.

Impotent: There are three things that make me feel the way I do…

Powerful: Three things convince me…

2. Verbs that rely on adverbs

Powerful verbs are strong enough to stand alone.

The fox ran quickly dashed through the forest.

She menacingly looked glared at her rival.

He secretly listened eavesdropped while they discussed their plans.

3. Verbs with -ing suffixes

Before: He was walking…

After: He walked…

Before: She was loving the idea of…

After: She loved the idea of…

Before: The family was starting to gather…

After: The family started to gather…

- The Strong Verbs List

- Disillusion

- Reverberate

- Revolutionize

- Supercharge

- Transfigure

Faith-Based Words and Phrases

What You and I Can Learn From Patricia Raybon

A Guest Blog from Stephen King—Yes, that Stephen King

Before you go, be sure to grab my FREE guide:

How to Write a Book: Everything You Need to Know in 20 Steps

Just tell me where to send it:

Great!

Where should i send your free pdf.

50 Verbs of Analysis for English Academic Essays

Note: this list is for advanced English learners (CEFR level B2 or above). All definitions are from the Cambridge Dictionary online .

Definition: to have an influence on someone or something, or to cause a change in someone or something.

Example: Experts agree that coffee affects the body in ways we have not yet studied.

Definition: to increase the size or effect of something.

Example: It has been shown that this drug amplifies the side effects that were experienced by patients in previous trials.

Definition: to say that something is certainly true .

Example: Smith asserts that his findings are valid, despite criticism by colleagues.

Characterizes

Definition: Something that characterizes another thing is typical of it.

Example: His early paintings are characterized by a distinctive pattern of blue and yellow.

Definition: to say that something is true or is a fact , although you cannot prove it and other people might not believe it.

Example: Smith claims that the study is the first of its kind, and very different from the 2015 study he conducted.

Definition: to make something clear or easier to understand by giving more details or a simpler explanation .

Example: The professor clarified her statement with a later, more detailed, statement.

Definition: t o collect information from different places and arrange it in a book , report , or list .

Example: After compiling the data, the scientists authored a ten-page paper on their study and its findings.

Definition: to judge or decide something after thinking carefully about it.

Example: Doctor Jensen concluded that the drug wasn’t working, so he switched his patient to a new medicine.

Definition: to prove that a belief or an opinion that was previously not completely certain is true .

Example: This new data confirms the hypothesis many researchers had.

Definition: to join or be joined with something else .

Example: By including the criticisms of two researchers, Smith connects two seemingly different theories and illustrates a trend with writers of the Romanticism period.

Differentiates

Definition: to show or find the difference between things that are compared .

Example: Smith differentiates between the two theories in paragraph 4 of the second part of the study.

Definition: to reduce or be reduced in s i ze or importance .

Example: The new findings do not diminish the findings of previous research; rather, it builds on it to present a more complicated theory about the effects of global warming.

Definition: to cause people to stop respecting someone or believing in an idea or person .

Example: The details about the improper research done by the institution discredits the institution’s newest research.

Definition: to show.

Example: Smith’s findings display the effects of global warming that have not yet been considered by other scientists.

Definition: to prove that something is not true .

Example: Scientists hope that this new research will disprove the myth that vaccines are harmful to children.

Distinguishes

Definition: to notice or understand the difference between two things, or to make one person or thing seem different from another.

Example: Our study seems similar to another one by Duke University: how can we distinguish ourselves and our research from this study?

Definition: to add more information to or explain something that you have said.

Example: In this new paper, Smith elaborates on theories she discussed in her 2012 book.

Definition: to represent a quality or an idea exactly .

Example: Shakespeare embodies English theater, but few can understand the antiquated (old) form of English that is used in the plays.

Definition: to copy something achieved by someone else and try to do it as well as they have.

Example: Although the study emulates some of the scientific methods used in previous research, it also offers some inventive new research methods.

Definition: to improve the quality , amount , or strength of something.

Example: The pharmaceutical company is looking for ways to enhance the effectiveness of its current drug for depression.

Definition: to make something necessary , or to involve something.

Example: The scientist’s study entails several different stages, which are detailed in the report.

Definition: to consider one thing to be the same as or equal to another thing.

Example: Findings from both studies equate; therefore, we can conclude that they are both accurate.

Establishes

Definition: to discover or get proof of something.

Example: The award establishes the main causes of global warming.

Definition: to make someone remember something or feel an emotion .

Example: The artist’s painting evokes the work of some of the painters from the early 1800s.

Definition: to show something.

Example: Some of the research study participants exhibit similar symptoms while taking the medicine.

Facilitates

Definition: to make something possible or easier .

Example: The equipment that facilitates the study is expensive and of high-quality.

Definition: the main or central point of something, especially of attention or interest .

Example: The author focuses on World War II, which is an era she hasn’t written about before.

Foreshadows

Definition: to act as a warning or sign of a future event .

Example: The sick bird at the beginning of the novel foreshadows the illness the main character develops later in the book.

Definition: to develop all the details of a plan for doing something.

Example: Two teams of scientists formulated the research methods for the study.

Definition: to cause something to exist .

Example: The study’s findings have generated many questions about this new species of frog in South America.

Definition: to attract attention to or emphasize something important .

Example: The author, Dr. Smith, highlights the need for further studies on the possible causes of cancer among farm workers.

Definition: to recognize a problem , need, fact , etc. and to show that it exists .

Example: Through this study, scientists were able to identify three of the main factors causing global warming.

Illustrates

Definition: to show the meaning or truth of something more clearly , especially by giving examples .

Example: Dr. Robin’s study illustrates the need for more research on the effects of this experimental drug.

Definition: to communicate an idea or feeling without saying it directly .

Example: The study implies that there are many outside factors (other than diet and exercise) which determine a person’s tendency to gain weight.

Incorporates

Definition: to include something as part of something larger .

Example: Dr. Smith incorporates research findings from 15 other studies in her well-researched paper.

Definition: to show, point , or make clear in another way.

Example: Overall, the study indicates that there is no real danger (other than a lack of sleep) to drinking three cups of coffee per day.

Definition: to form an opinion or guess that something is true because of the information that you have.

Example: From this study about a new medicine, we can infer that it will work similarly to other drugs that are currently being sold.

Definition: to tell someone about parti c ular facts .

Example: Dr. Smith informs the reader that there are some issues with this study: the oddly rainy weather in 2017 made it difficult for them to record the movements of the birds they were studying.

Definition: to suggest , without being direct , that something unpleasant is true .

Example: In addition to the reported conclusions, the study insinuates that there are many hidden dangers to driving while texting.

Definition: to combine two or more things in order to become more effective .

Example: The study about the popularity of social media integrates Facebook and Instagram hashtag use.

Definition: to not have or not have enough of something that is needed or wanted .

Example: What the study lacks, I believe, is a clear outline of the future research that is needed.

Legitimizes

Definition: to make something legal or acceptable .

Example: Although the study legitimizes the existence of global warming, some will continue to think it is a hoax.

Definition: to make a problem bigger or more important .

Example: In conclusion, the scientists determined that the new pharmaceutical actually magnifies some of the symptoms of anxiety.

Definition: something that a copy can be based on because it is an extremely good example of its type .

Example: The study models a similar one from 1973, which needed to be redone with modern equipment.

Definition: to cause something to have no effect .

Example: This negates previous findings that say that sulphur in wine gives people headaches.

Definition: to not give enough c a re or attention to people or things that are your responsibility .

Example: The study neglects to mention another study in 2015 that had very different findings.

Definition: to make something difficult to discover and understand .

Example: The problems with the equipment obscures the study.

Definition: a description of the main facts about something.

Example: Before describing the research methods, the researchers outline the need for a study on the effects of anti-anxiety medication on children.

Definition: to fail to notice or consider something or someone.

Example: I personally feel that the study overlooks something very important: the participants might have answered some of the questions incorrectly.

Definition: to happen at the same time as something else , or be similar or equal to something else .

Example: Although the study parallels the procedures of a 2010 study, it has very different findings.

Converse International School of Languages offers an English for Academic Purposes course for students interested in improving their academic English skills. Students may take this course, which is offered in the afternoon for 12 weeks, at both CISL San Diego and CISL San Francisco . EAP course graduates can go on to CISL’s Aca demic Year Abroad program, where students attend one semester at a California Community College. Through CISL’s University Pathway program, EAP graduates may also attend college or university at one of CISL’s Pathway Partners. See the list of 25+ partners on the CISL website . Contact CISL for more information.

Power Verbs for Essays (With Examples)

By The ProWritingAid Team

Adding power verbs to your academic paper will improve your reader’s experience and bring more impact to the arguments you make.

While the arguments themselves are the most important elements of any successful academic paper, the structure of those arguments and the language that is used influence how the paper is received.

Academic papers have strict formal rules, but as long as these are followed, there is still plenty of scope to make the key points of the paper stand out through effective use of language and more specifically, the effective use of power verbs.

Power verbs are verbs that indicate action and have a more positive and confident tone. Using them brings strength and confidence to the arguments you are making, while also bringing variation to your sentences and making your writing more interesting to the reader.

The best academic papers will use such verbs to support their arguments or concepts, so it is important that your paper contains at least three power verbs.

ProWritingAid will check your writing for power verbs and will notify you if you have less than three throughout your whole academic paper.

Power Verbs Boost Ideas

Examples of power verbs.

Academic papers of all disciplines are often filled with overlong and complicated sentences that are attempting to convey specific ideas and concepts. Active and powerful verbs are useful both to the reader and the author of the paper.

For the reader who is trying to tackle these ideas and concepts, the power verbs provide clarity and purpose. Compare the following sentences:

- This paper will say that there were two reasons for the start of the civil war.

- This paper asserts that there were two reasons for the start of the civil war.

Clearly the second sentence is more confident, direct, and authoritative because it has replaced the dull ‘says’ with ‘asserts.’ For the writer, the power verb expresses confidence in the idea being presented.

The following are examples of power verbs that are useful in academic writing, both for supporting an argument and for allowing you to vary the language you use.

Power Verbs for Analysis: appraise, define, diagnose, examine, explore, identify, interpret, investigate, observe.

Power Verbs to Introduce a Topic: investigate, outline, survey, question, feature.

Power Verbs to Agree with Existing Studies: indicate, suggest, confirm, corroborate, underline, identify, impart, maintain, substantiate, support, validate, acknowledge, affirm, assert.

Power Verbs to Disagree with Existing Studies: reject, disprove, debunk, question, challenge, invalidate, refute, deny, dismiss, disregard, object to, oppose.

Power Verbs to Infer: extract, approximate, surmise, deduce.

Power Verbs for Cause and Effect : impacts, compels, generates, incites, influences, initiates, prompts, stimulates, provokes, launches, introduces, advances.

Legal Power Verbs: sanctions, consents, endorses, disallows, outlaws, prohibits, precludes, protects, bans, licenses, authorizes.

Power Verbs that Say: convey, comment, state, establish, elaborate, identify, propose.

Power Verbs that Show: reveal, display, highlight, depict, portray, illustrate.

Be confident about grammar

Check every email, essay, or story for grammar mistakes. Fix them before you press send.

The ProWritingAid Team

The most successful people in the world have coaches. Whatever your level of writing, ProWritingAid will help you achieve new heights. Exceptional writing depends on much more than just correct grammar. You need an editing tool that also highlights style issues and compares your writing to the best writers in your genre. ProWritingAid helps you find the best way to express your ideas.

Get started with ProWritingAid

Drop us a line or let's stay in touch via:

New Courses Open for Enrolment! Find Out More

- 40 Useful Words and Phrases for Top-Notch Essays

To be truly brilliant, an essay needs to utilise the right language. You could make a great point, but if it’s not intelligently articulated, you almost needn’t have bothered.

Developing the language skills to build an argument and to write persuasively is crucial if you’re to write outstanding essays every time. In this article, we’re going to equip you with the words and phrases you need to write a top-notch essay, along with examples of how to utilise them.

It’s by no means an exhaustive list, and there will often be other ways of using the words and phrases we describe that we won’t have room to include, but there should be more than enough below to help you make an instant improvement to your essay-writing skills.

If you’re interested in developing your language and persuasive skills, Oxford Royale offers summer courses at its Oxford Summer School , Cambridge Summer School , London Summer School , San Francisco Summer School and Yale Summer School . You can study courses to learn english , prepare for careers in law , medicine , business , engineering and leadership.

General explaining

Let’s start by looking at language for general explanations of complex points.

1. In order to

Usage: “In order to” can be used to introduce an explanation for the purpose of an argument. Example: “In order to understand X, we need first to understand Y.”

2. In other words

Usage: Use “in other words” when you want to express something in a different way (more simply), to make it easier to understand, or to emphasise or expand on a point. Example: “Frogs are amphibians. In other words, they live on the land and in the water.”

3. To put it another way

Usage: This phrase is another way of saying “in other words”, and can be used in particularly complex points, when you feel that an alternative way of wording a problem may help the reader achieve a better understanding of its significance. Example: “Plants rely on photosynthesis. To put it another way, they will die without the sun.”

4. That is to say

Usage: “That is” and “that is to say” can be used to add further detail to your explanation, or to be more precise. Example: “Whales are mammals. That is to say, they must breathe air.”

5. To that end

Usage: Use “to that end” or “to this end” in a similar way to “in order to” or “so”. Example: “Zoologists have long sought to understand how animals communicate with each other. To that end, a new study has been launched that looks at elephant sounds and their possible meanings.”

Adding additional information to support a point

Students often make the mistake of using synonyms of “and” each time they want to add further information in support of a point they’re making, or to build an argument. Here are some cleverer ways of doing this.

6. Moreover

Usage: Employ “moreover” at the start of a sentence to add extra information in support of a point you’re making. Example: “Moreover, the results of a recent piece of research provide compelling evidence in support of…”

7. Furthermore

Usage:This is also generally used at the start of a sentence, to add extra information. Example: “Furthermore, there is evidence to suggest that…”

8. What’s more

Usage: This is used in the same way as “moreover” and “furthermore”. Example: “What’s more, this isn’t the only evidence that supports this hypothesis.”

9. Likewise

Usage: Use “likewise” when you want to talk about something that agrees with what you’ve just mentioned. Example: “Scholar A believes X. Likewise, Scholar B argues compellingly in favour of this point of view.”

10. Similarly

Usage: Use “similarly” in the same way as “likewise”. Example: “Audiences at the time reacted with shock to Beethoven’s new work, because it was very different to what they were used to. Similarly, we have a tendency to react with surprise to the unfamiliar.”

11. Another key thing to remember

Usage: Use the phrase “another key point to remember” or “another key fact to remember” to introduce additional facts without using the word “also”. Example: “As a Romantic, Blake was a proponent of a closer relationship between humans and nature. Another key point to remember is that Blake was writing during the Industrial Revolution, which had a major impact on the world around him.”

12. As well as

Usage: Use “as well as” instead of “also” or “and”. Example: “Scholar A argued that this was due to X, as well as Y.”

13. Not only… but also

Usage: This wording is used to add an extra piece of information, often something that’s in some way more surprising or unexpected than the first piece of information. Example: “Not only did Edmund Hillary have the honour of being the first to reach the summit of Everest, but he was also appointed Knight Commander of the Order of the British Empire.”

14. Coupled with

Usage: Used when considering two or more arguments at a time. Example: “Coupled with the literary evidence, the statistics paint a compelling view of…”

15. Firstly, secondly, thirdly…

Usage: This can be used to structure an argument, presenting facts clearly one after the other. Example: “There are many points in support of this view. Firstly, X. Secondly, Y. And thirdly, Z.

16. Not to mention/to say nothing of

Usage: “Not to mention” and “to say nothing of” can be used to add extra information with a bit of emphasis. Example: “The war caused unprecedented suffering to millions of people, not to mention its impact on the country’s economy.”

Words and phrases for demonstrating contrast

When you’re developing an argument, you will often need to present contrasting or opposing opinions or evidence – “it could show this, but it could also show this”, or “X says this, but Y disagrees”. This section covers words you can use instead of the “but” in these examples, to make your writing sound more intelligent and interesting.

17. However

Usage: Use “however” to introduce a point that disagrees with what you’ve just said. Example: “Scholar A thinks this. However, Scholar B reached a different conclusion.”

18. On the other hand

Usage: Usage of this phrase includes introducing a contrasting interpretation of the same piece of evidence, a different piece of evidence that suggests something else, or an opposing opinion. Example: “The historical evidence appears to suggest a clear-cut situation. On the other hand, the archaeological evidence presents a somewhat less straightforward picture of what happened that day.”

19. Having said that

Usage: Used in a similar manner to “on the other hand” or “but”. Example: “The historians are unanimous in telling us X, an agreement that suggests that this version of events must be an accurate account. Having said that, the archaeology tells a different story.”

20. By contrast/in comparison

Usage: Use “by contrast” or “in comparison” when you’re comparing and contrasting pieces of evidence. Example: “Scholar A’s opinion, then, is based on insufficient evidence. By contrast, Scholar B’s opinion seems more plausible.”

21. Then again

Usage: Use this to cast doubt on an assertion. Example: “Writer A asserts that this was the reason for what happened. Then again, it’s possible that he was being paid to say this.”

22. That said

Usage: This is used in the same way as “then again”. Example: “The evidence ostensibly appears to point to this conclusion. That said, much of the evidence is unreliable at best.”

Usage: Use this when you want to introduce a contrasting idea. Example: “Much of scholarship has focused on this evidence. Yet not everyone agrees that this is the most important aspect of the situation.”

Adding a proviso or acknowledging reservations

Sometimes, you may need to acknowledge a shortfalling in a piece of evidence, or add a proviso. Here are some ways of doing so.

24. Despite this

Usage: Use “despite this” or “in spite of this” when you want to outline a point that stands regardless of a shortfalling in the evidence. Example: “The sample size was small, but the results were important despite this.”

25. With this in mind

Usage: Use this when you want your reader to consider a point in the knowledge of something else. Example: “We’ve seen that the methods used in the 19th century study did not always live up to the rigorous standards expected in scientific research today, which makes it difficult to draw definite conclusions. With this in mind, let’s look at a more recent study to see how the results compare.”

26. Provided that

Usage: This means “on condition that”. You can also say “providing that” or just “providing” to mean the same thing. Example: “We may use this as evidence to support our argument, provided that we bear in mind the limitations of the methods used to obtain it.”

27. In view of/in light of

Usage: These phrases are used when something has shed light on something else. Example: “In light of the evidence from the 2013 study, we have a better understanding of…”

28. Nonetheless

Usage: This is similar to “despite this”. Example: “The study had its limitations, but it was nonetheless groundbreaking for its day.”

29. Nevertheless

Usage: This is the same as “nonetheless”. Example: “The study was flawed, but it was important nevertheless.”

30. Notwithstanding

Usage: This is another way of saying “nonetheless”. Example: “Notwithstanding the limitations of the methodology used, it was an important study in the development of how we view the workings of the human mind.”

Giving examples

Good essays always back up points with examples, but it’s going to get boring if you use the expression “for example” every time. Here are a couple of other ways of saying the same thing.

31. For instance

Example: “Some birds migrate to avoid harsher winter climates. Swallows, for instance, leave the UK in early winter and fly south…”

32. To give an illustration

Example: “To give an illustration of what I mean, let’s look at the case of…”

Signifying importance

When you want to demonstrate that a point is particularly important, there are several ways of highlighting it as such.

33. Significantly

Usage: Used to introduce a point that is loaded with meaning that might not be immediately apparent. Example: “Significantly, Tacitus omits to tell us the kind of gossip prevalent in Suetonius’ accounts of the same period.”

34. Notably

Usage: This can be used to mean “significantly” (as above), and it can also be used interchangeably with “in particular” (the example below demonstrates the first of these ways of using it). Example: “Actual figures are notably absent from Scholar A’s analysis.”

35. Importantly

Usage: Use “importantly” interchangeably with “significantly”. Example: “Importantly, Scholar A was being employed by X when he wrote this work, and was presumably therefore under pressure to portray the situation more favourably than he perhaps might otherwise have done.”

Summarising

You’ve almost made it to the end of the essay, but your work isn’t over yet. You need to end by wrapping up everything you’ve talked about, showing that you’ve considered the arguments on both sides and reached the most likely conclusion. Here are some words and phrases to help you.

36. In conclusion

Usage: Typically used to introduce the concluding paragraph or sentence of an essay, summarising what you’ve discussed in a broad overview. Example: “In conclusion, the evidence points almost exclusively to Argument A.”

37. Above all

Usage: Used to signify what you believe to be the most significant point, and the main takeaway from the essay. Example: “Above all, it seems pertinent to remember that…”

38. Persuasive

Usage: This is a useful word to use when summarising which argument you find most convincing. Example: “Scholar A’s point – that Constanze Mozart was motivated by financial gain – seems to me to be the most persuasive argument for her actions following Mozart’s death.”

39. Compelling

Usage: Use in the same way as “persuasive” above. Example: “The most compelling argument is presented by Scholar A.”

40. All things considered

Usage: This means “taking everything into account”. Example: “All things considered, it seems reasonable to assume that…”

How many of these words and phrases will you get into your next essay? And are any of your favourite essay terms missing from our list? Let us know in the comments below, or get in touch here to find out more about courses that can help you with your essays.

At Oxford Royale Academy, we offer a number of summer school courses for young people who are keen to improve their essay writing skills. Click here to apply for one of our courses today, including law , business , medicine and engineering .

Comments are closed.

KathySteinemann.com: Free Resources for Writers

Word lists, cheat sheets, and sometimes irreverent reviews of writing rules. kathy steinemann is the author of the writer's lexicon series..

Strong Verbs Cheat Sheet: A Word List for Writers

Ambiguous Verbs Dilute Writing

Which of these sentences prompts a more powerful image?

He walked to the door.

He plodded to the door.

The second example shows us a character who might be tired, lonely, or depressed. One verb paints a powerful picture.

Some sources insist that writers should show — almost to the exclusion of tell. A frequent consequence of this approach is word bloat . However, well-chosen verbs deliver precise meanings. They invigorate narrative without increasing word count.

Harness Strong Verbs and Their Diverse Nuances

The child was under her guardian’s care.

This statement offers a basic fact but no details that might further the story.

Review the following three revisions. Each one replaces was with a stronger alternative:

The child thrived under her guardian’s care.

This child is healthy. We intuit a caring guardian who probably feeds the girl well and attends to her physical and emotional needs.

The child endured under her guardian’s care.

The second child might be alive in spite of her guardian’s care. Perhaps he abuses her physically or emotionally.

The child subsisted under her guardian’s care.

The third child survives, albeit at a minimal level. Perhaps the guardian doesn’t provide a healthy diet or a clean environment.

Let’s Evaluate Another Scenario

Alyssa walked toward the table while she looked at the grandfather clock next to the china cabinet. The clock chimed midnight. She pulled out her phone and touched the screen. Three hours. Henry had been gone for three hours.

Here, we see a woman who is waiting for Henry. However, we don’t know whether she’s worried or angry . Let’s change the underlined verbs:

Alyssa trudged toward the table while she stared at the grandfather clock next to the china cabinet. The clock chimed midnight. She dragged out her phone and fondled the screen. Three hours. Henry had been gone for three hours.

The strong verbs show an Alyssa who seems worried, perhaps even depressed. She fondles the screen of her phone. Maybe her screensaver is a photo of Henry.

Alyssa stomped toward the table while she glared at the grandfather clock next to the china cabinet. The clock chimed midnight. She jerked out her phone and jabbed the screen. Three hours. Henry had been gone for three hours.

Do you have any doubt that this Alyssa is angry?

A Final Set of Examples

Sparks appeared in the hallway, and smoke blew into the coffee room. Trent went to the fire alarm and pulled the handle. He listened . No sound from the alarm. He moved toward the emergency exit.

In view of the circumstances, Trent seems illogically nonchalant.

Sparks erupted in the hallway, and smoke billowed into the coffee room. Trent raced to the fire alarm and wrenched the handle. He concentrated . No sound from the alarm. He inched toward the emergency exit.

This Trent acts suitably anxious, but he exhibits care while he moves through the smoke toward the emergency exit.

The Cheat Sheet

The following list contains several common verbs, along with suggested alternatives.

appear: emerge, erupt, expand, flash into view, materialize, pop up, solidify, spread out, surface, take shape, unfold, unfurl, unwrap

be: bloom, blossom, endure, exist, flourish, last, live, manage, persevere, persist, prevail, remain, stay, subsist, survive, thrive

begin: activate, commence, create, initiate, launch, originate [Do you need begin, start, or their relatives? Writing is usually stronger without them.]

believe: accept, admit, affirm, conjecture, hope, hypothesize, imagine, postulate, presume, speculate, surmise, suspect, trust

blow: billow, blast, curl, drift, eddy, flow, flutter, fly, gasp, glide, gust, puff, roar, sail, scud, sough, storm, surge, swell, undulate, waft, whirl

break: crush, decimate, demolish, destroy, disintegrate, flatten, fracture, fragment, raze, shatter, smash, snap, splinter, split

bring: bear, carry, cart, drag, draggle, ferry, fetch, forward, haul, heave, heft, lug, relay, schlep, send, shuttle, tow, transport

close: bang shut, bar, block, blockade, bolt, bung, cork, fasten, latch, lock, obstruct, plug, seal, secure, slam, squeeze shut, stopper

come: advance, approach, arrive, draw near, drive, enter, fly, near, proceed, reach, show up, slip in, sneak, travel, turn up

cry: bawl, bellow, bleat, blubber, howl, keen, mewl, moan, snivel, scream, sob, squall, squeal, wail, weep, whimper, whine, yelp

disappear: atomize, crumble, disband, disperse, dissipate, dissolve, evaporate, fade away, fizzle out, melt away, scatter, vaporize

do: accomplish, achieve, attempt, complete, consummate, enact, execute, fulfill, implement, perform, shoulder, undertake

eat: bolt, chomp, consume, devour, dine, gobble, gnaw at, gorge, guzzle, ingest, inhale, munch, nibble, pick at, scarf, wolf down

feel (1): appreciate, bear, encounter, endure, experience, face, tolerate, stand, suffer, suspect, undergo, weather, withstand

feel (2): brush, caress, finger, fondle, grope, knead, manipulate, massage, palpate, pat, paw, poke, press, prod, rub, stroke, tap

get: annex, acquire, appropriate, attain, capture, clear, collect, earn, gain, gather, gross, land, procure, purchase, score, secure, steal, win

give: award, bequeath, bestow, confer, contribute, deliver, donate, grant, lend, offer, present, proffer, turn over, volunteer, vouchsafe

go: abscond, bolt, escape, exit, flee, fly, hightail it, journey, retire, retreat, sally, scram, set out, split, travel, vamoose, withdraw

have: boast, brandish, conserve, control, display, enjoy, flaunt, hoard, husband, keep, maintain, own, possess, preserve, retain

help: abet, aid, alleviate, assist, augment, back, bolster, comfort, encourage, improve, relieve, rescue, sanction, succor, support

hold: capture, clasp, clench, cling, clutch, cuddle, embrace, enfold, envelop, grapple, grasp, grip, hug, pinch, seize, snatch, squeeze

jump: bob, bobble, bounce, bound, caper, cavort, clear, frisk, hop, hurdle, jolt, jounce, leap, leapfrog, rocket, romp, skip, spring, vault

know: appreciate, comprehend, fathom, follow, grasp, identify, perceive, realize, recollect, recognize, register, twig, understand

let: accept, acquiesce, allow, approve, authorize, consent, empower, enable, facilitate, license, okay, permit, sanction, suffer, tolerate

like: admire, adore, adulate, cherish, dote, enjoy, esteem, honor, idolize, relish, respect, revere, savor, treasure, venerate, worship

listen: earwig, concentrate, eavesdrop, focus on, heed, monitor, overhear, pay attention, perk the ears, snoop, spy, take note

look: eye, examine, gape, gawk, gaze, glance, glare, goggle, inspect, ogle, peek, peer, rubberneck, scrutinize, stare, study, survey

move: advance, budge, climb, creep, edge, gallivant, inch, progress, reposition, shift, sidle, slide, slink, slip, slither, stir, tiptoe, travel

occur: arise, befall, betide, chance, coalesce, crop up, crystalize, ensue, eventuate, manifest, supervene, surface, transpire

pull: drag, draw, extract, haul, jerk, lug, mine, pluck, schlep, seize, snatch, tow, trawl, troll, tug, tweak, twist, withdraw, wrench, yank

put: arrange, deposit, drop, dump, lay, leave, lodge, organize, park, place, plant, plonk, plunk, position, push, release, stash, wedge

run: bolt, charge, dart, dash, gallop, hurtle, jog, lope, race, rush, scamper, scurry, scoot, shoot, speed, sprint, tear, trot, zip, zoom

see: detect, differentiate, discover, distinguish, glimpse, identify, notice, observe, perceive, recognize, sight, spot, view, witness

shake: agitate, churn, convulse, jiggle, joggle, jostle, judder, quake, quiver, rock, seethe, shudder, sway, tremble, vibrate, wobble

sit: alight, collapse into, drop into, fall into, flop, hang, loll, lounge, park, perch, recline, rest, roost, settle, slump into, sprawl, straddle

smile: beam, brighten, dimple, flash the teeth, glow, grin, leer, light up, radiate delight, simper, smirk, sneer, snigger, sparkle, twinkle

speak: articulate, chat, chatter, converse, enunciate, gossip, mumble, murmur, natter, orate, parley, proclaim, verbalize, vocalize, whisper

stand (1): abide, bear, brook, countenance, endure, live through, suffer through, stomach, survive, tolerate, undergo, weather

stand (2): arise, bob up, get to one’s feet, get up, jump out of one’s seat, jump up, leap up, push out of one’s seat, rise, rise up, spring up

stand (3): peacock, pose, position oneself, posture, seesaw, shift from foot to foot, strike a pose, sway, teeter, teeter-totter, wobble

take: carry, cart, conduct, convey, deliver, escort, ferry, guide, marshal, shepherd, shoulder, steer, tote, transfer, transport, usher

talk: argue, blather, burble, confer, converse, debate, deliberate, discuss, lecture, maunder, prate, splutter, sputter, stammer, stutter

tell: announce, apprise, assert, avow, chronicle, claim, declare, describe, disclose, divulge, maintain, narrate, proclaim, report, reveal

think: conceive, concoct, contemplate, deliberate, dream, envisage, imagine, invent, meditate, muse, ponder, reflect, visualize, weigh

touch: caress, elbow, finger, fondle, graze, handle, jab, jostle, manhandle, mess, pat, scrape, scratch, shove, stroke, tap, tousle

turn: circle, gyrate, gyre, pirouette, pivot, reel, revolve, rotate, spin, spiral, swivel, twirl, twist, twizzle, wheel, whip around, whirl

understand: absorb, believe, cognize, comprehend, conclude, decipher, fathom, grasp, interpret, make out, make sense of, unravel

use: apply, channel, deploy, employ, establish, exercise, exploit, harness, maneuver, manipulate, practice, ply, utilize, wield

walk: amble, dance, drift, march, meander, parade, patrol, plod, promenade, saunter, slog, stomp, stroll, trek, tromp, trudge, wander

watch: eyeball, follow, guard, inspect, observe, police, protect, safeguard, scan, scrutinize, stalk, study, surveil, survey, track, view

work: aspire, drudge, endeavor, exert oneself, fight, grind, labor, slog, skivvy, strain, strive, struggle, sweat, toil, travail, wrestle

Ready for a Few Verb Aerobics?

Replace the underlined words with stronger choices.

With a scowl on her face , Endora put her arms across her chest and looked at Samantha. “You haven’t looked like that since your father won the Mr. Universe Pageant two centuries ago. What’s up?”

“Oh, nothing.” Samantha smiled . “Darrin just received a promotion, and we’re going to the Bahamas to celebrate.”

“Goodie. I can babysit while you’re gone.”

“Sorry, Mom. The kids are going with us.”

A thunderclap sounded . The house shook . Endora looked at her daughter. “They’re what?”

Suggested solution

Endora crossed her arms and scowled at Samantha. “You haven’t looked like that since your father won the Mr. Universe Pageant two centuries ago. What’s up?”

“Oh, nothing.” Samantha grinned . “Darrin just received a promotion, and we’re going to the Bahamas to celebrate.”

A thunderclap boomed . The house juddered . Endora glared at her daughter. “They’re what?”

Notes: Put her arms across her chest becomes crossed her arms . Dialogue remains as is to seem realistic, including Samantha’s repetition of going . The short sentences in the final paragraph speed the action and amplify the tension.

What’s that noise? Angela turned around. She listened .

Maximus appeared in the mist. She moved toward him — close, closer. She touched his arm. He spoke so quietly she couldn’t understand his words.

Puzzled, she looked into his eyes . He looked back with opaque amber orbs.

She shook .

What’s that noise? Angela whipped around. She concentrated .

Maximus materialized in the mist. She inched toward him — close, closer — and caressed his arm. He mumbled so quietly she couldn’t decipher his words.

Puzzled, she peered into his eyes. He stared back with opaque amber orbs.

She trembled .

Notes: Each verb in the suggested solution was selected from the cheat sheet.

Timmy put his tooth under his pillow and smiled at Mummy. “When will the Tooth Fairy come?”

She touched his forehead. “Not until you’re asleep. When she hears you snoring, she’ll sneak in. You’ll never see her, because she makes herself invisible.”

He closed his eyes and made a snoring noise .

Mummy touched his hair. “Nuh-uh. She’s too smart to fall for that.”

“Awwww. But I want to see her.”

Timmy stashed his tooth under his pillow and beamed at Mummy. “When will the Tooth Fairy come?”

She stroked his forehead. “Not until you’re asleep. When she hears you snoring, she’ll sneak in. You’ll never see her, because she makes herself invisible.”

He squeezed his eyes shut and faked a snore .

Mummy tousled his hair. “Nuh-uh. She’s too smart to fall for that.”

Notes: Once again, dialogue is untouched. The replacements are straightforward.

Discover more from KathySteinemann.com: Free Resources for Writers

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Type your email…

8 thoughts on “ Strong Verbs Cheat Sheet: A Word List for Writers ”

Very thoughtful and practical- I support your efforts.

Thanks, John.

I always enjoy your worthsmithing, Kathy, and this is one of your best. I’ll be sharing it with my writing critique group. Thanks! Lakota

Thanks, Lakota!

And thanks again for your advice on how writers can increase productivity and perseverance .

Thank you posting. I love it. Sounds strange I have aphasia a language disorder I got after having strokes. Did not take up writing before strokes wanted to. But now here I am and your message make purrrr fect sense. May I show my speech therapist? Copy it out and show her? blessings

Sure, Donna. Feel free to share. Do you find that your symptoms are improving with time and therapy?

Love your posts Kathy. Thank you. 🙂

Thanks for reading and sharing them, Debby!

Comments are closed.

280+ Strong Verbs: 3 Tips to Strengthen Your Verbs in Writing

by Joe Bunting | 0 comments

Strong verbs transform your writing from drab, monotonous, unclear, and amateurish to engaging, professional, and emotionally powerful.

Which is all to say, if you're not using strong verbs in your writing, you're missing one of the most important stylistic techniques.

Why listen to Joe? I've been a professional writer for more than a decade, writing in various different formats and styles. I've written formal nonfiction books, descriptive novels, humorous memoir chapters, and conversational but informative online articles (like this one!).

In short, I earn a living in part by writing (and revising) using strong verbs selected for each type of writing I work on. I hope you find the tips on verbs below useful! And if you want to skip straight to the verb list below, click here to see over 200 strong verbs.

Hemingway clung to a writing rule that said, “Use vigorous English.” In fact, Hemingway was more likely to use verbs than any other part of speech, far more than typical writing.

But what are strong verbs? And how do you avoid weak ones?

In this post, you'll learn the three best techniques to find weak verbs in your writing and replace them with strong ones. We'll also look at a list of the strongest verbs for each type of writing, including the strongest verbs to use.

What are Strong Verbs?

Strong verbs, in a stylistic sense, are powerful verbs that are specific and vivid verbs. They are most often in active voice and communicate action precisely.

The Top 7 Strong Verbs

Here are the top 7 I found when I reviewed a couple of my favorite books. See if you agree and tell me in the comments.

Think about the vivid and specific image each of these strong verbs conjures. Each one asserts precision.

It's true that writers will use descriptive verbs that best fit their character, story, and style, but it's interesting to note trends.

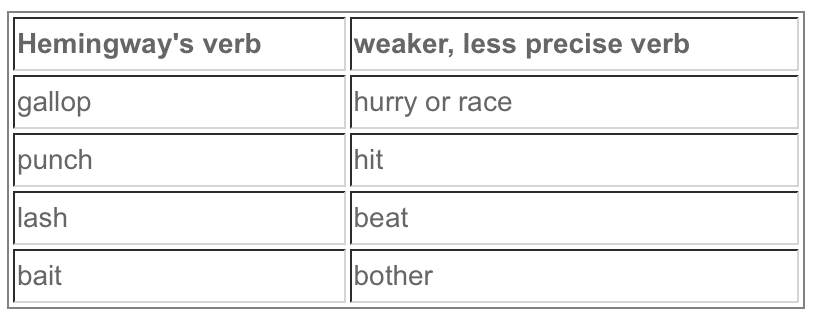

For example, Hemingway most often used verbs like: galloped, punched, lashed, and baited. Each of these verbs evokes a specific motion, as well as a tone. Consider how Hemingway's verbs stack up against weaker counterparts:

None of the weaker verbs are incorrect, but they don't pack the power of Hemingway's strong action verbs, especially for his story lines, characters, and style. These are verbs that are forward-moving and aggressive in tone. (Like his characters!)

Consider how those choices differ significantly than a few from Virginia Woolf's opening page of Mrs. Dalloway :

Notice how Woolf's choices create the vibrant, descriptive style that marks her experimental novel and its main character. Consider the difference between “perched” and “sat.” “Perched” suggests an image of a bird, balancing on a wire. Applied to people, it connotes an anxiousness or readiness to stand again. “Sat” is much less specific.

The strongest verbs for your own writing will depend on a few things: your story, the main character, the genre, and the style that is uniquely yours. How do you choose then? Let's look at three tips to edit out weak, boring verbs.

How to Edit for Strong Verbs FAST

So how do you root out those weak verbs and revise them quickly? Here are a few tips.

1. Search for Weak Verbs

All verbs can be strong if they're used in specific, detailed, and descriptive sentences.

The issue comes when verbs are overused, doing more work than they're intended for, watering down the writing.

Here are some verbs that tend to weaken your writing:

Did you notice that most of these are “to be” verbs? That's because “to be” verbs are linking verbs or state of being verbs. Their purpose is to describe conditions.

For example, in the sentence “They are happy,” the verb “are” is used to describe the state of the subject.

There's nothing particularly wrong with linking verbs. Writers who have a reputation for strong writing, like Ernest Hemingway or Cormac McCarthy, use linking verbs constantly.

The problem comes when you overuse them. Linking verbs tend to involve more telling vs. showing .

Strong verbs, on the other hand, are usually action verbs, like whack, said, ran, lassoed, and spit (see more in the list below).

The most important thing is to use the best verb for the context, while emphasizing specific, important details.

Take a look at the following example early into Hemingway's For Whom the Bell Tolls :

The young man, who was studying the country, took his glasses from the pocket of his faded, khaki flannel shirt, wiped the lenses with a handkerchief, screwed the eyepieces around until the boards of the mill showed suddenly clearly and he saw the wooden bench beside the door; the huge pile of sawdust that rose behind the open shed where the circular saw was , and a stretch of the flume that brought the logs down from the mountainside on the other bank of the stream.

I've highlighted all the verbs. You can see here that Hemingway does use the word “was,” but most of the verbs are action verbs, wiped, took, screwed, saw, etc. The result of this single sentence is that the audience pictures the scene with perfect clarity.

Here's another example from Naomi Novick's Deadly Education:

He was only a few steps from my desk chair, still hunched panting over the bubbling purplish smear of the soul-eater that was now steadily oozing into the narrow cracks between the floor tiles, the better to spread all over my room. The fading incandescence on his hands was illuminating his face, not an extraordinary face or anything: he had a big beaky nose that would maybe be dramatic one day when the rest of his face caught up, but for now was just too large, and his forehead was dripping sweat and plastered with his silver-grey hair that he hadn’t cut for three weeks too long.

Vivid right? You can see that again, she incorporates weaker verbs (was, had) into her writing, but the majority are highly descriptive action verbs like hunched, illuminating, spread, plastered, and dripping.

Don't be afraid of linking verbs, state verbs, or helping verbs, but emphasize action words to make your writing more powerful.

2. Remove Adverbs and Replace the Verbs to Make Them Stronger

Adverbs add more detail and qualifications to verbs or adjectives. You can spot them because they usually end in “-ly,” like the word “usually” in this sentence, or frequently, readily, happily, etc.

Adverbs get a bad rap from writers.

“I believe the road to hell is paved with adverbs,” Stephen King said.

“Adverbs are dead to me. They cannot excite me,” said Mark Twain .

“I was taught to distrust adjectives,” said Hemingway, “as I would later learn to distrust certain people in certain situations.”

Even Voltaire jumped in on the adverb dogpile, saying, “Adjectives are frequently the greatest enemy of the substantive.”

All of these writers, though, used adverbs when necessary. Still, the average writer uses them far more than they did.

Adverbs signal weak verbs. After all, why use two words, an adverb and a verb, when one strong verb can do.

Look at the following examples of adverbs with weak verbs replaced by stronger verbs:

- He ran quickly –> He sprinted

- She said loudly –> She shouted

- He ate hungrily –> He devoured his meal

- They talked quietly –> They whispered

Strive for simple, strong, clear language over padding your writing with more words.

You don't need to completely remove adverbs from your writing. Hemingway himself used them frequently. But cultivating a healthy distrust of adverbs seems to be a sign of wisdom among writers.

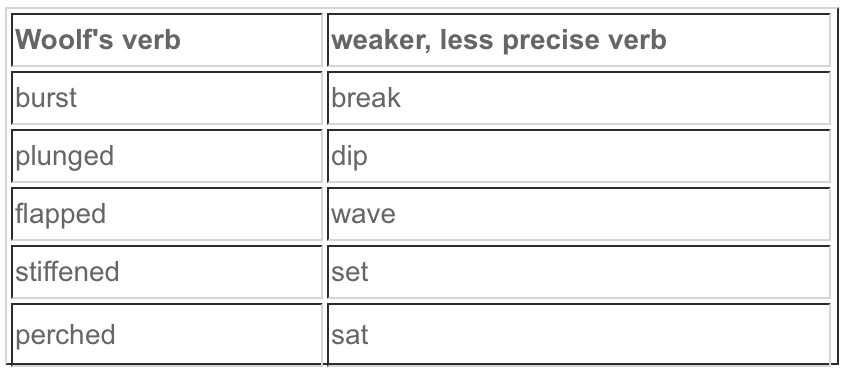

3. Stop Hedging and “Eliminate Weasel Words”

Amazon's third tip for writing for employees is “Eliminate Weasel Words,” and that advice applies to verbs too.

Instead of “nearly all customers,” say, “89 percent of customers.”

Instead of “significantly better,” say, “a 43 percent improvement.”

Weasel words are a form of hedging.

Hedging allows you to avoid commitment by using qualifiers such as “probably,” “maybe,” “sometimes,” “often,” “nearly always,” “I think,” “It seems,” and so on.

Hedge words or phrases soften the impact of a statement or to reduce the level of commitment to the statement's accuracy.

By eliminating hedging, you're forced to strengthen all your language, including verbs.

What do you really think about something? Don't say, “I think.” Stand by it. A thing is or isn't. You don't think it is or believe it is. You stand by it.

If you write courageously with strength of opinion, your verbs grow stronger as well.

Beware the Thesaurus: Strong Verbs are Simple Verbs

I caveat this advice with the advice to beware thesauruses.

Strong writing is almost always simple writing. Compelling action verbs don't have to be obscure–they are precise.

Writers who replace verbs like “was” and “get” with long, five-syllable verbs that mean the same thing as a simple, one-syllable verb don't actually communicate more clearly.

To prepare for this article, I studied the verb use in the first chapters of several books by my favorite authors, including Ernest Hemingway's For Whom the Bell Tolls and Naomi Novik's Deadly Education.

Hemingway has a bigger reputation as a stylist and a “great” writer, but I found that Novik's verb choice was just as strong and even slightly more varied.

Hemingway tended to use simpler, shorter verbs, though, often repeating verbs, whereas Novik's verbs were longer and often more varied.

I love both of these writers, but if you're measuring strength, simplicity will most often win.

In dialogue this is especially important . Writers sometimes try to find every synonym for the word, “said” to describe the exact timber and attitude of how a character is speaking.

This becomes a distraction from the dialogue itself. In dialogue, the words spoken should speak for themselves, not whatever synonym the writer has looked up for “said.”

Writers should use simple speaker tags like “said” and “asked” as a rule, only varying that occasionally when the situation warrants it.

270+ Strong Verbs List

We've argued strong verbs are detailed, descriptive, action verbs, and below, I list over 200 strong verbs to make your writing better.

I compiled this list directly from the first chapters of some of my favorite books, already mentioned previously, For Whom the Bell Tolls by Ernest Hemingway, Deadly Education by Naomi Novik, and The Undoing Project by Michael Lewis.

This is a necessarily simplified list, taken only from the first chapters of those books. There are thousands of strong verbs, usually action verbs, but these are a good start.

I've also sorted them alphabetically and put them into present tense.

- Collaborate

- Intellectualize

The Best Way to Learn to Use Strong Verbs

The above tips will help get you started using strong verbs, but the best way to learn how to grow as a writer with your verbs is through reading.

But not just reading, studying the work of your favorite writers carefully and then trying to emulate it, especially in the genre you write in.

As Cormac McCarthy, who passed away recently, said, “The unfortunate truth is that books are made from books.”

If you want to grow as a writer, start with the books you love. Then adapt your style from there.

Which tip will help you use more strong verbs in your writing today? Let me know in the comments.

Choose one of the following three practice exercises:

1. Study the verb use in the first chapter of one of your favorite books. Write down all of the verbs the author uses. Roughly what percentage are action verbs versus linking verbs? What else do you notice about their verb choice?

2. Free write for fifteen minutes using only action verbs and avoiding all “to be” verbs and adverbs.

3. Edit a piece that you've written, replacing the majority of linking verbs with action verbs and adverbs with stronger verbs.

Share your practice in the Pro Practice Workshop here , and give feedback to a few other writers.

Joe Bunting

Joe Bunting is an author and the leader of The Write Practice community. He is also the author of the new book Crowdsourcing Paris , a real life adventure story set in France. It was a #1 New Release on Amazon. Follow him on Instagram (@jhbunting).

Want best-seller coaching? Book Joe here.

Work with Joe Bunting?

WSJ Bestselling author, founder of The Write Practice, and book coach with 14+ years experience. Joe Bunting specializes in working with Action, Adventure, Fantasy, Historical Fiction, How To, Literary Fiction, Memoir, Mystery, Nonfiction, Science Fiction, and Self Help books. Sound like a good fit for you?

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Submit Comment

Join over 450,000 readers who are saying YES to practice. You’ll also get a free copy of our eBook 14 Prompts :

Popular Resources

Best Resources for Writers Book Writing Tips & Guides Creativity & Inspiration Tips Writing Prompts Grammar & Vocab Resources Best Book Writing Software ProWritingAid Review Writing Teacher Resources Publisher Rocket Review Scrivener Review Gifts for Writers

Books By Our Writers

You've got it! Just us where to send your guide.

Enter your email to get our free 10-step guide to becoming a writer.

You've got it! Just us where to send your book.

Enter your first name and email to get our free book, 14 Prompts.

Want to Get Published?

Enter your email to get our free interactive checklist to writing and publishing a book.

- Resources ›

- For Students and Parents ›

- Homework Help ›

- Study Methods ›

Powerful Verbs for Your Writing

Inventory Your Own Verbs for Powerful Writing

- Study Methods

- Homework Tips

- Learning Styles & Skills

- Time Management

- Private School

- College Admissions

- College Life

- Graduate School

- Business School

- Distance Learning

- M.Ed., Education Administration, University of Georgia

- B.A., History, Armstrong State University

Verbs are action words, right? We all remember that from elementary school. Verbs describe the action that is taking place.

But verbs don't have to surrender all the fun and emotional power to adjectives —the words that traditionally paint the pictures in our heads. As a matter of fact, the most powerful writers use verbs quite effectively to illustrate their writing.

Review Your Verbs

After you complete a draft of your paper, it might be a good idea to conduct a verb inventory. Just read over your draft and underline all your verbs. Do you see repetition? Are you bored?

Verbs like said, walked, looked, and thought can be replaced with more descriptive words like mumbled, sauntered, eyeballed, and pondered . Here are a few more suggestions:

- severed (with his eyes)

Get Creative With Verbs

One way to make verbs more interesting is to invent them from other word forms. Sounds illegal, doesn't it? But it's not like you're printing dollar bills in your basement.

One type of noun that works well is animal types, since some animals have very strong characteristics. Skunks, for instance, have a reputation for being stinky or spoiling the air.

Do the following statements evoke powerful images?

- He skunked the party up with his cologne... She snaked the hallways... She wormed her way out of the class...

Jobs as Verbs

Another noun type that works well is names of occupations. We often use doctor as a verb, as in the following sentence:

- She doctored the paper until it was perfect.

Doesn't that evoke the image of a woman hovering over a piece of writing, tools in hand, crafting and nurturing the paper to perfection? What other occupations could paint such a clear scene? How about police ?

- Mrs. Parsons policed her garden until it was completely pest free.

You can get very creative with unusual verbs:

- bubble-wrapped the insult (to suggest that the insult was surrounded by "softer" words)

- tabled your idea

But you do have to use colorful verbs tactfully. Use good judgment and don't overdo the creativity. Language is like clothing--too much color can be just plain odd.

List of Power Verbs

- How to Write a Diamante Poem

- How to Write a Limerick

- Characteristics of Left Brain Dominant Students

- 5 Tips to Improve Reading Comprehension

- The Kinesthetic Learning Style: Traits and Study Strategies

- How to Study With Flashcards

- Top 17 Exposures to Learn New Words

- What Are the Parts of a Short Story? (How to Write Them)

- How to Remember Dates for a Test - Memorization

- Sentence Problems

- How to Study History Terms

- Great Solutions for 5 Bad Study Habits

- Tips to Improve Your Spelling

- How to Remember What You Read

- How to Alphabetize a List of Words

- 3 Steps to Ace Your Next Test

COMMENTS

The point is that good writing is more about well-chosen nouns and powerful verbs than it is about adjectives and adverbs, regardless what you were told as a kid. There’s no quicker win for you and your manuscript than ferreting out and eliminating flabby verbs and replacing them with vibrant ones.

Improve your essays with these 50 useful verbs for analysis. This list is great for English learners and college students!

Powerful Verbs for Weaving Ideas in Essays. The following verbs are helpful as a means of showing how an example or quote in literature Supports an idea or interpretation. Example + Verb + Explanation or Significance (CD) (CM)

Powerful Verbs for Weaving Ideas in Essays. The following verbs are helpful as a means of showing how an example or quote in literature Supports an idea or interpretation. Example + Verb + Explanation or Significance (CD) (CM)

The following are examples of power verbs that are useful in academic writing, both for supporting an argument and for allowing you to vary the language you use. Power Verbs for Analysis: appraise, define, diagnose, examine, explore, identify, interpret, investigate, observe.

1. In order to. Usage: “In order to” can be used to introduce an explanation for the purpose of an argument. Example: “In order to understand X, we need first to understand Y.” 2. In other words.

Ambiguous verbs dilute writing and poetry. Strong verbs invigorate narrative, and deliver precise meanings without increasing word count. #Words #WritingTips.

In this post, you'll learn the three best techniques to find weak verbs in your writing and replace them with strong ones. We'll also look at a list of the strongest verbs for each type of writing, including the strongest verbs to use.

Verbs like analyze, compare, discuss, explain, make an argument, propose a solution, trace , or research can help you understand what you’re being asked to do with an assignment.

Verbs describe the action that is taking place. But verbs don't have to surrender all the fun and emotional power to adjectives —the words that traditionally paint the pictures in our heads. As a matter of fact, the most powerful writers use verbs quite effectively to illustrate their writing.