An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Belitung Nurs J

- v.8(4); 2022

- PMC10401366

Online ‘chatting’ interviews: An acceptable method for qualitative data collection

Joko gunawan.

1 Faculty of Nursing, Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok, Thailand

2 Belitung Raya Foundation, Manggar, East Belitung, Bangka Belitung, Indonesia

Colleen Marzilli

3 The University of Texas at Tyler, School of Nursing, 3900 University Blvd., Tyler, TX 75799, USA

Yupin Aungsuroch

Associated data.

Not applicable.

Qualitative research methods allow researchers to understand the experiences of patients, nurses, and other healthcare professionals. Qualitative research also provides scientists with information about how decisions are made and the aspects of existing interventions. However, to get to obtain this important information, qualitative research requires holistic, rich, and nuanced data that can be analyzed to determine themes, categories, or emerging patterns. Generally, offline or in-person interviews, focus group discussions, and observations are three core approaches to data collection. However, geographical barriers, logistic challenges, and emergency conditions, such as the COVID-19 pandemic have necessitated the utilization of online interviews, including chatting as an alternative way of collecting data. This editorial aims to discuss the possibility of online chat interviews as an acceptable design in qualitative data collection.

Data collection is the process of gathering information on variables of interest using accurate, authentic, systematic, and appropriate techniques to answer research questions, hypotheses, and desired outcomes. Rigorous data collection is essential to maintaining research integrity and scientific validity of study results (Barrett & Twycross, 2018 ).

Data collection methods are divided into two methods, namely secondary and primary data collection methods. Secondary data is from secondary sources, or sources not compiled directly by the researchers. The data may include published and unpublished works based on research that relies on primary sources (Rabianski, 2003 ). The secondary data collection method does not take long, and the resources of effort and cost are less. Secondary data is now growing as a preferred source of data for researchers due to the movement of open data science and the emergence of Open Access Initiatives (OAI). Along with open data and OAI, the accompanying policies that promote open access are an opportunity for researchers to gain access to data that may have been difficult to obtain in the past.

In contrast, primary data is real-time data, or first-hand obtained directly by researchers. This usually requires significant time, effort, and cost (Rabianski, 2003 ). Primary data collection methods are generally divided into quantitative and qualitative data. The quantitative data is based on mathematical calculations in various formats including inferential and descriptive statistics. The data is usually returned using a questionnaire with closed questions, which are then analyzed using the methods of correlation, regression, prediction, mean, mode, median, and other statistical methods. The other source of primary data is qualitative data, and with this type of data, mathematical calculations are not involved. Data analysis is obtained through words, sounds, feelings, emotions, body language, colors, and other elements that cannot be counted. Qualitative data collection is usually collected using interviews, focus group discussions, and observations which are the core approaches to this type of data collection (Barrett & Twycross, 2018 ). There are many reasons why a researcher may need quantitative or qualitative data, and this depends on the nature of the research, the concept and phenomena of interest, and the study objectives and hypothesis. Therefore, we do not need to argue if quantitative or qualitative data, secondary or primary data collection is best.

This editorial specifically discusses collecting qualitative data using the online “chatting” method. It should be noted that texting and chatting are often used interchangeably. However, there is a slight difference between the two terms. As nouns, “text” consists of various characters, glyphs, symbols, and sentences, but “chat” is an uncountable informal conversation (Wikidiff, n.d. ). As verbs, “text” is sending a text message using either a short message service (SMS) or a multimedia messaging service (MMS) between two or more users via a cellular network or internet connection using mobile devices, laptops, and other compatible computers (Wikidiff, n.d. ). While “chat” is engagement in an informal conversation, or to talk lightly and casually, discuss in an easy and familiar manner, or exchange messages (Free Dictionary, 2022 ). Texting is part of the chatting itself (Wikidiff, n.d. ). In other words, online chatting is defined as an informal conversation over the Internet that offers real-time transmission from the sender to the recipient. Chat messages are usually short so that the recipient responds quickly and is involved in the conversation (Wikipedia, 2022 ). In addition, chatting and instant messaging (IM) are similar, especially when using WhatsApp, Line, Messenger, or other apps. For the sake of consistency, chatting is used in this editorial.

Conversely, it should also be noted that the literature on online chatting as a qualitative data collection method is scarce and creates many contradictions because it is rarely used. Therefore, its validity and reliability are also often questioned. However, validity and reliability are not compromised when using chats for data collection, but the rationale for this method should be reasonable and justifiable. The following are reasons that can be used as references or strengths for the chatting method.

First, during the COVID-19 pandemic, the authors learned that it is tough to collect quantitative and qualitative research data, especially in social science, behavioral science, nursing science, or other disciplines related to humans. Face-to-face interviews are not possible because of the COVID-19 restrictions. This first point reflects that researchers cannot force the use of the typical data collection methods, such as face-to-face, focus groups, and direct observation. Instead, online chat interviews, or chatting, may be used as an alternative way of collecting data. It is not impossible that researchers may face situations like this pandemic again in the future, and that researchers have already prepared another way for data collection through chatting.

Second, in addition to the pandemic or emergency conditions, this chatting method is applicable for multi-settings research design. For example, it is common today to find studies conducted in various regions or comparisons in multiple countries, although they are constrained by geographical conditions. With the technology that supports internet-based chatting, researchers do not need to visit the research setting, which saves time and money (Stieger & Göritz, 2006 ). This provides a convenient option for researchers that eliminates barriers that create difficulties when collecting data from multiple sites across the globe.

Third, there is an argument about the use of telephone or online interviews instead of chatting. To answer this, the authors must first differentiate between telephone and online interviews. Telephone and online interviews are slightly different. Telephone/phone interviews are often conducted without being online, where researchers directly call, or voice-call research respondents through the contact number of the telephone device and mobile phone, or smartphone. Online interviews include (i) telephone/phone online interviews using voice-call features, (ii) video interviews using Zoom, Facetime, Skype, video conferencing, or other video apps, (iii) chat interviews using chat or messenger apps, and (iv) email texting. This online interview may be done formally and informally. However, email texting may not reflect a real-time conversation and take more time (Dowling, 2012 ). It is important to consider why researchers should use chatting instead of video or telephone interviews, and this is related to who and where, or the interview setting.

Who . Suppose researchers collect data on today’s young people, or Gen Z or the internet generation. In that case, the research participants may prefer to use online interviews, especially chatting, such as using Facebook messenger, WhatsApp, Instagram, Line, WeChat, KakaoTalk, and other apps. This is to reduce the formality of the interview itself, which sometimes makes respondents afraid, reluctant, or uncomfortable to answer questions in a formal manner. Researchers will rationally choose a method that makes participants feel comfortable and free to express their ideas and perspectives without limits.

The next element to consider is, why would the researchers prefer chatting over video interviews? Based on the authors’ experience in data collection, some respondents felt embarrassed to show their faces in front of the camera, were unconfident, and made the interview environment uncomfortable (Gunawan et al., 2022 ). Chatting was selected as a data collection technique to promote ease amongst participants. Researchers must also consider the needs and the conditions of the participants. If the participants have physical deficiencies, such as deafness, then it is not possible to conduct telephone or video interviews. Likewise, if the respondent is blind, chatting is not applicable.

Where . This is related to what applications are used, which is in accordance with the location of the target participants. For example, if the research participants are based in Indonesia, using WhatsApp is preferable (Gunawan et al., 2022 ). As of June 23, 2022, 148 million people in Indonesia use WhatsApp (Rizaty, 2022 ). WhatsApp has features for phone calls, video calls, chats, and voice delivery. Two studies (Gunawan et al., 2022 ; Gunawan et al., 2021 ) used WhatsApp in data collection, and the respondents were happy to answer questions using chat and voice recordings. However, in China, using WeChat is preferable for data retrieval (Weil et al., 2020 ). Both WhatsApp and WeChat have multiple features that enable options for various data collections in the form of words, chats, sounds, voices, videos, and even attached documents.

Fourth, repeated interviews are also an important factor to consider for chatting. It is not impossible that interviews need to be repeated after the initial analysis of the data. However, this often presents difficulties because it takes time to reschedule face-to-face or online phone/video interviews. Therefore, chatting is a practical and convenient solution to this problem, either to explore more data or to clarify the statements from the respondents. Based on Gunawan et al. ( 2022 ) related to research on COVID-19 vaccination, if there are two different statements from two research participants, a clarification is needed. For example, in a statement of “it is mandatory to bring a vaccine certificate to make a driver’s license,” one participant said yes, and the other said no. A confirmation is necessary between the two. As a result, the statement was clarified, “For those who want to make a driver’s license, people who have been vaccinated would be prioritized over people who have not; but, that does not mean they are not served, only the process is slowed down” (Gunawan et al., 2022 ). Chatting is an opportunity to clarify with less challenges.

Fifth, the practicality and validity of the chatting data collection method are noted. Chatting is more practical than telephone/video interviews. For example, when researchers conduct telephone/video interviews, audio or video are recorded, followed by verbatim transcription before data analysis, and this process is lengthy. Bryman ( 2012 ) said that transcribing a one-hour interview takes five to six hours and is costly. While in the online chatting method, all conversations, chats, voices, and attached documents are recorded automatically in the mobile app. Researchers can access the stored archive and re-read the content. Chatting facilitates efficient use of time wherein the researchers do not transcribe verbatim or use additional staff resources to transcribe the interviews. Validity of the data is essential for the researcher, and both chatting and telephone/video interviews require a significant amount of coding amongst the various data sources, but the contents and substances between both are not different (Saarijärvi & Bratt, 2021 ). The interviewers’ skills are needed to ask questions and receive answers according to the study purposes.

Additionally, although chatting can be considered an acceptable method for qualitative data collection, it has a weakness. For example, if the research topic or subject under study requires an in-depth interpretation technique where voice’ intonation, rhythm, and volume (emotional tone), as well as body language, are necessary, then chatting is limited and may be inappropriate. However, regardless of the advantages and disadvantages of the chatting method, researchers must control the quality of the data, and this should be addressed for each individual measurement, personal observation, and the entire data set according to the aims of the study.

There are two summary points in this editorial. First, the use of the online chatting method is acceptable if the conditions for video/online interviews are not possible or desirable, either due to limited conditions in the research settings or the study subjects. Second, using chatting as an additional data collection method is suitable if it makes sense and can be accounted. The data collected from different sources in a single study may provide trustworthy findings. However, researchers cannot impose one method for data collection. Freedom and flexibility are needed to gain more understanding of the phenomenon in order to obtain holistic, rich, and nuanced data.

Acknowledgment

Declaration of conflicting interest.

The author declares that they have no conflict of interest in this study.

Second Century Fund (C2F), Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok, Thailand.

Authors’ Contributions

All authors contributed equally in this article.

Authors’ Biographies

Joko Gunawan, S.Kep.Ners, PhD is Managing Editor of Belitung Nursing Journal. He is also Postdoctoral Researcher at the Faculty of Nursing, Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok, Thailand.

Colleen Marzilli, PhD, DNP, MBA, RN-BC, CCM, PHNA-BC, CNE, NEA-BC, FNAP is Associate Professor at the University of Texas at Tyler, USA. She is also on the Editorial Advisory Board of Belitung Nursing Journal.

Yupin Aungsuroch, PhD, RN is Associate Professor at the Faculty of Nursing, Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok, Thailand. She is also an Editor-in-Chief of Belitung Nursing Journal.

Data Availability

Ethical consideration.

- Barrett, D., & Twycross, A. (2018). Data collection in qualitative research . Evidence Based Nursing , 21 ( 3 ), 63-64. 10.1136/eb-2018-102939 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bryman, A. (2012). Social research methods (4th ed.). Oxford: Oxford university press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Dowling, S. (2012). Online asynchronous and face-to-face interviewing: Comparing methods for exploring women’s experiences of breastfeeding long term . Cases in Online Interview Research , 277-296. 10.4135/9781506335155.n11 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Free Dictionary . (2022). Chat . https://www.thefreedictionary.com/chatting

- Gunawan, J., Aungsuroch, Y., Fisher, M. L., Marzilli, C., & Sukarna, A. (2022). Identifying and understanding challenges to inform new approaches to improve vaccination rates: A qualitative study in Indonesia . Journal of Nursing Scholarship . 10.1111/jnu.12793 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gunawan, J., Aungsuroch, Y., Marzilli, C., Fisher, M. L., & Sukarna, A. (2021). A phenomenological study of the lived experience of nurses in the battle of COVID-19 . Nursing Outlook , 69 ( 4 ), 652-659. 10.1016/j.outlook.2021.01.020 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Rabianski, J. S. (2003). Primary and secondary data: Concepts, concerns, errors, and issues . The Appraisal Journal , 71 ( 1 ), 43-55. [ Google Scholar ]

- Rizaty, M. A. (2022). WhatsApp global users touch 2.2 billion figures until first quarter 2022 [in Bahasa] . https://databoks.katadata.co.id/datapublish/2022/06/23/pengguna-whatsapp-global-sentuh-angka-22-miliar-hingga-kuartal-i-2022

- Saarijärvi, M., & Bratt, E.-L. (2021). When face-to-face interviews are not possible: Tips and tricks for video, telephone, online chat, and email interviews in qualitative research . European Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing , 20 ( 4 ), 392-396. 10.1093/eurjcn/zvab038 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Stieger, S., & Göritz, A. (2006). Using Instant Messaging for Internet-based interviews . Cyberpsychology & Behavior , 9 , 552-559. 10.1089/cpb.2006.9.552 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Weil, J., Karlin, N., & Lyu, Z. (2020). Mobile messenger apps as data-collection method among older adults: WeChat in a health-related survey in the People’s Republic of China . SAGE Publication. 10.4135/9781529707755 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Wikidiff . (n.d.). Texting vs chatting - What's the difference? https://wikidiff.com/chatting/texting

- Wikipedia . (2022). Online chat . https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Online_chat

- Search Menu

Sign in through your institution

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Numismatics

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Social History

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Acquisition

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Media

- Music and Religion

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Legal System - Costs and Funding

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Restitution

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Ethics

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Ethics

- Business Strategy

- Business History

- Business and Technology

- Business and Government

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Social Issues in Business and Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic History

- Economic Systems

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Social Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Sustainability

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- Ethnic Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Theory

- Politics and Law

- Politics of Development

- Public Policy

- Public Administration

- Qualitative Political Methodology

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Disability Studies

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

12 The Social Consequences of Online Interaction

Jenna L. Clark, Center for Advanced Hindsight at Duke University

Melanie C. Green, University at Buffalo

- Published: 10 September 2018

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

This chapter provides an overview of the social consequences of online interaction. Research has provided mixed evidence about whether online interaction is helpful or harmful for well-being and social connectedness. This chapter highlights the factors that moderate the influence of online social interaction on outcomes, with a particular focus on user behaviors. The Interpersonal Connection Behaviors Framework suggests that the positive consequences of any given online interaction depend on the extent to which that interaction serves a relational purpose. Online interactions that promote connection build relationships and increase well-being via increased relational closeness and quality through processes such as self-disclosure and social support. Online interactions that do not promote connection are likely to fall prey to disadvantages like social comparison or loneliness.

Personal account

- Sign in with email/username & password

- Get email alerts

- Save searches

- Purchase content

- Activate your purchase/trial code

- Add your ORCID iD

Institutional access

Sign in with a library card.

- Sign in with username/password

- Recommend to your librarian

- Institutional account management

- Get help with access

Access to content on Oxford Academic is often provided through institutional subscriptions and purchases. If you are a member of an institution with an active account, you may be able to access content in one of the following ways:

IP based access

Typically, access is provided across an institutional network to a range of IP addresses. This authentication occurs automatically, and it is not possible to sign out of an IP authenticated account.

Choose this option to get remote access when outside your institution. Shibboleth/Open Athens technology is used to provide single sign-on between your institution’s website and Oxford Academic.

- Click Sign in through your institution.

- Select your institution from the list provided, which will take you to your institution's website to sign in.

- When on the institution site, please use the credentials provided by your institution. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

- Following successful sign in, you will be returned to Oxford Academic.

If your institution is not listed or you cannot sign in to your institution’s website, please contact your librarian or administrator.

Enter your library card number to sign in. If you cannot sign in, please contact your librarian.

Society Members

Society member access to a journal is achieved in one of the following ways:

Sign in through society site

Many societies offer single sign-on between the society website and Oxford Academic. If you see ‘Sign in through society site’ in the sign in pane within a journal:

- Click Sign in through society site.

- When on the society site, please use the credentials provided by that society. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

If you do not have a society account or have forgotten your username or password, please contact your society.

Sign in using a personal account

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members. See below.

A personal account can be used to get email alerts, save searches, purchase content, and activate subscriptions.

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members.

Viewing your signed in accounts

Click the account icon in the top right to:

- View your signed in personal account and access account management features.

- View the institutional accounts that are providing access.

Signed in but can't access content

Oxford Academic is home to a wide variety of products. The institutional subscription may not cover the content that you are trying to access. If you believe you should have access to that content, please contact your librarian.

For librarians and administrators, your personal account also provides access to institutional account management. Here you will find options to view and activate subscriptions, manage institutional settings and access options, access usage statistics, and more.

Our books are available by subscription or purchase to libraries and institutions.

| Month: | Total Views: |

|---|---|

| October 2022 | 7 |

| November 2022 | 10 |

| December 2022 | 8 |

| January 2023 | 16 |

| February 2023 | 23 |

| March 2023 | 13 |

| April 2023 | 14 |

| May 2023 | 16 |

| June 2023 | 5 |

| July 2023 | 12 |

| August 2023 | 3 |

| September 2023 | 9 |

| October 2023 | 19 |

| November 2023 | 11 |

| December 2023 | 8 |

| January 2024 | 1 |

| February 2024 | 50 |

| March 2024 | 28 |

| April 2024 | 10 |

| May 2024 | 23 |

| June 2024 | 14 |

| July 2024 | 7 |

| August 2024 | 4 |

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Rights and permissions

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 10 May 2012

Emotional persistence in online chatting communities

- Antonios Garas 1 ,

- David Garcia 1 ,

- Marcin Skowron 2 &

- Frank Schweitzer 1

Scientific Reports volume 2 , Article number: 402 ( 2012 ) Cite this article

11k Accesses

85 Citations

47 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Applied physics

- Statistical physics, thermodynamics and nonlinear dynamics

- Theoretical physics

How do users behave in online chatrooms, where they instantaneously read and write posts? We analyzed about 2.5 million posts covering various topics in Internet relay channels and found that user activity patterns follow known power-law and stretched exponential distributions, indicating that online chat activity is not different from other forms of communication. Analysing the emotional expressions (positive, negative, neutral) of users, we revealed a remarkable persistence both for individual users and channels. I.e. despite their anonymity, users tend to follow social norms in repeated interactions in online chats, which results in a specific emotional “tone” of the channels. We provide an agent-based model of emotional interaction, which recovers qualitatively both the activity patterns in chatrooms and the emotional persistence of users and channels. While our assumptions about agent's emotional expressions are rooted in psychology, the model allows to test different hypothesis regarding their emotional impact in online communication.

Similar content being viewed by others

Risk and prosocial behavioural cues elicit human-like response patterns from AI chatbots

Affective polarization and dynamics of information spread in online networks

Dynamics of online hate and misinformation

Introduction.

How do human communication patterns change on the Internet? Round the clock activities of Internet users put us into the comfortable situation of having massive data from various sources available at a fine time resolution. But what to look at? Which aggregated measures are most appropriate to capture how new technologies affect our communicative behavior? And then, are we able to match these findings with a dynamic model that is able to generate insights into their origin? In this paper, we provide both: a new way of analysing data from online chats and a model of interacting agents to reproduce the stylized facts of our analysis. In addition to the activity patterns of users, we also analyse and model their emotional expressions that trigger the interactions of users in online chats. Validating our agent-based model against empirical findings allows us to draw conclusions about the role of emotions in this form of communication.

Online communication can be seen as a large-scale social experiment that constantly provides us with data about user activities and interactions. Consequently, time series analyses have already revealed remarkable temporal activity patterns, e.g. in email communication. Such patterns allow conclusions how humans organize their time and give different priorities to their communication tasks 1 , 2 , 3 , 5 , 6 , 7 . One particular quantity to describe these patterns is the distribution P (τ) of the waiting time τ that elapses before a particular user answers e.g. an email. Different studies have confirmed the power-law nature of this distribution, P (τ) ~ τ −α . Its origin was attributed either to the burstiness of events 2 or to circadian activity patterns 3 , while a recent work shows that a combination of both effects is also a plausible scenario 4 . However, the value of the exponent α is still debated. A stochastic priority queue model 6 allows to derive α by comparing two different rates, the average rate λ of messages arriving and the average rate µ of processing messages. If µ ≤ λ, i.e. if messages arrive faster than they can be processed, α = 3/2 was found, which is compatible with most empirical findings and simulation models 1 , 2 , 3 , 8 . However, in the opposite case, µ ≥ λ, i.e. if messages can be processed upon arrival, α = 5/2 was found together with an exponential correction term. The latter regime, also denoted as the “highly attentive regime”, could be verified empirically so far only by using data about donations 7 . So, it is an interesting question to analyze other forms of online communication to see whether there is evidence for the second regime.

In this paper, we analyze data about instant online communication in different chatting communities, specifically Internet Relay Chat (IRC) channels, where each channel covers a particular topic. Prior to the very common social networking sites of today, IRC channels provided a safe and independent way for users to share and discuss information outside traditional media. Different from other types of online communication, such as blogs or fora where entries are posted at a given time (decided by the writer), IRC chats are instantaneous in real time, i.e. users read while the post is written and can react immediately. This type of interaction requires much higher user activity in comparison to persistent communication e.g. in fora. Further, it is more spontaneous, often leading to emotionally-rich communication between involved peers. Consequently, instant communication should require specific tools and models for analysis, that are capable of covering these predominant features.

Nowadays, IRC channels are still one of the most used platforms for collective real-time online communication and are used for various purposes, e.g. organization of open-source project development, Internet activism, dating, etc. Our dataset (described in detail in the data section), consists of 20 IRC channels covering topics as diverse as music, sports, casuals chats, business, politics, or computer related issues – which is important to ensure that there is no topical bias involved in our analysis. For each channel, we have consecutive daily recordings of the open discussion over a period of 42 days, which amounts to more than 2.5 million posts in total generated by more than 20.000 different users.

We process our analysis as follows: first, we look into the communication patterns of instant online discussions, to find out about the average response time of users and its possible dependence on the topics discussed. This shall allow us to identify differences between instantaneous chatting communities and other forms of slower, persistent communication. In a second step, we look more closely into the content of the discussions and how they depend on the emotions expressed by users. Remarkably, we find that most users are very persistent in expressing their positive or negative emotions - which is not expected given the variety of topics and the user anonymity. This leads us to the question in what respect online chats are different from offline discussions which are mostly guided by social norms. We argue that even in instantaneous, anonymous online chats users behave very much like “normal” people. Our quantitative insights into user's activity patters and their emotional expressions are eventually combined to model interacting emotional agents. We demonstrate that the stylised facts of the emotional persistence can be reproduced by our model by only calibrating a small set of agent features. This success indicates that our modeling framework can be used to test further hypothesis about emotional interaction in online communities.

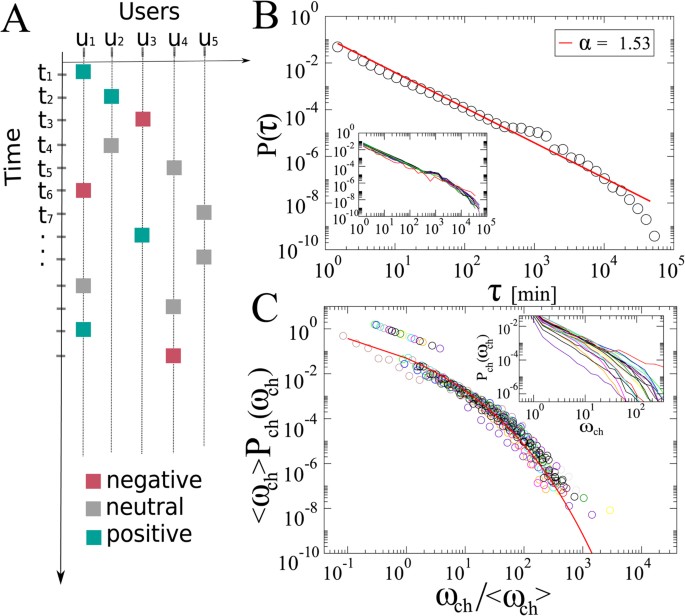

User activity patterns

An IRC channel is always active and enables the real time exchange of posts among users about a specific topic. User interaction is instantaneous, the post written by user u 1 is immediately visible to all other users logged into this channel and user u 2 may reply right away. Fig. 1 illustrates the dynamics in such a channel. As time evolves new users may enter, others may leave or stay quiet until they write follow-up posts at a later time.

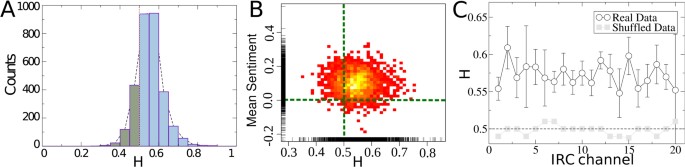

Communication activity over an IRC channel.

A) Schema of the evolution of a conversation in an IRC channel. At every time step, a user enters a post expressing a positive, negative, or neutral emotion. B) Probability distribution of the user activity over all the IRC channels. The activity is expressed as the time interval τ between two consecutive posts of the same user. Inset: Probability distribution of the user activity for individual IRC channels. The time is measured in minutes. C) Scaled probability distribution of the time interval ω ch between consecutive posts entered in all the 20 IRC channels. The solid line represents stretched exponential fit to the data. Inset: Probability distribution of the time interval ω ch between consecutive posts entered in all the 20 IRC channels without rescaling. The time is measured in minutes.

To characterize these activity patterns, we analyzed the waiting-time, or inter-activity time distribution P (τ), where τ refers to the time interval between two consecutive posts of the same user in the same channel and ask about the average response time. We find that τ is power-law distributed P (τ) ~ τ −α with some cut-off ( Fig. 1B ), with an exponent α = 1.53 ± 0.02. The fit is based on the maximum likelihood approach proposed by Clauset et al. 9 and the power-law nature of the distribution could not be rejected ( p = 0.375).

This finding (a) is inline the power-law distribution already found for diverse human activities 1 , 2 , 3 , 5 , 6 , 7 and (b) classifies the communication process as belonging to the regime where posts arrive faster than they can be processed. We note that for α < 2, no average response time is defined (which would have been the case, however, for the highly attentive regime). Further, we observe in the plot of Fig. 1B a slight deviation from the power-law at a time interval of about one day, which shows that some users have an additional regularity in their behavior with respect to the time of the day they enter the online discussion. Such deviations were usually treated as power-laws with an exponential cut-off and can even be explained based on simple entropic arguments 10 , 11 . However, because of the “bump” around the one day time interval, our distribution also seems to provide further evidence to the bi-modality proposed by Wu et al. 12 . We should note, however, that the tail is better fitted by a log-normal distribution (KS = 0.136) rather than an exponential (KS = 0.190) or a Weibull (KS = 0.188) one (again using the maximum likelihood methodology described by Clauset et al. 9 ) as shown in Fig. 1B . Here, KS stands for the Kolmogorov-Smirnov statistical test; the smaller this number, the better the fit.

We now focus on an important difference between online chats and previously studied forms of communication, such as mail or email exchange, which mostly involve two participants. Due to the collective nature of chats, a chatroom automatically aggregates the posts of a much larger amount of users, which allows us to study their collective temporal behavior. If ω denotes the time interval between two consecutive posts in the same channel independent of any user (also denoted as inter-event time and to be distinguished from the inter-activity time characterizing a single user), we find that the distribution P (ω) is is still fat-tailed, but does not follow a power-law. Interestingly, the time interval between posts significantly depends on the topic discussed in the channel (Inset of Fig. 1C ). Some “hot” topics receive posts at a shorter rate than others, which can be traced back to the different number of users involved into these discussions. Specifically, we find that the average inter-event time 〈ω〉 ch depends on the amount of users in the conversation and becomes smaller for more popular channels, as one would expect.

If we rescale the channel dependent inter-event distribution P ch (ω) using the average inter-event time 〈ω〉 ch per channel and plot 〈ω ch 〉 P ch (ω ch ) versus ω ch /〈ω ch 〉, we find that all the curves collapse into one master curve ( Fig. 1C ). The general scaling form that we used is P (ω) = (1/<ω>) F (ω/<ω>), where F(x) is independent of the average activity level of the component and represents a universal characteristic of the particular system. Such scaling behavior was reported previously in the literature describing universal patterns in human activity 13 . We fit this master curve by a stretched exponential 14 , 15 , 16

where the stretched exponent γ is the only fit parameter, while the other two factors a γ and β γ are dependent on γ 14 . A histogram of the γ values across the 20 channels is shown in Supplementary Figure S2 . Using only the regression results with p < 0.001 we find that the mean value of the stretched exponents is 〈γ〉 = 0.21 ± 0.05.

We note that stretched exponentials have been reported to describe the inter-event time distribution in systems as diverse as earthquakes 15 and stock markets 16 . These systems commonly exhibit long range correlations which seem to be the origin of the stretched exponential inter-event time distributions 14 . Long range correlations have also been reported in human interaction activity 5 , 17 and we tested their presence in the temporal activity over IRC communication. As shown in the Supplementary Figure S3 , we verified the existence of long range correlations in the conversation activity. We found that the decay of the autocorrelation function of the inter-event time interval between consecutive posts within a channel is described by a power-law

In conclusion, our analysis of user activities have revealed a universal dynamics in online chatting communities which is moreover similar to other human activities. This regards (a) the temporal activity of individual users (characterized by a power-law distribution with exponent 3/2) and (b) the inter-event dynamics across different channels, if rescaled by the average inter-event time (characterized by a stretched exponential distribution with just one fit parameter). We will use these findings as a point of departure for a more in-depth analysis – because obviously the essence of online communication in chatrooms, as compared to other human activities, is not really covered. From the perspective of activity patters, there is not so much new here, which leads us to ask for other dimensions of human communication that could reveal a difference.

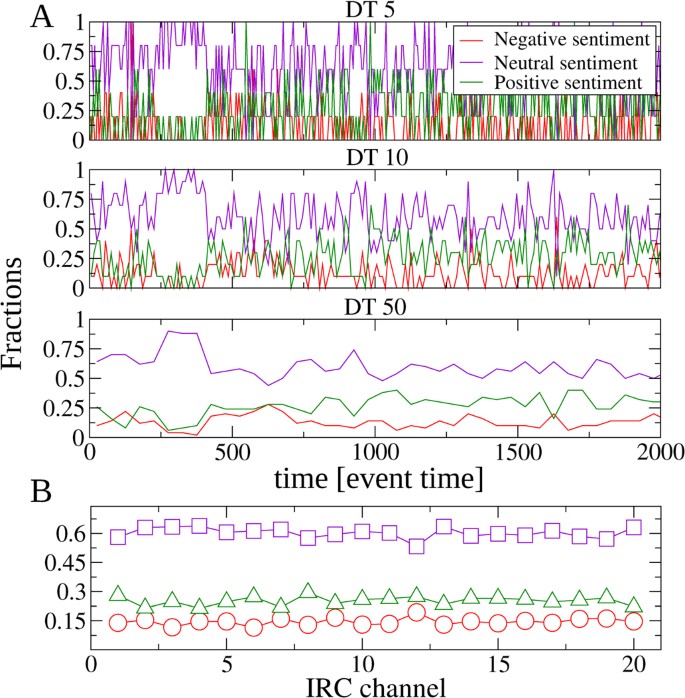

Emotional expression patterns

Human communication, in addition to the mere transmission of information, also serves purposes such as the reinforcement of social bonds. This could be one of the reasons why human languages are found to be biased towards using words with positive emotional charge 20 . Humans, from the early stages of our lives, develop an affective communication system that enables us to express and regulate emotions 21 . But emotions are also the mediators of our consumer responses to advertising 22 and many scientists acknowledge their importance in motivating our cognition and action 23 . However, despite the increasing time we spend online, the way we express our emotions in online communities and its impact on possibly large amounts of people is still to be explored.

Consequently, we are interested in the role of expressed emotions in online chatting communities. Users, by posting text in chatrooms, also reveal their emotions, which in return can influence the emotional response of other users, as illustrated in Fig. 1A . To understand this emotional interaction, we carry out a sentiment analysis of each post which is described in detail in the Methods section. This automatic classification returns the valence v for each post, i.e. a discrete value {−1, 0, +1} that characterizes the emotional charge as either negative, neutral, or positive.

Instead of using the real time stamp of each post as in the analysis of the user activity, we now use an artificial time scale in which at each (discrete) time step one post enters the discussion, so the number of time steps equals the total number of posts. We then monitor how the total emotion expressed in a given channel evolves over time. We use a moving average approach that calculates the mean emotional polarity over different time windows. In Fig. 2A we plot the fraction of neutral, negative and positive posts as a function of time, for different sizes of the time window. While it is obvious that the emotional content largely fluctuates when using a very small time window, we find that for decreasing time resolution (i.e. increasing time window) the fractions of emotional posts settle down to an almost constant value around which they fluctuate. From this, we can make two interesting observations: (i) the emotional content in the online chats does not really change in the long run (one should notice that times of the order 10 3 are still large compared to the time window DT = 50 used), i.e. we observe fluctuations that depend on the time resolution, but no “evolution” towards more positive or negative sentiments. (ii) For the low resolution, the fraction of neutral posts dominates the positive and negative posts at all times. In fact there is a clear ranking where the fraction of negative posts is always the smallest. Both observations become even more pronounced when averaging over the 20 IRC channels, as Fig. 2B shows.

Emotional expressions over different time scales.

A) Fraction of expressions with negative, neutral and positive emotion values under different time scales for one channel. B) Fraction of expressions with negative, neutral and positive emotion values for the 20 IRC channels.

Our findings differ from previous observations of emotional communication in blog posts and forum comments which identified a clear tendency toward negative contributions over time, in particular for periods of intensive user activity 24 , 25 . Such findings suggest that an increased number of negative emotional posts could boost the activity and extend the lifetime of a forum discussion. However, blog communication in general evolves slower than e.g. online chats. Hence, we need to better understand the role of emotions in real time Internet communication, which obviously differs from the persistent and delayed interaction in blogs and fora.

To further approach this goal, we analyse to what extend the rather constant fraction of emotional posts in IRC channels is due to a persistence in the emotional expressions of users. For this, we apply the DFA technique 18 , to the time series of positive, negative and neutral posts. Since our focus is now on the user, we reconstruct for every user a time series that consists of all posts communicated in any channel, where the time stamp is given by the consecutive number at which the post enters the user's record. In order to have reliable statistics, for the further analysis only those users with more than 100 posts are considered (which are nearly 3000 users). As the examples in the Supplementary Figure S4 show, some users are very persistent in their (positive) emotional expressions (even that they occasionally switch to neutral or negative posts), whereas others are really antipersistent in the sense that their expressed emotionality rapidly changes through all three states. The persistence of these users can be characterized by a scalar value, the Hurst exponent H , (see the Material and Methods Section for details) which is 0.5 if users switch randomly between the emotional states, larger than 0.5. if users are rather persistent in their emotional expressions, or smaller than 0.5 if users have strong tendency to switch between opposite states, as the antipersistent time series of Fig. S4 shows.

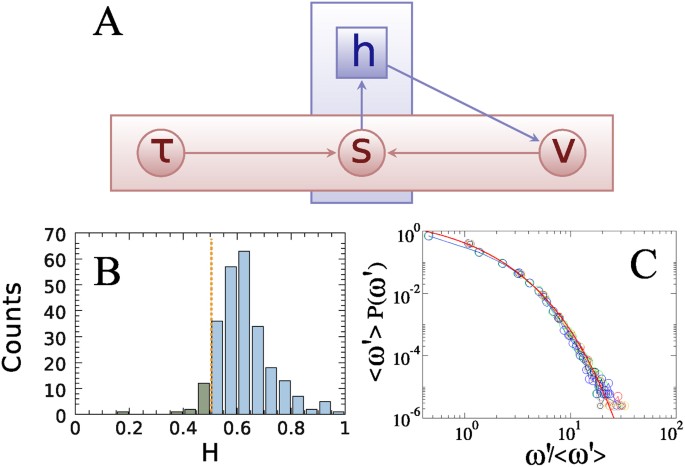

If we analyse the distribution of the Hurst exponents of all users, shown in the histogram of Fig. 3A , we find (a) that the emotional expression of users is far from being random and (b) that it is clearly skewed towards H > 0.5, which means that the majority of users is quite persistent regarding their positive, negative or neutral emotions. This persistence can be also seen as a kind of memory (or inertia) in changing the emotional expression, i.e. the following post from the same user is more likely to have the same emotional value.

Hurst exponents and emotional persistence.

A) Hurst exponents ( H ) of the emotional expression of individual users, obtained using the DFA method. Only users contributed more than 100 posts were considered and we used the exponents obtained with fitting quality R 2 > 0.98. B) Hurst exponent ( H ) versus the mean emotion polarity expressed by individual users, again only from users who contributed more than 100 posts. C) Hurst exponents ( H ) of the emotions expressed in the 20 IRC channels. The values are averages of the Hurst exponents obtained from 10 different segments of the same channel and the error bars show the standard deviation. The horizontal dashed line shows the expected value for random time series ( H = 0.5) and the gray squares show the value obtained from shuffling the real time series to destroy any correlations. The difference in exponents of the real and the shuffled time series is statistically significant with p < 0.001.

The question whether persistent users express more positive or negative emotions is answered in Fig. 3B , where we show a scatter plot of H versus the mean value of the emotions expressed by each user. Again, we verify that the majority of users has H > 0.5, but we also see that the mean value of emotions expressed by the persistent users is largely positive. This corresponds to the general bias towards positive emotional expression detected in written expression 20 . The lower left quadrant of the scatter plot is almost empty, which means that users expressing on average negative emotions tend to be persistent as well. A possible interpretation for this could be the relation between negative personal experiences and rumination as discussed in psychology 26 . Antipersistent users, on the other hand, mostly switch between positive and neutral emotions.

Are the more active users also the emotionally persistent ones? In Supplementary Figure S6 we show a scatter plot of the Hurst exponent dependent on the total activity of each user. Even though the mean value of H does not show any such dependence, we observe large heterogeneity on the values of H for users with low activity. Furthermore, in Supplementary Figure S7 we show that the Hurst exponent of a very active user varies only slightly if we divide his time series into various segments and apply the DFA method to these segments. Thus we can conclude that active users tend to be emotionally persistent and, as most persistent users express positive emotions, they tend to provide some kind of positive bias to the IRC, whereas users occasionally entering the chat may just try to get rid of some negative emotions.

This leads us to the question how persistent the emotional bias of a whole discussion is. While Fig. 3A has shown the persistence with respect to the different users, Fig. 3C plots the persistence for the different channels, which each feature a very different topic. This persistence holds even even if we analyse only certain segments of the channel, as it is shown in Supplementary Figure S8 . So, we conclude that the persistence of the discussion per se (which is different from the persistence of the users which can leave or enter a arbitrary times) reflects a certain narrative memory. Precisely, for each chat, we observe the emergence of a certain (emotional) ”tone” in the narration which can be positive, negative or neutral, dependent the emotional expressions of the (majority of) persistent users. If we reshuffle these time series such that the same total number of positive, negative and neutral posts is kept, but temporal correlations are destroyed, then the persistence is lost as well as Fig. 3C shows. We note that we could not find evidence of correlations using the autocorrelation function of the emotion time series, while the observed persistence in the fluctuations of user emotional expression, as captured by the Hurst exponent is very robust. This indicates that the chat community assumes an emotional memory locally encoded in the current messages (from the user perspective), while the size of the conversation is too large to detect it through averaging techniques.

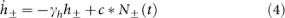

An agent-based model for chatroom users

After identifying both the activity patterns and the emotional expression patterns of users in online chats, we setup an agent-based model that is able to reproduce these stylized facts. We start from a general framework 27 , designed to model and explain the emergence of collective emotions in online communities through the evolution of psychological variables that can be measured in experimental setups and psychological studies 28 , 29 . This framework provides a unified approach to create models that capture collective properties of different online communities and allows to compare the different emotional microdynamics present in various types of communication. The case of IRC channel communication is of particular interest because of its fast and ephemeral nature. Thus, we have designed a model for IRC chatrooms, as shown in Fig. 4A . The agents in our model are characterized by two variables, their emotionality, or valence, v which is either positive or negative and their activity, or arousal, which is represented by the time interval τ between two posts s in the chatroom. The valence of an agent i , represented by the internal variable v i , changes in time due to a superposition of stochastic and deterministic influences 27 , 30 :

The stochastic influences are modeled as a random factor A v ξ i normally distributed with zero mean and amplitude A v and represent all changes of the individual emotional state apart from chat communication. The deterministic influences are composed of an internal decay of parameter γ v and an external influence of the conversation. The change in the valence caused by the emotionality of the field ( h + − h − ) is measured in valence change per time unit through the parameter b . Previous models under the same framework 27 , 31 had an additional saturation term in the equation of the valence dynamics. This way the positive feedback between v and h was limited when the field was very large. But, as we show in Fig. 2 , chatrooms do not show the extreme cases of emotional polarization observed in other communities. Thus, we simplify the dynamics of the valence without using any saturation terms, since a large imbalance between h + and h − is unrealistic given our analysis of real IRC data.

Modeling schema and simulation results.

A) Schematic representation of the model: The horizontal layer represents the agent, the vertical layer the communication in the chatroom where posts are aggregated. After a time lapse τ, which follows the power-law distribution of Fig. 1B , the agents writes a post s which implicitly expresses its emotions, v. Posts read in the chatroom feed back on the emotional state v of the agent. B) Hurst exponents for the individual behavior of agents in isolation with A v ∈ [0.2, 0.5] and γ v ∈ [0.2, 0.5]. Only the exponents derived with fitting quality R 2 > 0.9 are considered. C) Scaled probability distribution of the time interval ω′ between consecutive posts in 10 simulations of the model. Stretched exponential fit shows similar behavior to real IRC channel data.

In general, the level of activity associated with the emotion, known as arousal, can be explicitly modeled by stochastic dynamics as well 31 . Here, the activity of an agent is estimated by the time-delay distribution that triggers the expression of the agent, i.e. by the power-law distribution P (τ) ~ τ −1.53 shown in Fig. 1B . Assuming that an agent becomes active and expresses its emotion at time t , it will become active again after a period τ. The agent then writes a post in the online chat the emotional content of which is determined by its valence (see below). This information is stored in an external field common for all agents, which is composed of two components, h − and h + , for negative and positive information and their difference measures the emotional charge of the communication activity. Since we are interested in emotional communication, we assume that all neutral posts entered, or already present, in a chatroom do not influence the emotions of the agents participating to the conversation. Thus, the dynamics of the field is influenced only by the amount of agents expressing a particular emotion at a given time: N + ( t ) = Σ i (1 − Θ(−1 * s i )) and N − ( t ) = Σ i (1−Θ( s i )), where Θ is the Heaviside step function. Therefore, the time dynamics of the fields can be described as:

These two field components, h + and h − , decay exponentially with a constant factor γ h , i.e. their importance decays very fast as they move further down the screen (posts never disappear, but become less influential). Each field increases by a fixed amount c from every post stored in it. The values of the valence of the agents are changed by the field components, as described by Eq. 3. In contrast with traditional means of communication, online social media can aggregate much larger volumes of user-generated information. This is why h is defined without explicit bounds. Chatrooms pose a special case to this kind of communication, as they can contain large amount of posts but limited amount of users. Most IRC channels have technical limitations for the amount of users that can be connected at once, which in turn is reflected in the total amount of posts present in the general discussion. In our model, h might take any value, but the empirical activity pattern combined with the fixed size of the community dynamically constraints it to limited values.

Whenever an agent creates a new post in an ongoing conversation, the variable, s i , obtain its value in the following way: